An Emerging Zeitgeist

Abstract

This paper—in the form of an image-rich slide show—traces the history of Water Art in New York City as a microcosm of the growth of artists making work in, on, and with water around the world. In presenting the development and growth of Works on Water (WoW)—an artist collective founded to support Water Art and artists—as well as discreet art historical precedents and influential movements, this paper offers a case study for how WoW has approached building a movement called Water Art in response to Land Art.2005 / Tide and Current Taxi

An image shows a young white woman with brown hair in a life jacket and black jeans, sitting on a red cushion in the bow of a homemade boat floating on the East River. The New York City skyline is ahead, as she looks over her shoulder at the camera, smiling, holding a red paddle. The caption of the image reads: “The currents were moving north quickly. It was the perfect time to take Melissa Brown to Manhattan to catch the Number 4 or 5 train to work” (Lorenz 2005).

This is one of the documented trips from 2005, the first year of the Tide and Current Taxi, by artist Marie Lorenz. A printmaker, Lorenz started making boats to explore the Providence, Rhode Island, waterways in art school. The Tide and Current Taxi—still in operation every summer—marks one of the earliest and longest artist works in and on the New York City waterways.

http://www.tideandcurrenttaxi.org/

2007 / Mare Liberum

In the foreground is a large piece of white vinyl that reads, “Material World.” It is an old billboard getting recycled into a boat. A white man in a blue shirt and gray pants and a woman in an orange sweater and gray skirt, both with dark hair, are on the ground next to the piece of vinyl, fastening it to a wooden frame. Behind them are two boats, both clad in colorful vinyl, and in the background is an unfinished wooden boat, resting upside down on two sawhorses.

Mare Liberum (The Free Seas), an art collective, formed in 2006 along the Brooklyn waterfront when founding members Stephan von Meuhlen, Ben Cohen, and Dylan Gauthier had access to a boat moored in the Gowanus Canal. At the time, the Brooklyn waterfront was mainly postindustrial and devoid of human activity except for its discarded construction materials and garbage, yet Mare Liberum recognized these waterways as places worthy of exploration and recreation. Through their extended experiences on the Gowanus Canal, the founding members began to translate and share their interest in building boats from found materials into workshops and broadsheets instructing others how to do the same.

2007 / High Water Line

A young white woman with a blonde-ish ponytail wearing a light-blue T-shirt, olive green clam-diggers, a black messenger bag slung across her chest and back, and black Converse high tops pushes a commercial-grade line marker. Underneath and behind it is a crisp pale blue line, several inches wide. The woman and the machine are moving across cobblestoned, potholed pavement that seems generations old. Late-colonial-style brick warehouses sit in the background as do a coffee cart selling coffee and bagels and a tree-filled park. At the entrance to the park are bikes locked to bike racks, a man drinking coffee, a do not enter sign, and a flagpole flying flags of the City of New York and the Parks and Recreation Department. In the far background, the iconic stone arches and latticed cabling of the Brooklyn Bridge rise up in front of the skyline of lower Manhattan.

Over the course of many months in 2007, Eve Mosher carefully walked through the boroughs of New York City to replicate the flood map, as it was drawn that year. A critical part of Mosher’s project, High Water Line, were the discussions that the artist had with viewers as she walked, which brought a new—and at times, shocking—awareness of the potential for flooding in one’s neighborhood and home. Mosher’s project predicted the flow of water and the harm that would come to the city in 2012 with Superstorm Sandy.

2009 / The Waterpod

A photograph of New York City’s East River, taken from high above, is framed by the roadways of the Brooklyn Bridge, the Manhattan Bridge, the eastern coast of Manhattan, and the western coast of Brooklyn. In the foreground is a large black barge labeled WEEKS, a two-tiered white and black tugboat attached. Several structures sit on the deck of the barge: a wooden shed with solar cells, and two geodesic domes—one clad in white waterproof material, the other unclad. There are people working, gardens, and other equipment on the barge.

The Waterpod, Mary Mattingly’s first monumental work in a series of large-scale explorations of waterborne self-sufficiency, was launched and toured New York City’s waterways in 2009. Mattingly and a crew of collaborators lived aboard The Waterpod to demonstrate the self-sufficiency of its systems. Inspired by the expensive cost of living, the freedom of the waterways, and increasing reports of sea level rise and climate change, The Waterpod anticipated the increased water and landscape changes in coastal cities a decade later.

2009 / Underwater New York

An ordered array of multicolored jugs, bottles, and pill containers fills the frame of the image. Many of the large jugs are yellow, and several of them are crumpled, or otherwise deflated and/or dirty. Others are black, orange, green, or blue and also crumpled and/or faded. Smaller bottles are also similarly colored in bright, yet sometimes faded, primary colors. This image is Oil, Drugs, and Alcohol (2010) by artist Barry Rosenthal and is part of Found in Nature, a series Rosenthal started in 2007 as a riff on his botanical prints, that evolved from miniature collections of found objects into large-scale images of ocean-borne garbage.

Underwater New York (UNY), a collective started by a group of writers inspired by a 2009 article about objects pulled from New York City’s waterways, has a mission “to help our audience envision New York City in a new way, through its sixth borough.” UNY has compiled thematic issues of writing and multimedia works, as well as hosted events and workshops since 2009. UNY began collaborating with WoW in 2018.

https://underwaternewyork.com/

2012 / The Bridge

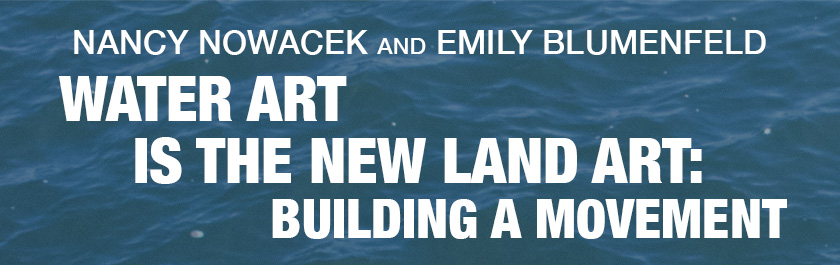

A photo of New York City’s Governors Island on a sunny summer day, captured from the middle of the East River, is overlaid with a digital rendering of a modular floating wooden walkway with orange metal handrails. A black and white image of a white woman with short dark hair, a dress, and sneakers, with a sweater tied around her waist, carrying a parcel, is collaged on top of the rendering as though she is on a slow, meandering walk across the river. She is walking the 1200 feet from Brooklyn across the East River to Governors Island.

The Bridge (formerly Citizen Bridge), by Nancy Nowacek, was a long-term speculative project weaving Brooklyn history, city politics, maritime policy, and advocacy for public access to New York City’s waterways into design prototypes for a floating walkway in commemoration of a long-gone sandbar between Brooklyn and Governors Island. This sandbar was traversed back and forth by Lenape peoples, Brooklyn settlers, and livestock at low tide. This rendering depicts one of eight designs prototyped and tested in city waterways between 2012 and 2015.

https://www.nancynowacek.com/the-bridge

2013 / 36.5, A Durational Performance with the Sea

A grid of nine images depicts the same scene of a waterway, a rock, a white woman with short brown hair standing in a red-orange long-sleeve sweater and blue jeans. She is standing on the right-hand side of the photo. Grasses line the foreground of the photo, and a stand of dark green coniferous trees lines the waterway in the upper-right-hand corner of the frame. The woman is fully visible, head to toe, and the waterway is shallow and muddy. Moving from the upper left to right, top to bottom, there is more water in each photo. In the middle photo of the grid, the water has risen to the woman’s neck. As the water recedes in the following four images, the day becomes night, and the woman’s full body becomes visible again.

This is the first performance of New York City artist Sarah Cameron Sunde’s 36.5, A Durational Performance with the Sea. This project is a poetic, elegiac, durational performance illustrating the visceral impact of sea level rise on a singular human body. Sunde went on to perform this work with local artists and inhabitants in coastal areas around the world and plans to finish the project in New York City in September of 2022.

2016 / Mapping Water Art

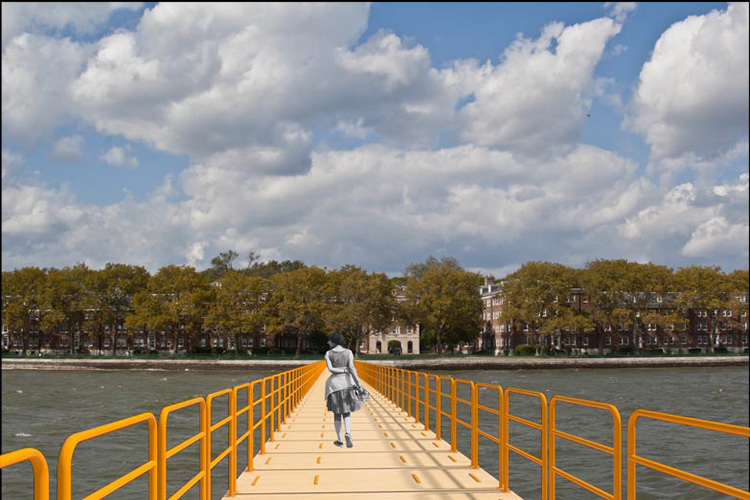

An uneven whorl of dots in the center of the image contains red, orange, blue, and green dots, unevenly organized and surrounded by a whorl of white dots. More red, blue, orange, and white dots are scattered around the outside. Dense hairline networks of lines in white, red, blue, orange, and green join the dots in different bundles and run off the page, somewhat like airline route maps. Clustered around the dots, in very small gray type, are the names of art projects like Wading Bridge, Wearing an Island, Swimming Cities of Serenissima, and Water Treatment Walks. At the left-hand bottom corner is a legend for the dots: red connotes Time, blue connotes Theme, Orange connotes Media, and green connotes Relationship to Water.

Artists Eve Mosher, Nancy Nowacek, and Sarah Cameron Sunde joined together to map the increasing frequency of new artist works in, on, and/or with water. Together, they created their working definition of Water Art: Art that uses water as site, material, or collaborator. To date, this map represents 206 Water Art projects from New York City and around the world.

https://www.worksonwater.org/relationship-map

Coalescing and Naming a Movement

Mosher, Nowacek, and Sunde were joined by Clarinda Mac Low, Katie Pearl, and Emily Blumenfeld, and their collective work became Works on Water in 2016. Works on Water formed with a mission “dedicated to working with water to bring new awareness to the public of the issues and conditions that impact their environment through art.... [It is dedicated] to artworks, performances, conversations, workshops and site-specific experiences that explore diverse artistic investigation of water in the urban environment. [It seeks] to strengthen and nourish the community of artists working on and with bodies of water and to provide a platform to increase awareness of artists and organizations working on and with the waterways.” (Works on Water 2018).

https://www.worksonwater.org/what-we-do

Works on Water’s first collective project was the planning and curation of the first art triennial dedicated to Water Art for summer 2017. The goal of the triennial was three-fold: to name Water Art as a new genre, to coalesce the community of local artists in New York City dedicated to Water Art, and to make Water Art—most often manifested in the water as an ephemeral event—visible to the art public, environmental advocates, and local government. Artists included in the gallery exhibition were Torkwase Dyson, Floating Studio for Dark Ecologies (Marina Zurkow, Rebecca Lieberman, and Nicholas Hubbard), Marie Lorenz, Mare Liberum, Mary Mattingly, Paloma McGregor, Eve Mosher, Nancy Nowacek, Sunk Shore (Clarinda Mac Low, Carolyn Hall, and Paul Benney), and Sarah Cameron Sunde. These artists were commissioned to transform their ephemeral water-based practices into dynamic gallery installations.

Works in the gallery space were complemented by Field Works—free programs and events open to the public around the city’s waterways. Field Works engaged over 3,000 audience members and participants. Programs and events were hosted and/or performed by 14 more artists and curators and included dance pieces, plein air painting, theater performances, walking tours, writing workshops, and conversations.

Works on Water, in partnership with New Georges and Guerilla Science, incorporated several theater works, science-based works, and public conversations into the triennial. To learn about the over 30 Water Art projects, events, and discussions featured in this first triennial, please see https://www.worksonwater.org/events/2021/3/25/2017-triennial-commissioned-works.

Movement building begins with a groundswell of recognition. In 2016, Radical Seafaring was mounted at the Parrish Art Museum on Long Island, 90 miles from Works on Water’s efforts in New York City (https://parrishart.org/exhibitions/radical-seafaring/). Curated by Andrea Grover, this exhibition included works by Mare Liberum, Mary Mattingly, and Marie Lorenz, as well as others from around the world, and articulated the increasing phenomenon of artists engaged with waterways and oceans.

2018–2022 / Building Community

A yellow-sided duplex sits behind a large leafy oak tree, surrounded by deep green grass. Printed lengths of fabric stream out of second-floor windows like waterfalls. Large paintings of overlooked marine species on vellum hang from the porch. People dressed for warm weather cluster in small groups, talking; a line of visitors waits to enter the house on the right. In the foreground is a folding table with hand sanitizer, face masks, and a clipboard. Works on Water celebrates its July 30th, 2021, installation of its 2020–2022 three-year triennial, on Governors Island in the WoWhaus.

Movements emerge from communities of shared practices. In 2018, Works on Water initiated a residency program to bring artists with similar urges and interests together by making space and opportunities for them on Governors Island. Governors Island is a historic island in the New York City harbor. Initially called Paggank by the Lenape, and then Nutten Island by the Dutch colonists, Governors Island was most recently the Northeast headquarters for the United States Coast Guard. When the island was transferred back from federal ownership to local ownership, the Coast Guard vacated the island and its small city of buildings. Works on Water’s residency was housed in one of the many former Coast Guard family homes offered by the Trust for Governors Island to arts organizations. Nicknamed the WoWhaus, the space welcomed over 100 artists over its four-year tenure. Works by Water Artists spanned all media—from painting and drawing, text-based to digital works, and performances—and, through the lens of the waterways, these works often intersected with history, science, culture, food, and politics.

The second Works on Water Triennial, slated for 2020, adapted to the uncertain timeline of the pandemic by transforming into a three-year exhibition. Planned programs suitable for virtual translation were held online, such as the WoW Video Show. The goal of this specific triennial component was to bring national and international Water Artists into WoW’s growing community. The context of the pandemic offered a unique opportunity to exhibit twice as many artworks from around the world—11 countries total—in virtual screenings on Zoom. Works were live streamed in thematic programs over three days and followed by artist discussions with the public about their works.

WoW’s three-year triennial continued in the summer of 2021, including two exhibitions on Governors Island. The second triennial continues through 2022, showing works by resident artists and members of its growing Water Art community. The framing of the second triennial Works on Water has begun to shape and articulate new definitions of what it means to make and exhibit contemporary art. The conditions under which Water Artworks are made are often antithetical to traditional studio practices, wherein artists labor singularly and in solitude. More and more, Water Artists in the WoW residency come together to collaborate on artworks that hybridize forms of sculpture, performance, and participation. As such, these works don’t live comfortably in the traditional art contexts of the gallery or museum. They need to live in public spaces, and oftentimes next to, if not in, the water. In this way,"showing" Water Art requires new definitions and exhibition practices.

This brief history of Works on Water and Water Art in New York City demonstrates the origin, definition, and nurturing of the Water Art Movement. The efforts of Works on Water are part of a global contemporary art movement shifting into the water. It is also the legacy of several historical art movements and key artworks.

Water Art Precedents

Artists have long investigated water’s materiality, its political influence, and its spiritual uses. See Charlotte Eyerman’s essay “Water & Power: A Brief Art History” in the Works on Water Inaugural Triennial catalog. (Eyerman 2018, 40–43).

The prehistory of Water Art connects representations of the landscape and monumental land art to more communal, caretaking, and politically and socially engaged practices that are integral to the emergence of Water Art.

We trace Water Art’s origins in America to the Hudson River School, whose pastoral visions contributed to the definition of the American identity. Countless Hudson River School paintings suggest a wild and rugged landscape tamed by the enduring strength and romanticism of the American spirit.

In 1941, Ansel Adams was commissioned by the National Park Service to capture images for a mural in D.C. about protected nature throughout the National Parks system in the US. Adams served as a member of the Sierra Club board for 37 years and used his photos of the American West to lobby for the formation of the National Parks and myriad conservation issues. Adams was a dedicated artist-activist, playing a seminal role in the growth of environmental consciousness in the US and the development of a citizen environmental movement.

1970 / Marking Water

This image is a photograph of reddish-colored water, into which a spiral path of basalt rocks has been built in rural Utah. In the middle of the path is a solitary figure, small against the stone- and waterscape.

Earth Art marked a turning point in modern art. It was the moment where minimalism left the gallery and ventured out into the landscape at scale. Works that were once limited by the volumes of the galleries and museums that exhibited them, once outside, could expand to a scale that matched their surroundings.

Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty is an emblematic work of the Land and Earth Art Movement. Smithson chose to make this work in the landscape to draw viewers’ attention to the power of nature. The journey to the artwork through the rural southwest was as much a part of the artwork as the jetty itself. Smithson intended to create a persistent but beguiling work: a permanent intervention into the natural landscape that might not always be visible, depending on climate conditions and water levels. Due to climate change, Smithson’s work—submerged for 30 years—has reappeared and is visible once again. Ironically, the water is no longer surrounding the work and the Jetty is firmly reclaimed by the land.

It is not a coincidence that Spiral Jetty was made during a time of civic change: civil rights, feminism, and environmentalism were burgeoning at the end of the sixties. As more works began appearing in the landscape, more artists began looking to the landscape as an artwork in and of itself.

1987 / Accessing Water

Artist Mary Miss, an older white woman with long brown hair twisted into a bun secured with a pin, dressed in black, stands on a waterfront walk with blue lanterns. To her left are trees and benches; to her right is a wooden railing and the New York City harbor with historic piers. In the distance, the walkway continues and reaches out over the water. In the far distance of the harbor are two sailboats and the Statue of Liberty. This photo was taken at Miss’s project Walk on Water, 1984–1987 in South Cove in Battery Park City (a coastal neighborhood in lower Manhattan) in June 2017. Miss is leading a tour, organized by Works on Water as part of its first Triennial, of the site she designed in 1987. South Cove was the first-of-its-kind design collaboration inviting New Yorkers to engage with the Hudson River.

Thirty years before the first Works on Water Triennial, Mary Miss collaborated with architect Stanton Eckstut and landscape architect Susan Child on the design of South Cove in Battery Park City. Walk on Water, 1984–1987 is a sculptural work over the water that invites South Cove visitors to the water, to hear its sounds, and to feel its embrace. It blends the hardscape of Battery Park City with the softscape of the water, creating a seamless engagement with the natural world in an urban context. https://bpca.ny.gov/place/south-cove/

The growing environmental movement and burgeoning awareness of climate change in the late eighties and early nineties called for more artists to protect and restore the natural world around them.

1991 / Curing Water

A white balding man in a white shirt is wading into the water. The water reaches up to his torso. His arms are outstretched, and he is releasing a large white disk made of limestone. The water is turbulent and frothy around him.

In 1983, Buster Simpson began his ongoing series, Antacid Purge, as a response or “cure” for rivers made sick by acid rain. His performance at the Hudson River headwaters became the most publicized of the performances and was exhibited by Barbara Matilsky, curator of Fragile Ecologies: Contemporary Artists' Interpretations and Solutions at the Queens Museum (1992). Simpson placed hand-carved limestone disks in polluted rivers in a performative attempt to neutralize their acidity. The rushing river water dissolves the limestone, a base that counteracts acid, to help clean the river. The exhibition included a short video of the performance that played in a continuous loop, highlighting the futility of the restorative gesture. http://www.bustersimpson.net/purgeseries/

The themes of protection and restoration from the early 1970s to the late 1990s evolved into sustainability at the turn of the millennium. City planners started to plan for and commission artists to conceptually engage with and aesthetically enhance water infrastructures in order to bring them into public consciousness and foster their stewardship. For example, the City of Calgary’s Utilities and Environmental Protection Department opted to pool their public art funds for the 2006–2010 capital infrastructure cycle because most of the capital spending would be buried underground. This fund was used for public art, design, and related educational programming that raised awareness of the watershed and citizens’ roles in its continued health. Given the scope and complexity of this opportunity, the public art program commissioned A Public Art Plan for the Expressive Potential of Water Utility Infrastructure (2007), the first public art plan focused specifically on water utilities.

Meanwhile, as the United States economy shifted from a manufacturing economy to an information economy, many urban cities were awash in abandoned post-industrial waterfront spaces. Artists such as Marie Lorenz and those mentioned at the beginning of this piece found these waterfront areas rich in inspiration.

From Land Art to Water Art

Recognizing the growing community of Water Artists in New York City and beyond, Mosher, Nowacek, and Sunde, wrote the criteria that qualify a work as Water Art.

WATER ART CRITERIA

The work must meet BOTH of the following conditions:

- The work self-defines, first and foremost, as art.

- A body (or bodies) of water is central to the work’s concept.

Additionally, the work recognizes that water is alive and dynamic, and therefore experiential rather than representational. It must meet at least ONE of the following conditions:

- If object-based, a body of water (and/or its shorelines) is used as MATERIAL in the physical production of the work.

- If time-based, a body of water (and/or its shorelines) is the SITE for the work, functioning as a “stage” and/or central “character” that embodies the temporality and/or spatiality of the work.

Their work was motivated by the assertion, "Water Art is the new Land Art.” Land Art was a practice of making marks directly in the landscape, though it remained tied to the gallery system through notions of "Site" and "Non-Site.“ Land Art tended to be singular in its conception and creation.

By contrast, Water Art is collaborative and conceived through a sense of community urgency, care, and connectedness in the context of an environment in need of repair. Water Artists work as advocates to increase civic awareness by engaging in discussions with planners, scientists, politicians, and government agencies. Water Artists bring focus to the waterways as places of discovery, knowledge, and future empowerment.

As referenced in Sarah Cameron Sunde’s essay, “Environmental Art for the 21st Century,” in the Works on Water Triennial catalog, “underlying these criteria is the idea that Water Art is a direct descendent of Land Art”; Sunde goes on to say, “while the monumental interventions of land artists marked the earth, shaping it for generations to come, the large-scale conceptual works of water artists acknowledge urgency in the time-scale. The execution of the works is more ephemeral—happening over the course of a day or a month or an hour, often shifting human consciousness around the water on a person-to-person scale” (Sunde 2018, 7–9).

This contemporary movement has taken hold in part by the recognition that water is a necessarily collaborative space and material. Not only have artists joined together in community, but they are building cross-sector partnerships with others dedicated to building environmental advocacy in response to the increasing urgency of climate change. Building a movement of Water Art in a city defined by complex policies and regulations requires government partnerships. In recognition of the shared mission of their work to increase public advocacy for the waterfront and waterways, WoW started a partnership with the New York City Department of City Planning (NYC DCP), one of the 13 agencies with jurisdiction over the 520 miles of waterways.

Works on Water invited the Waterfront and Open Spaces division of the NYC DCP to be Planners in Residence in the WoWhaus on Governors Island in 2019. Their first shared project was working together to expand the Department’s skills and strategies for public outreach. Waterfront Planning Camp emerged as a day-long event facilitated by Works on Water community artists, planners, and representatives from other city agencies for members of the public to engage in activities ranging from making go bags for flood preparedness to boat tours and waterways bingo, and to share their ideas for the future of the city’s diverse waterfront.

The partnership between WoW and NYC DCP that started in 2019 continues. It has taken multiple forms, all of which have been focused on increasing public awareness of, interest in, and advocacy for the city’s 520 miles of waterways and waterfront. Through these projects, Works on Water commissioned 36 Water Artists to create artworks, public prompts, and/or public interventions.

2021 / WoW Hydrofesto

In building a movement, Works on Water first started by recognizing the growing urge of local artists to engage with their waterways, and then gathered together those artists into a triennial exhibition. The first WoW Triennial served as a public framework to define Water Art. With framework and definition in hand, WoW’s second goal was to grow the community of Water Artists in New York City and beyond. Lastly, a critical component to building the Water Art movement continues to be cross-disciplinary partnerships, engaging intersectionality of water as a historic, political, social, cultural, and economic space.

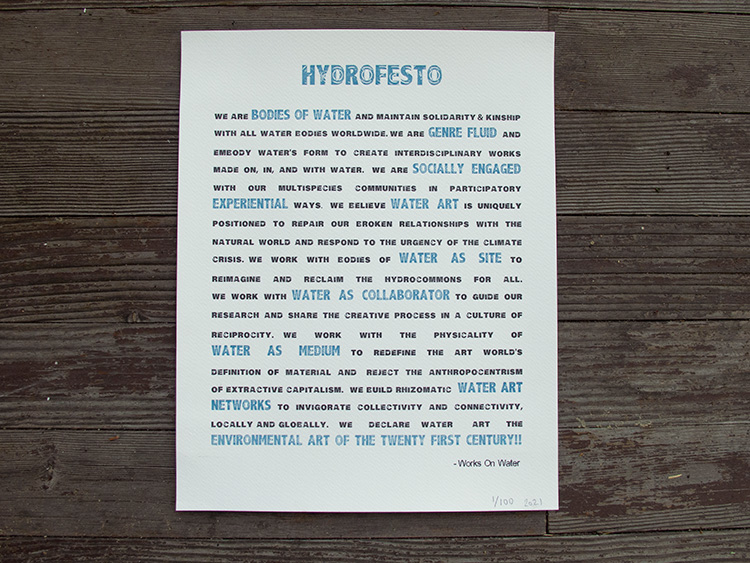

The Works on Water Hydrofesto, initiated and designed by sTo Len and Sarah Cameron Sunde, expresses WoW’s guiding values and serves as an open invitation to join the community and the Water Art movement.

The Hydrofesto is a letterpress print in black and light-blue ink on cream-colored paper, on weathered wood flooring. The text is set justified across the page and is titled "Hydrofesto" in light blue all caps with circular white lines like water ripples running through the word. It reads:

We are bodies of water and maintain solidarity & kinship with all water bodies worldwide. We are genre fluid and embody water’s form to create interdisciplinary works made on, in, and with water. We are socially engaged with our multispecies communities in participatory experiential ways. We believe water art is uniquely positioned to repair our broken relationships with the natural world and respond to the urgency of the climate crisis. We work with bodies of water as site to reimagine and reclaim the hydrocommons for all. We work with water as collaborator to guide our research and share the creative process in a culture of reciprocity. We work with the physicality of water as medium to redefine the art world’s definition of material and reject the anthropocentrism of extractive capitalism. We build rhizomatic water art networks to invigorate collectivity and connectivity, locally and globally. We declare water art the environmental art of the twenty first century!!

https://www.worksonwater.org/hydrofesto

Work Cited

Eyerman, Charlotte. 2018. “Water & Power: A Brief Art History.” In Works on Water Inaugural Triennial, 40–43. New York: Works on Water.

Grover, Andrea, curator. 2016. Radical Seafaring, exhibit at the Parrish Art Museum, May 8–July 24, 2016. https://parrishart.org/exhibitions/radical-seafaring/.

Lorenz, Marie. 2005. Melissa Brown Goes to Work. http://www.tideandcurrenttaxi.org/.

Matilsky, Barbara. 1992. Fragile Ecologies: Contemporary Artists' Interpretations and Solutions. New York: Queens Museum of Art and Rizzoli International.

Sunde, Sarah Cameron. 2018. “Environmental Art for the 21st Century.” In Works on Water Inaugural Triennial, 6–9. New York: Works on Water.

Utilities and Environmental Protection Department, City of Calgary. 2007. A Public Art Plan for the Expressive Potential of Utility Infrastructure. Prepared by Via Partnership, Cliff Garten Studio with CH2M HILL.

Works on Water. 2018. “Mission.” https://www.worksonwater.org/what-we-do.