Rootedness Facing Colonial Conditions:

Nourishing Hope, Accountability, and Orientation

Abstract

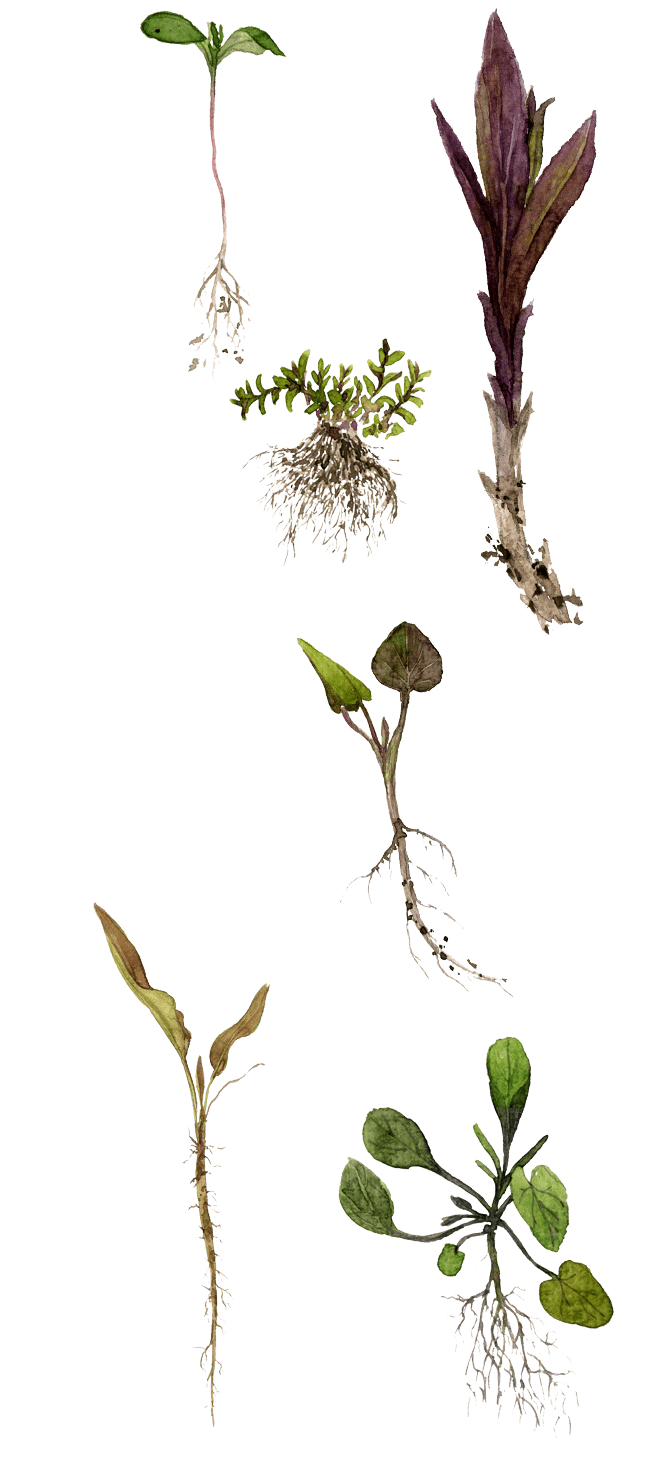

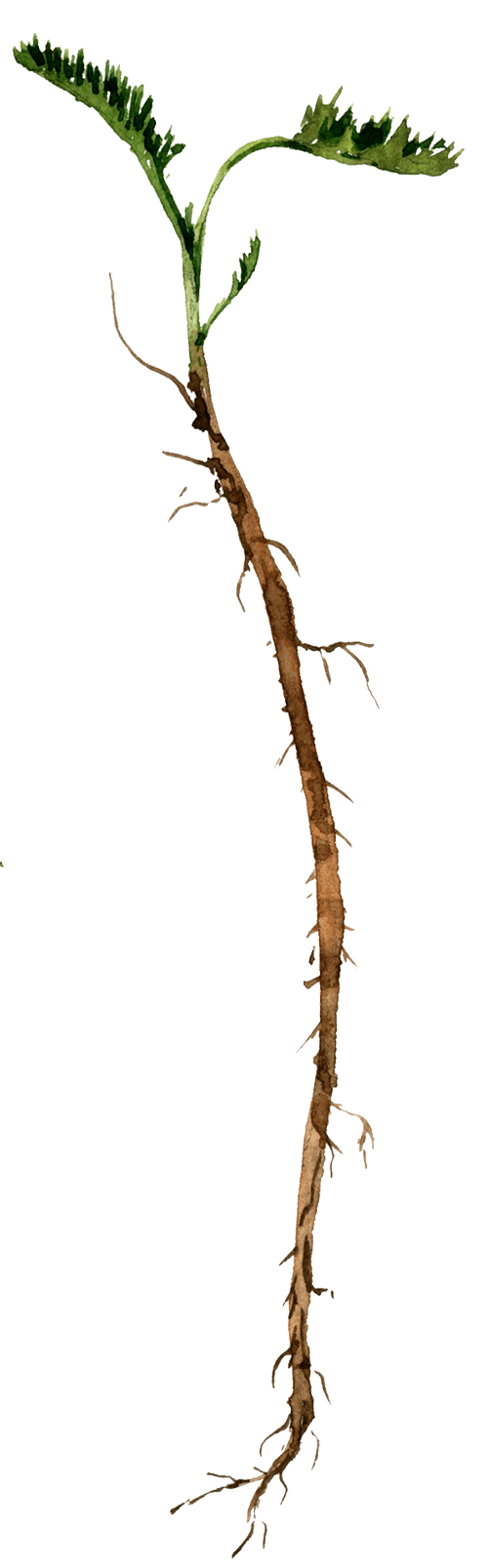

In the field of urban community food systems, the origin of the word radical in rootedness is often discussed. And in an era of climate catastrophe, pandemic, and widespread protests for civil rights, radical, rooted-in-place hope is both necessary and privileged, requiring hopers to orient themselves to their collective goals and social context, especially important in places with histories of colonialism, with associated expropriation of land and labor. Considering radical hope in a settler colonial context consequently makes me consider what it takes to know when to put down roots and, conversely, when to pull them up. If settler identity is good for anything introspective, it seems, it should be an acknowledgement and awareness of the privilege of rootedness, and the unevenness with which this privilege is distributed. In this essay, I consider the relationship between hope and rootedness, and the accountability toward which shared educational experiences can orient people as they consider how to face the future, and how to live well in social relationships. Hope requires a certain level of grounding to be realistic and not delusional. And sometimes practicing hope requires you to look hard at things you don’t want to do anymore, and figure out whether the time for those things is done and the roots should be pulled up, and perhaps put down in some other domain that needs new roots.

Lester looks out across the crumpled tin fence: I used to ride farm to farm … and I’d look out across the hills, the karris [eucalypts], the farms and dead crops, and you know the whole flamin country looked sad. All the plants with their heads bowed looking really browned off. And you know, I used to hear it moan. Not the wind; the ground, the land. I told meself it was the horse, but inside I knew it was the country, moanin. … You think maybe we don’t belong here, like we’re out of our depth, out of our country?

We don’t belong anywhere. When I was a girl I had this strong feeling that I didn’t belong anywhere, not in my body, not on the land. It was in my head, what I thought and dreamt, what I believed, Lester, that’s where I belonged, that was my country. That was the final line of defence in the war. …[but] I’ve been losin the war. I’ve lost me bearings.

Lester makes his teeth meet at all points round his jaw. Talk like this makes him nervous. Something’s going to happen, to be taken from him, to be shone in his face. It’s like walking down a rocky path at night, not knowing where it’ll lead, when it’ll drop from beneath your feet, what it’ll cost to come back.

But you will pardon me if I talk frankly to you. The tragedy is not that things are broken. The tragedy is that they are not mended again. The white man has broken the tribe. And it is my belief -- and again I ask your pardon -- that it cannot be mended again. But the house that is broken, and the man that falls apart when the house is broken, these are the tragic things. That is why children break the law, and old white people are robbed and beaten.

He passed his hand across his brow.

—It suited the white man to break the tribe, he continued gravely. But it has not suited him to build something in the place of what is broken. I have pondered this for many hours, and I must speak it, for it is the truth for me. They are not all so. There are some white men who give their lives to build up what is broken.

—But they are not enough, he said. They are afraid, this is the truth. It is fear that rules this land.

In the field of urban community food systems, the origin of the word radical in rootedness is often discussed. The play on words in the title and content of the forthcoming local film Radical Roots: The Story of a Food Revolution is an illustrative example. And in an era of climate catastrophe, pandemic, and widespread protests for civil rights, radical, rooted-in-place hope is both necessary and privileged, requiring hopers to orient themselves to their collective goals and social context, especially important in places with histories of colonialism, with associated expropriation of land and labor. Considering radical hope in a settler colonial context consequently makes me consider what it takes to know when to put down roots and, conversely, when to pull them up. If settler identity is good for anything introspective, it seems, it should be an acknowledgement and awareness of the privilege of rootedness, and the unevenness with which this privilege is distributed. In this essay, I consider the relationship between hope and rootedness, and the accountability toward which shared educational experiences can orient people as they consider how to face the future, and how to live well in social relationships. Hope requires a certain level of grounding to be realistic and not delusional. And sometimes practicing hope requires you to look hard at things you don’t want to do anymore, and figure out whether the time for those things is done and the roots should be pulled up, and perhaps put down in some other domain that needs new roots.

I encounter many people who have profoundly given up on humanity—even before they were required to inhabit the uncertainty of the extended crises of pandemic and civil unrest. I also encounter many people for whom rootedness has never been an option. The two colonial literary treatments of this condition used as epigraphs above evoke disorientation in country in a way that is often glossed over in environmental literature. Settler colonialism, however, is crucial to understand—including in our lived experience—in order to address the social and environmental conditions it has produced. The turn in climate justice toward the centrality of justice is helping contemporary environmental education articulate new commitments to disrupt the reproduction of colonizing. This lens helps us evaluate where to root, and where not to. The contexts of higher education and public teaching—the kind of community-engaged learning, research, and practice across boundaries emphasized in this journal—provide important venues for grappling with the kind of orientation we need to offer if we want people to be able to understand how they are accountable for the conditions of coloniality in which we find ourselves, and what we can do about it.

Wilting, the Possibility of Hope, and Mechanisms for Maintaining Staying Power

It’s not that people are giving up just out of exhaustion, despair, or a lack of being adequately rooted. Students in the classes I teach and members of the public who show up at community learning and organizing events are wilting in significant part because they are being asked to grapple with crushing problems of social inequality and climate justice while they are also facing increasing community and personal precarity and fragility. The range and scope of the destabilizing forces facing students, for example, are daunting. In the few years that Public has been published (since Cadieux 2013a), the percentage of Pell-eligible students at small liberal arts colleges such as the one where I teach has over tripled, adding paralyzing indebtedness for students and their families to the already overwhelming challenges of the university years (Fry and Cilluffo 2019). This means that our efforts to cultivate the radical hope needed for staying power in the fight against social and climate crises are coupled with literal nourishment efforts as we figure out how students can feed each other enough to learn (Feed Your Brain 2019), and as mutual aid hubs and care networks are built up (mutualaidhub.org). The unignorable vulnerability of this moment is rapidly teaching us how to embrace the desirability of addressing and not suppressing our shared experiences of this vulnerability. As many thinkers inveigling us against false hope argue (Jensen 2006, Cuarón et al. 2007), the processes of acknowledging and working through these challenges are crucial for grounding realist hope.

As an environmental studies professor and public artist, I have experienced the need to build platforms that support hope both in order to preserve mental health in myself and the students in my classes, and also to engage wide public audiences in the public art projects I have carried out in the past five years. Higher education and community economic development, especially in the realm of earth’s “critical zone” work, are important domains for recognizing that as people have decreasing resource access while they are also coming to terms with the scope of the troubles they’re dealing with, they may not really have a substantive basis for hope. Consequently, platforms for nourishing hope need to go beyond invoking hope as an aspiration or transient mood—or false belief in being saved—to hope as a long-term strategy that can be propagated, shared, maintained, and turned into nourishment (notably, these metaphors are not about hope being “discovered,” or “built” from scratch, as these ideas tend to undervalue collaborative maintenance work in favor of individual innovation). In the realms of community food, this nourishment is material and also spiritual and affective. Emotional nourishment is important for engaging in feminist and postcolonial praxis, recognizing and acknowledging the emotional labor that goes into community organizing, and the kind of participatory action research and learning we are often doing when we engage our classmates and neighbors in conversations about how we might make the best of the climate crisis, or how we commit to mending what we do not have the cultural competency to keep, or to keep from breaking (Canty 2016).

Hope is also a necessary feature of the affective hospitality offered by effective institutions of learning—even if higher ed administration is not necessarily known for reinforcing the possibility of hope in its operations. However, when we treat our relatives as if we do not need to repair problems in how we are getting along, that is a betrayal of hope, and an acknowledgement that we cannot truly imagine moving toward the future together. I name here two dispositions that undergird the rest of this essay and that can be particularly helpful in countering this tendency for hope to wilt: (1) belief in the future and the capacity of learning, and (2) the constant embodied experience of interdependency. In the communities where I work—notably, in the neighborhoods around the school where I teach, where residents asked me to come work to help to support an institutional hospitality that would encourage their relatives to want to come to learn—people remind each other to come back to these dispositions repeatedly via what they call “call-in” culture.

Practicing call-in culture means we get to be supported by our relatives who might share valuable different perspectives and additional things to try, or ways to be in relationship, and we get to share our efforts with others. It also means we do not only model despair, frustration, and urgent fragility for those learning. In order to be hospitable enough to be willing to call each other in, and not just call out, it helps to recognize that we are all related—and in turn, repeatedly calling each other in to relational accountability helps us learn how we do relate to each other, and how we can relate to each other. Learning institutions make excellent case studies for the possibility of hope—and its wilting, as everyone who has gravitated to such a place has a tremendous amount to offer—and most have been over-hospitably willing to offer more than they can replenish, in the harsh collision between the monastic gift economy of traditional education and the neoliberal factory model of the consumer-based school. Radical hope provides people the space to share, along with the encouragement to be willing to ask for and gracefully receive help to figure out which of our goals can be flexible enough to receive offers of participation available from others. And we need to practice calling each other in when such calls are needed, whether because we are not stepping up, or because we need to be hugged in tight to a relationship in order to see the effects of our actions on it. Learning institutions have the potential to offer learners the supports to shape the transformed social relationships we hope for, but those of us who constitute learning institutions are relevant to learners’ learning only if we can be in relationship—with them, and with each other.

In order to highlight some features of how people can nourish radical hope, I draw here on one public art project and one course I teach at Hamline University—both of which, in turn, draw on many parallel projects and classes of mine and others’, and both focus on making the best of the climate crisis. I explore what distinguishes radical hope from superficial promises of hope that aren’t accessible to many of those who most need grounding, nourishment, and truly transformative interventions. The Planetary Home Care Manual course and the Making the Best of It: Dandelion project characterize a significant turn in my teaching and public work toward the centrality of communication about emotional experience. While felt experience has always been part of my work (Cadieux 2013b, 2016), it has usually had a subsidiary role, supporting the substantive content of the scholarship, pedagogy, or public engagement. After twenty years teaching university students, though, I felt challenged to reconsider how I was conducting orientation to the core issues at hand. Explicitly addressing how to access, build, and maintain hope and accountability seemed more vital to foreground, particularly after the difficult season of 2016, when half of the students, even in my most engaged courses, would regularly bail on class because of paralyzing anxiety and depression, and when campus and public divides in who was willing to talk about what became more starkly visible.

Project Manuals as Toolkits for Orientation

Making the Best of It: Dandelion was a three-year public art collaboration with Marina Zurkow and other artists and community members, particularly Sarah Petersen, Sassi Libertus, Aaron Marx, and a creative and dedicated crew of guides and helpers who showed up to lead others through the public installation spaces, based on their own interpretations of the project, and guided by a “dandyzine” pocket project manual. As one of the headline projects of two subsequent years of the Twin Cities’ largest all-night public art festival, Northern Spark (and as a regional installation of Zurkow’s broader Making the Best of It series), Making the Best of It: Dandelion was designed as a pop-up snack shed using the idea of eating indicator species as a way to move people beyond the usual ways of thinking about climate change and environmental guilt and paralysis (Cadieux, Zurkow, Libertus 2019). Some of the crucial mechanics of the project involved violating normal boundaries—both physical boundaries, with people putting dandelion-derived foods into each other’s mouths, as well as the affective boundaries between guilt and shame and grief and joy—and inviting these emotions to mix together and be used to relax into and send deeper roots into the question of how we can make the best of it. This question was layered to include acknowledgement that we’ve already messed up our chances at climate change mitigation, that recovery and reconciliation are impossible, and embracing mitigation and adaption is necessary, and that creating a social domain in which their embrace is socially acceptable is possible—with an explicit violation of the usual assumption that humans will be okay. With the playful and sometimes satirical assumption that humans have not made it in the envisioned scenario of climate change, the project performance emphasized that humans were still worth celebrating and making meaning around, even in their absence, as other entities figure out how to make the best of what they’ve left behind. Further project details and illustrations can be found in the Cadieux, Zurkow, Libertus (2019) article; the core project mechanic I’d like to highlight here was the use of project zines as manuals for orienting project collaborators and encouraging them to use the project from their own perspectives.

The Dandezine, courtesy Valentine Cadieux

Click to view full document.

Before discussing the “dandyzines” in more detail, I will briefly describe the Planetary Home Care Manual course I have taught for the past two years at Hamline University, influenced in many ways by the prior three years of working on the Dandelion project as well as by a shift in students’ interests. As Alison Spodek Keimowitz describes beautifully in her 2018 Slate essay on hope despite despair, teaching Environmental Studies under conditions of climate crisis and settler colonialism unavoidably highlights anxiety, guilt, anger, and despair. Addressing these emotions requires work beyond informing and inspiring students to be the environmental leaders we need. A significant shift was needed to keep them in class and not add further to their already heavy mental health burdens—a challenge only exacerbated by COVID and the murder of George Floyd, with its aftermath that torched significant parts of our campus neighborhood. After years of trying to balance coverage of an adequately comprehensive review of environmental and social systems to enable basic literacy in the introductory sequence for Environmental Studies with exploration of how various societies and social groups do succeed in collaborating to manage commons, fix problems, and maintain socio-spatial relationships equitably and with attention to care and repair, I finally succumbed to the need for an additional term. This allowed me to introduce a companion to the introductory course, intended to focus on successful examples of environmental stewardship, and engage students in building collaborative and systemic skills to imagine what it would take to live on earth for a long future—and to engage others in the required maintenance work. Called the Planetary Home Care Manual to invoke these learning goals explicitly, the course was set up to push back against student preference for fixating on environmental problems as mostly a result of information deficit. I attempted to shift the usual trajectory by replacing the usual format of assignments that lead to informative pamphlets, speeches, and posters frustratingly devoid of acknowledgement of the systemic reasons for the problems being addressed with prompts for alternate projects designed more explicitly as toolkits meant to collaboratively engage audiences in transforming the status quo.

To see the course assignments for the Planetary Home Care Manual, click here.

Santa Fe Art Institute Platform: Art & Social Engagement, Feb 22, 2019

Part of what quickly convinced me that this toolkit approach was worthwhile for teaching was its relative success in engaging audiences in exploring what else might be needed to understand a problem well enough to transform it. Charged with the task of orienting others, participants in both the Dandelion project and the Planetary Care course jumped vigorously into the process of filling in what they knew—and what they didn’t. Encouraging a focus on low-stakes, zine-like instruction kits helped participants to fixate less on the formalities of didactic knowledge sharing, and opened up more space for questions, uncertainty, and exploration of the real barriers to engagement, which were often emotional and systemic. Although I had to let go of many of my content-specific aspirations to give students more time to reflect on some very basic affective experiential barriers they realized they were facing, the resulting kits were much more amenable to progressive alignment with social, political, and economic contexts—engagement with which had often been frustratingly shallow in prior courses and public teaching. Small successes moving beyond the environmental studies of the head also seemed to convince students and public participants that beliefs, attitudes, behaviors, values, and emotions were better engaged than avoided (Throop 2016, Canty 2016). And projects such as a guide to asking for emotional help (a tissue box kit with student- and faculty-facing sides, offering guiding prompts for proceeding through fraught emotional territory with consent and assurance of mutual participation) and a guide for remaining comfortable when allowing oneself to possibly get lost (a box for snacks, a journal prepopulated with prompts for reflection, and a place to put away a phone) helped reframe some of the basic conditions of the current university generation more hopefully: instead of seeing how little any of them had practiced reorienting when lost merely in terms of a remedial skill lost to the availability of mobile phones in their experience to date, they could recognize this as a new skill to practice, and a domain for more explicit discussion with elders. Bringing the emotional work of such a daring endeavor as being willing to become lost on the way somewhere, or to sit outside against a tree with eyes closed (two of the most spontaneously replicated manual exercises of the course to date) brought emotional challenges more straightforwardly into the domain of the classroom, where they could be explored, shared, and addressed collaboratively. Further, this shift in normalizing consideration of emotional work also built a vocabulary and experiential toolkit for discussing coloniality.

The Getting Lost toolkit, courtesy Valentine Cadieux

Click to visit course website.

Orientation to the colonial conditions under which we live has become a central theme of my work for multiple reasons. These seem worth sharing here because the pathways by which these conditions moved from unnoticeable or unspeakable to a regular part of addressing topics like rootedness or hope help illustrate shifts we might all want to consider encouraging. The crises of 2020 have made these conditions more visible, too, and more people are able to see the need for decolonization and also to realize that they need to build literacy to participate in collaborative action. I came to understand myself to have inadequate literacy about colonial conditions repeatedly over the course of my education, and in progressively more profound ways. It is relevant, for example, that it is only in retrospect that I am able to interpret many experiences of my youth in significantly French Canadian regions of the United States in terms of intersectional identity. For example, the remedial French class into which I was placed in my first year of high school (my only experience of explicitly tracked education) was filled with students who’d grown up in Francophone or mixed ancestry households, but speaking the “wrong” form of the language—which one particularly insightful French teacher later explained to me sounded to her like 14th century peasants, and from which she recoiled with a deeply engrained class (and colonial “others”) disgust she was alarmed to discover in herself. Moving regions—to Canada and back again for graduate school after doing field work in Aotearoa New Zealand, and moving back to the States from Canada—provided progressively starker understanding of how far below the surface colonial relations could be hidden, or normalized, and how difficult it was for people to practice thinking or talking about the land relations, treaty histories, or racial hierarchies that have led us to the troubling social conditions we spend so much effort addressing in higher education and public activism (Case 2018)..

The variable literacy I encountered, at best, was accentuated by active inhibition addressing the legacy of colonial and neocolonial hierarchies and traumas, for example in a series of Uncomfortable Dinner Parties I hosted at the University of Minnesota. When invited, people would often ask, with unfeigned ignorance, what could be uncomfortable about discussing food, almost always flinching through the conflict with unbearable politeness when those of us on the invitation side suggested we needed to talk about how we justified whose land could be taken, whose labor compelled, and what kinds of working (and eating) conditions we thought were okay for some people but not others. In my first teaching job back in the States, I was reintroduced to the hierarchy of literacy built into state education about the literal history of colonialism, even in the history of the “winners” written into state textbooks. University students learning about debt crisis asked to step back further and further to understand the context when we watched the excellent film Life and Debt (http://www.lifeanddebt.org). Why don’t Jamaicans like the queen? they asked, or Why is the queen the queen of Jamaica? Recognizing how little these students studying society-environment dynamics with me have learned about colonialism, or the construction and maintenance of racial hierarchies, or segregation or gentrification—or really most of the dynamics of capitalism as they relate to environmental justice crises—helped me understand how their theories of change could be so extremely thin and fragile and not well rooted in the present realities that they’re being asked to face and fix.

This experience shifted my own scholarly work to include more active collaboration with teacher education programs, since it was students in training to be elementary school teachers in my classes who most actively resisted attempts to fill their significant educational gaps around colonial history and its contemporary implications. The privilege of living in different regions and tribal territories—and working within a range of educational and public contexts—has gifted me with the possibilities of relationships that have helped orient me to the contemporary presence of colonial conditions, rather than the dubious and deceptive comfort these students embraced, when challenged, of imagining colonial relations into the past. Witnessing students’ (and teachers’) resistance to the transformative learning act of wresting uncomfortable relations from a past too far gone to amend into a relational present with accountability demands that are immediate and pressing has motivated me to place practice with emotional labor (and tools!) front and center in my classroom and public teaching. These are designed for better understanding and navigating the felt experience of attempting to work on issues that are much more complex than someone signing up for an “environmental studies” class might expect—especially given the significant overrepresentation of environmental issues, however horror-filled, as a domain of privileged White people.

Many inhibitions to understanding the complex, “wicked” nature of socio-environmental problems are related to cognitive dissonance reduction: people whose life experiences have not made them witness significant disparities often don’t want to acknowledge or reify the warped power relations that have led us to creating and reinforcing the climate crisis, with all of its many components and impacts (DiAngelo 2018). From privileged perspectives where these impacts can be ignored, it can seem like not acknowledging the extractive and exploitative relations underlying most environmental problems helps keep those relationships from being real. Once I realized how much these self-protective habits were inhibiting exploration in my classes and public education and art events, I started equipping my teaching toolkits better with real-world examples that clearly showed the dynamics and relationships involved—and on centering Indigenous and Afro futurisms along with other powerful ways to look ahead without reproducing the status quo of White supremacy. This focus on working through examples with analysis as well as space for processing reactions helps in several ways. In addition to pushing back on the tendency to ignore or sweep difficult topics under the rug, it also helps undercut resistance to “critique” as equivalent to “complaining,” a critique of critique I encountered as more common in the hyper-polite Upper Midwest than in my Northeast upbringing. Further, teaching with texts like Raj Patel and Jason Moore’s History of the World in Seven Cheap Things (2017) and Chimamanda Adichie’s TED talk The Danger of a Single Story (2009) helps unpack how we have layered our own emotionally protective barriers on top of the harms of colonialism, assisting learners in understanding the importance of addressing social power dynamics together with the more technological-seeming problems of climate, for example, and also in recognizing how big a part our emotional recoiling from these problems plays in their reproduction. Such explanations of how we have gotten to the present crises also help, as Adichie notes, to reduce the tendency to fixate on the resulting problems we see without also seeing their history and structural and relational contexts. “Power is the ability not just to tell the story of another person, but to make it the definitive story of that person,” she explains. “The Palestinian poet Mourid Barghouti writes that if you want to dispossess a people, the simplest way to do it is to tell their story and to start with ‘secondly.’ Start the story with the arrows of the Native Americans, and not with the arrival of the British, and you have an entirely different story. Start the story with the failure of the African state, and not with the colonial creation of the African state, and you have an entirely different story” (2009). Foregrounding such analyses early in the class helps deconstruct built-in resistances to critical thinking, making more space for exploring social dynamics and also our reactions to them.

Such insights have encouraged me in my classroom and public teaching to more explicitly and methodically work through basic challenges, such as the challenge of talking about climate change, and also some basic strengths of our socio-ecological culture—our political and cultural ecology—particularly focusing on commons, for example, and on case studies of how people have successfully cared for environments collaboratively over time. I use prompts that help intentionally shift energy away from opportunities to remove oneself from involvement in complex global dynamics—or from the need to deliver “solutions” from a barely informed perspective—and that instead ask learners to consider what it takes to de-risk interventions, to support people to continue with difficult work, and to engage in repair and conciliation of social harms upon which our social processes rest. Following such introductions to topics, encouraging learners to come up with manuals that they would need or want to use to help support their own ways of addressing the issues at hand, that that would help other people join in it, has resulted in supportive manuals and toolkits slanted decisively toward really basic emotional care. These resources also model and explicitly show users how to demonstrate both affective skills and virtue shifts needed in the situations addressed, for example toward humility, adaptation to complexity, collaboration, community resourcefulness (Throop 2016).

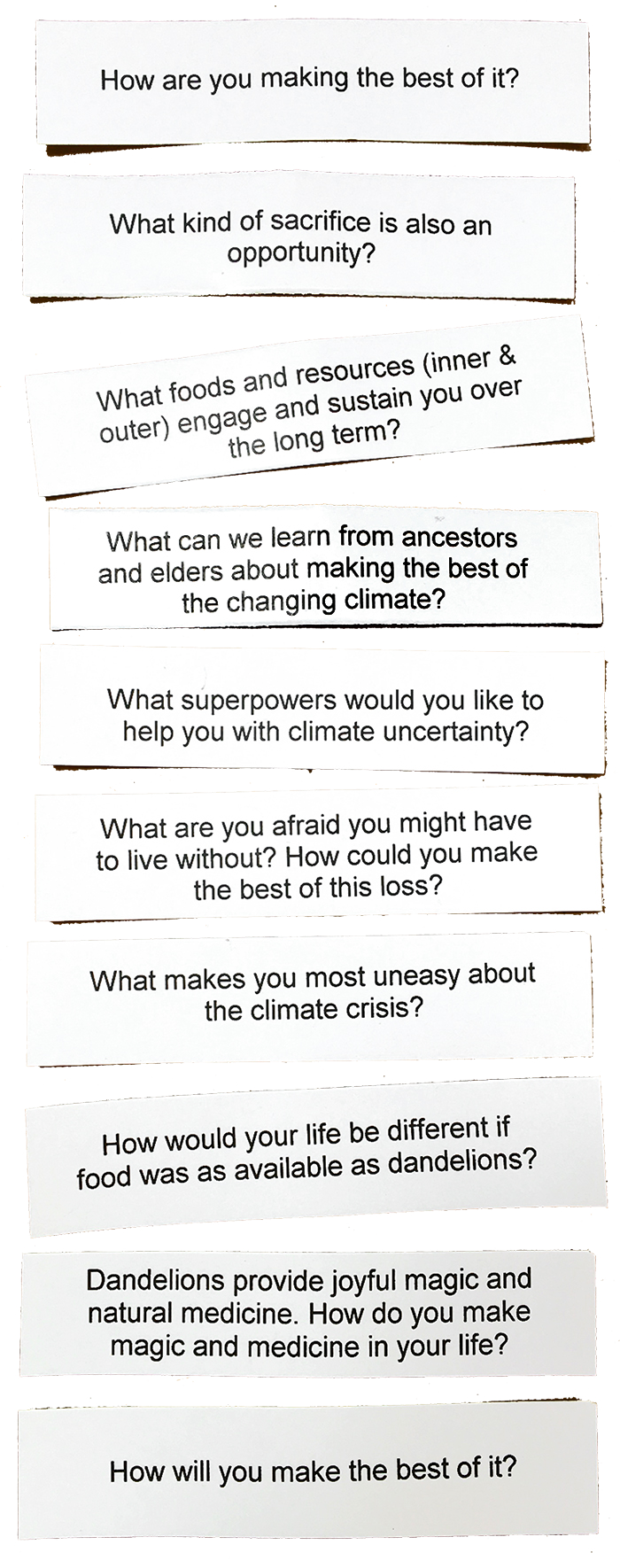

Prompts for talking about climate change from Making the Best of It Dandelion, courtesy Valentine Cadieux

Creating resources to help each other deal with the pressures of the care work demanded of them, and differentiating between different kinds of work—keeping, breaking, and mending, for example (Canty 2016), or scholarship, practice, or movement work in agroecological methods (Bowness et al., forthcoming)—and between different kinds of emotion, such as anger or despair (Lorde 1981; Keimowitz 2018), has given students practice empathizing with each other’s learning struggles. The iterative focus on a toolkit for supporting learning helped learners (both students in this class, as well as the volunteer guides in the Dandelion project) ask each other (and themselves, and me) what else they would need to learn to understand what we were covering in class, opening the door to more and more diverse foundational questions. Explicit attention to what supports might be needed to understand the topic at hand adequately also has encouraged meta-attention to why various histories or dynamics would not be well taught or understood, helping to mitigate feelings of shame or educational inadequacy and also helping to ease the weight of explaining racial injustices on students presenting marginalized identities.

Trauma-Informed Teaching: Acknowledging Why Things Hurt, Including Bewilderment, and Reaching for Affect

Rather than single out any of the students in my classes or public art project participants, I’ll briefly use myself at various points in my education to illustrate three kinds of learners I’ve been thinking about navigating between as I scaffold learning conversations in my classrooms and public events to try to orient them toward hope, while not injuring participants. (For one thing, I have not sought the consent of students for this kind of reflection; for another, I am learning the value of being willing to be vulnerable in this way in learning together.) This is not an attempt to create a comprehensive typology—there are many other kinds of learners, but these three vignettes and identities present particular challenges I’ve been trying to address in teaching for hope, and whose interactions I seek to ease: those who know our colonial conditions all too well from their own experiences; those who know they need to know, but are likely stuck in saviorism, or in fear of a wrong step in the fraught fields of identity politics; and those with conviction that they do not need to know more about others.

I’ll start with the last of these kinds of learners I’ve outlined. When I was an undergraduate student arriving at a private liberal arts college (and again when I arrived in a social science graduate program), I came with questions about the largely White and mixed Indigenous rural communities I’d been inhabiting, and I felt immediately barraged with an expectation of cosmopolitanism and the ability to take on much more global dilemmas than I felt prepared to. I was not resistant to learning about others, and was well familiar with class-war rhetoric, but my under-resourced schools had skipped the chapters on other countries (particularly on Asia and Africa), and did not cover domestic imperial expansions. I consequently experienced my struggles to use the language of the critical cultural turn (what is often now popularly dismissed as “postmodern neomarxism,” a field of cultural and structural criticism I now deeply appreciate, even if I gnash my teeth at the challenging storytelling styles I have inherited from this training)—or to understand the imperatives of dismantling intersectional racialized hierarchies—as my own lack of culture. This feeling that my culture was inadequate if I could not readily mesh it with others’, or with the centrality of anti-racism, was part of what made me feel uncomfortable, class-wise, in higher ed contexts and contributed to challenges in bringing what I learn and study back to my family and the social settings where I work. I can see this dynamic at play with students in my classes who have arrived from mostly White suburban or rural backgrounds and who find it challenging to not be aggressively defensive when experiencing the limits of what they know or have experienced. This defensiveness sometimes manifests very challengingly in the form of these students’ assertions that they do not need to concern themselves with those that “lost” the power struggles of history, for example, when asserting how long ago Indigenous dispossession took place (only ~150 years in this case), and how we can’t be held responsible for the past. Concerned about the characterization of colleges as havens for liberal discourse and as hostile to conservatism, students with such views tend to associate themselves with an individual virtual model of social morality and rule following while exhibiting significant gaps in education about the dynamics of flows of capital and labor across borders, or about the context or dynamics of other hot-button topics such as reparations proposals, international aid, or immigration. The Turning Point USA student groups I’ve witnessed have shown this dynamic, fueled by inflammatory and unreliable news sources, and as the elections increase news pressure, I see the same news dynamics directed aggressively at my parents’ generation as well. Notably, these news sources consistently use their insistence on a culture of respect and traditionalism to conflate the performance of respect and honor with a felt need for compliance, and even a maintenance of subjugation—one of the clearest demonstrations of the reinforcement of colonial mentalities in approaching contemporary politics, and a clear call for learning experiences that carefully and thoroughly explore how this colonial mindset has come to be, its effects, and its alternatives.

Along with students who are not so defensive but are still new to using the vocabulary of dismantling racialized hierarchies, these learners steeped in traditions of racial superiority are prone to micro (and macro) aggressions toward other students, fixating on accusatory “secondly” stories (as described by Barghouti in Adichie 2009) or, perhaps worse, adopting the language of marginalization in protesting “reverse racism” or the danger posed to them by rampant radicalism. These learners have also experienced dismissive disgust in intellectual contexts, which has reinforced protective defenses (for example of patriotism and loyalty, often in very propagandistic-seeming terms) and inoculated them against arguments for the value of progressive equity approaches. For these learners, being asked to critically analyze social disparities and differences that they likely have not yet encountered in any explicit way accelerates the learning process beyond a realistic pace. It also often reveals a fallacy of knowledge on the part of instructors, in which it is difficult to remember what it was like to not know something now that it is known (to them), and disgusted discomfort with the implications and consequences of such ignorance, as of gentrification, or dispossession, or neoliberalism, or the many causes of the symptoms of social dysfunction people can often see but not explain. These learners often need opportunities to learn about such newly encountered dynamics in ways that are neither too repetitive nor too painful for peers who live these realities.

Trauma-informed teaching may be important for successfully teaching resistant learners, and it can also help buffer other learners who, potentially, are negatively impacted by the collateral damage of resistant learners’ intellectual growth. I work not to burden the students in my first-year courses who are from disinvested Black neighborhoods, for example, not only during aggressions, but also when their well-meaning White peers struggle through discoveries of racialized discrimination, gentrification, and the history of colonialism, repeatedly naturalizing these, or when they stumble through newly acquired frameworks of intersectionality or race. In my own learning experience (like Professor Keimowitz’s in her previously cited account of facing increasing despair while teaching climate change), I have most inhabited this position while teaching systemic environmental racism to skeptical classes, finding myself reaching for the trauma of Bhopal or dibromochloropropane as a crutch—although I have realized it is all too easily experienced as a hammer—to keep myself armed with anger to be able to make it through a class without being myself disabled by despair.

Again, acknowledging the pain of learning—the bewilderment of new knowledge but also the witnessing of others’ ignorance—helps keep more available the practice of naming the often-difficult feelings involved in classroom and public growth. Setting up mutually developed and agreed-upon ground rules for discussion in the classroom can help build some of the basic preconditions for relative safety, collaboration, and the development of mutual trustworthiness—rather than centering the instructor as savior or protector. These can, instead, shift the instructor’s role to guide learning toward choosing, together, how to build community empowerment by facing the conditions that impede hope and choosing not to re-traumatize each other in the process. Creating supportive ways to address and work through trauma when it arises can also help. Beyond centering repair work, especially from the perspective of people and communities who may be underrepresented in the learning histories of those gathered, I share examples of reconciliation (or conciliation) processes, from the mundane—being ok with dandelions, rather than trying to eradicate them in fits of species purityism—to the more dramatic, as with the many academic examples available across Canada from its recent Truth and Reconciliation Commission process. I also work to normalize the experience of emotion as a valid part of the learning process. Desirée Williams-Rajee, in her brilliant 2017 acceptance speech of the University of Minnesota’s Institute on the Environment Solutions Prize for her work building equitable community engagement and climate policy making processes, cries through much of her speech—and it only makes it more arresting and beautiful, allaying the common fear that emotion will “get in the way.” Williams-Rajee makes it clear that it just takes courage, stability, and ease—skills that can be practiced.

I have already referred to Jeanine Canty’s brilliant essay “Seeing Clearly through Cracked Lenses” from her 2016 edited collection Ecological and Social Healing: Multicultural Women’s Voices in my reference to her typology of keepers, breakers, and menders. Here, again, I return to her work, which not only helps remove the potentially paralyzing pressure from late adolescents in the university setting as they attempt to come to terms with living up to the legacy of either breakers or keepers, calling them all into the more manageable and still pressing task of mending; this work also helps us name more explicitly that we are all starting from cracked lenses through which we see the world. This helps allay the pressure of perfectionism and the paralyzing pathology of needing to be right, conditions that are particularly salient to a generation that has grown up under the broadcast lens of social media and that greatly fears call-out culture. Recognizing the differential ways our everyday impacts on the world reproduce and reflect traumas helps learners come to terms with these conditions through a lens of repair, and hopefully, of hope. In the final section, I consider that middle identity of learners: eager for hope, yet cautious of stepping awry.

Hope for Transformative Interventions

The first decade (at least!) of my professional academic career would probably qualify as my sojourn in that middle identity I mention, where most students and public art participants I encounter reside. Having been clued in to the analytic lenses of postcolonial social science and feminist political ecology—so I was at least more informed and equipped with excellent toolkits—I was still often unsure how to navigate the conflicting pressures of academic performance as a community-engaged scholar and identity politics. In addition to academia’s tendency to disproportionately legitimize spectacular work and appropriate the stories of others, my academic generation lives inside the transitional phase where intents to stand behind the voices and action of marginalized people and address longstanding failures of representation, inclusion, and equity are often perverted into competitions to show whose community research can carry theory most elegantly. My rich history of rejections from federal grants tracks this, praising my community-led participatory research methodologies while also castigating me for not determining more clearly what outcomes our research interventions would yield, and often returning to directives to better fit savior roles: Why isn’t this research being conducted in the global south where it could have real impact? Why doesn’t this work seek to more directly tell communities how to eat, or to solve their food access problems with individualist innovation? The challenges of gaining more intercultural competence, and living up to the cosmopolitan and racial equity aspirations of progressive public life, are radically contingent on being rooted in a community, something that requires either existing community relationships or the competency and luck to nourish them. Learning how to nourish such relationships likely requires the mentorship of elders, in addition to the willingness to avail oneself of such guidance. The humility and competence to receive ancestor wisdom is crucial for real hope of rooting our learning relationships—and this rootedness in ancestors’ wisdom can be additionally challenged by the inherently countercultural nature of transformative learning.

The countercultural challenge of working on systems in need of transformation in a participatory way is, indeed, that if the work is “successful,” what they will become is unknown—this is usually a domain of hope that is in conflict with certainty. A central premise of community-based participatory research is that success will reflect goals the people in the systems have determined (Bowness et al., forthcoming). That often means that the people in the systems need to gain the literacy and systemic empowerment to be able to meet their goals and not just be compelled to do so exogenously. The uncertainty involved in this endeavor is joined by the need to balk culture: learning how to transform systems that are not working well for people means that you are inherently behaving in countercultural ways as well, and if you’re staying with the trouble, you’re engaging the sections of the systems that are perhaps most not working well, all conditions not necessarily conducive to rooting or growing health (or facile collaboration). By being countercultural, you are likely not eliciting the appreciation or fostering the relational goodwill of the powerbrokers in the system.

In doing this work, we are also rarely trained with the futurist toolkits of organizational “blackbelts” who go in and rethink corporations; in most higher education and public art contexts, the people who are working on systems change and sustainability interventions are people whose currency is already successful social intervention. They’re consequently carrying the weight of relationship maintenance, and relationship maintenance with community partners also usually involves more of this same kind of countercultural systems change—like brokering translation of pronouncements by departments of the state (of health and environment, for example), or universities and grantors, or helping to carry out projects and doing documentation and providing fiscal agency and grant writing, at the same time you’re getting students involved in those projects to deliver change. So, you’re also usually working two jobs, then you’re trying to do additional work in your own institution to get it to work better. All of this is outlining the likelihood of systems-change burnout. For these reasons, transformative learning carries a very high need for joy, solidarity, and functional process. The work and learning you’re doing need to be interesting and rewarding and the people you’re working with need to have each other’s backs and be good to work with, and if certain thresholds of relational accountability can’t be met, it’s very hard to stay healthy, rather than fall into jaded burnout and emotional dysregulation.

This has brought me to my new learning edge in teaching, along with many colleagues and students in that third group, the hope “keeners”(1): I find myself much more open to what the Association for Contemplative Mind in Higher Education (n.d.) sees as its mission, “the transformation of higher education through the recovery and development of the contemplative dimensions of teaching, learning and knowing.” After being struck at how often learners attested to their appreciation for unusually meaningful and even ceremonial experience—in my classes, public art events, and even in mundane sustainability efforts on campus—I started more intentionally engaging the field of scholarship well characterized in the collection Contemplative Approaches to Sustainability in Higher Education (Eaton, Hughes, and MacGregor 2016), and in Opaskwayak Cree scholar Shawn Wilson’s 2008 Research Is Ceremony. Willingness to move toward the spiritual and toward the cultural—not conflating those, but making space for both—as well as for embodied experience, has transformed my approach to environmental and climate justice education and public engagement. Turning toward teaching for affect—in attempting to get students to engage the emotional and lived experiences of colonization as the backdrop of the climate crisis, particularly—I have also significantly pared down my expectations for the habitual kind of evaluation research I saw as part and parcel of academics engaging in public work. Socially engaged critical social science and art are set up with the premise that you’ll do a thing and document a thing, and as a result of your intervention, there will be a change. Practically, you become habituated to doing work with interesting people on interesting problems in ways that have an impact, and where, if the project is successful, success is defined by systemic change, which is a high bar. The challenges built into this work are that you gravitate to systems that are in need of intervention, and that you often reside in domains unusually high in unknown unknowns, and increasingly, in spaces of crisis. In this long-term turmoil to which we commit ourselves wholeheartedly, if we are rooted in hope, evaluative strategies look much more like assessing whether intervention is plausible and what emotional resources we can muster to engage the necessary work for sustainability and change. We’ll probably need guidebooks for that.

Acknowledgements

Many mentors, colleagues, and friends have made the learning shared here possible. I particularly thank Melvin Giles for teaching and living peace and creating and supporting call-in culture (often by blowing bubbles when needed), and Jennifer Nicklay for advocating and nourishing care in all the learning circles. A Santa Fe Art Institute residency on Truth and Reconciliation provided space, time, and extraordinary colleagues that supported my reflecting on the shifts in my learning practice described above. My colleagues at Hamline have shared the practices with me, and Brian Lonsway and Kathleen Brandt have been wonderful co-experimenters in complex, relational learning. Finally, no one educating me in institutional contexts has lived community empowerment through learning how to nourish hope, with everyone they touch, more than Colleen Bell and Mary Rockcastle. This portrait of so much they have taught me about teaching is going to press on the occasion of their retirement, and I could not be more grateful.

Notes

(1)Although the more common definition of “keeners,” as someone who wails and sings for the dead, or to process grief, may also resonate with the challenges of hope in this dire season, I use “keeners” in the Canadian-dialect meaning, indicating students who are particularly eager and enthusiastic about the topic hope.

Works Cited

Adichie, Chimamanda Ngozi. 2009. “The Danger of a Single Story.” TEDGlobal, July 2009. https://www.ted.com/talks/

chimamanda_ngozi_adichie_the_danger_of_a_single_story

The Association for Contemplative Mind in Higher Education. n.d. “Home.” Accessed [insert date]. https://www.contemplativemind.org/programs/acmhe.

Bowness, Evan, Jennifer A. Nicklay, Alex Liebman, Kirsten Valentine Cadieux, Renata Blumberg. Forthcoming. “Navigating Urban Agroecological Research with the Social Sciences.” In Urban Agroecology: Interdisciplinary Research and Future Directions, edited by Monika Egerer and Hamutahl Cohen, 275–298. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Cadieux, Kirsten Valentine. 2013a. “A Field Guide to Making Food Good: An Interactive Tool for Participatory Research Supporting Difficult Conversations,” Public 1(1). https://public.imaginingamerica.org/blog/article/a-field-guide-to-making-food-good-an-interactive-tool-for-participatory-research-supporting-difficult-conversations/

Cadieux, Kirsten Valentine. 2013b. “The Mortality of Trees in Exurbia’s Pastoral Modernity: Challenging Conservation Practices to Move beyond Deferring Dialogue about the Meanings and Values of Environments.” In Landscape and the Ideology of Nature in Exurbia, edited by Kirsten Valentine Cadieux and Laura Taylor, 252–294 New York: Routledge.

Cadieux, Kirsten Valentine. 2016. “Other Women’s Gardens: Radical Homemaking and Public Performance of the Politics of Feeding.” In Doing Nutrition Differently: Critical Approaches to Diet and Dietary Intervention, edited by Allison Hayes-Conroy and Jessica Hayes-Conroy, 61–86 New York: Routledge.

Cadieux, Kirsten Valentine, Marina Zurkow, and Sarah Libertus. 2019. “Eating Climate Change with Making the Best of It Dandelion: Collaborative Public Art as a Mode of Future-Oriented Learning.” Transformations: The Journal of Inclusive Scholarship and Pedagogy, 29(2): 210–233.

Canty, Jeanine M. 2016. “Seeing Clearly through Cracked Lenses.” In Ecological and Social Healing: Multicultural Women’s Voices, edited by Jeanine M. Canty, 39–60. New York: Routledge.

Case, Martin. 2018. The Relentless Business of Treaties: How Indigenous Land Became US Property. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press.

Cuarón, Alfonso, dir. 2007. The Possibility of Hope. Short documentary on Special Edition DVD of Children of Men. London, UK: Universal Pictures UK.

DiAngelo, Robin. 2018. White Fragility: Why It's So Hard for White People to Talk about Racism. Boston: Beacon Press.

Eaton, Marie, Holly J. Hughes, and Jean MacGregor, eds., 2016. Contemplative Approaches to Sustainability in Higher Education: Theory and Practice. New York: Routledge.

Feed Your Brain. 2019. “Feed Your Brain: Working to Change the Culture of Food on Campus for Everyone.” Report prepared by the Community Collaborative (CoLLab) Research Team, Hamline University, Professor Susi Keefe and the Public Health Senior Seminar; Professor Valentine Cadieux and the Environmental Studies Junior and Senior Seminars: Problem Solving in Environmental Studies & Practicum for Studying Environments; Professor Curt Lund and the Graphic Design Seminar; and Professor Rachel Tofteland-Trampe and Topics in Professional Writing: Usability and User Advocacy.

Fry, Richard, and Anthony Cilluffo. 2019. “A Rising Share of Undergraduates Are from Poor Families, Especially at Less Selective Colleges.” Pew Research Center. May 22. https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2019/05/22/a-rising-share-of-undergraduates-are-from-poor-families-especially-at-less-selective-colleges/.

Jensen, Derrick. 2006. Endgame. Vol. 1. New York: Seven Stories Press.

Keimowitz, Alison Spodek. 2018. “I Felt Despair About Climate Change—Until a Brush with Death Changed My Mind.” Slate, March 9, 2018. https://slate.com/technology/2018/03/an-environmental-professor-on-learning-to-cope-with-climate-change.html.

Lorde, Audre. 1997. “The Uses of Anger.” Women's Studies Quarterly, 25(1/2): 278–285.

Patel, Raj, and Jason W. Moore. 2017. A History of the World in Seven Cheap Things: A Guide to Capitalism, Nature, and the Future of the Planet. Oakland: University of California Press.

Throop, William. 2016. “Flourishing in the Age of Climate Change: Finding the Heart of Sustainability.” Midwest Studies in Philosophy 40: 296–314.

Wilson, Shawn. 2008. Research Is Ceremony: Indigenous Research Methods. Winnipeg: Fernwood Publishing.

Kirsten Valentine Cadieux is the Director of Environmental Studies and Director of Sustainability at Hamline University. Professor Cadieux received her PhD and MA in Geography from the University of Toronto after completing an AB in Visual and Environmental Studies at Harvard and Radcliffe Colleges. Professor Cadieux studies collaborative knowledge practices related to food, agriculture, and land in the context of settler society cultures in Canada, the United States, and Aotearoa, New Zealand. She is currently working on the FoodShed, a collaborative online workshop and field guide to food movement efforts, and an accompanying podcast called “Eating Together,” foodfieldguides.com

For image credits, visit our issue image credit page.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.