Nick Sousanis Reflects on

The Fragile Framework

Abstract

A brief reflection on Richard Monastersky and Nick Sousanis's comic The Fragile Framework: Can nations unite to save Earth’s climate?, created for a special issue of Nature on the Paris Climate Talks.In late summer of 2015, an editor for Nature reached out to me to coauthor a piece with their science writer Richard Monastersky to coincide with the Paris Climate Talks that November. When we had the first conversation, I put forth some particulars about how I’d want to approach the piece. Primarily, rather than the sort of thing where I’d draw a lab-coated scientist or esteemed professor/journalist walking around explaining things in the comic, this would be, as is the case with my work in general, undertaken through the use of visual metaphor, the interplay of the words and pictures, and that I would use the affordances of the comics page itself to get the ideas across. This is a harder challenge—for me (what do I draw each page/panel?) and certainly for Rich—he couldn’t simply give me a script of things to draw and I’d fill it in with pictures. But they went for it anyway, and so began a rather epic collaboration of back-and-forths by phone and email where we worked to hammer out how to get all these ideas across in an extremely small space, without oversimplifying anything and making sure it was all clear.

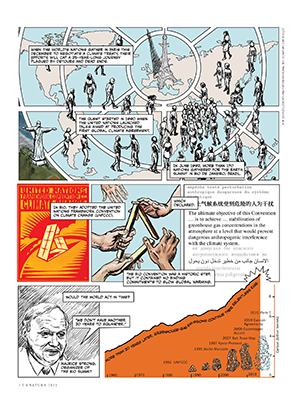

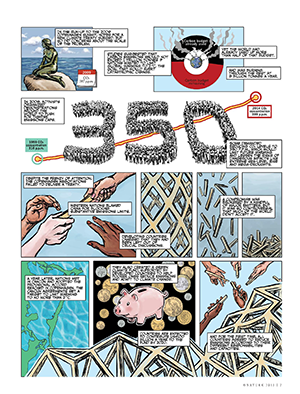

One of the things that stands out to me from our initial brainstorming is how to get across the seriousness of this issue without making it feel hopeless, but also without being overly optimistic. It’s a fine balance to achieve. Because of my not doing this as an illustration piece of existing text, it meant I was reading everything I could (that Richard sent me) to get up to speed on the ins and outs of climate science, the history of climate meetings, and such. Between our conversations and being immersed in the material, what struck me was how massive this problem was, and the only thing I saw as remotely similar (and it is a drop in the ocean in comparison) was the Apollo project and all the hands that went into getting humans onto the moon. This triggered an association—the talks were in Paris, it made sense that at some point there’d be a nod to the Eiffel tower and I thought about that structure as quite resembling the scaffolding look of the gantry that people used to access the Saturn rockets. Hmm, this had some potential. One of the hard things about the piece was how to hold all this different information together in a coherent package without that little explainer character running around. But this scaffolding, or framework, might just do the trick. So I pretty quickly sketched out this idea where on each page you’d see a little bit of scaffolding being built, sometimes falling apart, but on each page we’d come back to it in some way as a kind of narrative thread, and then in the final page it would take main stage and we’d see a kind of “handoff” from adult hands working on it to children’s hands that would make up the bottom. In this way, I hoped to get across the idea that this is an ongoing thing and while we’ve made some progress, there’s a long way to go, and it would be our children and their children that would have to keep building. A balance presenting what we’d built thus far and the challenges ahead.

I sketched this out and snapped a scan and sent it over. No one could tell what I was up to from the quite rough sketches I’d sent. But we proceeded with that anyhow. And then in doing my reading, I learned that the first climate conference was titled the “Framework Convention on Climate Change” and the poster featured this somewhat scaffolding-like triangle erected on the globe. I’d had no idea, but this meant that I could tie it all together (and in fact I reproduced that poster on the first page in order to draw a direct connection from the very first gathering to now). I had my literal “framework” metaphor, and from there I could start to bring all the different pieces together.

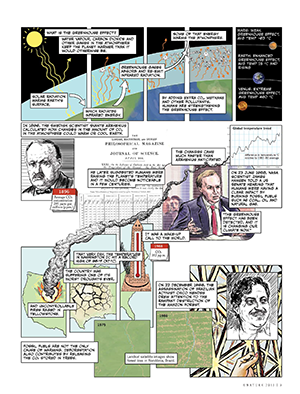

While the flat and static nature of comics is at times disparaged in comparison to flashier, moving pictures on screens, this static quality actually is a great strength. It means we can read at our own pace, lingering here, accelerating there, and perhaps more so, the author can organize multiple juxtapositions across each page (and as with the framework, throughout the whole narrative) that can speak to each other in nonlinear ways and produce generative conversations between them. My approach in making comics is to be equally attentive to the needs of the material and the aesthetics. So, yes, you could make something with lots of good research in it, but if it’s not visually interesting, it doesn’t work, and conversely, if you draw a lovely picture, but it’s not saying much—time to rethink the composition. This means lots of sketching, digging deep into the material for visual information, and really doing a lot of looking at your sketches to see what kinds of connections are generated from the pieces you are assembling. The looseness of my sketches, which made it hard for folks at Nature to read, is key to my process because it allows me to reinterpret them and make new connections in my own drawings.

Right before publication, there was a discussion with editors at Nature as to whether to call it a comic or a graphic novel. I argued strongly for comic—I mean it was only eight pages and graphic novel, especially in this case, was rather pretentious. But others felt there would be those who would belittle it if labeled a comic. Ultimately, they did go with comic, which prompted a colleague to ask, after publication, Who came after you first—climate change deniers or comics deniers? It was about 50/50.