Abstract

This essay describes the experience of being present at performances in correctional facilities (PCF), with a focus on the PACE program at San Francisco County Jail #5 in San Bruno, CA. PCF are full of possibility and fraught with pitfalls. The experience of attending one of these events can interrupt assumptions about the incarcerated and create powerful feelings of connection; it also risks reinscribing roles created by a penal system built on white supremacy. Our narrative balances one author’s experience as a spectator against commentary provided by two PACE facilitators and one alumni, as well as a second inside performer who has participated in multiple PCF programs. All five authors reflect on the experience of watching, being watched, and what needs to come after. Thinking about our involvement with PCF inevitably leads us to reflect on broader themes including race, mass incarceration, and social justice leadership.

The Performing Arts and Community Exchange (PACE) takes place at San Francisco County Jail #5 in San Bruno, CA. Now in its eleventh year, PACE is a semester-long collaboration between “inside” and “outside” students under the facilitation of doctoral candidate Reggie Daniels and Associate Professor Amie Dowling. Outside students are fulfilling a requirement for the Performing Arts and Social Justice major; inside students may receive GED or college credit for participating, provided they are enrolled in the jail’s educational program. At the end of the semester, one final performance is open to a small invited audience of outsiders as well as inside audience members.

The video highlights from the PACE performance cannot be shared as the performers did not have the opportunity to consent to its public distribution. Their contributions go unrecognized, nominally for their own protection. This is one way in which, in an effort to prevent exploitation, human subject protocols and ethical concerns do not always align. This is the audio from the final edited video.

Poet/speaker: Corwyn DuVernay. Image: Lawrence Rickford.

Act One: Preshow

Oona:

The narrative that follows describes my visits to San Francisco County Jail #5; I also draw indirectly on my experience as a PCF spectator at San Quentin and Solano State Prisons. It is a narrative about learning, about the continual reminder that my own privilege structures my response to these physical spaces and the individuals who people them. My account is annotated by the perspectives and experiences of people who have created these performances. These coauthors share challenges, doubts, and caveats they see in this work, but this is also a narrative about the spaces for success—for connection and for what Reggie will call “shifts.”

1

San Francisco County Jail #5 is up a winding, tree-lined road in the hills of San Bruno, just south of the city. I sign in at the security desk and show my ID to the uniformed guard. I check my pockets to ensure that I have not accidentally brought in any other personal belongings. I stand in the lobby with other audience members, many of whom greet each other with smiles or hugs and talk in low voices as we wait to enter the jail.

I am a white, female, middle-aged professor with a PhD and a background as a theater artist. Amie has invited me to the performance because I expressed a keen interest in the PACE class. I have never been to a correctional facility and have had almost no interaction with law enforcement. At the time, entering the jail’s spacious lobby, with its rows of vinyl chairs and enormous plate glass windows, with its ID checks and metal detector, did not seem unlike going to the airport.

Reggie:

It's very difficult to go from a social justice, religious school to an institution where there's a very paramilitary environment. You're learning all of these things about equality, and then you go in, and you're being talked to by a captain or the lieutenant, and they're saying, “These human beings are very manipulative. You can't trust them. You gotta watch them. They'll play you any chance they get. Don't give them any information. Just be on guard.”

Amie:

How “watching” happens in jails and prisons, and what intention is behind it, is wide ranging. On a very basic level, surveillance is constant. The jail’s deputies watch through cameras, noting actions and behaviors. There’s the outside students and the inside students, separate groups coming together from two different institutions. Their projections, based on assumptions they have about each other, initially shape how they see one another. There are the other men in the pod, not in PACE class, who are looking through cells at us as we rehearse. And at the end of the semester, 15 weeks later, there’s the watching of the final performance by an audience: people who work in the jail and outside guests from USF and the Bay Area.

Reggie:

There does not tend to be a lot of concern on the inside learners’ behalf because oftentimes they are viewed as just perpetrators. There's a very singular one-way of viewing it, and so it's usually that the protection is always on the side of the outside learners. But what I say to the guys on the inside . . . I just talk to them about staying focused on what their goal is, just getting out and getting back to their families, getting themselves back into a work or school situation, and really thinking about how this experience in PACE can help them in that way.

Troy:

I was at the beginning of earning myself a leadership role within the jail. As one of the co-facilitators/senior advocates, I stepped up to many challenges. A difficult challenge for me was speaking to large groups, something I knew I had to overcome in order to become successful at facilitating, as well as life generally. When I was initially approached about participating in the upcoming PACE class, I hesitated for a moment, had some doubt, and did some reflecting. I asked myself, “Why am I here? To work on my shortcomings in every aspect.” What better way to work on and/or tackle my fear, I thought. Before I allowed the tug-of-war within me to get the best of me, I decided to just dive in and give it a shot. I didn’t realize at that moment how valuable it would become to my growth. I would go on to participate in the PACE program for the next three years, for a total of four years in all.

Reggie:

You can see the division between the inside students and the outside students when they first come in. It's like a wall. The outside learners, USF, they come in, and they all kind of group together, and then the guys kind of group together. And as they start to do the theater exercises, as they start to talk and open up throughout the semester, we see this wall begin to disappear and you just see a classroom of learners.

Oona:

After being buzzed through a large security door, we are led down long hallways painted mint green, with white linoleum floors. The walls are almost completely bare, except for the occasional safety poster (“No live firearms permitted beyond this point”). We do not see anyone else as we travel up in an elevator and down another hall to Pod 7B. We enter the pod, and my first thought is that it feels surprisingly normal. The carpet is grey, the lighting is fluorescent, and the table and chairs are heavy metal, bolted into the floor. There is the faint smell of an old building. This central area could be a conference room at a community college or hospital; it could be a space in any midrange public institution where functionality and longevity are the primary values determining the architecture and décor.

Troy:

My initial perceptions of the audience as they arrive are: curious, cautious, intrigued, some anxiety, and some excitement. The preparation as well as the performances give me a sense of freedom and connection with the audience, those of whom may otherwise arrive defensive and/or have a negative view of the PACE performers.

Oona:

I take in the rest of the room and any familiarity I feel towards this space ends. To my left is a raised structure: an observation deck. The deck is elevated several feet and the front is a large semicircular counter that protrudes into the center of the room. A uniformed member of the prison staff is seated on the deck above, his body almost entirely obscured. He greets us mechanically, dividing his attention between surveying the room and watching a security screen in front of him. I follow the deputy’s gaze to the right side of the room, where an enormous wall of plexiglass rises two stories into the air. I realize that these are the pod’s cells: 12 on each level for a total of 24 cells, the “homes” of 48 incarcerated men.

2

Amie:

The walls between inside and out are built not only to keep people on the inside in and disappeared, but also to keep those of us on the outside out. Because of this separation, images from popular media are able to create a narrative about who is incarcerated and why, perpetuating a voyeuristic relationship with people inside jails and prisons.

3 In the PACE class, inside and outside students examine and question that narrative together. Our work throughout the semester frames mass incarceration as more than individual acts of criminality or individual responsibility. Rather, the United States’ punishment system is a much larger problem, at the root of which is institutional and racial inequity.

4 Inside and outside students discuss readings by Michelle Alexander, Tara Yosso, Emile DeWeaver, and others. PACE performances draw on personal experiences

and analyze mass incarceration as what Alexander describes as “. . . a comprehensive and well-disguised system of social control that functions in a manner strikingly similar to Jim Crow” (2010, 4). PACE strives to develop a creative process that supports humans in an inhumane system, while asking questions about the uses of locking people away in the first place.

Oona:

I avert my eyes, willing myself not to stare at the men in the cells. I am unable to see how large their cells are, what amenities they have, or how the doors function. I do not look at what men have placed on their walls and tables. I glance only briefly at the men themselves, who are now looking out at me and the other visitors. Some are waving, some place their palms against the glass, some continue what they were doing before we arrived. I am intensely aware of being white and female. I do not feel frightened; I feel deeply uncomfortable. I turn my attention toward the far end of the room, where a small gymnasium with a basketball half court is filled with folding chairs.

5

Act Two: The Performance in Snapshots

You are guided down a hallway to an elevator that will take you to Pod #5. Inside the elevator, three women’s voices—outside students—harmonize in haunting and celestial tones. “Can you see me?” they sing.

Oona:

Like most devised theater, a PACE performance is multifaceted and may include monologues, movement sequences, live music, dramatic scenes, rap, poetry, and audience participation. Rather than relying on a linear narrative or fictional characters, the performances highlight personal experiences that coalesce around specific themes. For the most part, performers do not take on fictional characters, but present as themselves or as members of the ensemble.

6 Outside students perform alongside inside students, but it is the inside students who take center stage. The inside performers appear to be almost exclusively men of color and overwhelmingly African American.

7 Many appear to be around the age of my students at San José State, but there are also several older men.

Amie:

In 2017’s

Nothing About Us Without Us, the inside students framed their creative choices by highlighting the ways they have developed navigational, aspirational, familial, social, and resistant capital.

8

At the front of a classroom, a performer raps a lecture. He references a complex diagram drawn on a whiteboard to explain a curriculum he has designed about breaking the cycle of gang violence. From the periphery of the room, inside and outside performers interject with personal stories about their experience with violence.

Luke:

The people on the outside bring in what I call the “institution of taught,” meaning they come inside thinking they’re going to see threatening images of what they’ve been taught to see. Images they’ve seen on various cop shows on CBS, NBC, CW, and FOX News. Performing for them is different because they leave having changed their minds about the community of the incarcerated. Performing for inmates carries with it a different energy because “we are oppressed” and in that oppression is clarity of connection. Inmates don’t need that much set up; prison trains you to observe, orient, decide, and act. Prisoners just get it!

Troy:

It’s a lot easier for me to perform and/or address a group of individuals that I’m familiar with as opposed to those I’m not so familiar with. Aside from being familiar with my peers, we have many similarities/experiences. Having understanding and being able to relate to each other eases communication for me, as well as how I may think I’m perceived.

A performer enters and greets the audience regally. He is wearing an elaborate Egyptian headdress made of paper.

Amie:

The gaze goes both ways during the performance. As the audience watches the performers, the performers watch the audience. The artists/performers are the authorities of their life experiences. This flipped gaze provides agency to individuals who are watched by officers/cameras for compliance and behavior 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, sometimes for decades.

Reggie:

Behind the scenes, not just the inside learners but the outside students are sometimes going through things. Definitely the inside guys are struggling with broken families, court, not knowing how their case is going to resolve; they have all these issues. I think it’s important that we recognize the choice of putting all that aside, of being grounded and being present in that room, not only for the performance but for the 15 weeks it took to create work that conveys a message that they think is valuable.

A young black man reads a declaration as the ensemble hums softly behind him. He reminds the audience that due to his race, he has been taught that he and his family are nothing, and that he feels helpless to change that attitude. “Are we not of value?” he asks. “That’s the message I’ve been made to receive and forced to believe. But will I? No. Hell, no. Will you?”

Luke:

I see the power dynamic during a performance as a relationship between equals, and I believe that for any relationship to flourish, the needs of both partners must be met. The audience holds the power because they don’t have to give up their day and come to a prison to experience theater. They could go to the American Conservatory Theater, Berkeley Rep, or Marin Shakespeare. Yet they choose to come and willingly become vulnerable by opening up their feelings to us for a short time. The performers’ power is born from our incarceration. We willingly give up our perception of power, and drop our prison masks. We give up the men we’ve had to become in order to survive the harsh reality of being in prison [in order] to share the one thing we have in common with our audience and that is our humanity.

9

Troy:

Throughout the performance I notice many in the audience lean forward in their chairs, intensely focused, no one appearing to blink an eye, some tears of sadness and joy throughout some of the performances, followed by calmness, applause, chatter, smiles, and laughter, a clear indication of a successful performance, connection, affecting lives in a positive way.

10

Oona:

I begin crying during the first scene of the performance. At one moment I am crying so hard I worry that I will distract other audience members.

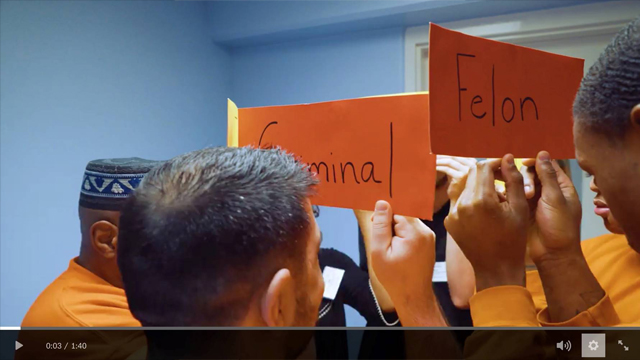

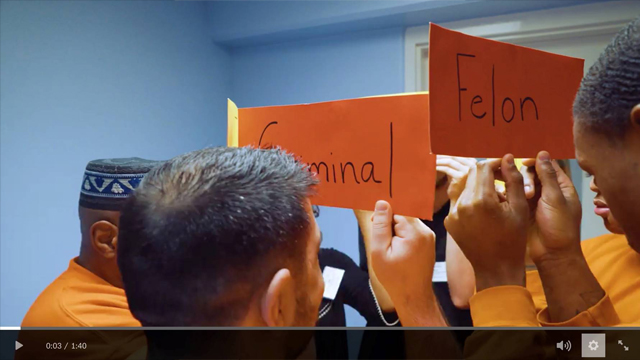

Six performers stand together on a stairway. They step up or down in response to questions about themselves and the resources available to them, including education, support networks, and their lived experience. As the questions continue, the outside performers move progressively closer to the audience, while the inside performers climb higher and higher. At the top of the stairs they hold up handwritten signs. Behind the audience, a performer shouts the text. “Are you desensitized?” he calls out. “Are you scared? Are you comfortable?”

Luke:

I don’t [watch the audience during a performance with Artistic Ensemble], not on a conscious level. It would interfere with the truth of the piece. Yet I do see people. I’ve seen laughter, I’ve witnessed people shed tears of joy and pain, and I’ve watched people touched by what they’re watching. Am I invested in what the audience thinks? Only to a minute degree. It’s important that I’m recognized as an artist/singer/dancer/poet/performer. I’ve worked extremely hard to be able to perform at the level that I can and I’m still learning and, more importantly, I’m not done! Artists are the voices of the people in every age. We are the hurricane in the calm of every institution that chooses to oppress its citizens. However, it’s even more important for me to be recognized as a kind and good man as my mother raised me to be.

A “family portrait” is being assembled with the confusion typical to this activity. Some relatives look into the camera, toothy smiles plastered on their faces, even as they continue to jockey for position. As the elbows and insults fly, the squabbling escalates to a full-blown argument, until one family member calls for peace.

Amie:

What experiences and political perspectives outside audience members have are wide ranging; some have been incarcerated, some are activists, while others have never questioned or given much thought to incarceration. For those audience members, the live performance may be the first time their assumptions about people who are incarcerated get interrupted. There can be a dissonance between what they walked in believing about prisons and the people housed in them, and what they hear, see, and feel during the performance and in the postshow discussion. I’ve seen this manifest in multiple ways, including a utopian naiveté.

Reggie:

In society, we're conditioned. “You're this. You're in this group. I'm in that group.” Then at the show we see all of these different people from different walks of life—families, law enforcement, community members—and the inside guys feel the intimacy with the audience and are held in a very gentle way; it validates them. When these guys feel like they're being received and heard, that’s when I've seen folks—not everybody—but I've seen folks get a shift.

An inside performer sings a song about his grandmother. His voice is soft and gentle as he repeats the chorus, “I wish that I had one more day, one more minute, one more hour, with you.” The ensemble joins in.

Reggie:

There is a tendency to think of folks inside in this very one-dimensional, perpetrator kind of way, and then you see this project that challenges the structures of power. Our last performance was very much about racism, discrimination, deficit thinking. Sometimes it's tender. Sometimes it's bold and endearing. Or sometimes, somebody's being really vulnerable about losing his mom or going through addiction and feeling the loss of self and feeling totally powerless. There's this range of things that happens in this performance, and it's real.

Troy:

More so than to be recognized as a performer, I hope my message is heard/felt and creates change and understanding in others’ hearts. When on stage, my hope is to project a genuine image that’s totally opposite of the stigma—judgment and labels—that’s placed on the incarcerated. When an audience sees me on stage and listens to my message and/or experiences, I hope that they are watching their neighbor, a good friend, coworker, a family member who has traveled down the wrong path, yet hasn’t given up on the search for change, the course of redemption/positivity.

Three performers are at a bank of pay phones, calling friends and relatives on the outside. A recording announces that their time is up. One at a time, they say goodbye.

“I love you.”

“I love you.”

“I love you.”

Act Three: Postshow

Oona:

Inside and outside audience members file out of the tiny gym into the central area, where a large, jovial crowd is forming. Two sheet cakes are being sliced and passed around. I watch the performers greet each other ebulliently. Like typical actors, they congratulate each other and review memorable moments of the show. I see other outside audience members approach performers and introduce themselves, sharing their responses. Some outside students are tearing up at the realization that this is almost the last time they will see each other (there will be one more meeting to debrief the performance and say goodbye). I begin a conversation with a man who was not part of the performance. He is an artist; he goes to his cell and returns with some sketches, including one he is working on for his daughter’s birthday.

Reggie:

The cake party is a big celebration. Who doesn't like sugar? But really, it's about the culture around food where people have an opportunity to have a very social experience that's close to a family barbecue or a summer get-together. I hear the guys say that they like being seen in this light and appreciated for an intellectual, emotional contribution that they made. Then they get to have people ask them questions about it and be curious about it, and they get to start to explore a new identity and a new role that is not connected to a street name or street image.

Luke:

[I know an Artistic Ensemble performance has been successful] when an outside member comes up to me and tells me that what I did made them look at something in a different way. My piece caused them to think of a family member, a social issue, or their desire to know where I came up with the idea they just saw. Successful also means when I am completely drenched in sweat and exhausted afterwards—I’m talking about when I would go back to the cell and sleep for hours. Successful means that the pieces I’ve created and performed have inflamed thought; in a way, it has led audience members to a safe place. Where uncomfortable, and comfortable, discourse afterwards, between audience members and the cast, is necessary.

Troy:

Each year on the day of the performance, I thought how nice it would be if family and friends were able to attend. A DVD of the performance was sent to my sister. She told me she posted the performance to other relatives that we have in different states, relatives I haven’t spoken with in many years. The response was that everyone was pleasantly surprised and spoke highly of me. I felt appreciated, despite my situation.

Amie:

In the state of California, if you are related to someone in jail or prison it is next to impossible to volunteer inside or to attend an event, such as a performance.

Luke:

I wish Governor Jerry Brown, Angela Davis, and women who are incarcerated could see our work. [And] the commissioners who sit on the parole boards, because our pieces aren’t solely for entertainment purposes.

Reggie:

Research says what lowers recidivism is connectivity. The more connected folks are to people, individuals, and organizations, the higher the percentage of people coming out and staying out. I think that there's a way that that also happens by something as simple as a judge or parole officer coming to the performance and viewing someone who may be on their caseload, that they're in charge of sentencing, coming to see them in a different light.

Act Four: Post Mortem

Oona:

The cake plates are thrown away. Plastic forks are collected and counted. Guards begin to direct the inside men back to their cells. The crowd slowly separates to either side of the room. As the inside performers and audience head into their cells, the outside audience spontaneously bursts into another round of applause. I clap and wave, tears welling up in my eyes again. A few performers wave back. I do not want to stop looking at them.

Troy:

I enjoyed the ambience up until the moment reality hit following the departure. It was a harsh reminder of my predicament, all that I was missing on the outside, my status/value as a human, and the stress and despair that comes with wondering how much longer I will be incarcerated. One moment I’m this prestigious Shaman, someone special/appreciated; within seconds I’m a disgrace to society, an outcast. At the end of the day I’m considered just a number, a second-class citizen; my dreams and life as I know them in this vast world are limited to that of a very short leash.

11

Amie:

It’s important that art trouble the narratives of good/bad, victim/perpetrator; these are false dichotomies that create and perpetuate opposition. The performances are not intended to entertain, numb, or relieve audiences. They are not intended to create a sense of utopia, but to raise questions and doubts about our country’s system of punishment.

12

Reggie:

Oftentimes when someone comes in and sees a performance, there's an emotional connection . . . it feels very humanizing. These emotional connections are not happening in enough spaces. People can project onto the performance different feelings. It’s a process of opening up, an initial reaction to something that is not familiar. If there is time given to reflect on those emotions, it can be a teaching and learning moment to create more conversation. That conversation should inform better actions and better practices. Having these discussions about where our emotions come from and how we’re responding to feeling connected—and bringing these conversations into white and privileged spaces where they're not happening—I think that this work could be a catalyst to that.

Oona:

The audience members walk back down the hallway. Audience members murmur to each other about the power of the performance. We ride down in the elevator. We wait at the security door to be buzzed through. I collect my ID and sign out. I walk out to the parking lot. I get in my car, and drive past the entrance gate, where a guard checks my ID for a final time, glances in my trunk, and waves me on.

13

Luke:

Artistic Ensemble pieces speak on justice and injustice, we challenge the social status quo of much that is just accepted but shouldn’t be. Our performances are “calls to action” for the people to wake up and pay attention to what the 13th Amendment has done and what it’s doing. That prisons are about companies making millions of dollars off the backs of human capital. That the system they think is about justice is not about justice but how much time can we give a man or a woman; that their political votes are key to ending mass incarceration in California.

Troy:

I haven’t met anyone who doesn’t want to feel loved, accepted, and appreciated. [H]onoring others’ experiences [can] lead to better understanding—a giant step forward in changing how others are viewed and treated, especially the minorities who fill most jails and prisons.

Oona:

I cannot speak for the experience of other spectators, but it is impossible for me to witness this work and not acknowledge the unnatural evil that is mass incarceration, as well as its connection to white supremacy. The result is that while I continue to attend these performances, while I feel compelled to attend them, I am increasingly uncomfortable in these spaces. Does my attendance endorse the existence of the institution? Does this outweigh my commitment to seeing and hearing what these performers have to say? Does my presence really benefit the performers?

14

Amie:

I’ve been working inside jails and prisons for over a decade, and part of the reason I’m permitted to enter these spaces is, as a white woman, I’m not suspect. My white skin privilege gives me access to facilities that is often denied to others. I believe that I need rehabilitation, that people on the outside, white people, need rehabilitation to recognize what Robin DiAngelo describes as “the unaware, unspoken, unmarked, privileged aspects of white racial identity that lead to racist policies and practices” (2012, 133). How do we interrupt the projections and assumptions that perpetuate dehumanization? And as we undertake this work to become more human, and begin to understand the harm done by white supremacy, how do we hold our own and each other’s complicity?

Reggie:

I think about how the jails benefit from these performances happening inside and how they get to profess that they're doing social justice work. And that maybe happens on a very surface level, and I think that all too often spectators, people who come in and view the performance, get this utopian image that this so advanced, and this is beautiful, and this jail is lovely. That's not really the truth. I still see a pattern of people of color who come from marginalized communities doing the one-on-one service providing. But when it comes to the resources and the development of curriculum and the decisions about how the resources are dispersed or the direction that curriculum or organization will go in, there are not people of color in positions to make those decisions. Until this work becomes more equitable, it has the face of social justice, it looks really nice, but we have a lot of work to do.

Notes

1 Just as my coauthors’ commentary may deepen or challenge my observations, I have in turn added some endnotes to provide context from related literature on their commentary. We have chosen to place this content at the end of the essay in order to privilege what Diana Taylor calls the “repertoire,” i.e., embodied, lived experience, over the “archive,” i.e., official records, statistics, and scholarship (Taylor 2003).

2 San Francisco County Jail #5 was designed as a panopticon. Although the jail was opened in 2006, it is based on the eighteenth-century ideas of social reformer Jeremy Bentham, who argued that the knowledge that they were under constant surveillance would cause prisoners to regulate their own behavior (Cate 2008). For more on the panopticon and prison, see Foucault 1977, Adams 2001.

3 In his taxonomy of how people experience correctional facilities, Jeffrey Ian Ross uses the term “prison voyeurism” to describe an engagement that “fails to contextualize the myths, misrepresentations, and stereotypes of prison life” (2015, 397). Although some have argued that popular shows such as Orange Is the New Black can covertly advocate for prison reform (Schwan 2016), representations of prison life in popular culture also contribute to what Michelle Brown has called “penal spectatorship,” our participation—albeit from a distance—in the criminal justice system (2009, 8). As Brown describes, the penal spectator is “secure in his or her place within sovereignty and the opportunity to exercise exclusionary judgment from afar” (8).

4 There is a considerable body of work on the inherent racism of the criminal justice system, including disparity in the racial composition of prison populations (Nellis 2016), incarceration as a method of race-based social control (Davis 2003; Khan-Cullors and bandele 2018; Nixon et al. 2008), or as an extension of slavery and post-slavery racist public policies (Alexander 2010; Chammah 2015). Alternatively, Danielle Dirks, Caroline Heldman, and Emma Zack (2015) have written about “white protectionism” as a way in which whites are able to avoid designation as criminals (160). Racial inequity is fundamental to how and why our justice system has developed in the directions that it has, as well as to the authors’ experience of it. To speak anecdotally, I (Oona) have attended eight performances at three institutions. Based on my visual assessment, the performers have been almost exclusively people of color; the vast majority were African American. In terms of content, race, and specifically blackness, have been a fundamental theme in all of the original performances as well as some of the scripted plays I have attended. For these reasons, it has been impossible for me to consider PCF without considering how race plays a role in its conception, execution, and reception.

5 For me, the discomfort of being inside a prison was in large part due to my awareness of my privilege as a white person. On this phenomenon, Teya Sepinuck writes of spectators, many of whom were coming to a prison for the first time, “seeing prisoners . . . looking at them through the windows became, for many, a confrontation with the reality of racism and imprisonment that left them frightened, outraged, and overwhelmed” (2011, 176).

6 In an article on performing Shakespeare with women in correctional facilities, Agnes Wilcox writes, “Each inmate is able, within the play, to slough off her identity and previous images of herself, which are often images of failure and victimhood” (2011, 250). While Wilcox appreciates the distance that she argues Shakespeare affords, the aesthetic framework of devised performance, as practiced by PACE, requires performers to think and speak as themselves. In this way, it is not about escape, nor is it about using another character to reflect on oneself. Rather, PACE uses performance for self-reflection, but also to critique the systems that perpetuate disparities in wealth, opportunity, and access to resources.

7 A 2016 report from The Sentencing Project found that, nationwide, African Americans are incarcerated at a rate of more than five times that of whites (Nellis 2016). According to the Public Policy Institute of California, at the end of 2016, although only 6% of the state’s male residents were African American, 29% of the male prisoners in state prisons were black. In California, the incarceration rate for African American men is 4,180 per 100,000. Latinos are incarcerated at a rate of 1,028 per 100,000. White men are imprisoned at a rate of 420 per 100,000, while men of other races are imprisoned at a rate of 335 per 100,000 (Goss and Hayes 2018).

8 See Tara Yosso’s Whose Culture Has Capital? (2005), in which she uses critical race theory to challenge hegemonic conceptions of cultural capital by illustrating the value of “community cultural wealth.” This theoretical shift reorients towards “the array of cultural knowledge, skills, abilities and contacts possessed by socially marginalized groups that often go unrecognized and unacknowledged” (69).

9 For more information on the Artistic Ensemble, see http://www.aesq.info/.

10 Troy’s experience corroborates research on prison spectatorship. In his dissertation on attitudes towards the incarcerated after interaction with a prison choir, Edward Messerschmidt found that audience members attending a prison choir performance for the first time demonstrated “significant, positive change” in how they regarded incarcerated people, as measured through both quantitative and qualitative means (the Attitude Towards Prisoners Scale [ATPS] and answers to open-ended questions) (2017, 131). Some of the themes included surprise at the articulateness of individuals who introduced choir selections, being moved by the pain, humor, and passion of the performers, and recognizing similarities between themselves and the choir members. Messerschmidt concludes that “many participants’ attitudes changed from a leery, ‘us vs. them’ mentality to a viewpoint that celebrated their shared humanity with incarcerated people" (163). Other writing on the positive impact of performance on attitudes toward the incarcerated includes work on dance (Dworin 2011), performance with juveniles (Taylor 2011), and Shakespeare (Wilcox 2011).

11 Julia Taylor writes of observing this metamorphosis from celebrated performer to prisoner after a performance at a juvenile detention center: “An energetic audience surrounded us as we exchanged smiles and last hugs. . . . by the time I realized it was over, the girls were already in their transport lines. . . . Not allowed to talk, gaze fixed straight ahead, they marched out of the gym. As alive as they had just been, they had now returned to being objects administered by the state” (2011, 210).

12 In Utopia in Performance, Jill Dolan argues that at its best and most human(e), performance offers a vision of unity, optimism, and equity. Dolan is interested in “utopian performatives,” theatrical “moments in which audiences feel themselves allied with each other, and with a broader, more capacious sense of a public, in which social discourse articulates the possible, rather than the insurmountable obstacles to human potential” (2005, 2). While all of us (the authors) have described moments in PCF in which this unity, even love, is palpable, Amie reminds us that the road towards what Dolan calls a “better later” requires critical and even uncomfortable work for those on the outside (7).

13 There is a space for deeper investigation into the quality and extent of the impact of attending PCF. Teya Sepinuck gestures towards the challenge of articulating how these performances change those who watch them; of audience members at her work with “lifers” she writes, “I know that many people said their lives were transformed. . . . But I think if you ask them what that actually means, they probably couldn’t tell you" (2011, 178).

14 This quandary is beautifully expressed by James Thompson, who emphasizes the inherent theatricality of our criminal justice system when he asks, “Does prison theatre . . . undermine the lurid spectacle of retribution or is it in danger of being a less explicit part of it?” (2004, 57).

Works Cited

Adams, Jessica. 2001. “‘The Wildest Show in the South’: Tourism and Incarceration at Angola.” TDR: The Drama Review 45 (2): 94–108.

Alexander, Michelle. 2010. The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. New York: The New Press.

Brown, Michelle. 2009. The Culture of Punishment: Prison, Society, and Spectacle. New York: New York University Press.

Cate, Sandra. 2008. “‘Breaking Bread with a Spread’ in a San Francisco County Jail.” Gastronomica 8 (3): 17–24. Accessed December 15, 2017.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/gfc.2008.8.3.17.

Chammah, Maurice. 2015. “Prison Plantations: One Man’s Archive of a Vanished Culture.” The Marshall Project. Accessed June 1, 2018. https://www.themarshallproject.org/2015/05/01/prison-plantations.

Davis, Angela Y. 2003. Are Prisons Obsolete? New York: Seven Stories Press.

DiAngelo, Robin. 2012. What Does it Mean to Be White? Developing White Racial Literacy. New York: Peter Lang.

Dirks, Danielle, Caroline Heldman, and Emma Zack. 2015. “‘She’s White and She’s Hot, So She Can’t Be Guilty’: Female Criminality, Penal Spectatorship, and White Protectionism.” Contemporary Justice Review 18 (2): 160–177.

Dolan, Jill. 2005. Utopia in Performance: Finding Hope at the Theater. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Dworin, Judy. 2011. “Time In: Transforming Identity Inside and Out.” In Performing New Lives: Prison Theatre, edited by Jonathan Shailor, 83–101. Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Foucault, Michel. 1977. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Translated by Alan Sheridan. New York: Random House.

Goss, Justin, and Joseph Hayes. 2018. “California’s Changing Prison Population.” Public Policy Institute of California. Accessed August 1, 2018. http://www.ppic.org/publication/californias-changing-prison-population/.

Khan-Cullors, Patrice, and asha bandele. 2018. When They Call You a Terrorist: A Black Lives Matter Memoir. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Messerschmidt, Edward David. 2017. Change Is Gonna Come: A Mixed Methods Examination of People's Attitudes Toward Prisoners After Experiences with a Prison Choir. Diss., Boston University.

Nellis, Ashley. 2016. “The Color of Justice: Racial and Ethnic Disparity in State Prisons.” The Sentencing Project. Accessed April 10, 2018. https://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/color-of-justice-racial-and-ethnic-disparity-in-state-prisons/.

Nixon, Vivian, Patricia Ticento Clough, David Staples, Yolanda Johnson Peterkin, Patricia Zimmerman, Christina Voight, and Sean Pica. 2008. “Life Capacity Beyond Reentry: A Critical Examination of Racism and Prisoner Reentry Reform in the U.S.” Race/Ethnicity: Multidisciplinary Global Contexts 2 (1): 21–43.

Ross, Jeffrey Ian. 2015. “Varieties of Prison Voyeurism: An Analytic/Interpretive Framework.” The Prison Journal 95 (3): 397–417.

Schwan, Anne. 2016. “Postfeminism Meets the Women in Prison Genre: Privilege and Spectatorship in Orange Is the New Black.” Television and New Media 17 (6): 473–490.

Sepinuck, Teya. 2011. “Living with Life: The Theater of Witness as a Model of Healing and Redemption.” In Performing New Lives: Prison Theatre, edited by Jonathan Shailor, 162–179. Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Taylor, Diana. 2003. The Archive and the Repertoire: Performing Cultural Memory in the Americas. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Taylor, Julia. 2011. “Sculpting Empowerment: Theatre in a Juvenile Facility and Beyond.” In Performing New Lives: Prison Theatre, edited by Jonathan Shailor, 197–212. Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Thompson, James. 2004. “From the Stocks to the Stage: Prison Theatre and the Theatre of Prison" In Theatre and Prison: Theory and Practice, edited by Michael Balfour, 57–76. Portland, OR: Intellect Books.

Wilcox, Agnes. 2011. “The Inmates, the Actors, the Characters, the Audience, and the Poet Are of Imagination All Compact.” In Performing New Lives: Prison Theatre, edited by Jonathan Shailor, 247–255. Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Yosso, Tara J. 2005. “Whose Culture Has Capital? A Critical Race Theory Discussion of Community Cultural Wealth.” Race, Ethnicity, and Education 8 (1): 69–91.