Abstract

Stream restorations are a popular, if sometimes controversial, method to clean polluted waterways. We describe a restoration project in a long-ignored portion of a college campus that illustrates the potential for these projects to do more than just remove sediment and nutrients. The project began as a unique collaboration among city government, a university, an ecological restoration company, and a landscape-design firm. Subsequent community engagement established a shared plan for the restored and accessible stream, and then extended the plan to the creation of a multifunctional landscape honoring the ecology and the cultural history of the site. Faculty engagement was central to the process of holding space for multiple visions. Engaging with those upstream as well as downstream, in both space and time, the process invited a healthy level of messiness. With water at the center, this project pushed us toward “resilient practices of emergence” that prioritized relationships and multiple perspectives over ownership.

[Octavia Butler] said, “All that you touch you change / all that you change changes you.” We are constantly impacting and changing our civilization. . . . And we are working to transform a world that is, by its very nature, in a constant state of change.

—Adrienne Maree Brown, “What Is Emergent Strategy?”

Ask any group of students at University of Richmond why they chose UR, and someone will say, “It’s such a beautiful campus!” and every head will nod. The grounds consistently top rankings such as Princeton Review’s Most Beautiful Campuses. The university tour guides will happily share that the picturesque campus was designed by Charles Gillette to be built around Westhampton Lake on the land of a former amusement park, and that it is now listed on the National Register of Historic Places as an archetypal example of Collegiate Gothic architecture. Of course, that’s only part of the story. An ecological stream restoration in a long-ignored portion of campus is helping to daylight both the stream that runs through it and the hidden history that surrounds it (see Fig. 1). We describe how the project has tapped into faculty, student, and community interest and energy to do more than simply remove sediments and nutrients from an unhealthy stream. Using tenets of ecological urbanism (Mostafavi and Doherty 2016), we are actively defining a new hub on campus where conversations about the past, present, and future are occurring around a flowing waterway that embodies the many connections that have come to define the site.

Little Westham Creek runs from the lake at the center of UR’s campus to the nearby James River, with this water eventually emptying into the Chesapeake Bay. The creek has a fraught history, beginning with the horrific displacement of the original Monacan and Powhatan Confederacy custodians of the land and continuing with the deplorable actions of Benjamin Washington Green to utilize the site and its water resources. One hundred eighty years ago, Mr. Green purchased 62 acres of land on the western edge of the City of Richmond and enslaved 15 men, women, and children to operate a grist and sawmill along the creek. In 1914, Richmond College was “gifted” this property as part of a larger venture by wealthy real estate investors to induce the school to move from its downtown location and thus increase neighboring property values following the failure of the amusement park. A hundred years later, the now University of Richmond is grappling with elements of this history, including a legacy of building names tied to racism and the discovery of an on-campus burial ground for enslaved people that worked the land.

Predating any discussion of stream restoration, the university was already recognizing the potential for the space as a significant “recreational greenway” in its Campus Master Plan. The focal point of this greenway was an abandoned road that ran parallel to the stream and was moderately used by the local community as a walking and biking trail. From the city’s perspective, this path had the potential to serve as a missing link to connect several regional bike routes. Local bicycle advocates began a dialogue with the university about how the trail could catalyze multimodal transportation in the area. However, the trail was in serious disrepair. It was washed out in multiple spots and completely overrun with invasive plants. It is into this historical, recreational, and ecological context that a stream restoration was proposed.

When conversations began to broaden to include water quality, the idea of community partnership was already central to our efforts. Following a site visit to talk about opportunities for repaving and landscaping the trail, Waterstreet Studio (a local landscape architecture firm and one of our community partners) suggested meeting with RES (the nation's largest ecological restoration company) to explore a possible stream restoration as part of the City of Richmond’s RVAH2O program. Because water from the stream eventually winds its way into the Chesapeake Bay, Chesapeake Bay Program Stream Restoration Credits could be used to help fund a multimillion dollar face-lift that would include the annual removal of up to 230 tons of sediment, 1,400 pounds of phosphorus, and 3,500 pounds of nitrogen to help clean up the Bay. With heavy equipment being brought in to repair the stream, it provided an opportunity to reimagine the entire space, including the trail and surrounding forests, fields, and infrastructure. Thus, the Eco-Corridor restoration project was officially born. What started with a conversation about resurfacing an old road became an ecological restoration, which in turn led to an exercise in community building to reimagine over 2,000 linear feet of degraded stream within the 19-acre section of campus that included the abandoned road and old mill site (see Fig. 2).

Stream restorations are an increasingly popular approach for municipalities in the region to reach their water quality goals, but they are not without controversy. The partnerships that led to the Eco-Corridor project were built directly on the heels of another proposed stream restoration in Richmond, at Reedy Creek, that was abandoned due at least in part to community resistance. That public struggle left the city feeling wary of projects with weak public buy-in. Embedding this new project within the grounds of a higher education institution offered the hope of a new start in which both university and neighborhood community members could be centered in the process through public presentations, design charrettes, and surveys. In addition to its on-campus tributaries, significant contributions of water and pollutants to this creek come from surrounding neighborhoods and even an adjacent golf course. The inherent connectivity of water across property boundaries from neighborhood yards to streams made clear from the outset that a broad stakeholder engagement would be critical to project success.

Subsequent community-engaged design established a vision of a restored and accessible stream, embedded within a multifunctional landscape honoring the ecological and cultural values of the site. The benefits of community-engaged design include building local capacity, leveraging creative energy, and engendering a strong sense of spatial agency among future users. University-community design partnerships, in particular, can be highly effective in fulfilling educational and societal goals while also meeting design needs (Pearson 2002). These efforts are most successful when they begin with the predesign phase. In our project, intentional community collaboration began in 2018 with a predesign process that included faculty, student, and community working groups, as well as tours and charrettes that informed the final plan (see Fig. 3). Using the recreational trail as one of the focal points to outreach efforts was useful in helping the community to imagine the project’s universal potential. One of the first specific priorities to be identified and then addressed was the removal of invasive plants along the trail.

Goats were introduced to attack this problem in the early phases. In addition to being an environmentally friendly invasive species removal option, the approach captured people's imagination and feelings in a way that other treatment options would not. The “hooves on the ground” management brought students, university staff, and local families to the site where they asked and learned more about the project. By the time the many non-native plants were removed to make way for the large construction machinery associated with stream rerouting, local community members, including students, had developed an understanding of the overall project goals, and most importantly, had developed the contacts and relationships with decision makers to express their opinions and ask questions. In a sense, the goats acted as ambassadors to help draw attention to the site and get many different people talking about what was happening and what was to come.

A question raised in the public charrette also changed the trajectory of the project. An archeologist and staff member of The Center for Civic Engagement (CCE) asked what might be unearthed when the heavy equipment started digging. He was aware of other ongoing work at UR related to the potential presence of unmarked human remains on campus. His public questioning resulted in the university hiring a Cultural Resource Management Firm to survey the area. Though they did not find evidence of burial sites in the Eco-Corridor, the dig raised awareness of the importance of the historical stories hidden under our feet across campus. Later that year, the University’s first comprehensive report on the history of the land and early leaders of the university, “Knowledge of This Cannot Be Hidden,” was published for the campus community. The report revealed that a few hundred yards from the Eco-Corridor was a space marked on maps as “burial ground” when the land was a plantation. The report also revealed that human remains had been unearthed twice during the construction of nearby university roads and buildings, and no one now knows the location of the remains. These findings sent ripples through the campus, and would take on even more urgency the following year as the city erupted into protest over the symbolism of Confederate statues on its Monument Avenue.

The Cultural Resource excavation of an earthen dam in the Eco-Corridor also raised new and exciting questions about the history of water management in the region, which brought increased interest from historians and water resource professionals. The planning committee asked how they might get more, diverse voices to shape plans for the space to maximize its potential for education. The CCE responded by providing a structure for convening faculty to participate in the Eco-Corridor planning process with a funded faculty learning community (FLC) called the “Eco-Corridor Think Tank.” Ten faculty were selected based on their ideas for a course they could connect to the Eco-Corridor. The group represented a variety of disciplines ranging from economics and business management to English, biology, and sociology. Part of the Think Tank’s work was to provide valuable feedback to the restoration team (RES) during the planning process through face-to-face meetings and surveys. But an FLC also commits to learn together, so the faculty read an Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education (AASHE) resource on how to design a program for “applied sustainability learning projects” (Beaudoin and Brundiers 2017) and met monthly to consider questions such as: “How might this space be best designed to facilitate your class when it is done? What can you imagine there?” Three working groups formed to focus on related themes: Environment in Education, Sense of Place, and Community and Ecological Connectivity.

Faculty and student input changed the course of the design. For example, one of the features prioritized in ranked surveys of the Think Tank group was outdoor classrooms, which were then created using materials such as boulders and logs that were already on-site. As another example, a goal that emerged from conversations with faculty, a class on The Paradox of the Cultivated Wild, and a related student senior thesis, was to leave some spaces wild, so that students might engage with the contrast between the urban wilderness of the Eco-Corridor and other highly manicured spaces on campus. This call for natural “messiness” would not have been a welcome suggestion on the otherwise pristine campus, but the feedback attained during the Eco-Corridor planning process helped make it possible. Faculty, staff, student, and community feedback also imagined other functions for the place—meditation space, sculpture gardens, outdoor teaching opportunities, and even performance space. Many of these ideas were relegated to a “second phase” of the project, around which the University continues to fundraise.

As the project progressed into the construction phase, the Eco-Corridor continued to provide a vibrant hub for learning. Students visited the site (carefully suited up for safety) to learn from the engineers and scientists conducting the work about stream structure and function, aquatic ecology, and water management (see Fig. 4). Student questions, in some cases, led to new data collection about the changing biology and geomorphology of the streams. These student interactions challenged the construction team to break out of a strictly engineering mindset and continuously consider the human dimensions of the project. But for the University of Richmond, our engagement with the project was just getting started when the hard hats and safety vests were put away. It could have been easy to leave this healthier stream as one more feature on a beautifully manicured landscape. Instead, the inclusive process built new interpersonal and intellectual connections, just in time for the COVID-19 crisis.

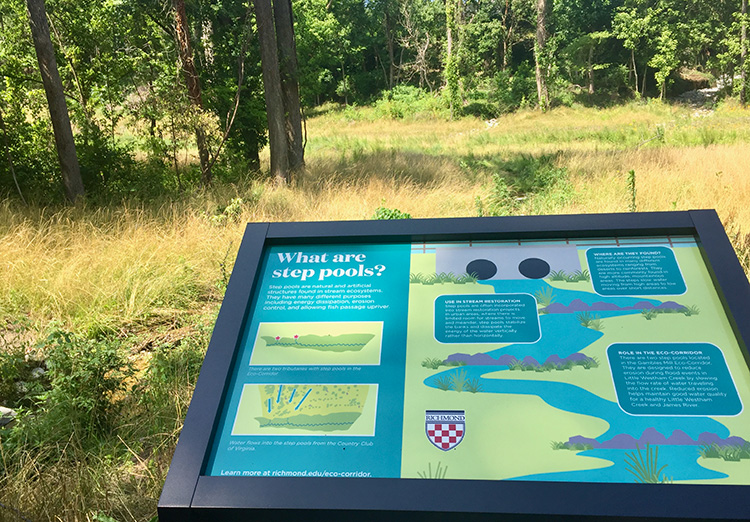

Outdoor spaces on campus took on new importance during the COVID pandemic, and the Eco-Corridor quickly became a destination spot where students and community members could relax, recreate, and interact in person within a safe outdoor environment along a restored urban waterway. New amenities that came out of the community-engaged design process, such as informational signage, gathering spaces, and reflection spots, helped to facilitate these recreational activities (see Fig. 5). The Eco-Corridor has also lived up to its name as a “corridor.” As the pathway has attracted attention, the county added a new sidewalk at one end, helping to facilitate intermodal transport off-campus and making the trail even more popular. The restored, multifunctional landscape has realized the Campus Master Plan vision of providing a safe and attractive walking and biking path leading to the James River. Improvements to and the naming of an existing community garden (now Abby’s Garden) were wildly popular during the pandemic, especially among the university staff. Student interns took leading management roles in the garden. Staff and their families also volunteered additional infrastructure to the site, including a recycled bench and a little free library.

As the pandemic persisted into the 2020–2021 academic year, the CCE convened another group of primarily scientists to reflect on Zoom together while implementing creative instruction around the newly restored stream and uplands. The restoration includes several novel design principles that are implemented in an experimental design along the stream to allow the site to serve as a campus living laboratory for continued monitoring and study (Verhoef and Bossert 2019). Faculty and students began to create signs and videos about the ecology and hydrology of the site, making downstream connections to the Chesapeake Bay. One faculty member installed signposts for visitors to the Eco-Corridor to take and upload photos that will be used to track plant regrowth and seasonal changes over time. Another group of students worked with the pollinator meadows, milkweed, and butterflies in collaboration with a local school. Students who have worked on projects in the Eco-Corridor for their entire four years have begun passing on their experiences (and data) to younger students through capstone projects and linked class presentations. Based on our favorite graduation photo (see Fig. 6), recent graduates have developed a sense of pride and connection to the place.

Moved by the energy of racial reckoning on campus and in the world, students in Eco-Corridor classes declined to hold scheduled Earth Day celebrations at the end of the year as a form of protest, and instead cocreated a scavenger hunt that could be conducted asynchronously. Members of the FLC responded with a request to create a new FLC for 2021–2022, with an increased focus on Humanities classes and faculty. In the largest FLC yet, a class on supply chain management researched the old rail spur that ran through the Eco-Corridor to the campus steam plant, which until recently used coal-generated energy for heating campus. A class on American Indian Literatures considered the first inhabitants of the land, Powhatans and Monacans, and contemplated a land acknowledgment statement. A geography professor interested in telling a different history of the land focused on the Grand Fountain of True Reformers’ time of ownership of the land now included in the Eco-Corridor. One of the authors of “Knowledge of This Cannot Be Hidden” herself participated in the Eco-Corridor FLC, and quickly identified opportunities to make the history of the land more visible in the space. Three classes connected together to study Eco-Corridor history alongside the history of public transportation in Richmond, culminating in dance and theater celebrations of the first local bus drivers to break the color line.

Engagement with the Eco-Corridor now includes, but has moved beyond, the “applied sustainability model” we first considered with the 2017 AASHE report and has taken on the spirit of “emergent strategy” (Brown 2017). Work in the Eco-Corridor flourishes when we focus collaboratively on “solving a problem” as engineers while also “learning together” as humanists and moving toward the future we want to see. What at times seems a barrier to “getting things done”—that no one unit of campus manages or claims ownership over the Eco-Corridor—has shown itself to be a strength, creating the fecundity Adrienne Maree Brown describes as part of emergent strategy. The Center for Civic Engagement and the Office of Sustainability hold space for multiple sectors to participate in an awareness of the place’s past and present in order to help shape a common future. But what we have learned from the project is that these offices operate most effectively when they are part of something much larger. To help realize our desired future, a new Eco-Corridor Stewardship Committee carefully comprised of students, facilities and university staff, faculty from multiple departments and disciplines, and a representative from the local community, has been created with the charge to consider future educational opportunities, conservation and management issues (including invasive species management, landscape maintenance, and storm water infrastructure), recreational use, cultural history, and any threats to the integrity, stability, and beauty of the area.

The types of learning experiences have also expanded and diversified. The area had already been an active teaching space on campus. For years previously, faculty had used the stream and forest, for example, to illustrate the urban stream syndrome or to contrast the sense of place with the neighboring golf course. However, these engagements were primarily with biology and geography classes. The restoration project offered an opportunity to engage a wider community with the problems and possibilities of a waterway. As part of this engagement, we learned that the “downstream” historical connections also could not be ignored, and the project tied together our thinking of the past, present, and future in ways that were entirely unexpected. Once invited, faculty from the sciences, arts, humanities, and business are bringing their respective lenses to the project and that in turn is attracting students who may have never before ventured into this portion of campus. These students learn about water, but they also learn about history and sustainability and civics, at a deep level that characterizes the kind of community engagement that transforms both higher education and our communities, a kind of “systemic engagement” (Fitzgerald et al. 2012). These interconnections have enhanced the educational mission of the university in the same way that the holistic approach to treating the landscape has enhanced the environmental management.

As the Humanities Eco-Corridor FLC wrapped up during Earth Week 2022, we saw an English class painting rocks and “planting” poems shredded in compost and wildflower mix, at the same time as a biology class was sampling macroinvertebrates in the nearby stream with community scientist partners (see Fig. 7). And we begin to wonder: Is this the most important thing to come out of the work so far? Through the continuous widening of constituents, story, and work, the site has become a community learning place. From the community gardeners, to the staff member who collected enough plastic bags to get us a free recycled bench, to the neighbor who stops to ask about the stream restoration and citizen science research opportunities . . . this project is allowing us to reckon with our past and our present realities. It is an experimental lab for building community around water issues. Because water issues are history issues, and business issues, and it is also the opportunity to dance. As Adrienne Maree Brown (2020) says in her essay “What Is Emergent Strategy” in our campus “One Book” selection All We Can Save: “How can we, future ancestors, align ourselves with the most resilient practices of emergence as a species?... [E]mergence shows us that adaptation and evolution depend more upon critical, deep, and authentic connections, a thread that can be tugged for support and resilience.”

Water is always coming from somewhere and going to somewhere, changing the shape of the banks that try to contain it, and making a mockery of our careful plans. With water at the center, this project pushed us toward “resilient practices of emergence” before we had that language to define it. Engaging with those upstream as well as downstream, ancestors as well as future generations, our community grew in size and diversity. Decision making remains messy. But messiness has an upside. The work changes in response to society and the environment, and people find new roles, new connections, new knowledge in the process. It has made the Eco-Corridor a place with so many fans, and so few owners. If the worst problem we have is trying to find ways to coordinate all the enthusiastic people who want to engage, that is a problem we can live with.

Work Cited

Beaudoin, Fletcher D., and Katja Brundiers. 2017. A Guide for Applied Sustainability Learning Projects: Advancing Sustainability Outcomes on Campus and in the Community. Philadelphia: Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education (AASHE).

Brown, Adrienne Maree. 2017. Emergent Strategy: Shaping Change, Changing Worlds. Chico, CA: AK Press.

2020. “What Is Emergent Strategy?” In All We Can Save: Truth, Courage, and Solutions for the Climate Crisis, edited by Ayana Elizabeth Johnson and Katharine K. Wilkinson, 37–38. New York: One World.

Fitzgerald, Hiram E., Karen Bruns, Steven T. Sonka, Andrew Furco, and Louis Swanson. 2012. “The Centrality of Engagement in Higher Education.” Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement 16 (3): 7–28.

Mostafavi, Mohsen, and Gareth Doherty, eds. 2016. Ecological Urbanism, rev. ed. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Graduate School of Design; Zurich, Switzerland: Lars Müller Publishers.

Pearson, Jason. 2002. University/Community Design Partnerships. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Architectural Press.

Verhoef, Leendert, and Michael Bossert. 2019. The University Campus as Living Lab for Sustainability: A Practitioner’s Guide and Handbook. Stuttgart, Germany: Delft University of Technology.