Abstract

From the manipulation of space to confine, exclude, and discipline to the geographies of inequality fueling the prison industrial complex, mass incarceration is a deeply spatial practice. Community-led projects reveal how critical approaches to mapping can be used to counter dominant narratives about mass incarceration, or what Peluso (1995) terms “counter-mapping.” Reflecting on an ongoing Atlanta-based collaboration between ATLmaps (a community-focused geographic visualization platform), Common Good Atlanta (a college-in-prison higher education program), and Inner-City Muslim Action Network (a community organization), we ask: What kinds of stories can maps tell about the experiences of (post-)incarceration? We highlight three specific “story-projects” to showcase the potential of collaborative mapping to: (1) expose transcarceral practices, (2) educate) others about the situated experiences of incarceration and reentry, and (3) engage) seemingly disparate communities that shape and are connected through transcarceral experience.A note to our readers: We implore you to engage with the interactive maps embedded in this piece, and to use them as launching points for exploring other storytelling possibilities on the ATLmaps platform. We understand that we are challenging you to engage with our piece in ways that move beyond the traditional academic paper premised on text-based arguments, evidence, and conclusions; yet it is in clicking through the maps, digitally placing yourself in these virtual cartographies of georeferenced places and audio-visual narratives, that transcarceral voices come through in both literal and abstract ways.

Can I map a place I’ve never actually been to?

—Current student with Common Good Atlanta and inmate at Phillips State Prison, Buford, GA (July 2018)

Introduction

In March 2018, we visited Manuel’s Tavern for a meetup held by members of Atlanta Studies—a consortium of scholars, artists, community members, politicians, and more, all of whom are invested in teaching histories and shaping futures of Atlanta—to learn about current projects and generate ideas for future community-based projects. We attended as scholars representing ATLmaps.org—a community-driven, open-access platform that makes available all of Georgia State University and Emory University’s historical maps and allows users to stack digital layers of maps to create their own story-project. At the meetup, we heard from two men who spoke about their time as students in a college literature course. With great enthusiasm and in critical detail, the pair discussed issues of community advocacy, relating them to some of their most meaningful readings, including Shakespeare’s Hamlet, Paolo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed, and Michel Foucault’s Discipline and Punish. Their descriptions elicited nods of familiarity from the many attendees in the room who shared the common experience of reading these canonical texts as students and educators. Yet their nods were accompanied by an esteemed hush, likely because their experiences differed in one key way: the presenters read these books while incarcerated in Phillips State Prison.

The guest speakers are alumni of Common Good Atlanta (CGA), a college-in-prison program that “provides incarcerated people with broad, democratic access to higher education so they can develop a better understanding of both themselves and the societal forces at work around them” (CGA n.d.). Sarah Higinbotham started the program in 2008, advocating for education in prisons not as reform or rehabilitation but rather as a human right. A decade later, Common Good Atlanta now operates in three prisons (and counting) in the Atlanta area. Over 50 faculty members from Atlanta colleges and universities teach courses covering literary studies, political theory, mathematics, sciences, and creative writing, to name a few. The two alumni of the program, alongside Bill Taft (creative writing teacher and CGA’s codirector with Higinbotham), presented on CGA and their personal experiences of college-level education while incarcerated at this relaxed quarterly gathering. Sitting at the pub table, it was not lost on us that these men were, in many ways, the epitome of what the consortium aspired itself to be: engaged, proactive, scholarly, contributing. Committed to assisting the transition back into society for their fellow returning citizens and educating the local community, they were interested in collating a realistic, usable reentry resources guide based on their experiential expertise of the post-incarceration process. As project manager and content curators for ATLmaps.org, we asked the CGA folks (and by extension, their alumni networks) to collaborate with us.1

This piece is a reflection on an ongoing collaboration that has produced numerous community-based mapping projects about post-incarceration: CGA alumni have developed a Community-Sourced Reentry Resource guide and shared it as a data layer on ATLmaps; content curators have published corresponding resource-, demographic-, and narrative-focused data layers of the carceral system; and ATLmaps members have designed a “Storytelling through Mapping” workshop series that is being presented to CGA students at various state incarceration facilities. Our work encompasses statistics of failure, such as how certain neighborhoods are disproportionately targeted for incarceration or are cut off from reentry services, but also stories of reclamation, like this alumnus, a mechanic at an Atlanta tire shop. Teaming with CGA and the Atlanta branch of IMAN (Inner-City Muslim Action Network) has shown that collaborative critical mapping not only is about exposing problems associated with mass incarceration, but also, the critical engagement with and production of maps enables incarcerated students and returning citizens to locate knowledge and power in themselves and perceive their personal stake and social responsibility to care about and for the communities to which they return. In this way, mapping can be a celebratory pursuit, as it foregrounds participatory alliances and imagines possibilities for future community growth.

Working in concert with these educators, advocates, and returning citizens has taught us that maps can be useful tools for exposing unequal power relations and systemic injustice at multiple scales, provided that they do not reproduce the very systems of oppression they are intended to disrupt. We argue that, in addition to exposing the injustices and disparities produced through mass incarceration, community-based “counter-mapping” can be employed to push against the boundaries of carceral power, creating new spaces and opportunities for public engagement and education beyond reformative models. Enacting the real potential of the unique stories maps can tell, our teaming up has also spurred a series of ongoing and future ethnographic oral history projects rooted in our commonality of being Atlanta residents. Ultimately, our work seeks to illuminate how the power to think geospatially is a democratizing force, in which local community residents and returning citizens are not only mutually inclusive, but also are co-beneficiaries.2

Mapping the Transcarceral

Conceptual Frameworks

Our use of the term “carceral” to describe the entangled spaces, practices, and cultures of incarceration emerges out of Foucault’s use of the term in Discipline and Punish (1977) and has been more robustly developed through the subfield of carceral geography.3 Despite lasting conceptualizations of prisons as “total institutions” (Goffman 1961) with stark boundaries that keep incarcerated people “out of sight, out of mind,” carceral geographer Dominique Moran (2014) argues that prisons are never fully removed from the broader societies in which they are situated (see also Farrington 1992; A. Davis 2003; Gilmore 2007; Baer and Ravneberg 2008; Morin and Moran 2015; Turner 2016). This idea of fluidity and the blurring of an inside-outside dichotomy is reflected in the concept of “transcarceral” space, introduced by Anke Allspach (2010) in her research on the transcarceral spaces of federally sentenced women in Canada. Building on Allspach’s work, Moran writes that the carceral encapsulates “something more than merely the spaces in which individuals are confined—rather, that the ‘carceral’ is a social and psychological construction of relevance both within and outside of carceral spaces” (Moran 2015, 87). Similarly, Gill et al. (2016) use the concept of carceral “circuitry” to account for the increasingly expansive, circuitous networks that link institutions through widespread penal policy, which has been termed the prison industrial complex (M. Davis 1995; A. Davis 2003; Gilmore 2007).Mapping transcarceral experiences in the metro Atlanta area provides a unique opportunity to espouse what Nancy Peluso (1995) has termed “counter-mapping”: a method of geolocating the spaces, data, and narratives that upset dominant perceptions and discourses about society and the members who comprise it. We regularly employ the term “counter-mapping” to reflect a methodology that presently sits between community mapping and “participatory action mapping” (Boll-Bosse and Hankins 2018)—one that encourages community participation of all kinds and all capabilities, but which also recognizes and strives to activate the potential of mapping as a critical, political tool to affect change. As Boll-Bosse and Hankins explain, simply encouraging anyone to participate in mapping projects does not always ensure the democratization of knowledge (2018). Anchored in Peluso’s (1995) idea of counter-mapping and further inspired by Judith Butler’s (2004) call to critique the “frame” of humanity—who is perceived and viewable, who is permitted inside the frame of recognition and therefore eligible for communal empathy, and who conversely is condemned to be peripheral, outside the dominant frame of the human4—our project not only seeks to expose the entrenched systems of jurisprudence and culture that purposefully dehumanize formerly incarcerated persons, but also, and far more importantly, to elevate the under-told stories of returning citizens’ reentry to society. To be clear: while we see the importance of situating our mapping projects within the established scholarly literature of carceral studies, this is not the primary discourse community we hope to engage in our work. Rather, in an attempt to disrupt the dominant power-knowledges of state, media, and academic institutions, we are purposefully eschewing the traditional argumentative research article format here. Guided by this work of carceral studies and critical mapping scholars, we use collaborative mapping to explore how carceral culture stretches across space, permeating through everyday spaces and institutional networks, and to highlight a need for the geovisualization of reentry in particular.

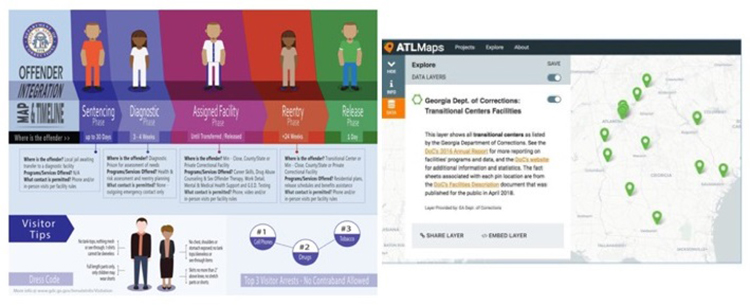

For example, as we show in Fig. 1, maps are conceptualized in diverse ways by different actors and to promote different agendas. An “Offender Integration Map & Timeline” published on the Georgia Department of Corrections’ (DoC) website places a notable emphasis on time rather than space, reading more like an infographic about process than a geovisual map showing the spatialities of reentry. When compared with the geovisualized locations of Georgia Department of Corrections Transitional Center Facilities, also sourced from DoC publicly available data, a more radial than processual story emerges.5

Mapping transcarceral geographies in the US context offers another method of showing how the carceral permeates and is embodied far beyond traditional spaces and duration of incarceration. In other words, even after release, an individual’s mobilities continue to be shaped by their status as a formerly incarcerated person, perhaps most notably in the search for housing and employment (Pager 2003). This type of constricted mobility reflects a phenomenon Moran terms “post-release ‘re-confinement’” (2014, 2), and serves as a reminder that “release” from a correctional facility does not always include the release of the tight grip of institutional power (Crewe 2011; Foucault 1977).

Historical Contexts of Mapping

Before elaborating further on the potential of digital mapping, we must first recognize that mapping—as a tool, technique, and epistemology—is inextricable from the historical and political processes that have shaped incarceration at various scales. In particular, mapping has been a vehicle for discriminatory racial science; at the turn of the twentieth century geographers were preoccupied with mapping the world according to race, using environmental characteristics like climate to explain characteristics of race (Livingstone 1992; Kobayashi 2014). As Amber Boll-Bosse and Katherine Hankins (2018, 320) explain, there are always “power relations embedded in and reflected through the map-making process and in maps themselves.” This is especially evident in the historical use of mapping as a colonial, boundary-forming tool to claim territory, demarcate property, and name places, all of which have contributed to the systematic oppression and exclusion of particular groups.6 As our work demonstrates, maps are not only products; they are actors that make and reshape worlds, and who makes a map can be as important as what the map conveys at first glance (see Crampton 2010; Pickles 2004; Wood 2010).

Through its many forms (from mental or cognitive mapping to more traditional cartography), mapmaking has played a powerful role in shaping how different subjectivities and behaviors are interpreted, managed, and treated. Indeed, part of criminalization, as an extension of marginalization, involves everyday decisions about whose bodies, activities, and identities “cross a line” in a particular place, and it is clear that unequal rules around these boundaries of public and private space lead to uneven enforcement. The meaning and use of “public”—as both an adjective and a noun—is continually under negotiation. Although a deeper analysis falls outside the scope of this piece, critical approaches to the ways in which mapping reinforces white, patriarchal, and colonial definitions of “public” are undercurrents of this conversation. Along these lines, key questions we consider include: How are definitions of “public” shaped by Atlanta’s cultural histories and who qualifies under that imagined category?7 When a space or event is marked as public, who and what is deemed in place or out of place? And given those conditions, how do maps perpetuate crime and punishment along racialized, gendered, and classed lines? In the context of transcarceral spaces, distinctions between public and private are blurred. Moran’s (2014) argument about post-release re-confinement comes to the fore: returning citizens may be described as returning to “the public,” but their continued surveillance through state and legal institutions upon release exposes barriers to their participation in public life even after release.

Indeed, these are prescient times for heeding warnings from history. As we write this piece8, the state of Georgia wrestles with a deeply flawed carceral system with 1 in 13 Georgians currently incarcerated (Georgia Center for Opportunity 2018) and is in the throes of attempting correlative efforts to redirect the misguided penal practices. Within the past decade, state spending for correctional facilities has effectively doubled, with over $1 billion in state funds invested to address the growing prison population and 30-percent recidivism rate (Boggs and Miller 2018). Over the past eight years in office, Governor Nathan Deal (Republican) issued in unprecedented criminal justice reform, including legislation to keep nonviolent offenders out of prison, establish accountability courts, reform the cash bail system, and expand GED fast-track programs across Georgia.9 In the context of criminal justice reform, political initiatives related to reentry programs are of particular interest to metro Atlanta and serve to establish a rare bridge between increasingly contentious partisan lines. While Governor Deal has gained attention in the national spotlight for his reentry initiatives, his term will end later this year and Georgia will elect a new Governor, whose platform on incarceration and reentry programs will sit under the electoral spotlight.10 Regardless of party affiliation, politicians and other public officials recognize the primacy that continued successful reentry programs have in reducing crime, prison costs, and recidivism rates. However, focusing on prison reform and reducing recidivism does not necessarily dismantle the prison industrial complex or end mass incarceration; it merely changes its shape (Rodríguez 2006; True Leap Press 2016). Our work therefore shows the power of counter-mapping as a way to move beyond reform, equipping incarcerated and returning citizens with geospatial critical thinking skills, and in doing so, empowering them to create new imaginations of place, community, and belonging—an empowerment that itself becomes a resister of mass incarceration.

Counter-Mapping as Praxis

Without dismissing the violent and oppressive histories of mapping, we are steadfast in our chosen methodology of critical, reflexive mapping because we see its potential for disrupting hegemonic power relations and shaping landscapes of resistance, liberation, and justice. Following Common Good Atlanta’s approach to education first and foremost as a human right that should be accessible to incarcerated and non-incarcerated citizens alike (see also Evans 2018), our work rejects the justification of mapping in prison education programs as merely rehabilitative or an anti-recidivism strategy. Rather, our work endeavors to showcase its potential as a material, embodied, and discursive exercise in critical thinking, regardless of where the education occurs. In the context of incarceration and reentry, critical and participatory approaches to mapping help reveal how carceral space permeates through and shapes everyday life in Atlanta: from CCTV cameras to food deserts to homelessness. Visualizing these transcarceral spaces exposes deeply rooted social problems that continue to fuel mass incarceration while also refuting the assumption that incarcerated people are isolated from the communities in which they are situated.

Geographers, by definition, are disciplinary experts on the concepts of space, place, and time, and practitioners of varied spatial methods of mapping and geovisualization. Yet it should be evident that incarcerated populations also hold unique and equally valuable geographical skills. By necessity and circumstance, prisoners are acutely aware of spatiality (restrictions, openings, access, territory, private, public, for instance) as well as temporality (“doing time”; Moran 2012). As we were reminded by Common Good Atlanta alumni at the Atlanta Studies meeting, while scholarly theorizations of (trans)carceral space have emerged only over the past few decades, prisoners have held the experiential, embodied knowledge (if not the theoretical language) of these blurred geographies for much longer. Teaching critical mapping in and out of prisons is one way of turning this experiential spatial knowledge into opportunities for redefining, reimagining, and reclaiming spaces.

This spatial awareness is reinforced in our Storytelling through Mapping workshop with CGA students at state incarceration facilities, hearing students’ revelations about the relationship between prison architecture and emotion as well as their debates about the constructed geopolitical boundaries of Atlanta as a city. For example, the topic of gentrification is brought up multiple times by CGA students in our workshop as we discuss how maps tell stories. The men in the classroom immediately relate how the prohibition of particular acts and behaviors are spatially conditioned and shift depending on who occupies, owns, and governs said spaces: prosecutions vary depending on county, city, and state boundaries; private property lines demarcate where bodily presence (versus behavioral act) is considered a trespassing crime. With keen insight and perspective, the workshop participants evince that the practice of counter-mapping situates returning citizens as essential partners in the vitality of the city, neighborhood, and community of which they are members. Similarly, in his piece on education in and beyond prisons, current inmate and CGA student David Evans (2018, 7) demonstrates how education has the potential to re-spatialize prison spaces from “negative place[s]” to what he feels is a more “positive” environment. Evans explains (8): “I’m often struck by the juxtaposition when I leave class and a guard yells at me and calls me ‘inmate’ with disdain in their voice. In class, I’m a human being; outside of class, I’m Frankenstein.” Evans (2018) further speaks of classrooms as creating “humanizing” bubbles within a dehumanizing institution, highlighting the transformative capacities of education in prisons when presented as a basic human right rather than rehabilitation. As we show below, the question addressed through these political and creative practices of “counter-mapping” thus becomes: How might Atlanta, among other places, be mapped differently if conceptualized through the voices and experiences of people coming out of prison?

Expose, Educate, Engage: Toward Participatory Action

With the mission of Mapping Stories of Your City, ATLmaps.org is an ideal space to focus our inquiries.11 As a digital, community-driven platform, the capacity of ATLmaps is 1. to be a repository of curated data layers (such as “Incarceration Facilities”) and historical maps from the archives of GSU and Emory (such as “Map of Atlanta: Negro Residential Areas 1962”) and 2. to be a user tool to search the repository, select multiple map layers to stack together, and save the piled maps as a story-project.12

Given the mechanics of the platform, the central question that we—as local residents, reentry advocates, and map curators—contend with at every step of our collaboration with incarcerated and returning citizens is: What kind of work does (counter-)mapping do in the context of incarceration and reentry in Atlanta?

Through our teaming with CGA and IMAN, we have discovered that maps “work” in three key ways: 1. maps expose transcarceral practices, 2. maps educate others about the situated experiences of incarceration and reentry, and 3. maps engage seemingly disparate communities that shape and are connected through transcarceral experience. To illustrate a counter-mapping praxis through our work with Common Good Atlanta and IMAN, we present three story-projects on ATLmaps: “Counter-mapping (Post-)Incarceration: Demographics,” “Counter-mapping (Post-)Incarceration: Resources,” and “Counter-mapping (Post-)Incarceration: Narratives.” The story-projects are all anchored by a common core map layer that foregrounds the experiential knowledge of returning citizens, titled “Reentry Resources, Community-Sourced,” as it was curated by returning citizens and their allies. In showcasing these three different story-projects, we illuminate the possibilities that emerge when multimedia layers are stacked together to show a spatial relationship.

Demographics Story-Project

Maps expose. When read and used critically, maps convey not just what sits at a particular location, but also what—and who—is excluded. Showing the spatial relationship between networks, services, and demographics is a powerful way of highlighting how the carceral extends beyond prisons. As we demonstrate, GIS-based platforms like ATLmaps tell a spatial story about mass incarceration in the broader context of the prison industrial complex, showing that place matters in terms of how crime is both perceived and perpetuated.

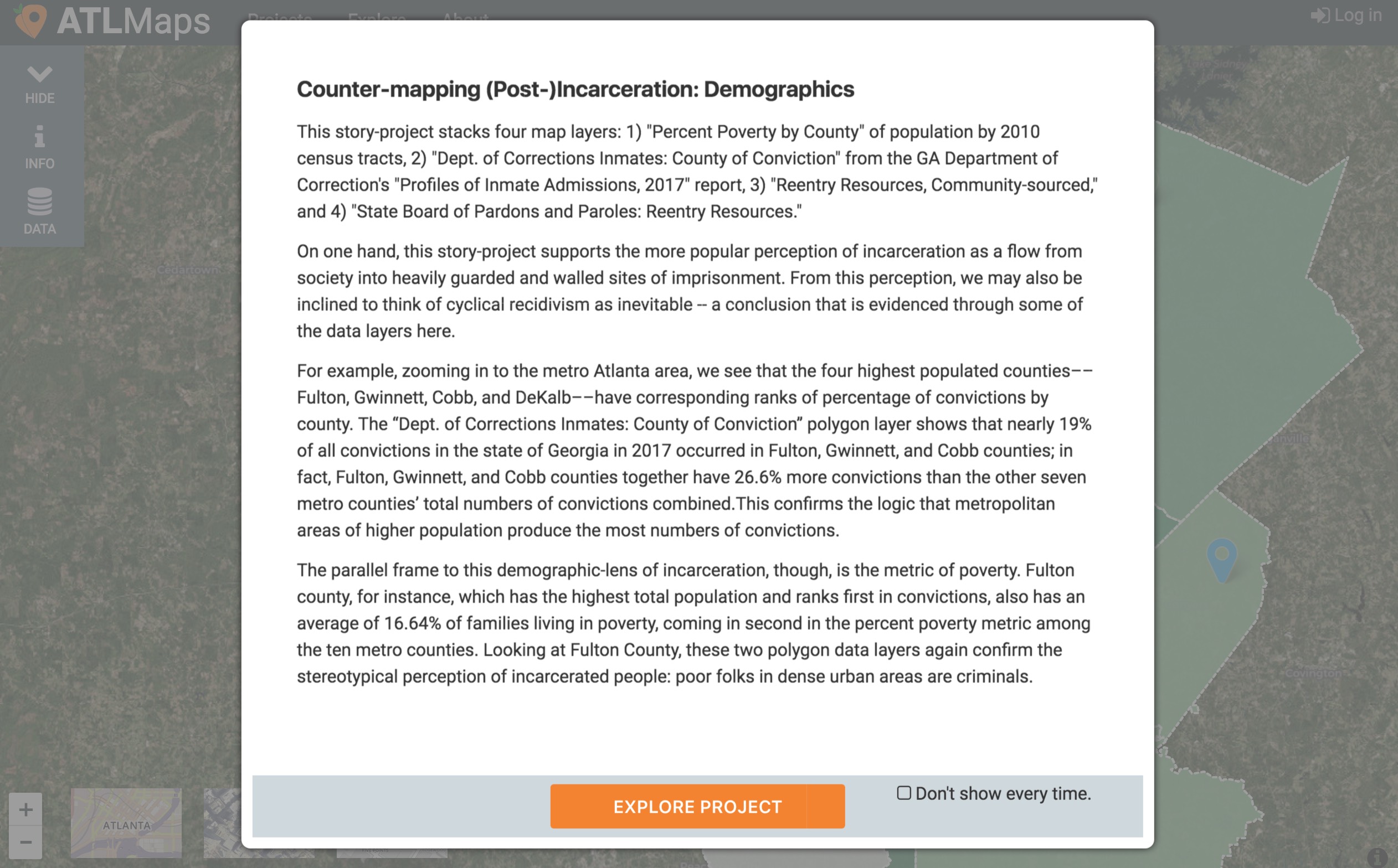

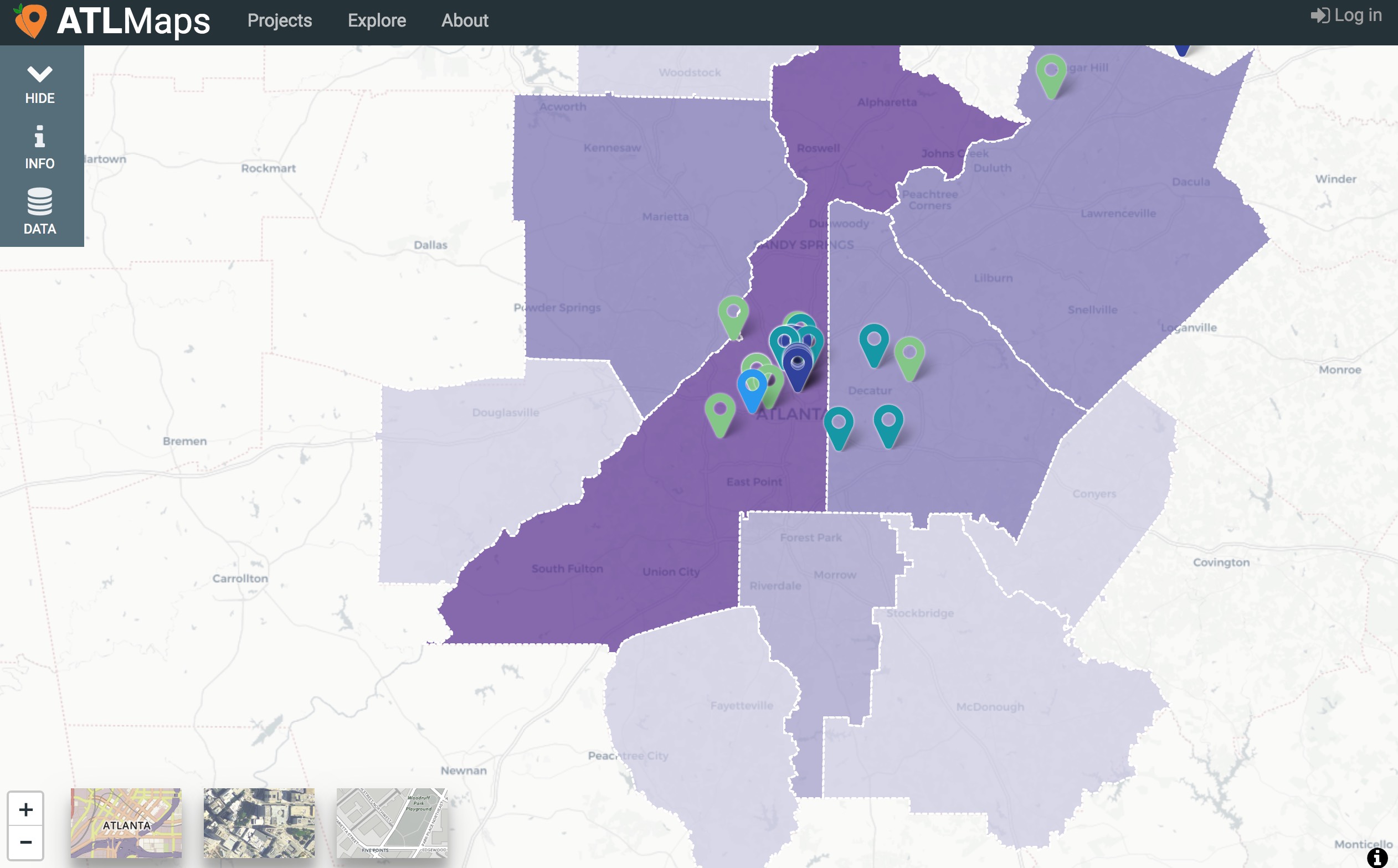

Our first story-project, “Counter-mapping (Post-)Incarceration: Demographics,” in part espouses a popular perception of incarceration as a flow from society into heavily guarded and walled sites of imprisonment. Following the established research that documents felons largely to be inner-city dwellers from impoverished neighborhoods of anemic socio-economic well-being (see, for example, the Vera Institute’s Incarceration Trends data tool), the “Dept. of Corrections Inmates: County of Conviction” data polygon layer testifies that the four highest populated counties—Fulton, Gwinnett, Cobb, and DeKalb—have corresponding ranks of percentage of convictions by county. The parallel frame to this demographic-lens of incarceration, though, is the metric of poverty. Layering the “Percent Poverty by County” data polygon layer with the “Dept. of Corrections Inmates: County of Conviction” layer, Fulton county supports the stereotypical perception of incarcerated people: poor folks in dense urban areas are criminals. On the other hand, through these maps we see that Clayton county—which ranks first in average percent of families living in poverty, but fifth in total population and rank of convictions—conflates the simple connotation of high population/high poverty/high convictions (see the story-project’s description on ATLmaps.org for the full data table).

Importantly, when we stack the data layers of “Reentry Resources: Community-sourced” and the “State Board of Pardons and Paroles: Reentry Resources,” we see that the counties of highest density of families in poverty and the counties with the highest numbers of convictions are virtual deserts of reentry facilities, programs, and organizations that aim to combat recidivism. Indeed, the few reentry resources that are rooted in neighborhoods prone to incarceration are not presently acknowledged on the State Board of Pardons and Paroles website; rather, programs such as IMAN and Empowering Men and Women on the Move for Reentry are mapped through community-based experiential knowledge (i.e., shown on the “Reentry Resources, Community-sourced” layer). We use different points, layers, and media to show discrepancies in what kinds of services are offered and, importantly, where they are located, and link this up to other layers (like transportation networks) to expose an issue with, for example, the problem of accessibility.

Resources Story-Project

Maps educate. Although popularly imagined as such, incarceration is not a unidirectional system. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, some 95% of incarcerated people in the US return to the public community after time served: reentry is a reciprocal social flow that demonstrates carceral conditions extend far beyond prison walls. In such, conditions of accessibility and mobility become another set of walls and bars of the US carceral system that, as Evans (2018, 12) notes, are in part contingent upon local community members. “Ultimately, incarcerated citizens bear the responsibility to shift the trajectories of their lives,” Evans states, “but society bears the responsibility to ensure they have the support and resources to do so” (2018, 12).

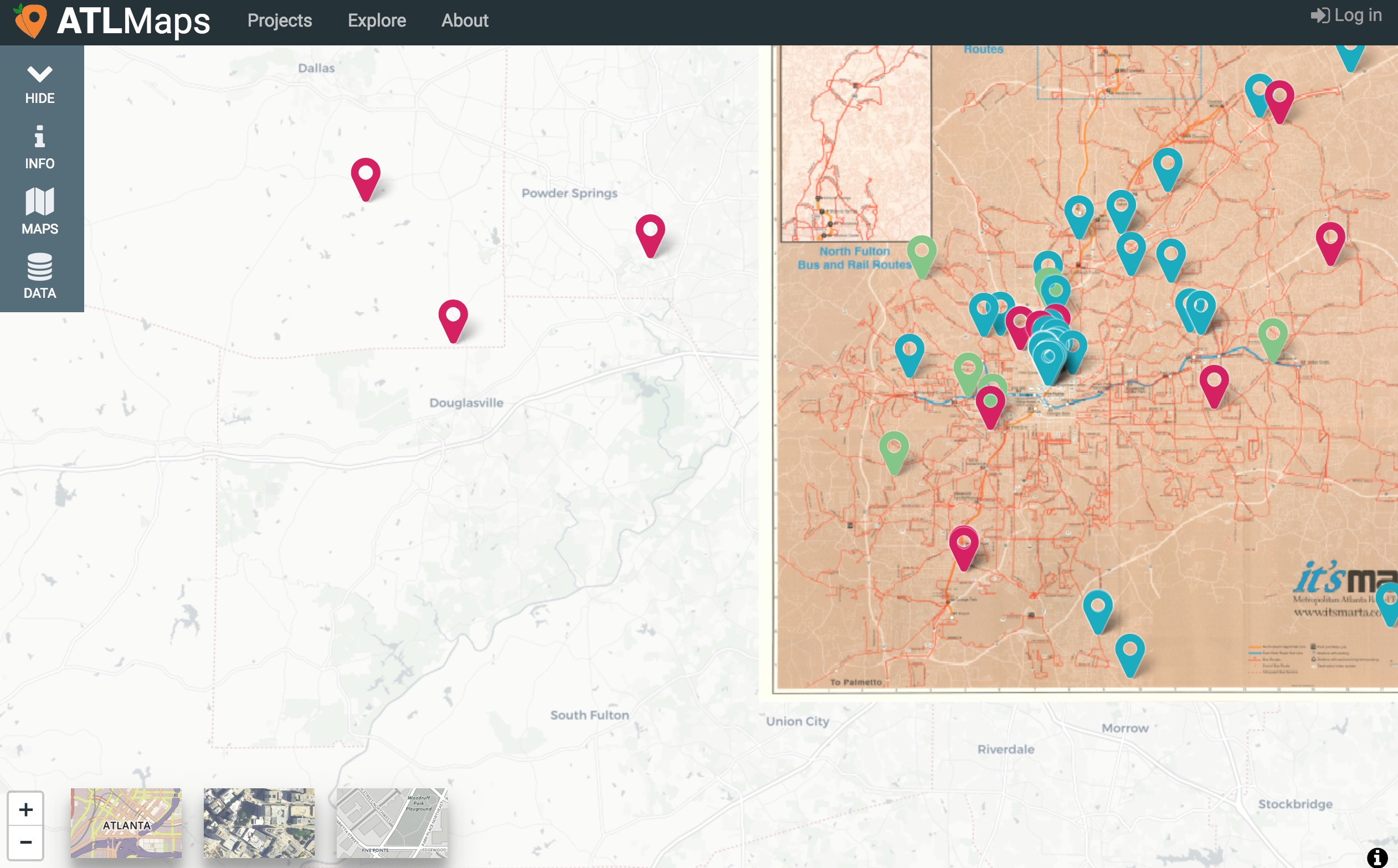

Our second story-project, “Counter-mapping (Post)Incarceration: Resources,” overlays public bus and train transit lines shown on the map layer “System Map of the Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority [MARTA], 2000-12” with the “State Board of Pardons and Paroles: Reentry Resources” data layer, the “Transitional Housing for Offender Reentry (THOR)” data layer (also sourced from the State Board of Pardons and Paroles), and the “Reentry Resources, Community-Sourced” data layer. Considering the State Board of Pardons and Paroles’ listed directory of “Transitional Housing for Offender Reentry (THOR),” we find that only 24 of the 85 Transitional Housing for Offender Reentry locations are within reasonable public transportation distance of reentry resources advertised by the SBPP. There are, of course, other transit systems throughout the state that are not represented on the MARTA raster map layer, such as county transit systems, rural bus lines, and other city-run bus systems outside of the greater Atlanta area. While returning citizens lodging in non-urban Transitional Housing for Offender Reentry sites may technically be able to use multiple systems of mass transit to eventually arrive at the various reentry service sites noted by the State Board of Pardons and Paroles, for many the journey is untenable as the transit time is so lengthy it overextends either normal business hours of reentry service centers or daytime transportation hours of transit systems.13 To be clear, we acknowledge that reentry resources not listed by the State Board of Pardons and Paroles exist throughout the state of Georgia; however, it is nevertheless telling that the state office chiefly responsible for enacting incarceration policies and practices offers such a geographically divorced catalogue of reentry services compared to its list of reentry housing.

Although we identified additional non-state websites with directories for state-based reentry services and resources, we were unable to find a map that showed their distribution throughout the city, let alone locate an online portal that offered interactivity. Because ATLmaps.org serves as a clearinghouse for thousands of map layers and spatial data about Atlanta, it is an appropriate online hub for people to locate important services like housing assistance, child support, food programs, health facilities, employment assistance, and treatment centers. Experiential maps may be more useful to returning citizens because they are created by people who have gone through similar experiences of incarceration and reentry. As shown through our core common layer (“Reentry Resources, Community-Sourced”), community-produced maps look much different than those drawn using state-derived data, highlighting how counter-mapping captures the very local, situated experiences of place upon reentry.

Stacked together, these maps show that incarceration is not sequestered to formal spatial and temporal distinctions; instead, those markers seep through the convicted person’s legal sentencing, permeating throughout what is colloquially known as “free society.” Perhaps counter-intuitively, this understanding of the extension of carceral spaces and practices is precisely where the liberatory potential of mapping emerges as it invites—and even necessitates—a dialogue about incarceration and reentry, directly undermining a univocal discourse about it.

Narratives Story-Project

Maps engage. Digital maps do not just show relationships at different scales and across different communities; they also have potential to build new relationships. Working on maps as a community-building practice can build support networks, promote advocacy, and mobilize activism, all of which are increasingly being explored through participatory action methodologies (Boll-Bosse and Hankins 2018). The maps produced through our collaboration with CGA and IMAN highlight individual, situated, and often first hand experiences while also linking those stories to broader community narratives, especially through the capacity to layer media such as video and audio clips.

Our third story-project, “Counter-mapping (Post-)Incarceration: Narratives,” stacks the “Reentry Resources, Community-Sourced” data layer with multiple data layers of reentry stories on top of the polygon data layer “Dept. of Corrections Inmates: Self-Reported Home County” of the 10 metro-Atlanta counties. The reentry stories data layers locate sites of labor for community betterment (“IMAN’s Green Reentry” data layer) and stories of reentry through narrative profiles of returning citizens (“Beyond the Walls: Reentry Success Stories (GA Dept. of Corrections)” data layer) and video testimonies (“Common Good Atlanta: Alumni and Teacher Interviews” data layer).

As demonstrated through the stories told by returning citizens embedded in this story-project, ATLmaps.org becomes a participatory action platform for community advocacy in its capacity to provide a (virtual, digital) space for these narratives of reentry. This narrative story-project highlights the potential for more participants and advocates to engage storytelling in an open-access geovisual format. We have chosen to focus on maps related to reentry for this piece, as it was the initial entry point for our collaboration with Common Good Atlanta and IMAN. However, our narrative story-project leaves room for more people to use the ATLmaps platform to tell their own story, and in doing so to engage the creative element of reinterpreting the city in addition to reinterpreting post-incarceration. Crucially, this too is a mode of reclamation and resistance, both of which are poignant embodiments (however informal and subjective) of agency and enactments of citizenship.

One of the most powerful aspects of mapping is that alternative, often hidden, stories can be told through geovisual rendering. This is where ATLmaps becomes most participatory and democratic as it brings together collaborations between incarcerated people, returning citizens, service-oriented organizations, local residents, and scholars. In our Storytelling through Mapping workshops in state prisons and transition centers, we discuss the double-edged power of maps and mapmaking, and introduce the idea of counter-mapping as alternative, equally viable and powerful histories, experiences, and knowledges. The mapping exercises encourage movement and collaboration, embracing haptic, emotional, and co-constituted knowledges as an attempt at disrupting disciplinary carceral power that otherwise constrains incarcerated bodies. To safeguard the students who participate in these workshops, we do not include names, biographical details, or other overt identifiers; however, despite this protective anonymity it is worth noting that the intellectual rigor, scholarly curiosity, spatial awareness, and humanist empathy that flourishes in this workshop is profound. For example, in speaking of the agency inherent in mapping local, place-based knowledge, one student asked, “Can I map a place I’ve never actually been to?” When all participants in the workshop sketched out their own “mental map” of Atlanta, state-run institutions were largely omitted from notation.14 Instead, markers of mobility (key thoroughfares and parts of interstates), sites of music production, family neighborhoods, social hang-out spots, and favorite places to eat dominated the self-styled maps. One participant showed his vision of Atlanta as the hip-hop epicenter of the music industry by drawing the side profile of the face of an MC over the “heart” of the city. As these examples show, when all parties function as allies to one another to work for the vitality of their community, new epistemologies emerge that discredit the fear-based actions to ignore or even avoid returning citizens.

Our mapping projects with community groups have become initiatives that we hope will further disrupt, or counter-map, expectations about transcarceral storytelling. Most importantly, our collaborators are not “prison mappers.” Although we recognize that their stories can never be fully separated from their experiences of carceral spaces and power, prison narratives are not the only stories or knowledges they are capable of telling; mapping offers an alternative way to explore alternative topics, places, and subjectivities.15 Through its openness to polyvocal stories, the “Narratives” story-project is available for people to tell stories about place in whatever way speaks to them, and through different means, from more traditional forms of georeferencing (pinpoints at latitude and longitude coordinates) to performative and aesthetic expressions (audio, video, poetry, graffiti, music). In doing so, the potential of counter-mapping becomes realized.

Reflections and Future Directions

Collaborative mapping is a process that requires reflexivity both in terms of reflecting on the past, but also looking toward the future. Our work on mapping transcarceral space through a focus on post-incarceration is ongoing. In addition to enjoying the benefits of building new relationships with community groups in Atlanta through map-based collaborations, we also recognize that inevitably, if unintentionally, we have made mistakes and exclusions along the way, some of which only became obvious once we began to put ideas into practice. In this final section, we reflect on our work to this point and use it to highlight future directions and considerations as we continue to engage narrative-based, participatory action mapping.

Technical Logistics

Staying current with ever-changing data, policies, and even borders presents opportunities and corresponding challenges (see La Vigne, Cowan, and Brazzell 2006; Rich et al. 2008). While our work draws partly on the lived experiences of (formerly) incarcerated people, we also rely heavily on web-based directories for correctional facilities and reentry services to establish base layers. Websites are not always updated to reflect changes; furthermore, some of the hyperlinks are defunct or redirect to unrelated (and often shocking!) material. Along with the need to ensure up-to-date data comes the need for ATLmaps curators to have the training required to monitor and adapt to these dynamic changes to ensure they are also reflected in the maps.

Both issues—the changing data and the need for trained personnel to monitor and adapt to such fluctuations—point to the challenges of sustainability and longevity in the context of community-scholarly mapping projects on incarceration and reentry. Just as the data are in flux, so too are the compositions of the groups involved, including formerly incarcerated people (who may have a more transitional lifestyle upon return), as well as scholars at ATLmaps (many of whom are undergraduate and graduate students and who may only be part of the working group for a short time period). This presents challenges for establishing trust between individuals and ensuring the longevity of the post-incarceration project. Future best practices might involve selecting longer-term members to maintain relationships with partnering groups, such as educators at CGA and project managers at ATLmaps, while also welcoming the new ideas and skills that accompany rotating, shorter-term participation.

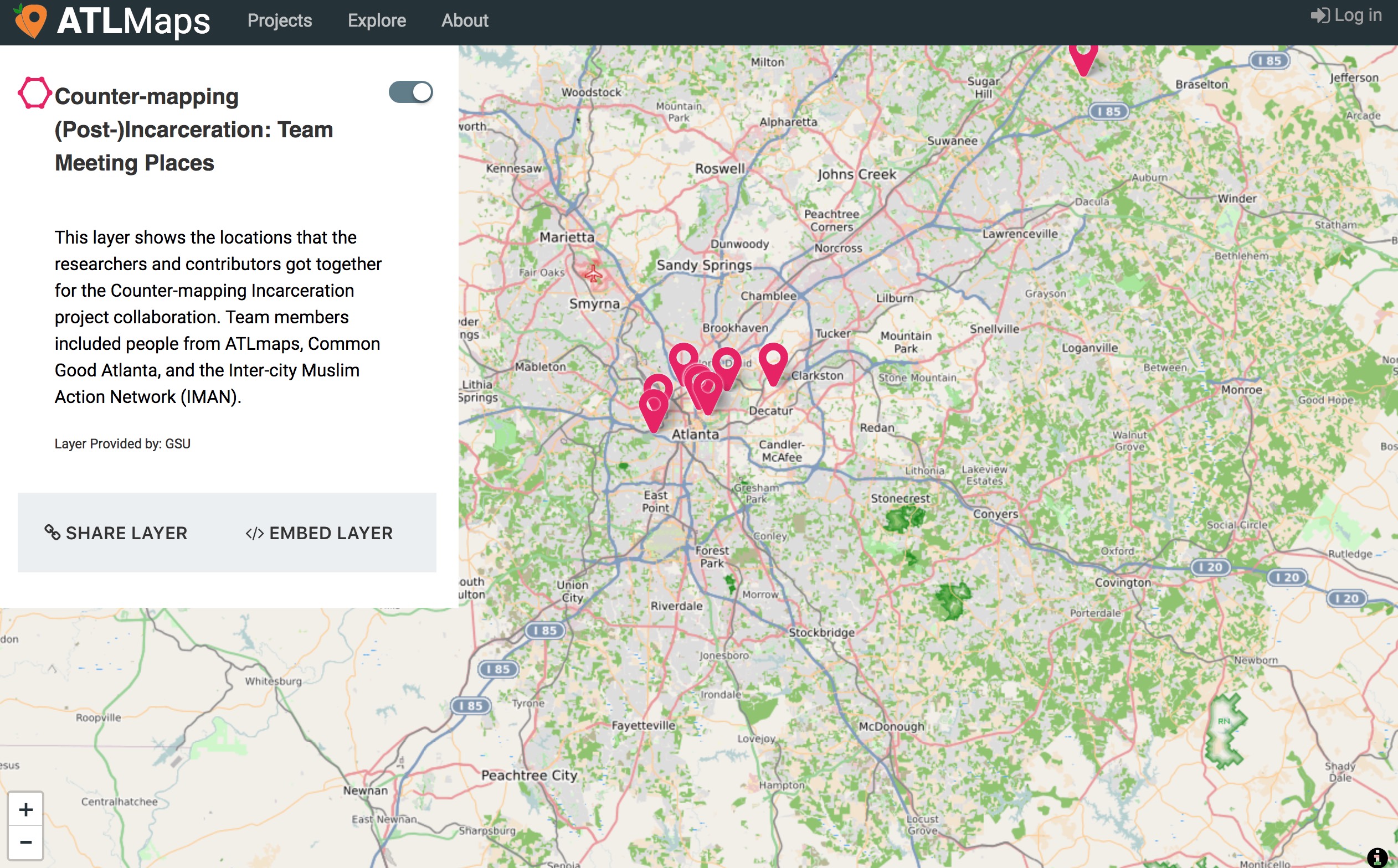

Gathering Places

Throughout this piece, we have highlighted how mapping operates as a political tool—one that is useful as a method to expose injustice and oppression and to mobilize change. But, as we have shown through our discussion of education and engagement, mapping is also a social activity. Bearing this in mind, an important consideration of participatory mapping is not just what is mapped and by whom, but how, where, and when the cartographic process takes place. Collaborative, community-based mapping embraces the benefits of in situ, face-to-face partnerships that encourage interaction with the places that sit at the heart of the issues being mapped. Indeed, the gathering places for such projects matter because place shapes how knowledge is produced, shared, and communicated.

Experimenting with meeting in a variety of places, therefore, offers diversity in terms of resources, participants, and ideas, all of which are shaped by the multisensory dynamics of each environment. As we show in Fig. 6 above, community members from ATLmaps, CGA, and IMAN have met at a number of sites across the metro-Atlanta area, ranging from a conference room at Georgia State University’s Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning to a family-run café in Westview (an area that, as one member reminded the group, is directly affected by the transcarceral issues we sought to map). Meeting in neighborhoods most affected by these carceral issues builds trust with community members and provides an opportunity to support local businesses and neighborhood organizations.

Connected to the selection of meeting places, accessibility is a complicated but important consideration for any critical mapping approach. Arranging meetings around accessibility means careful consideration of building access for people with disabilities, proximity to public transit networks, and ride sharing. But, as we have learned, accessibility goes beyond making sure people can physically attend the meeting sites. It also means offering flexible times that accommodate different types of schedules. The accessibility of communication is another important factor, and best practices for future participatory mapping should recognize that access to telecommunications (mobile phones, Internet access, and other digital media tools) may be limited or nonexistent, especially for recently released populations.

Representation and Authorship: Women’s Voices

Returning to the idea of mapping as a social and political process, it is important to reflect critically on the populations being represented and included in participatory mapping practices. Mapping continues to be a male-dominated domain. Likewise, although women (particularly women of color) are a fast-rising subpopulation in prisons, popular and scholarly portrayals of incarceration and reentry focus disproportionately on men’s experiences. To some degree, the skewing of representation can be explained by the availability of data and access, with women’s prisons often requiring an extra level of “protection” in scholarly and community engagement with incarceration. But greater commitment can and should be made to ensure women’s voices are heard and mobilized into advocacy. As Common Good Atlanta expands its higher education program into a women’s facility later in 2018, we see opportunity for establishing new connections and narratives that can be amplified through the ATLmaps platform. In addition to working with women in correctional facilities, these future efforts will also focus on outreach to women’s reentry programs (including religious organizations) and ask: How might (current and formerly incarcerated) women map their place-based experiences and knowledges when given the opportunity?

Conclusion: Mapping (for) Change

We imagine our maps as living organisms: these data layers are dynamic bodies with pulses and movements that not only reflect, but also enact, change. And because our platform is available online, with individuals having the ability to use our base layers to create their own maps, polyvocal stories about (post-)incarceration in the Atlanta area will continue to emerge in ways that both expose and resist the widespread injustices of the mass-incarceration system.16 One way to further engage with the changing characters of the city and the issue of (post-)incarceration is to make greater use of geographic information systems to build and layer multisensory stories, particularly through sonic media as another method of communicating change.17

Given the theme of this special issue, and the recognition that mapping is largely a method for producing spatial knowledge, our focus has been on the spaces of incarceration and reentry. Recognizing its inherent connection to space, however, future work might also explore more robustly how time might factor into mapping the transcarceral, beyond merely presenting timelines for reentry (recall Fig. 1). In addition to the more personal episodes and rhythms of confinement and reentry (doing time, keeping time, killing time, time served, waiting, or making up for lost time), there are much longer legacies of injustice that continue to haunt across seemingly distinct time periods. Connected histories of colonialism, slavery, capitalism, and patriarchy, for example, continue to determine who is most likely to be incarcerated or face systemic challenges upon reentry. Given the accelerated inequities of our current national sociopolitical moment, we challenge our readers to ask yourselves: How might we map these rhythms and legacies of transcarcerality, and how might we use this knowledge to affect change?

Our goal in this piece has been to show how we have leveraged critical mapping practices through the ATLmaps.org platform and teamed with returning citizens and community advocacy organizations to work through the complexities and imbalances of transcarcerality in Atlanta. We hope our efforts can inspire and even be replicated by other people interested in leveraging digital map creation as a bridge between incarcerated people, returning citizens, local communities, and perhaps even higher education institutions. Our work here seeks to provide a replicable, revisable, scalable template that others can use in any community—urban, suburban, or rural; in the Deep South, New England, the Heartland, or the West Coast—to manifest their own collaborative bridges. Hence, we offer not only our reflective expose, engage, and educate framework, but also our workshop materials (including our event flyer and lesson plan) for the Storytelling through Mapping workshop that we conduct in prisons and transition centers, and the source code for the ATLmaps platform through GitHub (https://github.com/ecds/ATLMaps-Client), so that anyone can initiate corresponding collaborations and use our materials and make them their own for the benefit of their communities.

Acknowledgements

This publication would not be possible without the steadfast support of the alumni and incarcerated students of Common Good Atlanta and the unparalleled intellectual and emotional work of Bill Taft and Sarah Higinbotham. We are indebted to Jay Varner, the Lead Software Engineer for ATLmaps.org, for his coding wizardry, and Brennan Collins, director of ATLmaps.org and the Student Innovation Fellowship at Georgia State University, for his keen and focused review. We are grateful to the ATLmaps Content Crew for their contagious enthusiasm and thoughtful teamwork. Finally, we thank the editors and anonymous peer reviewers for their generative insight on earlier drafts.

Notes

1 One of CGA’s closest nongovernmental liaisons is the Inner-city Muslim Action Network (IMAN), of which one of the CGA alumni speakers is a full-time employee. IMAN facilitates vocational training and provides community-led reentry services through transitional homes and faith-based mentorship. IMAN’s job skills training focuses on “green reentry,” a relatively new approach that teaches environmentally sustainable construction and building practices to put returning citizens on stable career paths tied to this growing sector of the economy. This approach to reentry is novel in that it not only provides housing and job resource skills to previously incarcerated individuals, but additionally benefits entire communities through the renovation of foreclosed homes and the utilization of green resources, as Manya Brachear in the Chicago Tribune reported in 2010. Since the establishment of their Atlanta branch in 2016, IMAN’s Green ReEntry program has been celebrated for already graduating two groups of students and completing its first housing project within the first year of implementation.

2 Our experiences working with and alongside currently/formerly incarcerated students is situated within a much larger historical context of prison education. Although a critical history of prison education is not the focus of our discussion here, it is important to recognize that contemporary philosophies about prison education (or, using an even more problematic term, “correctional education”) are part of a much larger genealogy with deeply entrenched roots in the Pennsylvania Prison Society of the late eighteenth century, the Quaker-inspired Pennsylvania/Philadelphia Model of incarceration, and Christian ideologies of penitence, including the prioritization of a “moral” education. For an extensive, critical history of prison education and the problems of prison writing, see Dylan Rodríguez’s Forced Passages (2006), Castro and Gould (2018), Karpowitz (2017), and Herzing in True Leap Press (2016).

3 See the Royal Geographical Society-Institute of British Geographers’ working group, Carceral Geography. For a more detailed theorization of the “carceral,” see Moran, Turner, and Schliehe (2017).

4 See Chapter Two, “Violence, Mourning, Politics,” in Butler’s book (2004). It is also worthwhile to note that dehumanizing rhetoric has become a heightened public phenomenon through the language used by President Trump, including calling some immigrants animals.

5 This is not to dismiss the importance of mapping out timelines and processes; rather, we use the comparison to show that there is a need for an expanded understanding of what “reentry maps” might portray, particularly through an emphasis on spatial relations.

6 This map-based oppression, including exclusion, displacement, and erasure, is often instigated through constructed categories of race, ethnicity, gender, class, ability, sexuality, and religion. For an Atlanta-specific example of how maps were used to erase and, consequently, displace poor black communities in Atlanta, see Gustafson’s (2013) piece on displacement and the racial state in the 1996 Olympics.

7 Mapping transcarceral spatialities of Atlanta must always be situated within the city’s complex historical geographies, including, but not limited to, colonial histories of slavery, displacement of Indigenous populations, 1906 race riots, civil rights activism, Ku Klux Klan occupation, the Atlanta Youth Murders, 1996 Olympics, gentrification, and charter schools—all of which have influenced how “public” is defined, defended, and resisted. For specific social histories of Atlanta, see Atlanta Studies, an open-access, digital network of publications by scholars and community members. We also invite readers to create an account on ATLmaps and explore our vast archive of historical maps and data layers that show the hegemonic misuse of mapping, such as this Home Owners’ Loan Corporation layer that depicts redlining in 1930s Atlanta (https://atlmaps.org/layers/e9i49).

8 The largest prison strike in US history is underway, demanding humane treatment in prisons.

9 These GED fast-track programs promoted by Deal are, however, connected to a network of charter school programs. It is therefore important to flag the problematic history of charter schools as part of a broader disinvestment from public services, a process intricately linked to the prison industrial complex and the marginalization of people of color, particularly black communities in Atlanta. For a more detailed account of the politics of charter schools, see Buras (2011), Fabricant and Fine (2012), Saltman (2012), and Watkins (2012). In addition, Deal directed the $13.7 million renovation of Metro State Prison in an effort to transform the formerly closed facility into a reentry hub to help former inmates return to the community. Due in part to Governor Deal’s criminal justice reform initiatives, Georgia’s political position on reentry has garnered not only the focus of various nonprofit and community-focused collaborative groups, but also has gained momentum in the legislative arena.

10 The nonpartisan nature of prioritizing such programs is evident through 2018 gubernatorial candidate Stacey Abrams’s (Democrat) Justice for Georgia Plan, which sought to expand the reentry programs presently implemented in Georgia.

11 ATLmaps is an interdisciplinary team of scholars from the fields of geography, computer science, urban planning, critical race studies, literary studies, sociology, and religious studies. Our work with CGA, IMAN, and other prisoner advocacy groups continues to move more fully into “participatory action mapping” (Boll-Bosse and Hankins 2018), with these groups having greater control over the entire mapping process, but does not dismiss the unique skills resources ATLmaps members bring to the table. Many of our team members are critically trained in geographic information systems (GIS) and other mapping techniques required to run such a platform, but also, more importantly, come to community-based projects with a critical understanding of how power relations shape maps and mapping practices. In addition to training in critical cartography and a committed interest in community-based issues, the ATLmaps cohort possesses institutional access to advanced mapping (e.g., GIS) technologies and software, high telecommunications capacities, and meeting spaces that would be useful no matter how large a role the members play in shaping future mapping projects.

12 See, for instance, “The Rise and Fall of Skid Row” and “Stadiumville.”

13 For example, if a returning citizen was living in a THOR residence in Columbus, GA, and needed to be at Atlanta Aid Health Services in downtown Atlanta by 1:30 p.m. on a Friday afternoon, s/he would have to walk over one mile, take a Greyhound bus, a MARTA train, and a MARTA bus, equaling a one-way transit time of three hours (detailed route estimate by Google Transit).

14 Mental mapping is an informal, cognitive style of mapping that involves inviting participants to draw maps (often by hand and from memory) of a particular place as they see fit, revealing very situated, cultural, and creative senses of place. For an example of mental mapping as a popular, community-based practice, see Becky Cooper’s Mapping Manhattan (2013).

15 While we recognize the long history and far-reaching vectors of carceral practices in Georgia that were (and largely remain) predicated upon racial inequities, we do not explicitly ask any of our collaborators or participants to map out the transcarceral as a critical race issue, though it is not a surprise when many end up creating their own narratives through mapping that engage with critical race issues. Racial injustice is endemic to incarcerated people and the carceral process, but we maintain that incarcerated and returning citizens should be more than spokespeople for racial injustice.

16 The ATLmaps team continues to work on usability and accessibility. At the time of writing, users can access all maps and layers existing in the platform; however, they still have to work with the ATLmaps team to add new layers and create larger projects. This involvement of ATLmaps members is in part due to technical hurdles still being resolved, but also speaks to the importance of having trained technicians who can assist community members with their technical mapping expertise.

17 ATLmaps member Steven Shields, for example, is planning a “religious sounds in prisons” project with incarcerated and returning citizens. See also Hemsworth (2016) for an account of sonic ways of knowing in the context of incarceration.

Works Cited

Allspach, Anke. 2010. “Landscapes of (Neo-)Liberal Control: The Transcarceral Spaces of Federally Sentenced Women in Canada.” Gender, Place & Culture 17 (6): 705–723.

Baer, Leonard D., and Bodil Ravneberg. 2008. “The Outside and Inside in Norwegian and English Prisons.” Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 90 (2): 205–216.

Boggs, Michael P., and Carey A. Miller. 2018. “Report of the Georgia Council on Criminal Justice Reform.”

Boll-Bosse, Amber J., and Katherine B. Hankins. 2018. “‘These Maps Talk for Us’: Participatory Action Mapping as Civic Engagement Practice.” The Professional Geographer 70 (2): 319–326.

Brachear, Manya A. 2010. “Re-Entry Program Gives Muslims Second, Green Chance.” Chicago Tribune, August 27. http://articles.chicagotribune.com/2010-08-27/news/ct-met-green-reentry-muslims-0827-20100827_1_muslim-converts-muslim-community-african-american-muslims.

Buras, Kristen L. 2011. “Race, Charter Schools, and Conscious Capitalism: On the Spatial Politics of Whiteness as Property (and the Unconscionable Assault on Black New Orleans).” Harvard Educational Review 81 (2): 296–331.

Butler, Judith. 2004. Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence. New York: Verso.

Castro, Erin L., and Mary Rachel Gould. 2018. “What Is Higher Education in Prison? Introduction to Radical Departures: Ruminations on the Purposes of Higher Education in Prison.” Critical Education 9 (10): 1–16.

CGA (Common Good Atlanta). n.d. “Our Mission.” Common Good Atlanta. http://www.commongoodatlanta.com/.

Cooper, Becky. 2013. Mapping Manhattan: A Love (and Sometimes Hate) Story in Maps by 75 New Yorkers. New York: Abrams.

Crampton, Jeremy W. 2010. Mapping: A Critical Introduction to Cartography and GIS. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Crewe, Ben. 2011. “Depth, Weight, Tightness: Revisiting the Pains of Imprisonment.” Punishment & Society 13 (5): 509–529.

Davis, Angela Y. 2003. Are Prisons Obsolete? New York: Seven Stories Press.

Davis, Mike. 1995. “A Prison Industrial Complex: Hell Factories in the Field.” The Nation 20: 229–234.

Evans, David. 2018. “The Elevating Connection of Higher Education in Prisons: An Incarcerated Student’s Perspective.” Critical Education 9 (11): 1–14.

Fabricant, Michael, and Michelle Fine. 2012. Charter Schools and the Corporate Makeover of Public Education: What’s at Stake? New York: Teachers College Press.

Farrington, Keith. 1992. “The Modern Prison as Total Institution? Public Perception Versus Objective Reality.” Crime & Delinquency 38 (1): 6–26.

Foucault, Michel. 1977. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Translated by Alan Sheridan. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin.

Georgia Center for Opportunity. 2018. “Georgia Prisoner Reentry Initiative.” Atlas Network. https://www.atlasnetwork.org/assets/uploads/misc/GCO_Prisoner_Reentry_Case_Study_Final.pdf.

Gill, Nick, Deirdre Conlon, Dominique Moran, and Andrew Burridge. 2016. “Carceral Circuitry: New Directions in Carceral Geography.” Progress in Human Geography 42 (2): 183–204.

Gilmore, Ruth Wilson. 2007. Golden Gulag: Prisons, Surplus, Crisis, and Opposition in Globalizing California. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Goffman, Erving. 1961. Asylums: Essays on the Social Situation of Mental Patients and Other Inmates. Garden City, NY: Anchor Books.

Gustafson, Seth. 2013. “Displacement and the Racial State in Olympic Atlanta: 1990–1996.” Southeastern Geographer 53 (2): 198–213. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26229061.

Hemsworth, Katie. 2016. “‘Feeling the Range’: Emotional Geographies of Sound in Prisons.” Emotion, Space and Society 20: 90–97.

Karpowitz, Daniel. 2017. College in Prison: Reading in an Age of Mass Incarceration. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Kobayashi, Audrey. 2014. “The Dialectic of Race and the Discipline of Geography.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 104 (6): 1101–1115.

La Vigne, Nancy G., Jake Cowan, and Diana Brazzell. 2006. Mapping Prisoner Reentry: An Action Research Guidebook. Washington, D.C.: Urban Institute Justice Policy Center.

Livingstone, David N. 1992. The Geographical Tradition: Episodes in the History of a Contested Enterprise. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Moran, Dominique. 2012. “‘Doing Time’ in Carceral Space: Timespace and Carceral Geography.” Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 94 (4): 305–316.

. 2014. “Leaving Behind the ‘Total Institution’? Teeth, Transcarceral Spaces and (Re)inscription of the Formerly Incarcerated Body.” Gender, Place and Culture 21 (1): 35–51.

. 2015. Carceral Geography: Spaces and Practices of Incarceration. Farnham, UK: Ashgate.

Moran, Dominique, Jennifer Turner, and Anna K. Schliehe. 2017. “Conceptualizing the Carceral in Carceral Geography.” Progress in Human Geography.

Morin, Karen M., and Dominique Moran, eds. 2015. Historical Geographies of Prisons: Unlocking the Usable Carceral Past. New York: Routledge.

Pager, Devah. 2003. “The Mark of a Criminal Record.” American Journal of Sociology 108 (5): 937–975.

Peluso, Nancy Lee. 1995. “Whose Woods Are These? Counter-Mapping Forest Territories in Kalimantan, Indonesia.” Antipode 27 (4): 383–406.

Pickles, John. 2004. A History of Spaces: Cartographic Reason, Mapping and the Geo-Coded World. New York: Routledge.

Rich, Michael J., Michael Leo Owens, Moshe Haspel, and Sam Marie Engle. 2008. Prisoner Reentry in Atlanta: Understanding the Challenges of Transition from Prison to Community. Emory University Office of University-Community Partnerships.

Rodríguez, Dylan. 2006. Forced Passages: Imprisoned Radical Intellectuals and the US Prison Regime. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Saltman, Kenneth J. 2012. The Failure of Corporate School Reform. New York: Routledge.

True Leap Press. 2016. “Black Liberation and the Abolition of the Prison Industrial Complex: An Interview with Rachel Herzing.”

Propter Nos 1 (1). https://trueleappress.com/2016/08/30/black-liberation-and-the-abolition-of-the-prison-industrial-complex-an-interview-with-rachel-herzing/.

Turner, Jennifer. 2016. The Prison Boundary: Between Society and Carceral Space. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Watkins, William H. 2012. The Assault on Public Education: Confronting the Politics of Corporate School Reform. New York: Teachers College Press.

Wood, Denis. 2010. Rethinking the Power of Maps. New York: Guilford.