Abstract

This reportage—essay, on—site sketch, and photos—centers around an interview with Paulina López, one of the leaders working toward the cleanup of the Duwamish River Superfund site in the South Park neighborhood of Seattle. The conversation and the experience of the place expands the idea of “river” to include efforts at community “placekeeping,” environmental justice, and climate resilience.As you walk toward the Duwamish River in the South Park neighborhood of Seattle, tractor trailers fight for space in the street next to the park, their roars competing with jets descending toward SeaTac. You skirt the chain link fence, careful not to get caught in the blackberry bramble, and drop down the bank to the black sand. It’s low tide, and your tracks sink deeper as you approach the water. You notice tracks of skunks and racoons and Canada geese, the weedy species that thrive in these niches that don’t look much like habitat. Alaska, Southwest, Delta. You try not to look up at every plane, but you do.

This isn’t an easy river to get to or even be aware of as you work your way through industrial parks and neighborhoods. The front yards of bungalows have just enough space for swing sets and fall-wilted kitchen gardens. On the main streets, the coffee shops and gentrifying pubs jostle with tire shops, taquerias, and boat repair shops. Warehouses, such as the enormous Boeing B-10 building across the Duwamish from the park, line up along both banks upstream and down. When you try to get close to the water, sometimes you find concertina wire lining the fences and streets dead ending where hoisting cranes and skip loaders move pipe and metal parts onto barges. You avoid looking at the white light of a welder’s torch making two things one.

And then you turn a corner and find this pocket park, a concession to the idea of a community, the merest suggestion that the river serves needs other than transport and disposal. Standing next to the water feels cathartic, but you start to think about what you cannot see: PCBs, dioxins, arsenic, and cancer-causing polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (CPAHs) (USEPA 2014, 39).

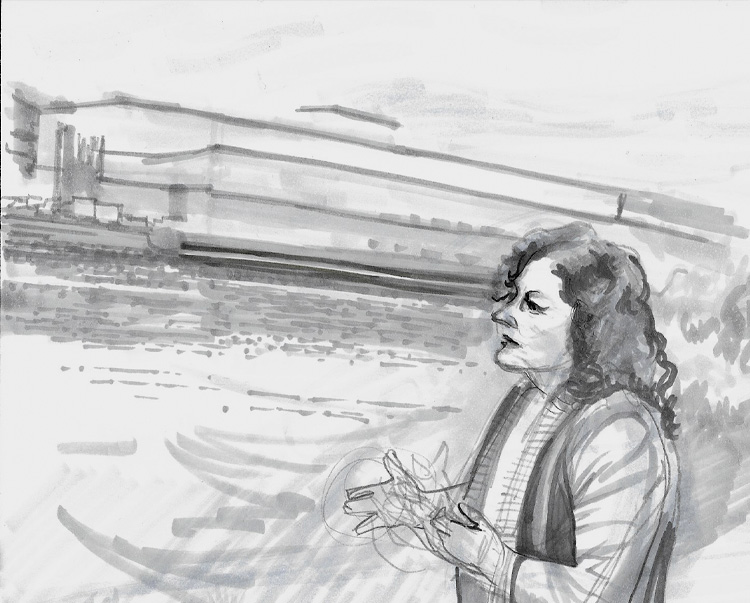

Paulina López, the person Amiko and I are here to talk with, is good at seeing the unseen, which is what you have to do to fight against the erasure and voicelessness of the river and its communities. She knows that a river is not just the water—it’s the sedimented stories of people past and present, layers of surface and subsurface meaning, sometimes churned up in a swirling current of material agency and cultural meaning.

As Executive Director of the Duwamish River Community Coalition, López works to make sure the layers of toxicity do not become the only story the river tells. Renaming itself so that “community” replaces “cleanup,” DRCC celebrated its 20th anniversary by orienting its storytelling even more toward the future. López and others amplify the voices of local communities so that they can lead decisions about their own resilient future, even in the face of threats like climate change. But it’s not easy to do that in one of the least visible and geographically isolated neighborhoods in Seattle.

When we meet in the park, López is in the midst of a pushback against a betrayal by politicians and officials who lobbied the EPA behind the scenes to raise the levels of allowable toxicity in the Duwamish, thereby lessening their cost and responsibility for cleaning the river as mandated in the EPA’s Record of Decision in 2014. Their back-channel strategy ignores the communities that have worked for decades to achieve a plan that makes the river safer for everyone. “It’s a slap in the face,” says López, “because they are not considering cumulative impacts. It’s not just about the cancer-causing chemicals in the sediment. I’m also breathing polluted air, I also don’t have access to open space, and I also don’t have the same amount of supermarkets with healthy food, and my kids have the highest asthma rates in Seattle” (López 2021). Indeed, a 2022 study published by the American Chemical Society documents how redlining and discriminatory mortgage practices map directly to present-day racial disparity in exposure to air pollution. Along the Duwamish, communities such as South Park and Georgetown fit this pattern.

The EPA’s application of a national standard ignores the cumulative effects of injustice born by the neighborhood and endorses the kind of violence that’s slow, that doesn’t make headlines. This violence occurs gradually but with devastating effects on individuals and on the community’s dream of resilience and connection.

After the lower Duwamish River was named a Superfund site by the EPA in 2001, cleanup began at the Early Action Areas, one of which was the Boeing plant across the river from the park where we talk with López. This initial cleanup was sometimes conducted with a lack of care and expertise that redistributed toxic sediments and required continual independent oversight by groups like Puget Soundkeeper Alliance and DRCC (Cummings 2020, 131). This was about the time that López arrived in Seattle from Ecuador to further her education after working with Indigenous communities to resist extractive economies. In Ecuador, she identified with the 1200 mountains and the rivers, and in South Park, “I fell in love with the river,” she says. “I wanted to live in a place where I felt at home, where I could see people who looked like me, and where I could hear my language being spoken.”

Somehow, the idea of a living river at the heart of a community allows for the existence of a coalition of Indigenous water protectors and recent immigrants who arrive with something other than a settler-colonial mindset. López points out that many of the people who live in the neighborhood arrive with an understanding of Indigenous identity. “They’re coming from native communities in Guatemala, in Mexico, and El Salvador,” she says, “and they have found that there is so much commonality.” López describes how, when she initially got involved with river advocacy, local tribal leaders made a point of telling her what they knew about Indigenous communities in Ecuador. “That was, to me, a very special moment that really brought out the importance of the legacy that they are building and what they are trying to accomplish through the cleanup and better stewardship of the land.”

The continual struggle against erasure feels familiar from the perspective of the Duwamish, a treaty-signing tribe that is not federally recognized. James Rasmussen, DRCC Superfund Manager and longtime Duwamish Tribal Council member, tells the story in a video interview on Indigenous Peoples’ Day. Officials at the end of the Clinton administration signed all the necessary documents to grant tribal status to the Duwamish (Thrush 2007, 196). Then, after George W. Bush was inaugurated, nearby tribal governments lobbied intensely and the official recognition was overturned, leaving the Duwamish enmeshed in a long-running legal struggle. At the same time, there is a continual effort to remain present in the minds of Seattle residents in a city much given to evocations of Indigenous past. One of these efforts, the Real Rent Duwamish campaign, gives Seattle residents the chance to put dollars behind verbal land acknowledgements. In response, the Muckleshoot tribe continues to oppose Duwamish recognition and insists on (re)defining local tribal identity as solely theirs. In the optics of White Supremacy, everyone has to fight for the wavelength of allowable Indigenous visibility.

Downstream of South Park, past cement plants and near the massive port complex, one of the last remaining meanders of the original river bends around Kellogg Island at həʔapus Village Park and Shoreline Habitat (formerly Terminal 107 Park) across West Marginal Way from the Duwamish Longhouse. The park exists because sharp-eyed observers saw the Port of Seattle excavating archaeological sites and got court orders to stop the digging. Cormorants rest on the pylons in the water where the Muckleshoot set nets to exercise their federally recognized treaty rights to fish for salmon. If you arrive at low tide, you can step down the cut bank to the sand and look back to see the midden, sedimented layers of shells tossed aside after dinners long ago, evocative trash from centuries of Indigenous presence. It’s tempting to suggest that the midden, nearly lost to industrial development, embodies the attempted erasure of history, sovereignty, and culture over the last couple hundred years. But its survival also helps you to imagine a place in the present with fewer broken ties, with more visible and vocal connections between past, present, and future, between human communities at odds with each other, between river species and humans, between what’s in and on the water and everything that flows into it.

In mid-October, it’s the tail end of the fall salmon run, but there are still some coho swimming upstream toward spawning grounds, and there are still some people fishing, which raises questions about the safety of cultural practices that tie people to the river. López explains, “When we have our immigrant and refugee communities come to the river, they really don’t believe that it’s contaminated. If you’ve been in other rivers in the world, you can smell, you can see pollution.” But in the Duwamish, the toxins are in the sediment, so the salmon are the only fish that’s safe to eat because they are transitory in the river. The resident fish and shellfish are unsafe, having bioaccumulated contaminants. Signs in many local languages explaining the hazards at fishing sites along the river don’t stop locals from fishing recreationally and for subsistence. In the Vietnamese community especially, López points out, it’s part of their heritage. Grandparents teach their grandkids to fish.

River contamination, then, as well as declining numbers of salmon for Indigenous subsistence and ceremonial use, becomes a driver of cultural decline. “For us,” says López, “it’s very important that they are well informed so they can make the decision about what they are fishing.” But what does it mean to see a sign saying that to enact a crucial part of your identity could be deadly? What are you willing to risk?

Yet the cleanup, too, has its risks and challenges. If a cleaner, healthier river with more open spaces leads to higher property values, how do you ensure that the people who have suffered decades of harm benefit from the improvements and economic opportunities? López and DRCC use the word “placekeeping” to encompass their antidisplacement efforts to resist gentrification. Their term riffs on “placemaking,” which the Project for Public Spaces describes as an idea and process to “reimagine and reinvent public spaces as the heart of every community.” Yet “placemaking” is often used by developers in branding that implies authenticity. “Placekeeping,” in contrast, suggests the tenacity South Park and other Duwamish River communities will need to hold on to their homes. “We need affordable housing and better jobs, green jobs, that allow people to stay engaged in their community,” says López. “We keep acknowledging climate resilience and building community capacity because we see this as a great way to let people thrive.”

After our interview and reportage sketch of López, a Filipino fisherman arrives at the park and casts a spinning rod into the river. “I’m on a three-week dry spell,” he says, “but I’ve stood right here and watched Chinook swim. This long.” He holds out his arms, a mug of coffee in one hand. He’s carrying three rods, each rigged differently. One with a jigger and squid-like hootchi, one with a spinner, and one with a buzz bomb. He casts out and reels in, casts out and reels in. “Oh, I know about the toxic,” he says. “I would eat them from here or maybe a little further up, but it’s better to catch them closer to the ocean. They’re so good.”

I ask López about hope and hopelessness, and her conversation keeps coming back to the youth. Her work in the neighborhood began when she established the Duwamish Valley Youth Corps, focused on environmental justice and developing youth leadership. Among many projects, the youth have planted 1500 trees throughout South Park and Georgetown. López says, “They come up to me and say, ‘Paulina, every time I see the tree I planted I’m glad because I know my sister will breathe better air.’ They understand a sense of the connections.”

Connection and community ownership are high on the list of values López hopes to nurture in younger people in her neighborhood, and it’s clear that her sense of future possibilities rests on a genuine sense of trust in the next generations. “They’re making the changes, so they can see the future,” she says.

I remember how, when she arrived at the interview in the park and saw Amiko’s sketch pad, pencils, and pens, the first thing she did by way of introduction was to pull out her phone to share animations done by her tech-precocious 13-year-old son. The animations made visible river issues and calls for change in ways that seemed part of his generation, his way of processing the world. As I recalled her pride in her son’s achievement, I began to understand that her motivation as an activist was not so much to impart wisdom or to mentor youth as it was to create conditions where their own wisdom could manifest. She trusts the youth like she trusts the authentic voices of the community to grasp the reality of the situation, in all its complexity and profound challenges, and then to respond in ways appropriate to their own perspectives.

If river toxicity and community pollution are a kind of intergenerational trauma, it makes sense to respond by cultivating future leadership through radical intergenerational trust and admiration.

Downstream from South Park, a concrete port control tower next to the Lower West Seattle Bridge bears a sign labelled “Duwamish Waterway,” the word “river” powerful in its absence. To name it a river would be to assent to the broader sense of community that “river” implies. Beneath the bridge, seals slap their tails as they fish for salmon then move to the edges of the river to make way for a tugboat spouting a plume of diesel particulate. After the boat passes by, the seals move back to the middle. The salmon stay deep, moving from cover to cover, invisibility in their case increasing their odds for survival.

Work Cited

Cummings, BJ. 2020. The River that Made Seattle: A Human and Natural History of the Duwamish. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

López, Paulina. 2021. Personal Interview with Paulina López. Interview by Brad Monsma.

Thrush, Coll. 2007. Native Seattle: Histories from the Crossing-Over Place. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

USEPA (United States Environmental Protection Agency). 2014. Record of Decision: Lower Duwamish Waterway Superfund Site. https://semspub.epa.gov/work/10/715975.pdf.