Abstract

The origins of Black people in the United States are primarily told as a story of trans-Atlantic travel tethered to enslavement. However, Black people’s relationships with water and watercraft extend beyond the trans-Atlantic slave ship. Likewise, beyond the Atlantic Ocean are numerous seas, oceans, rivers, and waterways through which Black bodies, minds, spirits, practices, and cultures traverse. This essay charts a developing multimodal project, Black Mariners of the Black Pacific: Reimagining Race, Migration, and Diaspora which explores (trans)national inheritances of the Black Pacific by examining sixteenth to mid-twentieth-century maritime practices of people of African descent, including whalers, commercial mariners, fishers, explorers, shipbuilders, dockworkers, soldiers, and sailors, who settled along the Pacific Coast of what is now the United States. As the project’s methodologies include scholarly writing, public exhibition, a vessel build, and a short documentary, this essay explores the significance of the project’s political praxis of public-facing scholarship.Introduction: The Ocean between Us

When people in America think about Black folks and ships, one type of ship generally comes to mind—the slave ship. Eventually transporting 12.5 million enslaved Africans through the Middle Passage to the Americas, these vessels were key technologies of a centuries-long global human trafficking enterprise that continues to carry sociocultural, political, and economic implications and shape public imagination in critical ways. Because of this significance, the Atlantic Ocean—as the major waterway of the largest forced migration by sea in human history—looms large in narratives that chronicle histories of people of African descent. For example, the origins of Black people in the United States are primarily told as a story of trans-Atlantic travel tethered to enslavement. As such, it is an account of a people torn asunder. Punctuated by lack of agency, separation, and trauma, much of this origin story is rooted in deep-seated truths about the ways in which Black bodies—and the forced labor extracted from them—have been part and parcel of the development and maintenance of the American project.

In her groundbreaking and award-winning work of long-form journalism “The 1619 Project,” which positions slavery and its ongoing consequences at the epicenter of our national narrative, investigative journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones articulates the legacy of this cultural lineage in the project’s introductory article, “America Wasn't a Democracy, Until Black Americans Made It One” (2019). Within this piece, she traces how enslaved Africans in many ways came to be upon the ocean—transfigured not only as socially constructed Black and thus deemed stateless chattel divorced from individuality, humanity, and an ensemble of inalienable rights. But also, how these diverse men, women, and children of various nations eventually collapsed into one amalgamation. Such an account illustrates the narrative power of the Atlantic, and this unprecedented crossing, in popular representations of the Black American experience as a communal site of rupture, rebirth, and remembrance. It is a powerful genesis that Hannah-Jones ultimately argues not only chronicles the beginning of Black people in America, but America itself, given the outsized role Black folks have played in pushing the nation towards fulfilling its democratic promise.

Often eclipsed by this important account within public imagination, however, are histories of Black people’s relationships with water and watercraft beyond the trans-Atlantic slave ship. Likewise, beyond the Atlantic Ocean are numerous seas, oceans, rivers, and waterways through which Black bodies, minds, spirits, practices, and cultures traverse. Such dynamics are at the center of growing scholarship concerned with other bodies of water, and particularly the Pacific, through which we can map Black ontological geographies beyond what historian Paul Gilroy (1993) popularized as the Black Atlantic, a culturally produced transnational formation that connects the Black diaspora across Africa, Europe, and the Americas. Or, as Black Studies scholar Omise’eke Natasha Tinsley articulates, a common investigative thread among this work is the critical query: “Where else can blackness imagine itself besides the Atlantic?” (Allen and Tinsley 2012, 251).

As a Black scholar of Communication interested in the cultural and political work of regional and national origin stories, most notably public remembrances of the American West, I join these efforts as I shift my focus on the politics of memorialized space from the land to the ocean—and specifically portions of the Eastern Pacific. My project, Black Mariners of the Black Pacific: Reimagining Race, Migration, and Diaspora, which has recently attracted attention from museums including the Maritime Museum of San Diego and the Northwest Maritime Center in Port Townsend, Washington, turns to this less explored oceanography to examine 16th- to mid-20th-century maritime practices of people of African descent, including whalers, commercial mariners, fishers, explorers, shipbuilders, dockworkers, soldiers, and sailors, who settled along the Pacific Coast of what is now the United States (California, Oregon, Washington, Alaska, and Hawai'i). Through archival methods, ethnographic study, media production, and public history exhibition, my developing project extends my political geographic understanding of historiography to consider the (trans)national inheritances of the Black Pacific, and the modes through which power is produced in traversing waterways.

This reflective essay charts my journey to this scholarly site of examination. Its first half presents the impetus of my current project, the literature which grounds its examination, and the sets of questions I am working to pursue. And its second half describes my experience in—and commitments to—the political praxis of public-facing scholarship to detail my multimodal research methodologies which include scholarly writing, public exhibition, a vessel build, and a short documentary. In describing these methods, this essay acts as a memo of sorts to myself during a period in which my project is gaining momentum and attracting interest from local museums, partnering institutions, and academic collaborators. In short, instead of waiting for a traditional post-project reflection, in preparation for a particular kind of birth, this written exercise is a reminder to myself of my academic and community-oriented moorings that provide my intellectual journey with particular forms of berth.

Mapping Black Oceanographies: Conceptual Groundings of the Project

Tinsley’s compelling question “Where else can blackness imagine itself besides the Atlantic?” has most likely subconsciously flowed in my marrow since my first regular visits to southern California Pacific beaches as a Black toddler with my Black family during my childhood in San Diego. However, in terms of my own research practice, I place this project within a broader ecology of scholarship concerned with the political and cultural implications of American Western mythology. Given that a central element of these examinations is often land, such a positioning may initially seem counterintuitive. After all, a narrative thread that runs through various incarnations of American Western mythology is a sense of land-based romanticism centered around who arrived upon particular Western land and when, and who settled it and how. That is to say, central to the Myth of the West is a narrative about rugged individuals who were able to bend “wild” land to their will in order to carve out a life and a nation upon it and thus manifest their destinies as the legitimate heirs of a virgin Western bounty.

However, it is important to note the cultural work these land-based narratives perform. As an alibi of colonial activity, these stories are often full of historical inaccuracies and ellipses that erase, obfuscate, or diminish complex racial histories and preserve settler futurity. Take the evolving California origin story, for example, which continually (re)makes race and place in ways that adapt to social change while maintaining notions of American exceptionalism which are key to the coherence and legibility of the nation (Collins 2019). This origin story depends upon a Eurocentric, culturally produced Spanish Fantasy Heritage through which early Anglo settlers in California effectively naturalized their “inheritance” of the region as white Americans in ways that—among other things—obscure the state’s African roots. For example, half of the 1781 pobladores or original settlers of Los Angeles were of African descent, and some were of full Black ancestry, and by 1790, nearly one in five California residents was Afro-Latina/o. The offspring of these Black and mixed-race settlers would become part of Mexico’s Californio1 population—many comprising its rancho-holding oligarchic elite (Fisher 2010). Yet, unlike the early presence of Black people along the Atlantic Seaboard (including pre-US independence), this component of California’s colonial legacy is rarely publicly acknowledged in modern accounts of state history and has largely been forgotten within public memory.

These regional African roots also extend before the 18th century and beyond what is now geographically and politically considered US California. Additionally, this early presence of Black folks was not solely tied to Western land. Not only did free and enslaved African sailors, interpreters, navigators, and soldiers play integral roles in colonial projects in the Americas beginning as early as the 16th century, much of this colonial activity involved nautical travel. In fact, the first navigator to cross the Pacific Ocean—sailing from Asia to the Americas and back in 1564–1565—was an Afro-Portuguese mariner named Lope Martín (Reséndez 2021). Thus, building from these critical African roots within the region, Black Mariners of the Black Pacific: Reimagining Race, Migration, and Diaspora asks what might we learn if we focused on this early Pacific presence of Black people as a particular site of incipient Blackness in America?

Illustrative of these burgeoning research interests is the figure of Allen B. Light, a Black mariner from Philadelphia who in 1834, during Mexican rule of Alta California, departed from the US out of Boston via an American clipper ship named The Pilgrim.2 The following year, The Pilgrim arrived in Santa Barbara where Light ultimately left the ship’s crew. Eventually gaining Mexican citizenship and settling in San Diego, Light became an otter hunter, a Mexican soldier, a small business owner, and at one point was appointed the comisario-general of the National Armada’s Otter Fishing branch. Over a hundred years after his arrival in Alta California, construction workers in Old Town San Diego found Allen Light’s US seamen’s protection certificate3 along with his Mexican naval appointment letter tucked behind two blocks within the walls of an 1829 adobe (Weber 1974). The home had once been owned, not by Light but by his neighbors, a prominent Spanish-Mexican family, the Machados. Upon their discovery, Light’s papers remained relatively obscure, boxed away for decades in the church that had purchased the adobe before they were eventually transferred between a few local archives.4 In 1968, when the adobe became a site of public history within Old Town San Diego State Historic Park, neither the documents nor the man that once owned them were part of the adobe’s central public story in any significant manner beyond a small sign. Light’s documents were mentioned in passing within the adobe’s previous visitor brochure (see Fig. 1) as recently as 2019, presented as a unique “myster[y]” of the historic home—though they are currently not mentioned on the adobe’s webpage (California Department of Parks and Recreation n.d.).

The story of Light, his documents, and the marginalization of both from public-facing historical sites is certainly compelling in itself. However, for the purposes of this project, what is also significant about Light is not only the manner in which he was forgotten in public memory, but the manner in which he arrived in Alta California in the first place: via voluntary oceanic migration. Namely, Light was part of a multiracial maritime workforce that by the early 19th century was nearly 20 percent Black (Bolster 1997). These mainly free Black mariners experienced particular forms of mobility, cultural exposure, and (often precarious) independence. In his maritime journey from Boston to South America, around Cape Horn, and up the Pacific coast of the Americas to Alta California, Light crossed manifold borders and boundaries. And by the time he disembarked in Santa Barbara, the racial ecosystem he encountered in Mexican California diverged in various ways from the US social constructions of race which had previously organized his life upon the Eastern Seaboard. Thus, Light’s emigration presents the opportunity to consider the role such movement could play in mapping the making of race and place in regions that now comprise the Pacific Rim of the United States. In other words, in charting the oceanic movement and settlement of Black mariners such as Light, could we additionally map new understandings of the ongoing production of Blackness in the US? Such an exercise, I argue, would require turning towards the Black Pacific.

In order to position the Black Pacific as a particular realm of cultural connectivity and racial production, I first turn to the seminal work of historian Paul Gilroy who popularized the concept of “the Black Atlantic” within diaspora and cultural studies. In his text The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness, Gilroy breaks from nationalist paradigms as a framework for thinking about cultural history, claiming they are an inadequate way to fully comprehend the “intercultural and transnational formation that [he] call[s] the black Atlantic” (1993, ix). Positioning the ocean as a liminal space, Gilroy evokes the image of the slave ship as a complex site between cultures, nations, and identities which represents the multifaceted, multilayered, and “outernational” positionality of both Black identity and Blackness (17). In examining various cultural products and practices and the mutual “structures of feeling” they produce, circulate, and exchange, Gilroy rejects notions of identity as tethered and rooted to a singular epicentered homeland to instead grant “movement and mediation” primacy in apprehending the nuances of an intercultural and transnational Black Atlantic diaspora across Africa, Europe, and the Americas (3, 19).

Gilroy's centering of Black expression and connectivity—as opposed to rupture—across a vast oceanic expanse is central to my project’s positioning of the Pacific as a site of reimagined diaspora. Additionally, though his fierce rejection of nationalistic paradigms within his analysis may seem contradictory to my interests in the American West and the nation writ large, in certain respects I draw upon his decentering of the nation as an analytical unit. Namely, my project does not rely on a nationalistic paradigm to understand these mariners nor their connections—on the contrary, I evoke these mariners to help us understand the nation. In other words, I intend to examine these moving and complex seafarers who traversed political borders, socially constructed boundaries, and various cultures as a means to apprehend the national project, its limits, productivity, and means of sustainability and repair. As such, it is these Black seafarers themselves then—and not the national unit—that in many ways provide the project its central analytical framework as both a methodology and an object of inquiry. Such an exercise seeks not to support, endorse, or construct a nationalist paradigm, but to reveal the sociocultural and political stakes of one.

Given these interests, my project joins growing scholarship concerned with examining diasporic notions beyond the Black Atlantic by turning to the Pacific as a site of exploration. While no scholarly consensus circumscribes the Black Pacific’s geographic boundaries, much of this work interrogates complex relations that connect African American and North-Pacific Asian populations through “a contact zone of multilateral intercultural exchange” (Taketani 2007, 83; Schleitwiler 2017) and/or among Afro-Amerasians in America (Lucious 2005). However, scholars and artists of the Black Pacific have also evoked the term to describe Black cultural production, diaspora, and transcultural relationships in the Americas including examining Peru’s African musical heritage (Feldman 2006), northern California’s multicultural WWII-era shipyards (Tinsley 2012), and Vancouver’s Black poetry and hip-hop scenes (Smyth 2014). And some Black Pacific scholarship looks beyond the ocean’s rim to highlight particular forms of connectivity within the Pacific’s “dazzling” “sea of islands” (Shilliam 2015, 11; Sharma 2011). Despite these varying cartographic imaginings, a common thread that binds much of this work is viewing the Black Pacific as particularly distinct from the Black Atlantic: as another “node of the black diaspora,” as peripheral to the Black Atlantic, or even representing diasporic cultures that have “moved into unexpected territories”—effectively pushed “off route” in some capacity (Smyth 2014, 390, 19; Feldman 2006).

This notion of unexpected territories grounds my project in its offering of a new way to think about the origins of Black folks in the United States. It is important to note, however, that such an ethos does not presume that the Black mariners within my scope of inquiry considered themselves off-route. In fact, an aspect of this project is examining the cultural inheritances of voluntary maritime migration in tandem with involuntary oceanic movement across the Pacific. Instead, building on work such as Tinsley’s, whose reimagining of the Kaiser shipyards in Richmond, California, during WWII “destabilize[s] and ‘queer[s]’ received stories of race, nationality, gender, and sexuality,” (Tinsley 2012, Foreword) it is the origin story of American Blackness that I intend to take “off route” in my project’s departure from the dominant narrative of the trans-Atlantic slave ship.

In its attention to the Pacific, this project also contributes to foundational scholarship on Black seafaring which does move beyond the slave ship—as much of this work examines trans-Atlantic space and/or ports and harbors along the US Eastern Seaboard (Bolster 1997; Dawson 2009; Finley 2020). Instead, my project asks what might we gain in our understanding of the nation by turning to the Pacific in our examination of (in)voluntary movements of Black bodies? Might a view from the Pacific provide a more adequate framework for understanding the making of race in Pacific regions of the United States as opposed to traditional US frameworks of racial formation that center the American South, enslavement, and Jim Crow (Omi and Winant 2014)? For example, part of this maritime movement occurred during Spanish and Mexican colonization in which frameworks of race were informed by miscegenation, cultural and ritualistic performance, and a long presence of individuals of African descent engaged in colonial projects before Anglo settlers arrived in any significant number (Pitt 1998; Gibb 2018; Restall 2000; Fisher 2010). Through a Black Pacific perspective, might we rethink the seeming universality and permanence of white supremacy, instead realizing it as a relatively new, unfinished, and not-self-sufficient project? Furthermore, what can we learn by examining how these Black mariners communicated, interacted, and culturally exchanged with Indigenous peoples through professional and personal capacities—including the complex ways Black mariners supported and maintained particular forms of empire and/or subverted power regimes (Amadahy and Lawrence 2009; Tuck and Yang 2012)? And how has the suppression of these stories within popular history buttressed notions of race and the nation?

To address these questions, my project deploys multimodal research methodologies including archival methods, ethnographic study, media production, and public history exhibition. What follows is a description of these methods as grounded in an ethos of public engagement.

Project Navigations: Praxis and Methodology

Central to this project is its public-facing ethos. As such, though this project will generate various forms of scholarly writing and interlocution, for the purposes of this essay shared within a journal focused on rich engagements that collaboratively occur within humanities, arts, and design across public life, this section details the project’s multimodal research methodologies which draw upon my experience in and commitments to the political praxis of public-facing scholarship. Specifically, this section focuses on the project’s archival methods, traveling exhibit, vessel build, and documentary film.

At its methodological core, this project begins with archival study. Fundamental to this praxis is my review of primary and secondary materials in order to identify, locate, and recover what I call interstitial evidence of Black Pacific mariners across dispersed and latent archival collections in various photos, letters, diaries, artwork, musical lyrics, cultural ephemera, maritime records, Indigenous materials, and periodicals. This method depends upon wide consultation, including physically and/or digitally visiting local, regional, and (inter)national archives—from the San Diego History Center (which currently holds Allen Light’s seamen’s protection certificate) to the National Museum of American History (whose Curator of the Division of Work and Industry I am in contact with regarding archival materials and physical objects of note).

Informing my archival methods is a philosophy which recognizes the politics of epistemological gatekeeping and values the safeguarding and disseminating of knowledge (re)produced beyond, in addition to, and sometimes in contention with, institutional archives (Pell 2015). This philosophy translates to a methodological design which seeks to uncover obscure historical materials beyond solely consulting traditional archives within libraries, museums, universities, historical societies, and other institutional repositories (see Fig. 2). In order to amplify important yet underheard narratives, I will also scaffold my archival efforts to attend to individual and community-held artifacts and stories. Such a design intervention draws from and builds upon my past collaborative public-oriented scholarship5 (see Fig. 3) on the history of African Americans in rural California which utilized ethnographic methods including speaking with descendants of Black homesteaders in their homes or important communal spaces—thus, viewing their personal photos, letters, keepsakes, and homemade family trees as integral and vital components of community-based archives that could critically inform public storytelling efforts (Collins 2022). This practice is a methodological commitment I also bring into the Black Mariners of the Black Pacific project as I search for archival materials in a wide array of (in)formal repositories.

Figure 3: Trailer for We Are Not Strangers Here podcast series, 2021. Courtesy of Caroline Collins and Cal Ag Roots.

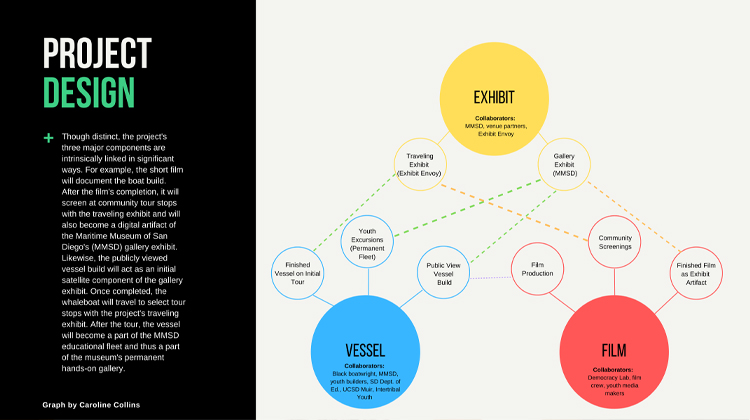

In addition to incorporating archival methods which acknowledge the politics of knowledge production, I also embrace methodological and design practices that work to democratize knowledge delivery. These practices—which are meant to reach diverse audiences beyond traditional modes of scholarship—draw upon digital humanities literature that highlights the ability of archival-based projects rooted in modes of “fugitive” scholarship to create “active space[s] of exchange and ‘encuentro’ between the present and the past” (Cotera 2018, 502, 489). Thus, three distinct yet interrelated interventions ground Black Mariners of the Black Pacific’s public delivery: its

1. public exhibition, 2. publicly viewed vessel build, and 3. short documentary film (see Fig. 4).

Central to this project’s accessibility of scholarship is its mobilization of public exhibition. Drawing upon my experience researching materials for exhibits such as We Are Not Strangers Here: African American Histories in Rural California (2021) and For Race and Country: Buffalo Soldiers in California (2022),6 I have begun curating a public exhibition for the Black Mariners of the Black Pacific project which will be disseminated through two primary modes: a gallery exhibition and a traveling banner exhibit (see Fig. 5).

Both exhibits will incorporate narrative text and analysis, interactive components such as QR codes, and displays of various historical materials uncovered through the aforementioned archival study. The gallery exhibit will additionally include design elements typical of a physical museum exhibit including (super)graphics, fabrications, renderings, hands-on activities, and 3D object display. One major complexity of the gallery exhibit, however, is its planned physical location, the Maritime Museum of San Diego (MMSD). The museum is wholly water based, with all exhibit, archival, performance, administrative, and commercial spaces inhabiting the Museum’s historic and replica vessels and barges in San Diego Bay (including the world’s oldest active sailing ship, Star of India). Thus, unlike traditional museum venues that often offer ample gallery space, including possible design features such as vaulted ceilings and/or empty walls, the Black Mariners of the Black Pacific gallery exhibit will take place upon MMSD vessels.

Though these spatial logistics certainly present a design challenge, they also offer particular opportunities. Specifically, choosing to house the gallery exhibit within the Maritime Museum of San Diego’s water-based locale provides an opportunity to create a seemingly “authentic” nautical visitor experience which can help spark the public imaginary. I also selected the Maritime Museum of San Diego as a partnering institution because of its cultural significance within the region. MMSD hails itself as a cultural heritage site which “serve[s] as the community memory of regional seafaring experience by collecting, preserving, and presenting rich maritime heritage and historic connections with the Pacific world” (Maritime Museum of San Diego 2022). Yet the museum’s current exhibition content, themes, and archival library lack any significant representation of Black maritime activity. Thus, this collaboration also represents the opportunity to critically intervene upon entrenched regional memory culture which so often neglects long histories of Black relationships to water and watercraft in the Pacific. And, at its most forward-looking, it presents the opportunity to create a particular model for ongoing and future reparative memory practices in the region.

For the traveling exhibit, I am also partnering with Exhibit Envoy, a nonprofit organization that specializes in affordable, modular exhibitions. This banner exhibit will tour across various museum partners (including other maritime museums along the Pacific Rim such as the Northwest Maritime Center in Port Townsend, Washington, which has already expressed interest in hosting the exhibit). Within this endeavor, mobility of the exhibit is not an afterthought but a central element at the core of its design. Utilizing public exhibition as a research methodology—and specifically a traveling exhibit—offers another way to visualize the project and widely tell important and undertold history. Such a methodology also critically recognizes the cultural and political work of museum pedagogy (Greenhill 1992; Kosasa 1998), and, in many ways, capitalizes on this work through its (re)telling of repressed history as a critical reappropriation of the archives.

In addition to archival methods and public exhibitions, another vital component of Black Mariners of the Black Pacific is its small vessel build. Like other aspects of this project, this build grows out of my commitment to and experience in multimodal scholarship. Namely, at UC San Diego, I am part of a collaboration that helped establish Black Like Water, an interdisciplinary research collective7 that highlights Black relationships to the natural world as a particular praxis.8 In the summer of 2019, Black Like Water launched our first Black Surf Week. The program, which is open to all UC San Diego undergraduate and graduate students, faculty, and staff interested in learning to surf, explores and discusses Black and African Diasporic relationships to land and water while building community through daytime surfing classes and evening lectures and programming (see Fig. 6).

Figure 6: UCSD Black Surf Week 2020 video. Video by Surfgrass Productions.

In the summer of 2020, on the final day of our Second Annual Black Surf Week, a few of us discussed our hopes for extending our collaboratory’s research and practice. Standing on the shores of Scripps Beach in La Jolla, California, located on occupied, unceded Kumeyaay lands, we faced the vast Pacific as the sun lit the sky orange, announcing its impending descent, and we began to dream aloud—envisioning engaging in boat building as a method of fostering and restoring ancestral connections to the water. Dr. Keolu Fox—as a Kānaka Maoli (Native Hawaiian) scholar—wanted to codesign and construct with community a Polynesian va’a as an innovative site through which to conduct his genomics and Indigenizing biomedical research. And I shared my hopes to build a small vessel with Black youth as a means of rehabilitating their relationships to an overarching origin story of Blackness and watercraft within the US which is powerfully tethered to the confines of the slave ship. Thus, we began to imagine the possibilities of a fleet of culturally relevant vessels that could provide critical methods, sites, and objects of scholarly inquiry.

The vessel build component of the Black Mariners of the Black Pacific project represents a manifestation of this vision. Given the prominence of African American mariners in whaling, this effort will focus on the construction of a 28-foot wooden whaleboat (see Fig. 7) (Bolster 1997; Finley 2020). A culture-bearing Black boatwright, who will serve as an invited artist-in-residence at the Maritime Museum of San Diego, will complete the eight-week build with a group of local Black and Indigenous youth (including Black Indigenous youth) enrolled in the project through partnerships with the San Diego County Department of Education’s Career and College Readiness Program and a local nonprofit, InterTribal Youth. Undergraduate volunteers from UC San Diego’s Muir College Environmental Studies Minor program will also assist in the build. And though the Black whaleboat building tradition is waning, and in some cases extinct, in many locales, I am in contact with an interested Black boatwright who comes from a Black boatbuilding family and who has experience building boats with youth. This publicly viewed boat build will take place on one of the Maritime Museum’s barges on the San Diego Bay and the activity itself will serve as a part of the Maritime Museum’s initial exhibition through contextual signage for visitors and passersby. Building upon the legacy of similar projects of maritime remembrance and (re)construction like Hōkūleʻa9 which inspired cultural renaissance (Dening 2003; Reid 2015; Taitingfong 2021), this vessel build fosters and rehabilitates ancestral relationships to the natural world through reviving a Black historical past in ways that remake the present (Ahad-Legardy 2021).

Upon the vessel’s completion, the youth will take the boat on guided whale-watching excursions in Baja California in coordination with museum, educational, and community partners. This activity not only presents a valuable opportunity for participating youth to engage with water, watercraft, and ocean life. This exercise—which partners Black and Indigenous youth—also engages in what Black Pacific scholar Robbie Shilliam describes as “decolonial science [which] seeks to repair colonial wounds, binding back together peoples, lands, pasts, ancestors and spirits” (2015, 13). In other words, these whale-watching trips are not only organized around the acknowledgement of the historical participation of Black mariners in colonial activities and practices of resource extraction which continue to negatively impact Indigenous land and water resources and sovereignty. These trips also work to recognize the toll of the mutually beneficial twin structures of “super-exploitation of labour and super-dispossession of land organized along lines of race” on which European colonization depends (11). As such, these excursions on the water—between Black and Indigenous youth within a vessel they built together—also present a “rare” research opportunity to “engage with the relationship of [the] (post)colonized to each other” through a praxis of “anti-colonial connectivity” (19, 3).

After these initial excursions for participating youth, the vessel will tour with the project’s traveling banner exhibition at select locations (the Maritime Museum of San Diego will facilitate its travel). Specifically, with assistance from museum and community partners, the vessel will stop at ports of call across the Pacific region for various public storytelling events and nautical workshops with local Black communities and the broader public. However, despite the richness of these planned activities, I was concerned about the vessel’s fate after its initial excursions and tour stops. Namely, given the fact that sustainability is a major component of the project’s design and that I am actively attempting to craft a project with a lasting regional footprint, it was important that the project and its material artifacts engage the public beyond an initial set of ephemeral experiences. Thus, I asked the Maritime Museum of San Diego if the vessel could become a fixture of the museum. Recognizing the significance of such a move, the museum’s leadership has agreed to incorporate the vessel into its permanent educational fleet.

In concert with these efforts towards futurity, I am also beginning to examine possible ways in which the vessel’s future programming can create circumstances in which youth can engage in restorative practices with ocean life beyond whale-watching observation. The 2021 Imagining America conference—which took place days before the submission of this essay—highlighted a promising praxis: the Black feminist practice of “whale whispering” (Harrison 2021). Grounded in the work of Alexis Pauline Gumbs (2020),10 Black artist Michaela Harrison11 uses hydrophone technology to sing and commune with whales off the coast of Praia do Forte, Bahia, Brazil. This healing process—which taps into the generational trauma of the Middle Passage in which enslaved Africans wailed within the bowels of slave ships to a vast abyss of uncaring human enslavers but perhaps to conversing whales—transmutes these past utterances into a contemporary aural remedy which creates a new homeostasis with the natural world. Upon learning of this (re)imagined ancestral practice, I began conversations with some of my university partners to strategize obtaining hydrophones and perhaps institutional support from our world-renowned school of oceanography. Additionally, in the spirit of collaboration and community, I also plan to contact Ms. Harrison to invite her to speak with our participating youth about her project and practice.

Finally, this vessel build will also play a central role in the project’s narrative-based methodologies. Specifically, the vessel build itself will serve as a focal point of a short documentary that will document the boat’s construction interspersed with talking head interviews of scholars and cultural bearers of the Black Pacific in order to provide its audience with important historical context. In many ways, this documentary represents a story about the present and the future and their connections to the past. For example, the film will present an intergenerational, intercultural story which features a young Black boatwright from Carriacou passing on a cultural practice to Black and Indigenous youth from San Diego, California—illustrating in a modern context the intercultural meeting and overlapping of the Black Atlantic and the Black Pacific which often took place during the historical time period the project examines.

In terms of my own scholarly journey, this film also exemplifies an important connection between the past, present, and future. In fact, the entire project—though new in various manners—does not necessarily represent unchartered waters for me. Instead, in many ways, it symbolizes a scholarly return of sorts. In the summer of 2014, months before I was to embark on the first academic quarter of my doctoral studies, I began a years-long collaboration with Native Like Water / InterTribal Youth, a nonprofit focused on revitalizing Indigenous relations to the natural world.12 With UCSD Vice Chancellor of Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion support, I worked with statewide Indigenous youth within InterTribal Youth’s UCSD summer camp for over four summers, designing and teaching writing and media-based curriculums (Collins 2016). In 2016, we collaboratively produced the short film Native Like Water: We’re Still Here (2017) which explores water rights, remembrance, and cultural legacies (see Fig. 8). This film—which was eventually nominated for Best Student Documentary Short in the 2018 San Diego Film Awards—screened in various venues interested in Indigenous youth perspectives on water equity including the 2017 Water Is Life Expo in Flint, Michigan; the 42nd Annual Northwest Indian Youth Conference in Washington State; the San Diego Regional Water Quality Board’s Environmental Justice Symposium; and the 2017 International Youth Congress hosted at the University of Hawai’i Manoa, which also celebrated Hōkūleʻa’s homecoming after a three-year sail around the globe.

Figure 8: Native Like Water: We’re Still Here, 2017. Caroline Collins, Executive Producer and Director. InterTribal Youth. Kaleyedoscope Productions. Nalini Asha Productions. Caroline Imani Collins Productions (film).

Seven years after that first summer of collaboration with Native Like Water, which was before I was formally a doctoral student, I am now a Postdoctoral Fellow, leading a research project that returns to the Pacific—this time to reimagine its role in the origins of Black people in America. And though in this new stage of my academic career my intellectual interventions certainly include writing, publishing, and scholarly lectures, the critical moorings that first anchored my earliest scholarship continue to hail and guide me. As such, I remind myself that fundamental to my scholarly life is cultivating actual embodied experiences, skills, and relationships that span communities, generations, space, and time. Like the waves of my youth which rhythmically pushed and pulled upon my body during my earliest trips to the beaches of San Diego, so does the lure of the Pacific as a site of engaged scholarly inquiry continue to draw me to its depths. And I realize that in this project—I am coming home.

Acknowledgments

Deepest thanks to Riley Taitingfong for critically engaging with this piece during its development and to Patty Ahn, Patrick Anderson, Susan D. Anderson, Angela Booker, Zeinabu Davis, Skip Finley, Keolu Fox, David Igler, Omise’eke Tinsley, and K. Wayne Yang for supporting the incubation of this project. I am additionally grateful to the California Institute of Rural Studies, the UCSD Indigenous Futures Institute, UCSD John Muir College, Al Love (Senior Director of the Career and College Readiness Program of the San Diego County Department of Education), Native Like Water/InterTribal Youth, the Democracy Lab, the Northwest Maritime Center, and the Maritime Museum of San Diego for institutional partnership in the project’s development. This article was made possible by a grant from the Democracy Lab at UC San Diego. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the author and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Democracy Lab, the Communication Department at UC San Diego, or the University. The traveling exhibit for Black Mariners of the Black Pacific will be made possible with support from California Humanities, a nonprofit partner of the National Endowment for the Humanities (visit calhum.org to learn more). The exhibit, vessel build, and documentary planning will be made possible in part by a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities: Democracy demands wisdom.

Notes

1 The term Californio refers to the Spanish-speaking descendants of the original Spanish colonists and escort soldiers in Alta California (Pitt 1998). Born in Alta California, and thus considered “native-born,” most Californios were of mixed Indigenous and/or African descent (Hurtado 1999).

2 The Pilgrim, and the 1834–1835 voyage which apparently included Light, is well known in maritime history as it was immortalized in the memoir Two Years Before the Mast (1840), written by American lawyer and politician Richard Henry Dana Jr. from his diary at sea (Dana (1840) 2020). Though Dana and the ship’s log do not specifically name Light, first-hand accounts from Light’s contemporary and one-time hunting partner, explorer, fur trapper, and memoirist George Nidever, claim that Light arrived in Alta California via The Pilgrim (Nidever 1937). Other early California histories also place Light on The Pilgrim and/or in the region during this time (Smythe 1907; Beasley 1919).

3 Often carried by US crewmen as proof of citizenship, these notarized documents—which generally featured the US seal and a brief physical description of its holder—were meant to provide a means of protection against the 17th–19th–century British practice of impressment or the forcible taking of men into their naval force in order to sustain the royal military (Zimmerman 1925). For free Black mariners these documents offered double protection, also providing proof of their free status (Putney 1987).

4 Before being boxed away the papers of the “Negro sailor” were put on display during the dedication rites of the newly refurbished church which had recently purchased the Machado adobe (San Diego Union 1948; Weber 1974).

5 This scholarship culminated in a traveling banner exhibit (14 February 2021–23 October 2022) and a six-episode podcast series called We Are Not Strangers Here: African American Histories in Rural California (https://cirsinc.org/cal-ag-roots/). This project is a collaboration between the Cal Ag Roots project at the California Institute for Rural Studies, Susan Anderson of the California African American Museum, Exhibit Envoy, and Dr. Caroline Collins of UC San Diego. This project was made possible with support from California Humanities, a nonprofit partner of the National Endowment for the Humanities, and the 11th Hour Project at the Schmidt Family Foundation.

6 For Race and Country: Buffalo Soldiers in California. 13 April–22 October 2022. California African American Museum, Los Angeles, CA, is curated by Susan D. Anderson, history curator, with consultant Anthony J. Powell and researcher Caroline Collins. https://caamuseum.org/exhibitions/2022/for-race-and-country-buffalo-soldiers-in-california.

7 This collective is led by Faculty Advisors Angela Booker, Keolu Fox, and K. Wayne Yang. Black Like Water programs are made possible with support from the UC San Diego Black Resource Center, African American Studies, UCSD Recreation, the UCSD Colleges, Scripps Institution of Oceanography, and the UCSD Office of the Vice Chancellor for Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion.

8 Black Like Water seeks to “promote healing, restoration, and sovereignty in ways that do the liberatory work of not only combating anti-blackness and interrupting structural racism, but in manners that also celebrate the Black diaspora, acknowledge ancestral practices and knowledge, and imagine Black futures.” https://www.blacklikewater.com/about.

9 The construction and early voyages of maritime revival projects like Hōkūleʻa, a performance-accurate Polynesian double-hulled voyaging canoe launched in 1975 by the Polynesian Voyaging Society not only helped inspire the Hawaiian cultural renaissance, but influenced aligned projects in other islander communities, generating new Indigenous traditions and creating opportunities for cross-movement solidarity.

10 Using the “subversive and transformative lessons of marine mammals,” Gumbs’ latest work, Undrowned: Black Feminist Lessons from Marine Mammals (2020), offers a book-length meditation for humans seeking healing, restoration, and social justice (7).

11 Washington, D.C. native Michaela Harrison harnesses the “healing, transformational power of music through song” in her artistic career. https://www.michaelaharrison.org/who-i-am.

12 Native Like Water “prepares Indigenous youth and adults in science, outdoor education, conservation, wellness, and cultural self-exploration” through programming in California, Hawai’i, Jamaica, and Panama. https://www.nativelikewater.org/.

Work Cited

Ahad-Legardy, Badia. 2021. Afro-Nostalgia: Feeling Good in Contemporary Black Culture. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Allen, Jafari S., and Omise’eke Natasha Tinsley. 2012. “A Conversation ‘Overflowing with Memory:’ On Omise’eke Natasha Tinsley’s ‘Water, Shoulders, Into the Black Pacific.’” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 18 (2–3): 249–262. https://doi.org/10.1215/10642684-1472881.

Amadahy, Zainab, and Bonita Lawrence. 2009. "Indigenous Peoples and Black People in Canada: Settlers or Allies?" In Breaching the Colonial Contract, edited by Arlo Kempf, 105–136. New York: Springer, Dordrecht. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-1-4020-9944-1_7.

Beasley, Delilah Leontium. 1919. The Negro Trail Blazers of California: A Compilation of Records from the California Archives in the Bancroft Library at the University of California, in Berkeley; and from the Diaries, Old Papers and Conversations of Old Pioneers in the State of California. It Is a True Record of Facts, as They Pertain to the History of the Pioneer and Present Day Negroes of California. No. 17. Los Angeles: Times Mirror Printing and Binding House. 167–186.

Bolster, W. Jeffrey. 1997. Black Jacks: African American Seamen in the Age of Sail. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

California Department of Parks and Recreation. n.d. “La Casa de Machado y Stewart (The Machado-Stewart House): The Machado-Stewart Museum [Information sheet].” Accessed April 15, 2019.

Collins, Caroline. 2016. “NGOs and Educational Partnerships in the USA.” In Education and NGOs, edited by Lorraine Pe Symaco, 167‒186. London: Bloomsbury.

. 2019. “Manifest Re-Destined: The Politics of Remembering and Forgetting in the American West.” PhD diss., University of California, San Diego.

, host, producer. 2021. We Are Not Strangers Here: African American Histories in Rural California. Cal Ag Roots (podcast). Santa Cruz: California Institute for Rural Studies. https://cirsinc.org/2021/03/25/we-are-not-strangers-here-african-american-histories-in-rural-california/.

. 2022. “When Do You Stop Arriving? The ‘We Are Not Strangers Here: African American Histories in Rural California’ Project.” California History 99 (4): 51–81.

Cotera, María. 2018. "Nuestra Autohistoria: Toward a Chicana Digital Praxis." American Quarterly 70 (3): 483–504. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/704334/summary?casa_token=LcpHM6FKeUcAAAAA:gzp3oaUloL6F-gCvqgyBhJ0bvB9fnadjiWaUtIrpIaVasQLIyPacHu6FZbChcx3mzNwGC0PIHw.

Dana, Richard Henry, Jr. (1840) 2020. Two Years Before the Mast. Orinda, CA: SeaWolf Press.

Dawson, Kevin. 2009. "Swimming, Surfing, and Underwater Diving in Early Modern Atlantic Africa and the African Diaspora." In Navigating African Maritime History, edited by Carina E. Ray and Jeremy Rich, 81–116. Research in Maritime History, No. 41. St. John’s, NL: International Maritime History Association.

Dening, Greg. 2003. “Voyaging the Past, Present, and Future: Historical Reenactments on HM Bark Endeavour and the Voyaging Canoe Hokule’a in the Sea of Islands.” In The Global Eighteenth Century, edited by Felicity A. Nussbaum, 309‒324. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Feldman, Heidi Carolyn. 2006. Black Rhythms of Peru: Reviving African Musical Heritage in the Black Pacific. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press.

Finley, Skip. 2020. Whaling Captains of Color: America's First Meritocracy. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press.

Fisher, Damany M. 2010. Discovering Early California Afro-Latino Presence. Berkeley: Heyday.

Gibb, Andrew. 2018. Californios, Anglos, and the Performance of Oligarchy in the U.S. West. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

Gilroy, Paul. 1993. The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness. New York: Verso.

Greenhill, Eileen Hooper. 1992. Museums and the Shaping of Knowledge. London: Routledge.

Gumbs, Alexis Pauline. 2020. Undrowned: Black Feminist Lessons from Marine Mammals. Chico, CA: AK Press.

Hannah-Jones, Nikole. 2019. "America Wasn't a Democracy, Until Black Americans Made It One." The New York Times Magazine, August 14.

Harrison, Michaela. 2021. “Tributaries.” Friday Morning Plenary, Imagining America Conference, Zoom, October 22, 2021.

Hurtado, Albert L. 1999. Intimate Frontiers: Sex, Gender, and Culture in Old California. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Kosasa, Karen K. 1998. "Pedagogical Sights/Sites: Producing Colonialism and Practicing Art in the Pacific." Art Journal 57 (3): 46–54. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00043249.1998.10791892?casa_token=Sum7dYx1G0oAAAAA:-DavKlJW6Fhq4O8IFIbeu3HGR5pix8ggesFHGsAEkwVDkOm-Yi1HKTSs5rZbbp7-LjYAMqWzmMoj.

Lucious, Bernard Scott. 2005. "In the Black Pacific: Testimonies of Vietnamese Afro-Amerasian Displacements." In Displacements and Diasporas, edited by Wanni W. Anderson and Robert G. Lee, 122–156. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. https://doi.org/10.36019/9780813537511-009.

Maritime Museum of San Diego. 2022. “About the Maritime Museum of San Diego.” Accessed May 5, 2022. https://sdmaritime.org/about-the-maritime-museum/.

Nidever, George. 1937. The Life and Adventures of George Nidever 1802–1883. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Omi, Michael, and Howard Winant. 2014. Racial Formation in the United States. New York: Routledge.

Pell, Susan. 2015. "Radicalizing the Politics of the Archive: An Ethnographic Reading of an Activist Archive." Archivaria 80 (November): 33–57. https://archivaria.ca/index.php/archivaria/article/view/13543.

Pitt, Leonard. 1998. Decline of the Californios: A Social History of the Spanish-Speaking Californians, 1846–1890. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Putney, Martha S. 1987. Black Sailors: Afro-American Merchant Seamen and Whalemen Prior to the Civil War. New York: Greenwood Press.

Reid, Joshua L. 2015. The Sea Is My Country: The Maritime World of the Makahs. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Reséndez, Andrés. 2021. Conquering the Pacific: An Unknown Mariner and the Final Great Voyage of the Age of Discovery. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Restall, Matthew. 2000. "Black Conquistadors: Armed Africans in Early Spanish America." The Americas 57 (2): 171–205. https://doi.org/10.1353/tam.2000.0015.

San Diego Union. 1948. “Ancient Papers Found in Adobe Wall Here." San Diego Union, April 18, 2-A. Readex: America's Historical Newspapers.

Schleitwiler, Vince. 2017. Strange Fruit of the Black Pacific: Imperialism’s Racial Justice and Its Fugitives. New York: New York University Press.

Sharma, Nitasha. 2011. "Pacific Revisions of Blackness: Blacks Address Race and Belonging in Hawai'i." Amerasia Journal 37 (3): 41–60.

Shilliam, Robbie. 2015. The Black Pacific: Anti-Colonial Struggles and Oceanic Connections. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Smyth, Heather. 2014. "The Black Atlantic Meets the Black Pacific: Multimodality in Kamau Brathwaite and Wayde Compton." Callaloo 37 (2): 389–403. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/544941.

Smythe, William Ellsworth. 1907. History of San Diego, 1542–1907: An Account of the Rise and Progress of the Pioneer Settlement on the Pacific Coast of the United States. San Diego: History Company.

Taitingfong, Riley Ilyse. 2021. “Editing Islands: (Re)Imagining Isolation in Gene Drive Science and Engagement.” PhD diss., University of California, San Diego. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1593t059.

Taketani, Etsuko. 2007. "The Cartography of the Black Pacific: James Weldon Johnson's Along This Way." American Quarterly 59 (1): 79–106.

Tinsley, Omise'eke Natasha. 2012. "Extract from ‘Water, Shoulders, Into the Black Pacific.’” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 18 (2–3): 263–276. https://doi.org/10.1215/10642684-1472890.

Tuck, Eve, and K. Wayne Yang. 2012. "Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor." Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 1 (1): 1–40. https://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/des/article/view/18630.

Weber, David J. 1974. “A Black American in Mexican San Diego.” Journal of San Diego History 20 (2). https://sandiegohistory.org/journal/1974/april/light.

Zimmerman, James Fulton. 1925. Impressment of American Seamen. New York: Columbia University.