Abstract

As an artist who collaborates with scientists, how can I help make visible the visceral sense of loss caused by glaciers melting due to climate disruption and simultaneously promote a positive action? Ice Receding/Books Reseeding emphasizes the necessity of communal effort, scientific knowledge, and artistic expression to focus on the complex issues of watershed restoration by releasing seed-laden ephemeral ice sculptures into rivers with the help of local communities. As the frozen volumes float downstream and melt, the native seeds, selected in consultation with stream ecologists and botanists, are released and begin to plant themselves along riverbanks. This project presents a lyrical way to promote positive actions in helping restore streams anywhere in the world. My riparian projects are not about theorizing while sitting in an armchair or classroom, but rather about connecting directly, and in physical ways, with the river.As an artist who collaborates with scientists, how can I help make visible the visceral sense of loss caused by glaciers melting due to climate disruption and simultaneously promote a positive action?

Ice Receding/Books Reseeding emphasizes the necessity of communal effort, scientific knowledge, and artistic expression to focus on the complex issues of climate disruption and watershed restoration by releasing seed-laden ephemeral ice sculptures into rivers. With the help of local communities, the Ice Books are placed into the water. Each launch of the ice sculptures is an energized gathering of participants, many of whom have not physically been to their river before the event. The project provides a hands-on educational experience by encouraging interaction with the waterway. As the frozen volumes float downstream and melt, the native seeds, selected in consultation with stream ecologists and botanists, are released and begin to plant themselves along riverbanks. This project presents a lyrical way to promote positive actions in helping restore streams anywhere in the world. My riparian projects are not about theorizing while sitting in an armchair or classroom, but rather about connecting directly, and in physical ways, with the river.

Part of the significance of the Ice Books is that they melt away. They are impermanent. The ways of knowing later about an ephemeral object or event is through documentation, which might be writing, filming, photographing, and drawing—or all of these. In the documentary film Ice Receding/Books Reseeding, we see Ice Books being launched into rivers around the world. The film was begun in 2007 and is updated as new projects occur. When I had my large retrospective exhibition in the Netherlands, 2015–2016, an entire gallery was devoted to photographs of the Ice Books.

The Ice Books are replicable, ephemeral, only leave behind native plants, bring together local diverse communities, use nontoxic materials, have little to do with the commercial "art" world, and can be created by multigenerational age groups. References to timely ideas are alluded to through the sculptural form of the book.

These impermanent sculptural tomes are vehicles for change that have been seen on the Big Wood River in Idaho, inscribed with wild iris and wild rose seeds; in Paris, overlooking the Canal St. Martin, as an oblong book containing maple (Acer sp.) seed sentences; and in Arles, France, with lavender (Lavandula allardii) sentences. A frozen volume laden with snowberries (Symphoricarpos albus) and another with red elderberries (Sambucus racemosa) ride the milky glacier melt of the Nisqually River in Washington State. A small, carved book with wild fennel (Foeniculum vulgare) paragraphs meanders slowly along the Muga River, Spain, in view of the Mediterranean, its destination.

Stream ecologists, river restoration biologists, and botanists help to ascertain the best seeds for each specific riparian zone. The seeds form a language of the river, a restoration text. The calligraphic sentences of seeds slide from the melting pages of the translucent volumes into the water to be carried to shore. That a tiny, quiet bundle can transform into some enormous cottonwood tree or tiny fragrant lily of the valley or thorny cactus is wondrous. An individual seed is a spectacular sculptural display, with each one being elegantly and distinctively formed. For example, the long, narrow seed of the mountain mahogany (Cercocarpus montanus) is a small hairy helicopter, with a pointed end that corkscrews in spirals into dry desert soil whenever it rains.

Plants sequester carbon, mitigate floods and drought, pollinate other plants, disperse seeds, create soil regeneration and preservation, act as filters for pollutants and debris, supply leaf litter (for food and habitat), promote aesthetic pleasure, hold the banks in place (to slow erosion), and provide shelter/shade for riverside organisms, including humans.

Since 2007, I have created several hundred of these time-based sculptural Ice Books for global rivers. Those who contribute to or participate in the Ice Book launches are from the local communities where I am honored to be invited. Along the Nisqually River in Washington State, for example, Nisqually Tribal Members, salmon restoration specialists, musicians, fifth graders attending Wa He Lut Indian School, students and professors from Evergreen State College, forest rangers, all took part. We also gathered community volunteers to help plant trees along the river to hold the banks in place and provide habitat.

Participants in New Mexico on the Río Grande have included artists, farmers, acequia majordomos, hydrologists, filmmakers, physicians, University of New Mexico students and professors, Pueblo members, and hundreds of interested watershed citizens. The Albuquerque Museum hired two city buses to transport people to the site where the Ice Books would be launched.

There were nine different departments and institutes at Antioch College and the University of Dayton that invited me to create an Ice Book project in Ohio. This included the Rivers Institute and even the physics department. When it came time to place the books into the Miami River, instead of launching the dozen sculptures from shore, we attached them to the front of a flotilla of kayaks and paddled them out into the current to be released. Along the banks, 100 participants lifted glasses of drinking water toward the river and proposed a toast: “May you always flow and may you always flow clean.” The Rivers Institute still corresponds with me and each year teaches their students about the importance of the Ice Book project for helping to promote riparian health.

I really enjoyed creating Ice Books with students, faculty, and members of the Swampy Cree Tribe when invited by the University of Saskatchewan to work alongside the Saskatchewan River Delta. Faculty in the Art Department and the Biology Department continue to lecture about our experiences in the Delta region, collaborating with the Swampy Cree Tribe.

Deckers Creek, West Virginia, is highly polluted with acid mine drainage that turns the water a sickening shade of orange. I worked closely with members of the Friends of Deckers Creek, and we decided instead of using seeds, the Ice Books would be embedded with limestone “words” that help to balance the pH level in the creek. A professor from the University of West Virginia donned hip waders so that she could safely place an Ice Book into the water. To participate in the Ice Book projects, you have to physically be at the river and interact with others. Being aware of the plight of flowing water that is always asked to give more than it has, is a call for action.

More recently, I have been working with people from around the world who want to create their own Ice Books to make connections to their watersheds and initiate restorative actions that address local ecological issues. The results have been inventive, educational, and inspiring, with examples coming in from Hawaii, Spain, France, the Netherlands, Canada, and Mexico.

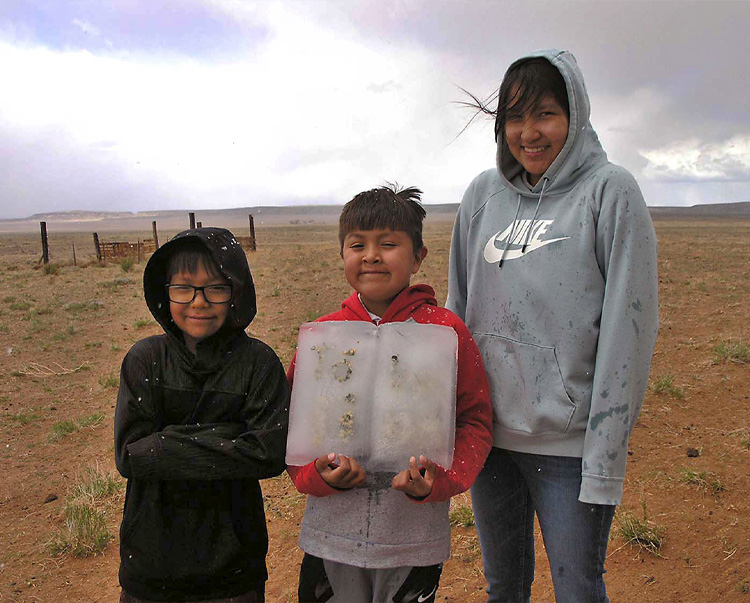

A professor in China organized a three-day workshop with adults and children who launched the Ice Books into the confluence of the Jialing and Yangtze Rivers. An Ice Book in England focuses on species loss and the collapse of amphibian populations. A frozen volume in Sydney, Australia, is embedded with mangrove seedlings. A Navajo artist carved the words for “Water Is Life” (Tó bee iiná) in his native Diné language and planted sacred corn within the text. The book was planted in the red desert earth of the Navajo Nation where there is no river, and the corn began to grow as tall as the artist’s three children.

Most recently, I was invited to represent the United States in a Biennale in Ecuador, curated by Blanca de la Torre, from Spain. Because I was unable to visit Ecuador, a sculptor was hired. I sent directions to him about how to carve a 100-pound Ice Book. We worked with a local botanist in Cuenca to find the best Indigenous seeds which were embedded into the ice and placed to melt in the garden near the museum. Four Ice Books were created, each representing one of the four major rivers flowing through the region.

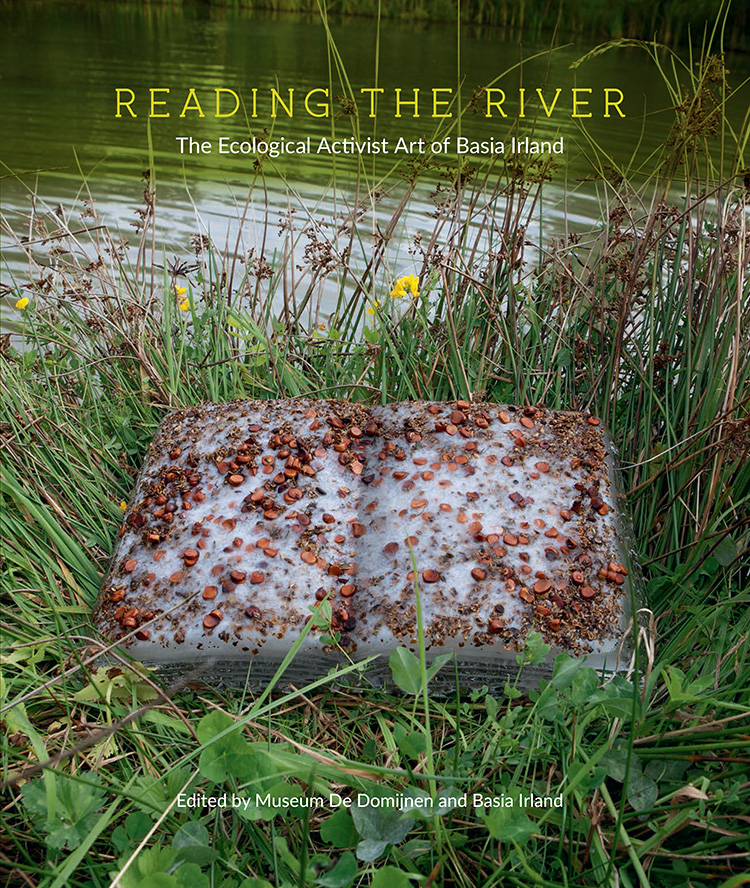

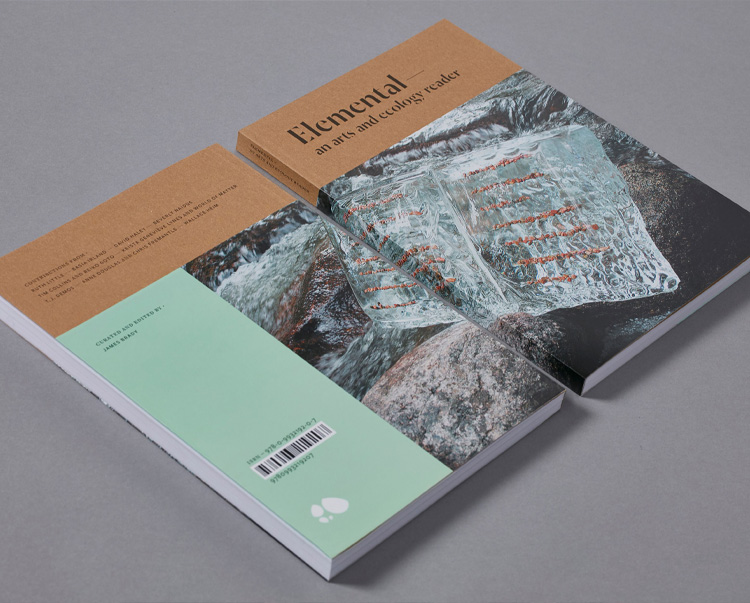

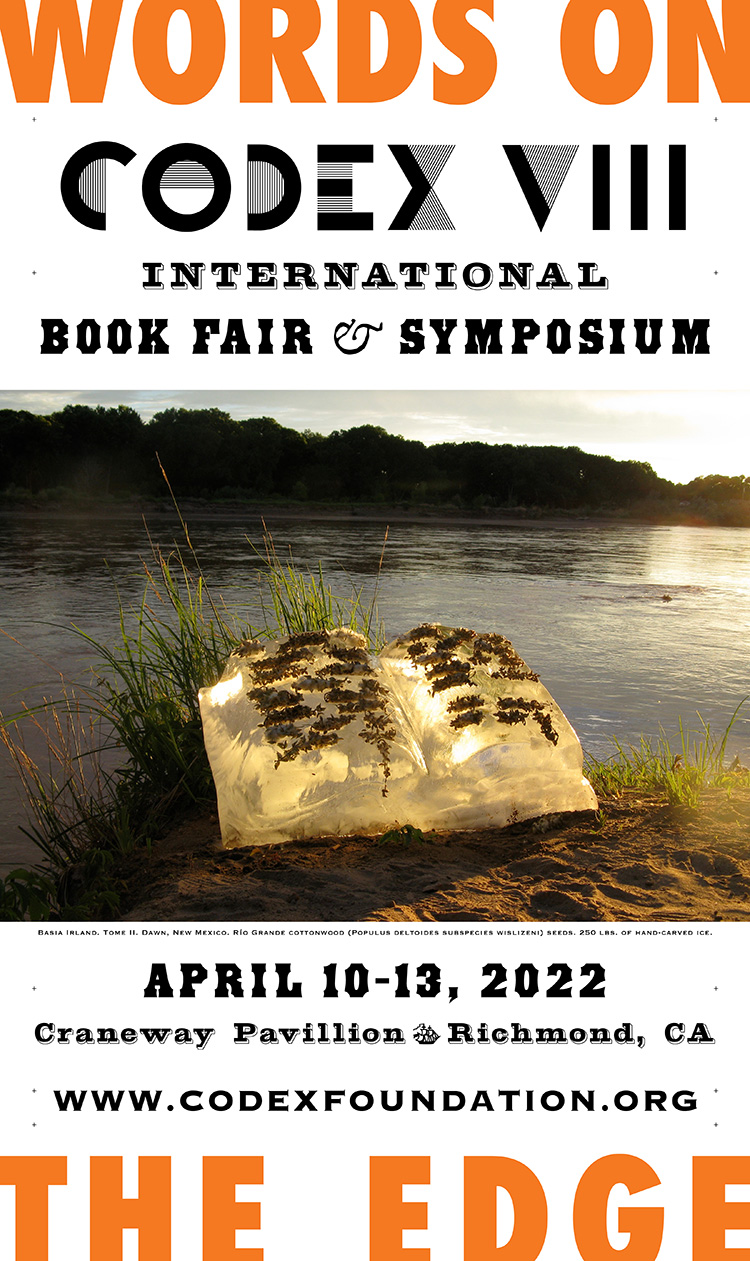

Images of the Ice Books have been used on book covers and posters. A few examples include the cover for my 2017 book, Reading the River: the Ecological Activist Art of Basia Irland, which was published in conjunction with my retrospective at the Museum de Domijnen, the Netherlands; Elemental: An Arts and Ecology Reader, 2016, edited by James Brady and published by Gaia Project Press, UK; and Count, a book-length poem about the climate crisis by Valerie Martinez, 2021, University of Arizona Press. In April 2022, the Codex Foundation asked permission to use an image of one of my Ice Books for a poster for the International Book Fair, “Words on the Edge.” The caption reads, “Basia Irland. Tome II. Dawn, New Mexico. Río Grande cottonwood (Populus deltoides subspecies wislizeni) seeds. 250 lbs. of hand-carved ice.”

Each of us is a walking river, sloshing along—damp insides held together by paper-thin skin. We ARE water. Our bodies are circulating streams of sweat, blood, tears, urine. Water enters, circulates within us, and leaves. Everything is connected through a cycle. We flush our pee down the toilet, which goes to the sewage treatment plant, which flows into the river, which then, again, often provides our drinking water, as well as being evaporated into clouds of rain.

Rivers are alive. They have a body called a watershed, with a mouth at the delta; organs of wetlands and riparian zones; cells, molecules of water; and like us, a circulatory system. We are not separate from the waters of the world. We each have an external watershed. Mine is the Río Grande in New Mexico. But we also have an internal watershed composed of bodily fluids.

Like us, rivers become sick, which is to our detriment since we physically need clean water to survive. Sometimes the sickness is visible, such as when a river becomes a dumping ground. Other times the river’s illness can’t be seen, but tests reveal waterborne diseases only visible through a microscope. Do you know where your drinking water comes from? And what will a microscope reveal about what you pour into your personal watershed? How must we respect and take care of these flowing streams of water, which are so deeply connected to our own bodies? It is urgent that we have clean, fresh water. We simply cannot exist without it.

For me, an important aspect of a community-based ethic is gifting. The participants have donated their time, energy, ideas, and enthusiasm to each Ice Book project, so it is with great joy that I give back by presenting each person with a gift related specifically to the river where we have all worked together. Reciprocity. Biodegradable envelopes are filled with regional seeds so the recipient can continue the planting process and become involved with the river through caregiving. Also included are small watershed maps, lists of the seeds, and water websites. Working with community members is complex, yet it is continuously rewarding. It provides a basis for cooperation, dialogue, and sharing information and inspiration.

Being aware of the plight of flowing water, which is always asked to give more than it has, is a call for action. In this radically interconnected world, it becomes our collective responsibility to compassionately take care of each other and our environment and ensure that future generations will have enough clean water to survive and thrive.

I hope each of you will find ways to spend time with your waterway and get to know it intimately. If you visit your local river today, what would you add to an Ice Book to bring attention to ecological issues faced by your watershed?