Abstract

This essay explores the prison as an archive by focusing on an emerging digital humanities project about the history of prisons. The Washington Prison History Project (WPHP) began with the donation of two decades of records of prisoner activism; it includes an assortment of correspondence, self-published newspapers, photographs, and even a text-adventure computer game that was first designed in prison in the late 1980s and which the authors have recreated. The authors—a professor, a recent alumna, and two librarians—describe the origins and development of the project as a counter-archive of prison. Drawing on artifacts from the project, they argue that this alternate archive provides a means to teach, learn, and interpret the prison from the perspective of incarcerated people and their supporters and loved ones. A Counter-Archive of Imprisonment: The Washington Prison History ProjectPrison is many things. Most obviously, it is a place of punishment. But it is also a site of history and an archive. It is an archive that makes evident what anthropologist Michel-Rolph Trouillot (1995) described as the workings of power in the “production of history.” Like any archive, prison constantly produces, records, categorizes, silences, and limits access to information. The incident report that produces a parole denial, the sentencing report that further prejudices guards against a prisoner, the lieutenant’s instructions to restrict the person to solitary, the judge’s allocution that someone deserves no public sympathy and no chance of release, the criminal conviction that prevents someone from accessing public housing or the right to vote. The prison archive is a massive record of disposability. Though its archive is constantly being replenished and expanded, many people encounter the prison’s archives only through its residual documents: when media report on someone going to prison, getting out of prison, or being violated in prison.

Yet that is not the only archive generated through prison. Rather, incarcerated people and their free-world supporters and loved ones generate an alternate archive of experience, memory, and the materiality that accompanies it. This counter-archive interrogates the place of prison while imagining possibilities beyond it. The four of us have been involved in one such project, focused on the history of mass incarceration and prisoner activism in Washington State. The project is still in formation, and here we describe its component parts thus far, linking to our emerging online presence with artifacts from the archive. As a case study, our goal is to illuminate how the cultural production of incarcerated people meshes with digital humanities to reimagine, as Public’s call for this issue suggests, “new horizons of liberation and freedom” that traverse the carceral landscape.

Political Radicalism and Its Archive

In late 2015, Ed Mead contacted Dan Berger about donating his papers to the University of Washington. He had spoken in Berger’s classes previously, and the two were acquainted through prison activism circles. Mead is a longtime radical from the Seattle area who spent close to two decades in prison (1976–1993) for his involvement in the George Jackson Brigade, a clandestine anticapitalist group formed in the 1970s. Named after a Black revolutionary prisoner killed at San Quentin in 1971, the Brigade formed in the mid-1970s as an armed wing of radical movements in Washington State. Over the course of four years, Brigade members bombed a series of government or corporate buildings to protest prison conditions at the notorious Walla Walla state prison, the deaths of Red Army Faction members in German prisons, US militarism, and local employment disputes in Seattle. Like Mead, many in the Brigade’s small group had been previously incarcerated as young people for the kind of petty offenses that still send working-class people to jail or prison. Brigade members funded their activities through bank robberies, and it was one such robbery in 1975 that sent Mead to prison (Burton-Rose 2010; Mead 2015).

Once incarcerated, Mead did his best to undermine the prison system. With others, he organized strikes, published newspapers, and coordinated with outside activist groups to advance a radical critique of not just the prison system but the capitalist state that maintained it. Perhaps most dramatically, Mead cofounded a group called Men Against Sexism at the Washington State Penitentiary. Located in Walla Walla, the state’s oldest and meanest prison was at the time governed through rape. Aggressive prisoners regularly assaulted weak, effeminate, or queer prisoners as guards looked the other way—or, in some cases, encouraged it. “In most prisons, the primary contradiction is between the races,” Mead said in a 2012 interview in Berger’s graduate class. “In Walla Walla at that time, the primary contradiction was one of sexism. The way you established your place in the pecking order was by raping vulnerable, weaker, gay prisoners—or straight prisoners—and prisoners were bought and sold” (Mead and Cook 2012). Men Against Sexism worked to stop prison rape. Many at Walla Walla were armed at the time, and Men Against Sexism was no exception. Mead said they needed weapons to confront what he called the prison’s “toughoisie,” a carceral neologism to name the way tough guys functioned as Walla Walla’s bourgeoisie (Mead 2015).

Men Against Sexism lasted only a few years, and Mead was transferred out of Walla Walla—and for a time, out of state as well. Yet he never stopped working to organize prisoners as part of a broader opposition to racism, sexism, and capitalism. As with many imprisoned intellectuals (Rodriguez 2006), Mead was self-taught and highly accomplished as a jailhouse lawyer, editor, and journalist. One of his final efforts in prison was cofounding the Prison Legal News newspaper, which in 2020 will mark 30 years of continuous publishing.

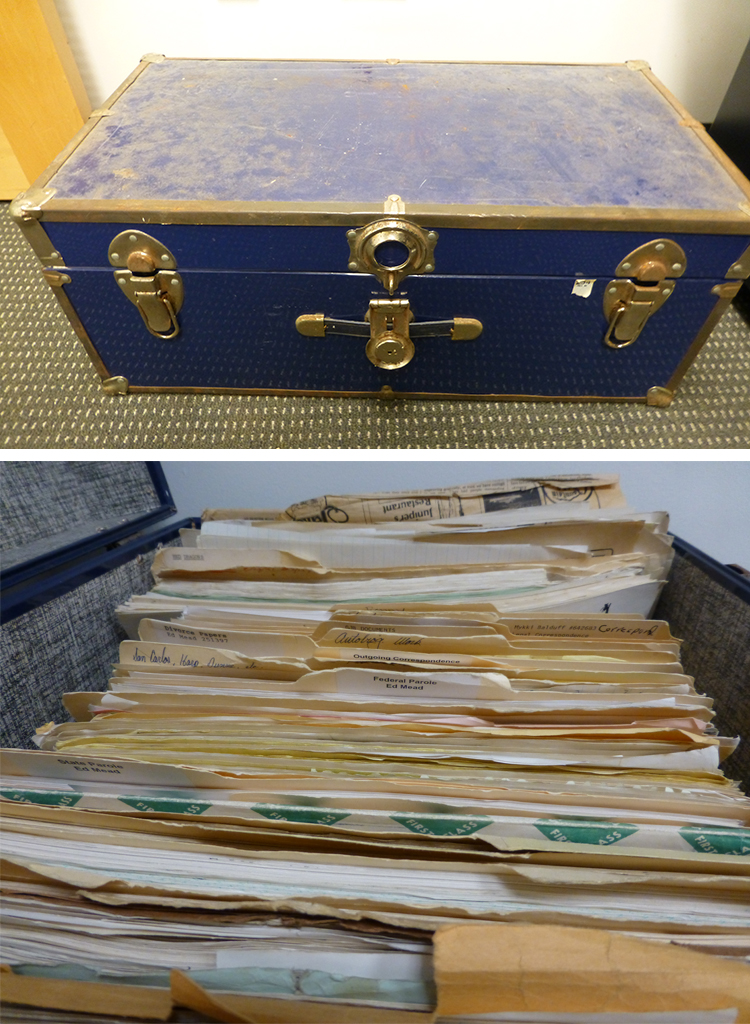

Mead reflected on these and other initiatives in his 2015 memoir, Lumpen, a book he first began writing while incarcerated. Once the book was published, he donated his papers to the University. Mead’s papers contain a trove of materials, including not just his own writings but those of dozens of other activist prisoners written in a time when the nation as a whole was locking up more people in more prisons for longer periods of time. Naturally, much of the material focused on Washington State, which has not garnered the kind of scholarly attention to its prison system that more populous states such as California (Berger 2014; Gilmore 2007), New York (Thompson 2016), and Texas (Perkinson 2010) have received. Yet Mead’s papers revealed the robust, dynamic nature of the archives incarcerated people themselves have created. They also inspired the development of a broader initiative to think through the meaning and significance of prison in Washington State from a grassroots perspective.

Facilitated by the open access mission of the UW Bothell library, Mead’s papers signaled the possibility of a broader archive. Our hope was to build on the examples of projects like The Knotted Line (an artistic and partly speculative history of imprisonment and resistance in California) and the Prison Public Memory Project (which began as a community history of a particular institution in upstate New York, now expanded to include a focus on Pontiac State Prison in southern Illinois) for the Pacific Northwest. Rather than processing Mead’s papers alone, the goal became a digital project that could provide a fuller, public accounting of the human magnitude of mass incarceration in the region as part of understanding its effects across the nation—as experienced by incarcerated people themselves. Thus the Washington Prison History Project was born.

Building the Washington Prison History Project

The WPHP connects the library, as both a physical and digital entity, and the classroom to larger publics within and beyond the prison system. Below we outline how these component parts have developed to date: first by considering the role of the library in providing the foundational infrastructure for the archive through a commitment to making information freely available to the public (i.e., open access) and pedagogically useful in the classroom. Next we analyze the technical components of developing a website for the archival materials. We conclude by outlining one of the most auspicious components of the archive: a text-adventure computer game (The Warden Game) that Mead designed in prison in 1987, which we have worked to recreate and make freely available through the project.

The Open Access Library

The UW Bothell Library is a key partner in the Washington Prison History Project. The library hosts the digital archive component of the project and provides the technical infrastructure for the archive. Library staff process, preserve, and make accessible all archived materials. Library staff scanned Mead’s papers over the course of two years, and library staff are currently working on metadata to describe these materials and enhance their findability. The materials in the first of seven boxes of Mead’s papers are now fully available in the online archive, with staff continuing this work. Staff also process oral histories, photographs, and other archive materials as they are contributed. Danielle Rowland and Denise Hattwig are based in the library and are both members of the project team. Rowland collaborates with Berger to teach archival research methods to undergraduates in a class focused on the WPHP archive, and Hattwig and Rowland teach various aspects of archiving, oral history, and description with undergraduates and graduate students. Hattwig is the archivist and digital scholarship consultant on the project and also manages library staff workflows.

In addition to staff and infrastructure, an essential aspect of the library’s contribution to the project is the library’s deep commitment to open access and the potential it holds for equity and furthering social justice efforts. As we know from Belmonte and Opotow (2017), “a morally inclusive orientation to archiving is enacted operationally both through procedural justice as acquisition policies and through distributive justice as the broad availability of archival material to all.” At the UW Bothell Library, open access is not only an approach to scholarly publishing, but extends to our digital scholarship and archiving practices as well. We strive to open up access to participation in all forms of knowledge production and scholarly conversations. The library’s alignment with open access has been ideally suited to the goals of the WPHP as we pursue a public accounting of the impacts of mass incarceration in Washington State.

Open archives are made possible by a key bit of institutional paperwork and its reworking—the Deed of Gift and related agreement forms. These bureaucratic forms are traditionally the site of language that transfers copyright from the donor to the university (or other institution). The university then controls and often monetizes donated materials. In the UW Bothell Library, however, donors retain all of their copyrights and intellectual property rights while allowing the library to make all materials openly available for reuse. The university thereby does not appropriate, nor profit from, the intellectual or cultural work of project partners, yet is able to further common goals by contributing to the availability and accessibility of information through infrastructure and information systems.Unconcerned with these institutional requirements for archive building, Ed Mead’s personal interest in donating his papers to the project was, as one might expect from his writings and history, unencumbered by legal and institutional concerns. When we approached him with the need for a Deed of Gift, he responded, “I don’t care about bourgeois copyright! You don’t have to worry about that.” He nevertheless willingly signed the Deed in order to make the donation and broader project possible within the UW Library standards.

These multiple and often contradictory perspectives can be challenging to navigate as individuals committed to social justice working in the context of state institutions. We are familiar with the problems inherent in archiving resistance movements against oppression in one state institution (prisons), in another state institution (the university). Libraries are clearly involved in institutional oppression themselves (de jesus 2014), and even more narrowly, “Archives are typically created by those at the top of the hierarchy: the non-marginalized, the power holders. Such archives ultimately reflect the stories of the elite and their ways of knowing and creating knowledge” (Shayne et al. 2016). Yet the archives literature also shows us that archives can be instruments of change, and can empower underrepresented and oppressed people and communities. Social justice is increasingly a core priority for archivists. Summarizing a comprehensive literature review, Punzalan and Caswell (2016) conclude, “This long-term engagement within the field suggests that social justice has become a central, if under-acknowledged, archival value.” Informed by this conversation, we seek to engage critical and reflective practices to counteract institutional oppression in the work of the WPHP, and situate the archive within a social justice framework. Honoring the resistance movements documented in the archive is important to us, as is the positionality of prisoners in our current system of mass incarceration, who are disproportionately working-class people of color and other marginalized groups.The library’s involvement has also anchored the project’s use as a teaching resource in the classroom. Students are involved in the work of the archive, some intimately so. Graduate and undergraduate students have produced metadata for documents to be digitized, in order to increase findability of the digitized documents by others (including, of course, other students). Several students have conducted oral history interviews with formerly incarcerated people, thereby becoming archive participants themselves. These oral histories have then been transcribed and made available on the project’s website.

In Berger’s regularly scheduled course on mass incarceration, undergraduate students explore the archive (physically and/or digitally) as part of a quarter-long research project. Students use the archive to carry out three learning goals: to analyze primary sources (investigating authorial intent, historical context, and content of archival sources); to understand how incarcerated people experienced the build-up of mass incarceration in Washington State; and to connect the issues those sources raise with current scholarship in critical prison studies. Outside of a particular class, two students have assisted Berger in developing the finding aid/series for the archive.

One graduate student involved with the archive secured a grant from the Simpson Center for the Humanities at UW that will allow librarians involved with the archive to attend the Digital Humanities Summer Institute with him, participating in an intensive course titled Race, Social Justice, and Digital Humanities: Applied Theories and Methods. Such student leadership bodes well for the future of the archive, as we continue to explore ways to apply anti-racist, counter-hegemonic pedagogy in its development.

The Online Presence, Part 1: Showcasing the Archive

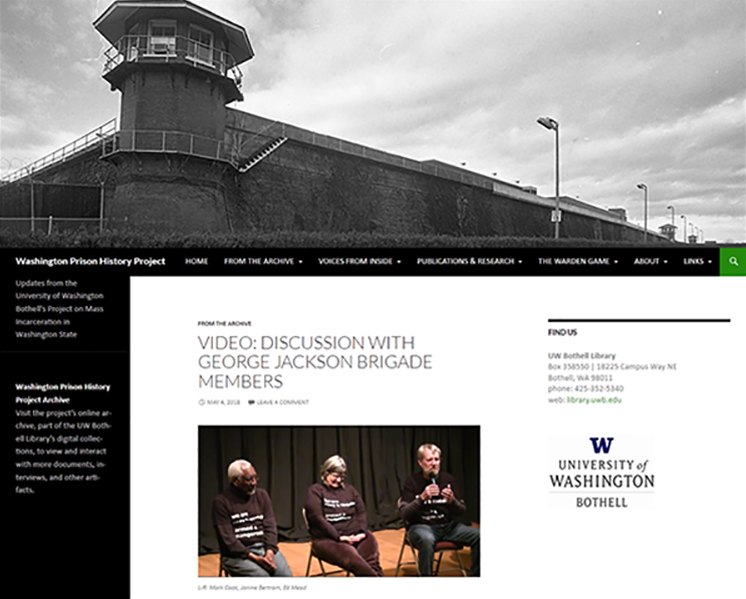

Once items are scanned, the library places materials in a CONTENTdm digital collection (www.diglib.uwb.edu/wphp). A valuable online repository, the platform does not have the usability features that make for easy navigation. We wanted to develop a public-facing website that we could use to highlight the breadth and depth of artifacts housed in the collection.

The Washington Prison History Project website is an essential component of the publicly engaged aspects of our work. Stand-alone archives can seem impenetrable to casual researchers, and often do not have the flexibility to interface with other resources. While the archive serves its own important functions, the site offers a broader and more contextualized presentation of our digital scholarship work that specifically supports our goals of participating in public conversations around mass incarceration.

Built on the open-source Wordpress platform, the website is an open and accessible community resource that serves as an interface to the projects, activities, and scholarship that the WPHP archive supports. The site’s primary template uses modern but largely traditional design elements intended to reach as large and varied an audience as possible by presenting a unified theme that is comprehensible and accessible. The design’s flexibility allows for individual pages or projects to be custom-built while still being framed within the larger site’s interface. The underlying information architecture is similarly flexible, allowing for easy introduction of new content by users in a variety of project roles and contributor contexts.

In addition to showcasing materials and projects from the WPHP archive, the website connects visitors to a larger universe of online resources on prisons and mass incarceration, especially in Washington State. The site features stories “from the inside,” publications and research, recent and upcoming events, as well as links to other useful resources that the site’s community of users may find meaningful.

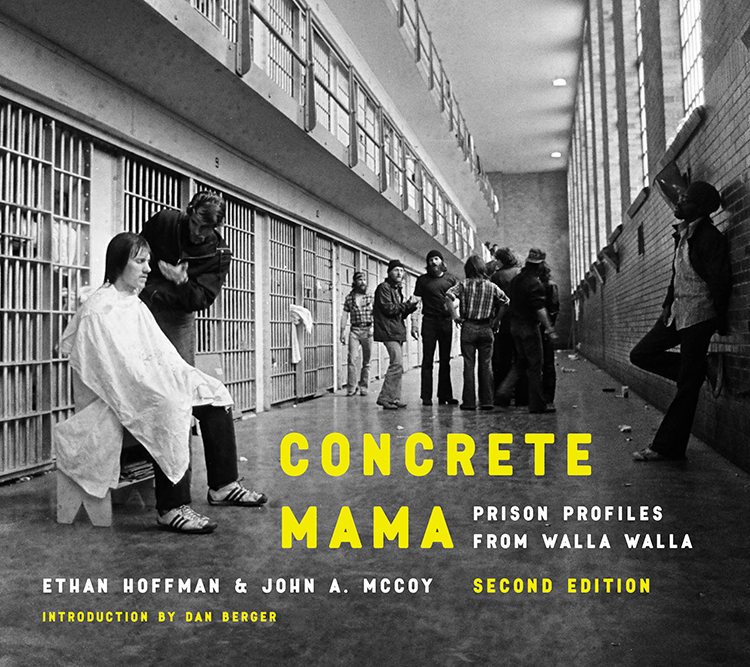

The website also allows us to highlight historical artifacts that the project has helped create, alongside those that it houses. For instance, our work on the project has led the University of Washington Press to reissue a 1981 book about the prison at Walla Walla. A unique photo-essay book, Concrete Mama is the result of journalists John McCoy and Ethan Hoffman (2018) being given nearly total access to the prison in 1978. The book had long been out of print, yet remained a stunning depiction of the prison in transition from a failed experiment in reform that saw prisoners exhibit a moderate degree of authority to the hyper-punitive locked down site it is today. Among other highlights, the book provides one of the only contemporaneously published accounts of Mead’s work with Men Against Sexism. In preparing the new edition, McCoy and Hoffman’s surviving relatives donated to the WPHP news clippings, unpublished photographs, and historical interviews from their time at the prison. Partly in recognition of the library’s role in the WPHP, the reissued edition was published in partnership with the UW Libraries.

The Online Presence, Part 2: The Warden Game

One of the most fascinating, and certainly the most unexpected, parts of the project has been the discovery of a text-adventure computer game about life in prison that Mead designed while incarcerated at the Washington State Reformatory in the late 1980s. The prison had recently introduced computers into the facility, allowing some of the civil society groups inside to use them in their efforts. (This was before the advent of the worldwide web; although prisoners at the Washington State Reformatory still have limited access to computers, they are denied internet access.) Ever the autodidact, Mead taught himself programming code. He made the game while incarcerated and recalls playing it with other prisoners.

Berger found the code in the archive in the form of a 20-page dot-matrix printout of original computer source code written in the BASIC language. Donea—a longtime tech worker who was then a graduate student at UW Bothell—worked to decipher its logic and committed to recovering its functionality and restoring it to some measure of playability.

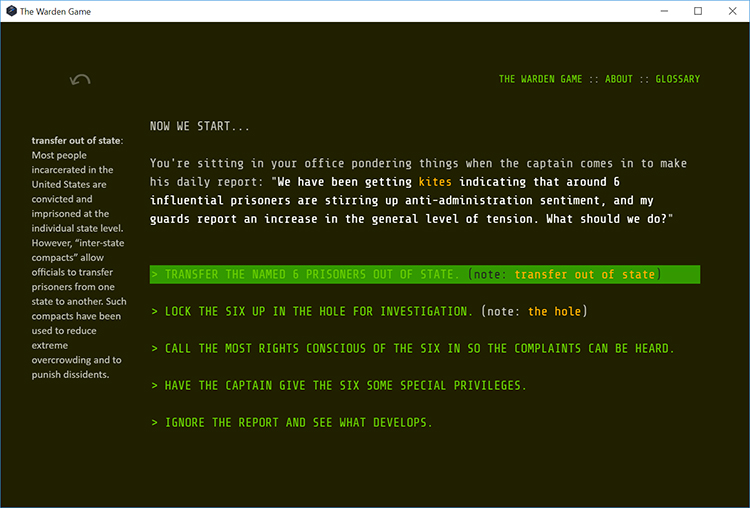

Some bit of historical context is in order, since the format is anachronistic to modern gaming. In a text-adventure game, the player reads text on a screen, is presented with choices, and chooses from a list of possible actions in order to continue. Given this format, it was possible to reconceptualize the game as a more modern “interactive story” and build an analog using a popular interactive story platform called Twine.

The resulting Warden Game is now available for playing online through the Washington Prison History Project website. We have designed it to be as faithful as possible to what would have been the original display, using monitor colors and fonts of the era to create an environment in which the gameplay mirrors its original version but takes into account modern interfaces, such as allowing for the use of a mouse or touch screen. The combined effect is that of a first-person experience that is immersive and pedagogically unique. The only changes we have made to the game are to fix typos or errors in programming, and to annotate the prison jargon that might otherwise be unfamiliar to modern players. After all, Mead designed the game for his own amusement and that of other prisoners. We determined that some translation of kites (unsanctioned letters between prisoners), the hole (solitary confinement), and perhaps even carbon paper would be necessary for non-incarcerated audiences in the twenty-first century.

The player of The Warden Game assumes the role of the warden of a maximum-security institution that has experienced some unrest on the part of both inmates and guards. In the era in which the game takes place, your prison is part of a larger state corrections apparatus whose structure and mission is in flux, and whose institutions are undergoing an overhaul and vast increase in footprint and funding. In the game, you are being presented with various demands, from insiders and outsiders both—prisoners, guards, state administration, families on the outside, community groups, the press. By choosing certain actions over others, you have the opportunity to see the outcome of those actions, including the reactions of others. You earn points for each choice you make. The game favors actions that reduce conflict, and so choices that support the peace and stability of the prison are worth more points than those that stir up additional conflict. Your main functional goal is to keep your job: if you get fired, the game ends immediately. The way you keep your job is to be neither too liberal, and risk outrage from the guards or legislature, nor too brutal, and risk sanction from a judge.

The game contains within it a number of assumptions about the warden’s role and the inherent limitations of the prison as an institution. The game’s pedagogical value lies in this situated position of its author, his ability to illustrate for the audience how power circulates in an institution constructed to at least seem rigidly hierarchical, how a variety of groups can leverage what power they do have in order to make great changes happen.

Conclusion

Designed in a maximum-security prison by a queer communist prisoner, The Warden Game reveals the inability of prison to constrain the creative outlets of people who are incarcerated. The Washington Prison History Project begins with that insight. The project aims to provide a fuller, public accounting of the human magnitude of mass incarceration in the region, as part of understanding its effects across the nation. We take it as an article of faith that currently and formerly incarcerated people and their communities constitute a public and a constituency. The archive highlights their voices, experiences, and creative workings as a way to assess the history and consequences of prisons in the region.

Given the restrictions on technological access imposed by prison, the online platform is obviously aimed at non-incarcerated publics. For these audiences, the project offers a hefty record of the civil society ambitions and creativity found inside of American prisons. Our work has consisted largely of making available artifacts created by incarcerated people. As the project develops, we are also deepening partnerships with community organizations—including those in prison—that might illuminate how people currently incarcerated in Washington State continue to imagine a wider freedom than prison can ever offer.

Prison generates a variety of counter-archives: in 2008, for instance, the artist cooperative Justseeds released a portfolio of posters, entitled Voices from Outside, in honor of the tenth anniversary of the prison abolitionist organization Critical Resistance. Mead himself used to coordinate a prison art website, in which he would sell artwork by incarcerated artists and ensure that the money went either to the artist or their family; in 2018, he also began another newsletter, The Kite, which will be archived at WPHP. Prisoner support organizations produce newsletters and encourage correspondence with incarcerated people. Podcasts like Beyond Prisons, Decarcerated, and Ear Hustle regularly feature the words of currently or formerly incarcerated people and their advocates. And a new generation of scholars is telling the history of prison reform and radicalism in American history, finding the sorts of unexpected rebellions evident in Mead’s papers (e.g., Haley 2016; Felber 2018).

The WPHP builds on these efforts. The project aims to do more than prove that “prisoners are people too.” Rather, the project affirms that any discussion of prison necessarily concerns the political radicalism and social organization of incarcerated people. It provides a social history of incarceration, emphasizing the collective experience of institutionalization—including its entrenchment, as record numbers of Americans have been locked up for ever-longer periods of time. The WPHP refuses to treat prison as a monolithic or static place. Much of the documents’ content explores difference within prison, especially along axes of gender, sexuality, race, and political perspective. A counter-archive might also, as it grows, serve as a clearinghouse of sorts: a place where the many communities harmed by prison can recognize, across their differences, a shared experience of resistance and resilience amidst the institutional violence of punishment. Countering the archive of imprisonment with one emphasizing the prison’s discontents, the WPHP provides documentary evidence of the robust social and political world that is formed behind and beyond bars.

Works Cited

Belmonte, Kimberly, and Susan Opotow. 2017. “Archivists on Archives and Social Justice.” Qualitative Psychology 4 (1): 58–72. http://doi:10.1037/qup0000055.

Berger, Dan. 2014. Captive Nation: Black Prison Organizing in the Civil Rights Era. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Burton-Rose, Daniel. 2010. Guerrilla USA: The George Jackson Brigade and the Anticapitalist Underground of the 1970s. Berkeley: University of California Press.

de jesus, nina. 2014. “Locating the Library in Institutional Oppression.” In the Library with the Lead Pipe. September 24. http://www.inthelibrarywiththeleadpipe.org/2014/locating-the-library-in-institutional-oppression/.

Felber, Garrett. 2018. “‘Shades of Mississippi’: The Nation of Islam’s Prison Organizing, the Carceral State, and the Black Freedom Struggle." Journal of American History 105 (1): 71–95. https://doi.org/10.1093/jahist/jay008.

Gilmore, Ruth Wilson. 2007. Golden Gulag: Prisons, Surplus, Crisis, and Opposition in Globalizing California. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Haley, Sarah. 2016. No Mercy Here: Gender, Punishment, and the Making of Jim Crow Modernity. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Hoffman, Ethan, and John A. McCoy. 2018. Concrete Mama: Prison Profiles from Walla Walla. 2nd ed. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Mead, Ed. 2015. Lumpen: The Autobiography of Ed Mead. Montreal: Kersplebedeb.

Mead, Ed, and Mark Cook. 2012. Interview by Dan Berger. Washington Prison History Project Archive. University of Washington Bothell/Cascadia College Library, University of Washington Libraries, University of Washington, Seattle, WA. http://cdm16786.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/compoundobject/collection/p16786coll15/id/432.

Perkinson, Robert. 2010. Texas Tough: The Rise of America’s Prison Empire. New York: Metropolitan Books.

Punzalan, Ricardo L., and Michelle Caswell. 2016. “Critical Directions for Archival Approaches to Social Justice.” Library Quarterly 86 (1): 25–42.

Rodriguez, Dylan. 2006. Forced Passages: Imprisoned Radical Intellectuals and the U.S. Prison Regime. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Shayne, Julie D., Denise Hattwig, Dave Ellenwood, and Taylor Hiner. 2016. “Creating Counter Archives: The University of Washington Bothell’s Feminist Community Archives of Washington Project.” Feminist Teacher 27 (1): 47–65. https://www.jstor.org/stable/femteacher.27.1.0047.

Thompson, Heather Ann. 2016. Blood in the Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and Its Legacy. New York: Pantheon.

Trouillot, Michel-Rolph. 1995. Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History. Boston: Beacon Press.