Abstract

Utilizing a combination of critical pedagogy and story-based theater, Latina feminist methodologies and theories and participatory development, this theatrical adaptation of Carolina Osorio Gil's master's thesis demonstrates how collaborative story-based theater can create spaces of knowledge exchange that are not attainable from common hierarchical trainings in community development projects. This is a dramatic retelling of the events that unfolded during two workshops with women in Chiapas, Mexico, and the time leading up to the workshops and since. We hope that in listening to these women’s voices, in addition to reading their testimonios, you will feel as though you, too, might be a collaborator in our work. Providing deep, critical and creative analysis of data in the form of transcriptions, photography, and audio clips which we have curated specifically for this production, we offer key insights to utilizing this type of cocreated woman-focused workshop.This is a dramatic retelling of the events that unfolded during two workshops with women in Chiapas, Mexico, and the time leading up to the workshops and since. We hope that in listening to these women’s voices, in addition to reading their testimonios, you will feel as though you, too, might be a collaborator in our work.

A Note on Translation:

This script is written mostly in English, with some Spanish which is presented in two ways. The two-column format indicates that the text is a word-for-word transcription and translation, based on interviews I conducted as part of my Master’s thesis. Translation in the body of the text indicates that creative license has been used with that text/speech.

CHARACTERS

| CARO, a social science researcher | CITLALLI, a biologist from a water NGO |

| AUTHOR, the same researcher | OLIVIA, an environmental organizer from a water NGO |

| ERIKA, an engineering professor | CYNTHIA, a local community organizer |

| DEBRA, an established professor | YONALLI, a municipality government rep |

| RUTH TRINIDAD GALVÁN, academic goddess | 5 MUJERES BRIGADISTAS,2 young women ages late teens to 20s |

| BELL HOOKS, academic goddess | 2 MEN |

SETTING

The action takes place in various locations in rural towns in a small municipality called Berriozábal in the state of Chiapas in southern Mexico, though it could take place anywhere. The locations may be outdoors or indoors, depending on the availability of the set.

Stage Right is a separate area where AUTHOR is giving a presentation at a conference. The images and videos will be projected behind her, and can be anywhere on the upstage wall. Upstage of her sit two special guests, RUTH TRINIDAD GALVÁN and BELL HOOKS, both dressed in flowing clothing, on tall stools.

ACT I

Scene 1: Setting the Stage / Sharing Our Historias

Lights up. Workshop 1, Village of Caracol. All of the women sit in chairs in a circle, Stage Left. Mujer Brigadista 1 is standing in front of her chair.

MUJER BRIGADISTA 1: Nos escucharon cada historia. Yo escuché y me escucharon a mí.(Ella se sienta.) |

WOMAN BRIGADIER 1: Each of our stories was heard. I listened, and I was listened to. (She sits.) |

Sitting in the folding chairs in a circle in the mostly empty multiuse building in this village, our collective nervous anticipation and hesitation about the theater workshop ahead are palpable. I briefly provide instructions for the preliminary Story Circle activity (Davis 2019). With some encouragement from the other visiting facilitators, las Mujeres Brigadistas slowly, one by one, open up to sharing around the prompt of their experiences with water in their communities. Slowly, with some trepidation, we make our way around the circle, each sharing a two-minute-or-less story. A similar narrative begins to unfold in the stories—one that I don’t expect. The stories shared by the women converged around one primary theme: their fear of the river. (Lights down.)

This is a story of water, women, and story-based theater workshops in two of 46 rural communities within the Municipality of Berriozábal in Chiapas, Mexico, in April 2019. During these workshops (and in the planning of them), bonds were created that facilitated deep collaboration, knowledge sharing, and co-imagined futures between mujeres (women). Utilizing a combination of critical pedagogy (Freire 2013, 2015) and story-based theater (Boal 1985, 2002), Latina feminist methodologies and theories (Sandoval 2000; Anzaldúa 2012), and participatory development (Cornwall and Edwards 2014), our project demonstrates how collaborative story-based theater can create spaces of knowledge exchange that are not attainable from common hegemonic hierarchical training workshops in community development projects. It is our hope that in listening to these women’s voices, in addition to reading their testimonios and seeing their photos, you will feel as though you, too, might be a collaborator in our work. Providing deep, critical, and creative analysis of data in the form of transcriptions, photography, and audio clips which we have curated specifically for this production, we offer three key advantages to utilizing this type of cocreated woman-focused workshop, as well as presenting some challenges and limitations to this work. Act I explores story-circle methodology and nonhierarchical pedagogy praxis like coconstructed interviews that gently allow for participants’ stories and lived experiences to be heard and bonds between women to grow; Act II looks at how collaborative arts allow for healing connections for women to weave together with the agenda of improved water governance within entangled power dynamics and a patriarchal system; and Act III shows how these two specific workshops created circumstances for women to share their deep connections and experiences with water in their homes and communities.

Beyond the implications for ethical and participant-focused feminist development work, this project prioritizes and privileges the Mujeres Brigadistas—it is to them whom we dedicate this work. They are not only the stars of the show, but also form part of the directorial ensemble of the workshops and the work. Theirs is the first word of this piece and the last. In the spirit of holding them with the utmost respect, all photos and multimedia materials of the participants have been de-identified. The individuals in the photos and named in this script are the facilitators of the workshops who collaboratively organized this project and with whom Caro continues to work.

Lights up. Back to Workshop 1 Story Circle.

Mujeres Brigadistas get up and exit. This leaves CARO, ERIKA, DEBRA, CITLALLI, OLIVIA, and CYNTHIA onstage. They stand in a group, acting out the actions CARO describes.

I thought the women would share about their day-to-day experiences with the water that they use in their homes, so I’m really surprised that the stories focus on the dangers of the river. Before coming here, we talked about our goals as leadership building. Citlalli, Olivia, ¿Qué pensaron ustedes? ¿Se les hizo útil el taller? | What are your thoughts? Is this workshop helpful for your goals?

Las historias del río me ayudaron a entender de los asuntos de salud de las mujeres, especialmente la historia de la mujer que se le infectó el pie por la concha que pisó por el río. | The stories about the river helped me understand about health concerns, especially the story about the woman who got the infected wound from walking to the river to collect water.

Del punto de vista del municipio, estas historias nos ayudan a Cynthia y a mí para entender los retos que tienen las mujeres sacando agua del río Sabinal. | From the municipality’s point of view, these stories helped Cynthia and I to better understand the challenges women have in accessing water from the Sabinal river.

Sí, de acuerdo. Nos dimos cuenta que tan peligrosas son las rutas para caminar al río, y el problema que muchas de ellas no saben nadar. | Yes, I agree. We realize how dangerous the routes are to walk to the river, and the problems because most of them can’t swim.

En otras oportunidades trabajando en Tuxtla Gutiérrez he visto que tan importante es que como ingenieros escuchemos a las comunidades cuando estamos trabajando en temas del uso de agua. | I’ve seen in other work I’ve done in Tuxtla Gutiérrez how important it is that we engineers listen to the people who live near the river when we are working to resolve engineering problems about water use.

As a culture studies scholar, my takeaway in the stories is how they paint a visceral picture of these women’s lifelong relationship with the river from their childhood to the present day.

With the workshop, las Mujeres Brigadistas create frozen theatrical scenes, or tableaux, of their stories. And I notice that when they reflect on the experience after the story circle is complete, the significance and relevance of their stories becomes apparent.

Lights down.

The workshop we just described was the first in a set of two workshops that we carried out. Our principal academic team consists of Carolina Osorio Gil (Caro), theater artist and PhD student; her longtime collaborator and mentor Dr. Debra Castillo; and longtime collaborator, engineering professor Erika Díaz Pascacio from Chiapas. Erika facilitated a connection with a regional water NGO, Cántaro Azul, which has been working with the Municipality of Berriozábal in Chiapas to design and carry out a women’s empowerment project called Mujeres Brigadistas (Women Brigadiers), which hopes to facilitate knowledge sharing by the women of the 46 villages of the municipality about water. The ultimate goal was to have these women’s unique and deep knowledges of the water they live with and consume inform community water governance, and perhaps for them to even serve as water officers on their community governing committees. As is the case in much of the world, water is a huge issue for rural communities in Chiapas due to the changing rainfall patterns linked with the current climate crisis, as well as water health issues. Many of the villages don’t have running water and depend on water catchment systems, as well as, when there is insufficient rainfall, purchasing tanks of water for their communities. After each workshop, Caro was able to interview a few of the participants to learn more specifically about their experiences, day-to-day, with water in their daily lives and homes, which helped me learn more specifically what the issues they experience are. We will come back to this later.

Scene 2: Going with the Flow—When Things Don’t Go as Planned

Lights up on Workshop 2, Village of Camelias. CARO, OLIVIA, CITLALLI, and ERIKA start sitting in four chairs to represent a car and then get up and move as indicated by CARO, pantomiming the actions that CARO describes.

I’m feeling calmer now, with one successful workshop under our belts two days ago. Olivia, Citlalli, Erika, and I giggle and talk excitedly on the car ride on our way to the second village, and the second workshop. As we approach, we are surprised to stop, not in front of a community space like the first workshop, but at one of the women’s homes. I wonder how we are going to fit 20-plus Mujeres Brigadistas in this space, but I smile and introduce myself to the people—particularly the two men (the woman of the house’s husband and father)—who mill around the outside of the house just within ear shot (and remain there for the entirety of the workshop). This predicament quickly reminds me that we are indeed in patriarchal communities and having a private space for just women, as we had for the first workshop, is a luxury that we cannot take for granted. And this is just the start of the surprises that our second day of theater workshops with the Mujeres Brigadistas brings us.

Although the initial plan for the workshops conducted in the two communities was identical, due to circumstances outside of our control, such as half the participants being over an hour late due to communication and transportation issues (there is no cell service in this area; communication is done via two-way radio) and most of the women who are on time bringing their young children, we have to be nimble and adaptable in our work. This meant that the planned curriculum is thrown out the window. And, so, the second workshop ended up taking a very different form, which presented exciting opportunities, such as the chance to explore “baby warmups” (body warmups with babies—real or imaginary—in arms) as well as a makeshift interview activity. For the interview activity, each Mujer Brigadista was paired up with one of the visiting collaborators. Together, as a group, we come up with questions about each other’s daily lives, and specifically around daily water experiences.

Lights up Stage Left. Las mujeres / the women stand in a semicircle.

(to the women): ¿De dónde viene el agua de tu comunidad y cómo llega a tu casa? | Where does the water you use in your community come from and how does it get to your home?

MUJERES BRIGADISTAS add that they want to know other things about the visiting women, and the FACILITATORS (the visitors) agree. Together, they add questions.

¿Qué te gusta estudiar? | What do you like to study?

¿Qué vas a hacer de comida? | What are you going to make for dinner? (They excitedly add more suggestions.)

Through these improvised interviews, we created a discursive space as well as a physical space for us to interact as women—to be vulnerable and silly together, to listen to each other’s delicious menu plans and favorite topics to think about, even if there are men literally just outside the doorway. The times that we spend in more informal conversation as well as facilitated discourse through the interviews and the story circle are the sort of convivencia that Ruth Trinidad Galván (2015), Sofia Villenas (2005), and others write about. On utilizing convivencia as a Latina feminist methodology, Trinidad Galván says:

Those moments of real interaction and learning took place in the sheer moments of living, spending time together, and being each other’s ears and companion (2015, 96–97).

Convivencia, the act of spending time together, has its root in the Spanish verb vivir (“to live"); it happened organically through working together and living amongst each other. However, in the case of these two theater workshops, convivencia is at times facilitated, sort of “fast-tracked,” through activities of deep connection like the interviews in Workshop 2 and the story circle in both workshops. At other times, convivencia happened naturally while we mingled, waiting between activities, or while we got a bite to eat when sandwiches arrived during the workshops. The fluid, flexible, and relaxed nature of our workshops creates space and time for deep convivencia among women, which facilitates trust and cocreated priorities for water knowledge work.

During the reflection activity conducted at the end of each workshop (called the Spider Web), one of the women shares how her favorite part of the day had been doing the interview.

MUJER BRIGADISTA 2: La pude conocer un poquito más, y ya agarro más confianza con ella. Ya nos podemos hacer hasta amigas. |

WOMAN BRIGADIER 2: I got to know her a bit more, and I am trusting her more. Now we can even be friends. |

TODAS: Ahhh . . . ¡Hasta amigas! (ríen) |

ALL: Wow! . . . Even friends! [they laugh] |

MUJER BRIGADISTA 2: Ya me invitó a comer. |

WOMAN BRIGADIER 2: She invited me over for dinner. |

“¡Hasta amigas! Even friends!” (We all laugh as a group.) Imagine! The feeling of becoming friends with someone, someone who seems so different from you, who minutes before was a stranger from an unfamiliar place. Now, after just a couple of hours together and one 15-minute-long informal conversational interview, she feels like your amiga that you want to invite over for dinner.

¿Y, qué vas a hacer de cena? | And, what are you making for dinner?

Tengo un pollo guisando para server con tortillas que voy a hacer. | I have a chicken stewing that I am going to serve with tortillas.

Ay eso suena tan delicioso. Si, por favor ¡me tienes que inviter a comer! | That sounds delicious! Yes, please invite me to eat sometime!

Both women laugh.

The feeling of deep comradery that these collaborative and flexible activities facilitate, to even create bonds of friendship, was invaluable to the collaborative work of water governance that is the ultimate goal of these workshops. During the Spider Web reflection activity, when asked about the most memorable part of the workshop, all of the facilitators specifically mention the moments of close connection and opportunity to truly get to know each other. Another difference for the second workshop is that we are joined by Yonalli, Head of Environmental Activities for the Municipality.

Enter YONALLI, Municipal Government Official.

(now facing YONALLI as if to interview her): Can you tell me how this experience shaped your view of the Mujeres Brigadistas, and your own relationship with them as a member of the governing political body?

YONALLI: Me gustó mucho poder tener esta convivencia tan cercana hacia las chicas porque permitió conocerlas un poquito más. Conocer cuales son las necesidades lejos de las obvias que ya tienen con el tema del agua. Pero también ver que ellas quieren seguir capacitándose y quieren seguir aprendiendo en diferentes temas. Y encontrar que tengo tanto parecido con ellas también, ¿no? Entonces eso me motiva adelante, a seguir trabajando arduamente por ellas. |

YONALLI: I really liked being able to have that intimate “convivencia” with the girls because it allowed me to get to know them a bit better. To know what their needs are apart from the obvious ones they have around water issues. But also to see that they want to keep building their skills and learning about different topics. And, also, to find that I have so much in common with them, right? That motivates me to move forward, to keep working hard for them. |

Through the informal interview process, Yonalli stated that she was able to find commonalities between herself and the woman she interviewed, leading her to find new motivations in how she approaches her work for the local government. Typically, municipal officials like Yonalli do not get to interact in an intimate way, such as sharing a meal or a chat, with community members, much less participate in a collaborative art-making activity. In this interview, Yonalli identified two ways that the workshop, and specifically what she refers to as “esta convivencia tan cercana” | “this close/intimate convivencia,” affects her understanding of the Mujeres: 1. Yonalli had an opportunity to learn about interests and concerns that her female constituents have beyond the limited scope of the Municipality’s water project; and 2. She was able to find commonalities between herself and the women—in other words, she was able to relate to them. This relatability is a stepping stone to empathy, which is one of the most valuable known effects of collaborative community-based theater.

One of the Mujeres, with her young daughter in her lap, conducts an informal conversational interview with Erika. The woman takes a bite of the sandwich in her hand and both women have their beverages on the floor next to them. Sharing a meal and a conversation is a type of convivencia.

Scene 3: Analysis

CARO sits on the floor, with a stacks of paper and her laptop.

While analyzing videos and photos, as well as my field notes of the workshops, several vital aspects of convivencia stand out to me:

- Time/space for flexibility to allow for needs (specifically in Workshop 2), especially to have and include their children.

- In turn, that opened up opportunities for more organic activities such as the makeshift interviews.

- Food/sharing a meal. In both of the workshops, the Municipality provided lunch and it was an important aspect of our time together. It was also an opportunity for the organizers to demonstrate gratitude to the Mujeres through providing sandwiches and drinks. Sharing a meal inevitably facilitates more relaxed conversation and convivencia.

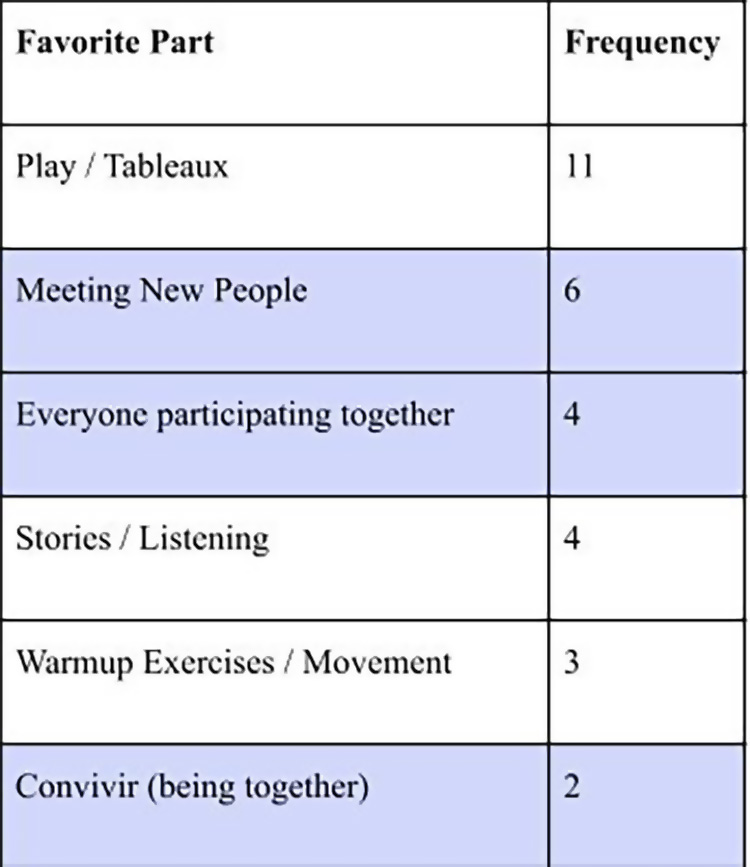

As can be seen in this table, during the Spider Web reflection activity, 12 women listed their favorite part of the workshops as either meeting new people (6), all of the women participating together (4), and having the opportunity to convivir together (2) (the women specifically used the term convivir in their response). In fact, all three of these responses fell within the category of convivencia, about spending time together, getting to know each other, and just being with other women. Even becoming friends—hasta amigas. Thus, all of the women—all of us—felt especially aware of and grateful for some time spent together, getting to know each other, and just being together. This is what convivencia looks like.

Trinidad Galván relates convivencia with sobrevivencia (survival) and what she calls supervivencia (going beyond surviving; thriving):

The need to create spaces and places that sustain was a crucial determinant for their (the women’s) supervivencia. This is precisely where convivencia ties to supervivencia. Our vivencia, according to Ortega y Gasset (2007), is made of the mundane insignificant occurrences and every so often of great happenings, many times painful and others joyous, but always a relationship with a circumstance and others. While both words speak of living and being in the moment (vivencia), one emphasizes a sort of communion with others, a togetherness (convivencia), while the other word (supervivencia) claims a beyondness (super/sobre) to mere survival (2015, 113–114).

ACT II

Scene 1: The Story of the Partera (Midwife) / Women Reinforcing the Patriarchy

Lights up on AUTHOR.

Next, we will share stories from two of the facilitators—Olivia and Cynthia—stories that speak to the complex nature of gender and relationships between women in these communities. These stories are about the ways in which women superaron (came out ahead in the vein of supervivencia) and, during these workshops, have the chance to superar together. These stories, in turn, are shared and are thus accessed by me now sharing them with you in this moment of convivencia between us.

Lights up. CARO, OLIVIA, ERIKA, and CITLALLI are in the car.

Y, Olivia, cuéntanos un poco del trabajo que has estado hacienda con mujeres en estas comunidades, o en otras comunidades parecidas. | So, Olivia, tell us a bit about your previous experience with women in these villages, or in similar communities.

OLIVIA: El año pasado realizé estudios diagnóstico a puras mujeres. A puras mujeres. Para preguntar su estado de ánimo. ¿Cómo se sentían ellas? ¿Qué tanto han aprendido? Y yo me quedé con muchas experiencias o sea que realmente hasta a mí me daban ganas de llorar. Porque cuando empezamos a hablar entre puras mujeres, empezaron como a platicar, ¿no? Y se desenvolvían. O sea tanto que si teníamos una hora para esa actividad nos llevaban dos horas, tres horas. |

OLIVIA: Last year I carried out some diagnostic research with strictly women. To ask the state of their willingness (morale). How did they feel? How much had they learned? And I was left with many experiences, in other words, ones that really even made me want to cry. Because when we started talking amongst pure women, we began to like, talk, right? And they got comfortable. So much so that if we had an hour for the activity, we would take two hours, three hours for it. |

Olivia uses the phrase “puras mujeres” to indicate workshops and spaces where she has been with only women and what happens when you get together among only women. When Olivia, as an organizer, facilitates spaces for women to be in convivencia together, they take time to “desenvolverse” (unwind, open up) and end up sharing deep stories of pain, survival, and “supervivencia” (Trinidad Galván 2015), as is this story of the doula that follows.

OLIVIA: Porque incluso decía una, una experiencia de señora. De una partera. Que cuando ella se empezó a capacitar, me dice, <<mi esposo me dió permiso>> ¿no? <<mi esposo me apoyó. Pero a mi suegra no le gustó. Y le buscó otra mujer. Y la metió en mi casa.>> Así y [carraspea] cuando ella me platicaba y yo dije, <<¿cómo?>> dije, <<pero si tu marido te apoyaba.>> <<Pero mi suegra no. Mi suegra le buscó otra mujer y, pues, a mí me dejaron sin casa y con mis hijos.>> <<Y, ¿qué hiciste?>> <<Pues me dí cuenta que soy una mujer muy valiente, lo dejé, y saqué adelante a mis hijos. Lo he sufrido. Pero vale la pena.>> Porque, ya, a raíz de esa formación que ella tuvo, pero perdió su marido, ella ha salvado muchas vidas. Que es la partería. |

OLIVIA: Because one even said, the experience of a woman. Of a midwife. That when she began training, she say, “my husband gave me permission,” right? “My husband supported me. But my mother-in-law didn’t like it. And she found him another woman. She put her [the other woman] in my house.” So [clears throat] when she talked to me and I said, “How?” I said to her, “but your husband supported you.” “But my mother-in-law didn’t. My mother-in-law found him another woman and, well, they left me without a home and with my children.” “So what did you do?” “Well, I realized that I am a very brave woman, I left him, and did the best for my children. I have suffered. But it is worth it.” Because, now, as a result of the training she had, though she lost her husband, she has saved many lives. Which is what midwifery is. |

The story of the doula, as Olivia relates it, encompasses the deep tensions these women face between gaining educational training and capacity building in exchange, many times, for potentially deep disturbances to their home lives. Moreover, when these women challenge the patriarchal values and practices of their communities, even with support from their husbands, it is sometimes other women who are the reinforcers of that patriarchy. This is particularly painful for women organizers and trainers like Olivia, who want to support women’s desires to gain new skills and knowledge, knowing that the price they pay may be enormous.

What follows is a contrasting anecdote—the women in our workshops finding solidarity and bonds through our collaborative theater work.

Scene 2: “Si realmente tejéramos estas redes” / “If we actually wove these webs”

Lights up, Women stand in a circle.

Now that we are back as a group, in the Spider Web, let’s share our favorite part of the event.

CYNTHIA: El trabajo de mujeres juntas . . . no solo en el tema del agua, sino también como mujeres, y si realmente tejiéramos estas redes de manera efectiva, cuánto podríamos lograr, ¿no? Porque, si nos damos cuenta, estas so las redes que tejen los hombres. Y para ellos, pues, les es más fácil poder salir al ámbito público y estar . . . en política, decisiones, este, de nuestra comunidad. Y si nosotras, este, realmente tejáramos estas redes y jaláramos parejo y sin aflojarle, creo que pudiéramos hacer cosas muy buenas. |

CYNTHIA: Women’s work together . . . not just on the topic of water, but also as women, if we really weave these sorts of webs effectively, how much could we achieve, right? Because, if we realize it, these are the webs that men weave. And for them, well, it’s easier to be able to go out in public and to be . . . in politics, making decisions for our community. And if we really wove these webs and if we pulled each of us evenly without letting go, I think we could do very good things. |

OLIVIA: … y como decía Cynthia, por lo regular estas redes las tejen los hombres. Pero también hay muchas mujeres que tejen. Y las mujeres no solo tejen; bordamos, costuramos, algo que rompen los hombres lo reparamos nosotras, sinceramente. Entonces, creo que es como el momento de nosotras ir, pues, tejiendo todo esto y armando una red entre mujeres. |

OLIVIA: … and as Cynthia was saying, usually these webs are woven by men. But many women also weave. And women don’t just weave; we embroider, we sew. If a man breaks (rips) something we repair it, honestly. So, I think that this is like the moment for us to go and, well, weave all of that and build a web between women. |

Scene 3: “Esa Chispa” / “That Spark”: Love and Laughter—Trust, Connection, Confianza

And, on a lighter note, this work is FUN—something that is often overlooked! This work can sound so boring on paper, but it’s fun. Something that has struck me and encouraged me through the process of reviewing and analyzing data are all the moments of extreme joy, happiness, laughter. This laughter helps us cope with difficult topics, it warms us up to each other and to the task of doing the theater work.

The women in the circle laugh.

CITLALLI: … esa chispa. Alegría. ¿De qué? Bueno, a lo mejor al principio, sí, esa pena. Pero, ya que están como en confianza, el hecho que se estén riendo, y eso, que estén muy en confianza. |

CITLALLI: … that spark. Happiness. From what? Well, maybe, at first, yes, that shyness. But, now that you (the women) are in confidence, the fact that you are laughing, and that. That you are very much in confidence (trust with each other). |

Everyone laughs.

Tanta risa! | So much laughter!

Laughter continues until lights go down.

This photo is a still shot from a 16-second video of this group assembling their tableau. In it, Martina (second from the right in white and black striped shirt) is explaining how, as a young girl, she fell into her family’s water tank and that her grandmother, when going to the tank to collect water with a small bucket, found her. Citlalli and Cynthia join her in laughing at the absurd idea of her grandmother reaching in with her small bowl and scooping a young Mujer Brigadista 4 out of the water tank, as Mujer Brigadista 4 herself plays her grandmother.

Figure 7: Diosas Citlalli Group laughing. Audio by Carolina Osorio Gil.

Finding humor in a potentially scary memory-turned-story like this facilitates a safe discursive space in which to explore and entertain different, and sometimes silly, outcomes. Moreover, practicing collaborative exploration and play has implications for doing similar work in relation to developing collaborative plans for water care and governance across villages. Laughing together as a creative team allows for trust to be quickly established among colaboradoras. Sharing a laugh helps us be en confianza to do this future water work.

Lights up on CARO, ERIKA, OLIVIA, CITLALLI in the car.

Todo nos fué muy bien aunque hubieron muchas sorpresas hoy! | Everything went really well even though there were many surprises today!

Si— | Yes—

Estuvo muy bonito todo. | It was all very nice.

A mi también me encantó aunque me hubiera gustado tener mas tiempo juntas. ¡Las vamos a extrañar! | I also loved it, although I would have liked to have spent more time together. We will miss all of you!

Lights down on Stage Left.

This reminds me of something bell hooks says about excitement in our work.

It is rare that any professor, no matter how eloquent a lecturer, can generate through his or her actions enough excitement to create an exciting classroom. Excitement is generated through collaborative effort (1994, 8).

In other words, excitement is not something an instructor, or, in this case researcher or workshop leader, can generate single-handedly—it must be done with and around others.

Lights down. Backdrop lights up, showing “An Ode to Laughter: A Collage.”

ACT III

Scene 1: “Entre puras mujeres” / “Amidst strictly women”: The Value of Creating Women’s Spaces for Knowledge Sharing and Collaborative Water Work

Lights up. Women stand in a circle.

In general, a typical capacity-building or empowerment workshop does not result in this level of meaningful connection and trust because typical workshops are hierarchical—with the facilitator, more like an instructor, coming in assuming to be the “expert” who is relaying information and knowledge onto the participants, who are typically observed passively sitting and receiving this knowledge. And, thus, knowledge and information only flows one way. Furthermore, in this hierarchical model of capacity-building community development workshops, the facilitators never have to reveal anything about themselves—they are not considered “participants” in the experience. Practicing these types of collaborative, nonhierarchical story-based arts interventions allows for deeper connections between participants, and between participants and facilitators, which in turn leads to richer collaboration in creating solutions to community needs that are centered around the participants. This work is also generative—cocreating new ideas and solutions together.

CYNTHIA: Yo creo también que hay, este, un contexto de puras mujeres les dió también la libertad de ellas desenvolverse totalmente como ellas son. |

CYNTHIA: I also think that, well, a context of women only also gave them a freedom for them to feel comfortable to be themselves. |

MUJER BRIGADISTA 1: Nos escucharon cada historia. Yo escuché y me escucharon a mí. |

WOMAN BRIGADIER 1: Each of our stories was heard. I listened, and I was listened to. |

These testimonios, one from a facilitator (Cynthia) and one from a participant (Mujer Brigadista), both touch upon the climate of deep listening and deep understanding that led the women to feel safe to share their experiences. Feeling listened to and appreciated helps us be comfortable sharing more. Sharing a story and then watching it get acted out—get treated with care and attention to honor our experience—is a transformative experience that also is generative; it fosters the sharing of even more (her)stories and experiences. Moreover, it leads to the cocreation of possible futurities.

Typically, if you or I (an outsider such as a government official or a workshop leader) go into one of these communities of Berriozábal, as we learned from the interviews with Olivia, Citlalli, and Cynthia, we will hear from the men, not the women. These very same women who, in the course of a three-hour workshop, shared their fears and traumas around the river, laughing as they co-constructed the frozen scenes—these same women who laughed and joked easily while eating sandwiches during the lunch break—these women are typically unheard in a public format. Meanwhile, these women are the ones who hold significant water knowledge in their communities. They are the ones who use the water for cooking, for bathing children, for washing clothes; who know what the most efficient ways are for reusing the water; who walk to the river with young children in tow to collect water when needed. As they reveal in the informal interviews after both workshops, they are the ones who know when the water delivery comes to the communities that purchase tanks of water. However, when it comes to governing and standing as official water officers for their communities, it is the men who take these roles.

When we create women-only spaces for “puras mujeres,” we make space for these women to “desenvolverse,” to feel comfortable enough to share their unique and valuable knowledges.

Scene 2: Testimonios de Mujeres / Testimonies from Women

Díganme, por favor, ¿cómo les pareció el taller? ¿Creen que les ayudará con su trabajo de Brigadistas? | Please tell me what you thought about the workshop. Do you think it will help you for your work with the Brigadistas?

MUJER BRIGADISTA 1, MUJER BRIGADISTA 4, and MUJER BRIGADISTA 5 are center stage. See Fig. 9 and click on Figure 8 to hear the audio of the following transcription.

Figure 8: Mujeres Brigadistas interview. Audio by Carolina Osorio Gil.

MUJER BRIGADISTA 5: En mi comunidad, bueno (apunta hacia MUJER BRIGADISTA 1), en nuestra comunidad (Tirol), que es la misma, nosotros acaparamos lo que es la lluvia. Ponemos canal a lo largo de las casas, de la lámina, y eso va directo al tanque, es un almacenamiento. No tenemos casi fuente. Tenemos un arroyito, perro es muy poco lo que nos bastese. Entonces nosotros ya tuvimos que, este, ingeniarlo, o las personas más grandes que nosotras, para tener nuestra propia agua que es lo que viene de la lluvia. |

WOMAN BRIGADIER 5: In my community, well (points to WOMAN BRIGADIER 1), in our community [Tirol], which is the same one, we catch rainwater. We installed a channel along the houses, made out of laminate composite, and that goes straight to the water tank, it’s a silo. We hardly have a spring. We have a small stream, but it yields us very little water. So, we had to, well, engineer it, or rather those elder than us, so that we [our community] could have our own water, which is what comes from the rain. |

MUJER BRIGADISTA 4: Sí, incluso al menos ellas tienen su almacenamiento, tienen un arroyito donde agarrar. Nada más en la comunidad de nosotros. Incluso, hay personas que no tienen donde almacenar agua. En el caso de nosotros, o sea cada quien, o sea, a costo de uno mismo se hace su almacenamiento. Nosotros si no tenemos, mas que todo, esperanzados al agua, pues, que llueva. |

WOMAN BRIGADIER 4: Yes, well at least they have a water tank, they have a small stream to collect water from. In our community we don’t have that. We even have people who don’t have anywhere to store the water. In our [community’s] case, each household is on their own, in other words, each household is responsible for the cost of their water storage tank. We don’t have one, we are mostly hopeful for the water, well, that it will rain. |

This interview transcript was provided, not for the purposes of analysis, but rather as an example of the deep sort of testimonio that was gained after spending several hours together, bonding and conviviendo through our theater experience. I cannot claim causation—i.e., I cannot definitively say that because we did this workshop, the women provided a more specific, higher quality response to their issues and knowledge about water in their communities. However, what I can testify to is that we did bond, and I visibly saw these very women go from being extremely quiet and soft-spoken in the beginning, to opening up and commenting on feeling comfortable at the end. Moreover, the organizers who came for the workshop (Olivia, Cynthia, and Citlalli) commented on how different this workshop was from other earlier training experiences they’d had with these same women.

Scene 3: Conclusion

Of course, it’s impossible for me to tell if the women opened up any more than they would have if we hadn’t done the workshop, but my experience teaching theater workshops to folks who are completely new to the process provides me the confidence to say that the entire air about the women changed noticeably from the beginning of the workshops to the end. Approaching the activities and the strangers cautiously at first, after experiencing some shared activities, laughing at many points throughout, the women looked much more comfortable by the end and were much more talkative with me, as well as with the other facilitators, in addition to with each other. I don’t think the level of detail and extensiveness of the conversation we present here would have been possible without these specific story-based theater workshops. These workshops provided a nurturing safe space for the Mujeres Brigadistas to feel held and heard.

For women, the need and desire to nurture each other is not pathological but redemptive, and it is within that knowledge that our real power is rediscovered. It is this real connection which is so feared by a patriarchal world. Only within a patriarchal structure is maternity the only social power open to women. Interdependency between women is the way to a freedom which allows the I to be, not in order to be used, but in order to be creative (2007, 111).

MUJER BRIGADISTA 4: Recordar, bueno, en este dado caso que recordamos nuestra historia antepasada, el como pudimos, este, volver a … como nos pudimos salvar de todo eso, ¿no? Y mas que nada, este, lo bonito es que compartimos nuestra historia y, bueno, pues, para nosotras en el taller ese lo que nos sirvió es poder convivir con las demás personas en cualquier lado. |

WOMAN BRIGADIER 4: To remember, in this specific case, that we remembered our past story, how we could, well, once again… how we could save ourselves from all of that, right? And more than anything, well, how beautiful it is to share our story and, well, for us the workshop helps us in that we can convivir together with other people in any place. |

MUJER BRIGADISTA 5: Pues sí, la mera verdad, pues. Irnos familiarizando mas, ¿verdad? Y poner en practica en nuestras vidas más que nada. |

WOMAN BRIGADIER 5: Well, yes, the truth is, well, that we are becoming familiar with each other more, right? And to put [what we learned] into practice more than anything. |

MUJER BRIGADISTA 1: Podemos cuidar el agua para no causar, pues, problemas con el agua. Tomamos agua que no nos … no nos conviene, pues, para el estómago. No nos da buena salud ¿verdad? |

WOMAN BRIGADIER 1: We can take care of the water so as not to cause, well, problems with the water. We drink water that doesn’t … doesn’t benefit us, for our stomachs. It doesn’t bring us good health, right? |

AUTHOR & CARO (AUTHOR speaks to Audience while CARO speaks to MUJERES BRIGADISTAS, but they speak in unison): Gracias por su tiempo. | Thank you for your time.

END

Acknowledgements

- Debra Castillo

- Erika Díaz Pascacio

- Olivia Hernández Gómez

- Citlalli Ventura

- Cynthia Ortiz

- Tomasa (Mujer Brigadista)

- Gladis (Mujer Brigadista)

Notes

1 This piece, based on my master’s thesis (in progress), entitled “Entre Puras Mujeres / Among Strictly Women: Applied Theater, Community Building & Women’s Water Knowledges in Chiapas, Mexico,” is written in the form of an interactive script. Imagine that the photos are projected on a screen or characters on a stage, click the links to feel yourself immersed in this theatrical performance. After all, academic articles are performative by convention. This script is written as an experiment in form and contains some aspects that might not actually be able to be carried out in the sense that a traditional script is—it contains some creative (im)possibilities. I take inspiration for this script from two pieces, each about a woman “split” into two characters: Dolores Prida’s (1991) play Coser y Cantar and bell hooks’s chapter entitled “Paulo Freire” in Teaching to Transgress (1994). I am grateful to my friend and mentor Prof. Debra Castillo for her invaluable input on this piece.

2 Women Brigadiers, the name for the participants of the workshops.

Work Cited

Anzaldúa, Gloria. 2012. Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. 4th ed. San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books.

Boal, Augusto. 1985. Theatre of the Oppressed. New York: Theatre Communications Group.

2002. Games for Actors and Non-Actors. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge.

Cornwall, Andrea, and Jenny Edwards, eds. 2014. Feminisms, Empowerment and Development: Changing Women’s Lives. London: Zed Books.

Davis, Lizzy Cooper. 2019. “The Free Southern Theater’s Story Circle Process.” In Creating Space for Democracy: A Primer on Dialogue and Deliberation in Higher Education, edited by Nicholas V. Longo and Timothy J. Shaffer, 128‒139. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing.

Freire, Paulo. 2013. Education for Critical Consciousness. New York: Bloomsbury.

2015. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

hooks, bell. 1994. “Paulo Freire.” In Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom, 45‒58. New York: Routledge.

Lorde, Audre. 2007. “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House.” In Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches, 110‒113. Berkeley, CA: Crossing Press.

Prida, Dolores. 1991. Coser y Cantar. In Beautiful Señoritas & Other Plays. Houston: Arte Publico Press.

Sandoval, Chela. 2000. Methodology of the Oppressed. Theory Out of Bounds 18. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Trinidad Galván, Ruth. 2015. Women Who Stay Behind: Pedagogies of Survival in Rural Transmigrant Mexico. Tucson: The University of Arizona Press.

Villenas, Sofia A. 2005. “Latina Literacies in Convivencia: Communal Spaces of Teaching and Learning.” Anthropology & Education Quarterly 36 (3): 273–277.