Abstract

The Carcerality Research Lab (CRL) was created as a space for knowledge production grounded in prison abolition. The faculty coordinators engaged the work of the CRL through Critical Race Theory and abolition pedagogy, and this article demonstrates the transformative power of this pedagogical approach. Student researchers were recruited from Chicana and Chicano Studies at California State University, Northridge, a Hispanic Serving Institution located in Los Angeles County, which is greatly affected by incarceration. The article focuses on the experiences of three student researchers and the impact of the CRL. All three students are Chicanas, first-generation college students from immigrant families, and they all have had a loved one incarcerated. Their involvement in the CRL has resulted in the three students making personal changes to live healthier lives, positively changing their relationships with family members because of newly gained knowledge, and engaging practices of knowledge production that further an abolitionist vision.Origins of the Carcerality Research Lab

In the Carcerality Research Lab (CRL), coordinated by professors Martha Escobar and Leticia Lara at California State University, Northridge (CSUN), we conduct research on issues of incarceration in California. We are currently working on a project examining the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation’s (CDCR) parole process for 138 Latinx1 “lifers.” CDCR employs determinate sentences, which are fixed time periods, and indeterminate sentences, which are time ranges. “Lifers” refers to both people who are sentenced to life and will never leave prison and people who serve indeterminate sentences and have the opportunity to reenter society if found suitable for parole. In the CRL we focus on the latter.

In California, individuals with an indeterminate sentence present themselves to the Board of Parole Hearings (BPH), made up of commissioners, who are appointed by the governor, and deputy commissioners, who are civil servants. Lifers with the opportunity for parole have a minimum eligible parole date (MEPD), which is the earliest date they can be paroled. For someone with a sentence of “15 to life,” their MEPD is when they complete 15 years of their sentence. The first suitability hearing usually takes place a year before their MEPD, and the hearing is conducted by a BPH commissioner and one to two deputy commissioners who determine whether the individual is ready to reenter society. If an individual is found unsuitable, which is overwhelmingly the case, the commissioners offer suggestions for improvement and schedule the next suitability hearing, which is between three and fifteen years later, depending on the commissioners’ assessment. Subsequently, the lifer can request an earlier hearing, which is decided on by the BPH.

As part of a previous study, Escobar worked with several Latina migrant lifers who had gone through parole hearings or were scheduled to attend. Throughout a person’s time in prison, a file is maintained that includes the individual’s background prior to incarceration, their behavioral history while incarcerated, psychological evaluations, and their parole plan if released. In the plan they are expected to demonstrate that they have a support network awaiting them to prevent recidivism, housing, job offers, and self-help programs available. To be found suitable, throughout the hearing they must demonstrate insight into their “life crime,” meaning that they must understand what it was about themselves that led them to engage in the criminalized activities that resulted in their life sentence, and remorse for their actions.

From this experience, Escobar observed that very few people were being found suitable for parole. The group of Latina migrant lifers stated that the process was overwhelming, especially for limited English speakers who face language barriers. Another issue migrants confront is the requirement to have two parole plans, which is an extremely daunting task to accomplish from prison, especially for people that have few connections to their countries of origin. During the hearing, individuals have a right to an attorney, who is usually appointed by the state since most people in prison cannot afford to pay to hire a private attorney. Drawing from Escobar’s experience and observations in her previous study, the new project being carried out by the CRL employs an intersectional approach to understand how interconnected axes of power, including race, class, gender, sexuality, nationality, and language inform the parole process for migrant and citizen Latinx lifers.

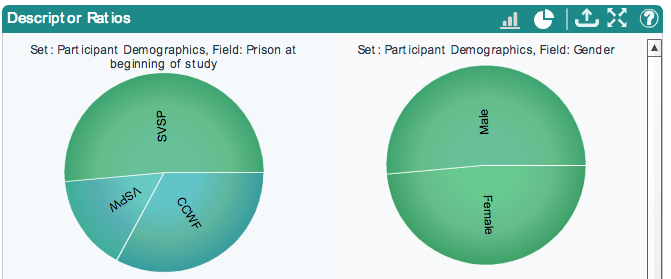

Every lifer parole hearing is recorded and transcribed and these documents are available to the public.2 Escobar obtained 332 CDCR parole suitability hearing transcripts from the CDCR Office of Research for 138 Latinxs, including 37 migrants, incarcerated in Central California Women’s Facility (CCWF), Valley State Prison for Women (VSPW), and Salinas Valley State Prison (SVSP) between September 2007 and May 2016. CCWF and VSPW were selected because they were the main women’s prisons that held lifers at the time3 and SVSP, which is a men’s prison, was included in order to provide a comparative gender analysis. The use of the parole hearing transcripts for our research provides important insight into factors that contribute to individuals’ life sentences, including histories of trauma, mental health issues, and access to resources. Drawing from court documents, individuals’ central files maintained in prison, psychological evaluations, and lifers’ testimony, during the hearings the commissioners delve into individuals’ pre-incarceration histories, behavior while in prison, levels of insight and remorse, and plans for the future. In addition to this wealth of information, the use of parole hearing transcripts is also productive because they offer an understanding of life in prison, including how individuals reinforce and at times challenge social norms and relationships of power related to intersecting axes of inequality.

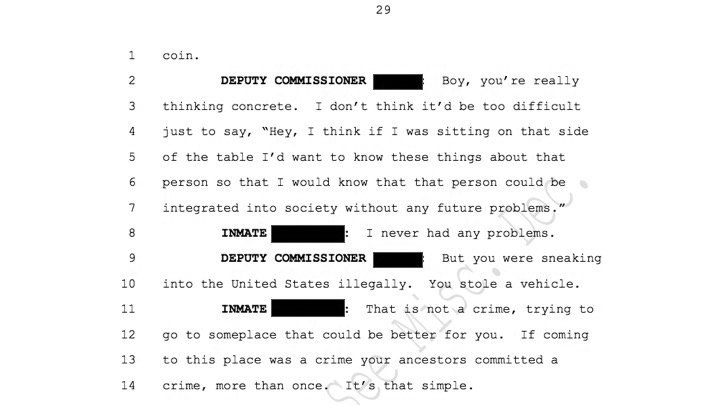

Moreover, part of our analysis incorporates an evaluation of commissioners’ biases, particularly in relation to race and ethnicity, class, gender, sexuality, and immigrant status. The transcripts capture moments during the hearing process where commissioners make subjective commentary that places value on individuals, and the transcripts capture how their biases inform their parole decisions. Finally, the analysis of the transcripts allows us to discern the uneven relationship between the stated mission of the parole process, which is to assess whether individuals pose a current threat to society, and the lived realities of lifers. Our research suggests that despite their preparedness, lifers continue to be denied parole because of their original offense.

The transcripts are currently being coded using Dedoose, a web application that facilitates collaborative group research. Because Dedoose is web based, we are able to collaborate virtually and also work independently. Dedoose allows for mixed methods research that is quantitative and qualitative. While our focus is mainly qualitative, it also allows us to quantitatively capture demographic information (i.e., nationality, gender, age, level of education, employment and relationship status at time of arrest, and county where they were sentenced). Dedoose also allows us to capture other factors that shape the experiences of Latinx lifers, including the types and amount of assistance needed during hearings, level of support by attorneys during hearings, how many lifers have histories of trauma (e.g., emotional, physical, and sexual abuse), how many have histories of drug use, gang membership, how the BPH uses the crime individuals were sentenced to life for to deny parole, outcomes of hearings, issues with parole plans, and amount of programming, which includes participation in self-help programs, paid and unpaid work, and any formal and informal education obtained during their incarceration.

The lab was conceived of in the summer of 2016, when Lara, an expert on mental health and early human development and a part-time instructor in the Sociology Department, approached Escobar, full-time faculty in the Department of Chicana and Chicano Studies. Having learned of Escobar’s research on the criminalization of Latina migrants, Lara approached her in hopes of developing community and expanding her research experience. She inquired about Escobar’s ongoing research and the possibility of collaborating. That summer the College of Humanities (COH) at CSUN announced the establishment of a research lab, which provided space for collaborative research among students and faculty. Motivated by Lara’s desire to collaborate and the COH announcement, Escobar applied and was selected as one of the faculty affiliates in the COH Research Lab. Escobar and Lara collectively designed the CRL during the summer and launched it in the fall of 2016.

Foundationally, the CRL is an abolitionist endeavor. The CRL is an extension of the activist work that Escobar began as an undergraduate student at the University of California, Riverside. Escobar and other student organizers joined the Schools Not Jails campaign of 2000 to mobilize against Proposition 21, the Juvenile Crime Initiative, which criminalized youth of color. Part of their activism involved researching the prison system. The Schools Not Jails campaign was informed by a growing group of activists, including many scholars, who were organizing against the expanding capacity of the state to cage people, particularly people of color. A watershed moment in the organizing was the Critical Resistance conference of September 1998, which took place in Berkeley, California. Critical Resistance is a national organization dedicated to “building a movement to abolish the prison industrial complex” (Critical Resistance 2018a), the PIC, which is a term used “to describe the overlapping interests of government and industry that use surveillance, policing, and imprisonment as solutions to economic, social, and political problems” (Critical Resistance 2018b). Over 3,500 people convened to analyze and conceive of ways to abolish the PIC. The organizing that students carried out against Prop. 21 was directly informed by the efforts of Critical Resistance and other abolitionist organizations.

Part of the analysis advanced by Critical Resistance is that incarceration is an extension of chattel slavery, and it makes this connection through the 13th Amendment of the Constitution, which maintains, “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.” The exception of criminality was used to criminalize the life conditions of black communities, and we witnessed an expansion of carcerality, especially of recently freed people. Once jailed or imprisoned, they were forced to labor for an extended period of time either for public projects or private individuals. Prison abolitionists draw from this critique and maintain that in addition to the United States making use of carcerality, meaning the physical confinement of bodies in carceral spaces to reorganize society to maintain white supremacy, it simultaneously refused to create the institutions necessary for black communities to sustain themselves and thrive.

The power of collaborative research to create transformative change is evident in the example of Critical Resistance. Many of the individuals that founded Critical Resistance and contributed to a global movement against incarceration are scholar activists who have dedicated their scholarship to understanding how carcerality, which includes prisons, jails, and detention centers, is employed as a way for society to organize itself. For example, one of the fundamental arguments advanced by abolitionist scholar activists is that the targeting of people of color for confinement contributes to the continuation of a society grounded in white supremacy. Some of these scholar activists work individually and others collaboratively, but they form part of a movement dedicated to creating a world without prisons. And this vision is both critically destructive and constructive. In addition to advocating for the dismantling of prisons and other carceral spaces, the prison abolition movement demands that we build democratic institutions that contribute to undoing existing relationships of power so that all communities have the opportunities necessary to thrive.

Today we are witnessing the impact of this movement in some of the reforms to the criminal legal system, including a reduction in incarceration numbers, as is the case in California. Abolitionists continue to carry out this work in various ways, and the CRL is a space envisioned as part of this movement. Escobar’s involvement as an undergraduate student activist, which was directly informed by Critical Resistance, led to her research on the criminalization experiences of Latina migrants, and this in turn led to the CRL and its current project on the experiences of Latinx lifers in California prisons. Thus, we conceptualize the CRL as not only being informed by Critical Resistance and other prison abolition organizations, but also forming part of the prison abolition movement and its vision of creating a world without prisons.

The abolitionist pedagogy employed in the CRL contributes to the researchers developing a deeper and more critical understanding of the criminal legal system and how it impacts society. The CRL provides an opportunity to reflect on how criminalization shapes our communities’ life conditions, and this understanding provides motivation to create personal, interpersonal, and structural change. Grounded in Critical Race Theory and abolition pedagogy, which we discuss further below, the pedagogical approach of the CRL is to engage in the cocreation of knowledge to challenge existing relationships of power. One of the most difficult aspects of prison abolition work is the ideological struggle to imagine a world without prisons. Carcerality is so entrenched in our society that it is very difficult to imagine organizing ourselves differently. Through the CRL, students and faculty engage in this imaginative labor and interact with the world differently because of our changed perspectives.

Participants

CSUN is a Hispanic-Serving Institution and, in the fall of 2017, Latino students made up 50.8% of the entire undergraduate student population (35,609) (CSUN Counts n.d.). This is significant as Latino communities make up approximately 40% of the people in California (Lopez 2014). Female identified students made up 58.2% and male identified students were 41.8% of Latino students enrolled at CSUN (CSUN Counts n.d.). 58.1% of all undergraduate students were eligible for Pell Grants, including 68.9% of Latino students (CSUN Counts n.d.). The purpose of the Pell Grant is to support students from low income families in obtaining a higher education, and thus Pell Grant eligibility is a good indicator of students’ socioeconomic status. Thus, the fact that almost 69% of Latino students were eligible for Pell Grants implies that the majority of them come from low-income families. Also significant is that CSUN is located in Los Angeles County, which has the largest jail system in the world and sends the greatest number of people to prison in the state (CDCR Office of Research 2017).4 Because the majority of our students are from Los Angeles County, many of them are impacted by issues of incarceration.

Student participants in the CRL are representative of these realities. Students were initially recruited in the fall of 2016 from the Department of Chicana and Chicano Studies’ majors and minors. This presented a significant advantage as students already entered the lab with some level of critical analysis. Several students demonstrated interest, but of this initial cohort, three students were consistent and dedicated to the research. The three students are Kiara Padilla, who was a double major in Psychology and Chicana and Chicano Studies and is now in the American Studies doctoral program at the University of Minnesota, and Paola Tapia and Rocio Rivera-Murillo, both double majors in Sociology and Chicana and Chicano Studies. All three students are first-generation Chicanas from working-class backgrounds, they come from migrant families, and importantly, all three have or had a family member incarcerated. Paola and Rocio continue to be involved in the lab and all three are coauthors of this publication. A second cohort was recruited in the early spring of 2018 and five additional students joined the CRL. We witnessed a similar pattern emerge regarding students’ backgrounds. Of the five new participants, three have a loved one behind bars.

Both faculty coordinators have backgrounds similar to the students. They are Chicanas, first-generation college graduates, they come from working-class migrant families, and have had loved ones incarcerated. The parallels between faculty and students have greatly contributed to our ability to identify with and understand each other’s experiences and struggles and to provide support to students.

Organization of the CRL

Initially, the CRL participants met weekly to train to conduct the research. In the first part of the training, we worked to develop shared meaning of the project by engaging several texts and other materials on various topics, including the centrality of race in the making of the US, the criminal legal system, the parole process in California, criminalization of Latinx communities, and prison abolition. These texts along with other resources (films, reports, websites, etc.) are made available through Canvas, the online learning management system used at CSUN. Canvas is utilized to assign tasks, provide training materials, and as a repository of the lab’s activities. To ground the group’s work in abolition, students were assigned Angela Y. Davis’s Are Prisons Obsolete? and viewed the film 13th, which provides a critique of the prison system originating in the enslavement of black people and its continuing devastation of communities of color. After establishing a commonsense understanding of prisons as institutions of domination, and thus the need to engage in abolitionist praxis, the group collectively read several transcripts and discussed important themes that arose. As everyone familiarized themselves with the parole process, we read through and revised the coding system using students’ input. At this point, we collaboratively trained on how to use Dedoose, which was a new platform for everyone involved; this process resulted in collaborative learning and growth for both faculty and students.

The cases the CRL engages are of lifers, meaning that the transcripts often depict significant levels of violence, including violence experienced by the lifer prior to incarceration, violence carried out by the lifer against others, and the violence exerted by the criminal legal system, including the parole commissioners, against the lifer. In order to support students to process so much pain, two students are assigned a lifer’s case and are responsible for coding all of their transcripts together. During our weekly meetings, we begin by discussing some of the difficulties they may have encountered reading the transcripts. We also check in with students regarding their studies and any other issues that they may be facing. These meetings have been extremely productive in establishing shared meaning and creating community.

In addition to fostering an abolitionist understanding, part of the purpose of the CRL is to encourage students, especially those impacted by issues of incarceration, to understand the significance of knowledge production and consider careers in research and education. To that end, we present professionalization workshops, and most have focused on career paths, including graduate school.

Pedagogical Framework

As part of the framework we use to understand our project, we draw from Critical Race Theory (CRT).5 CRT maintains that white supremacy is foundational to the creation of the United States, and thus historical, and that it is hemmed into every aspect of American society; institutional and structural white supremacy ensure the continued marginalization of communities of color (Crenshaw et. al 1995; Harris 1993). In other words, the basic framework that unites critical race theorists is an understanding that the US legal system disempowers people of color. Education is one of the institutions that was initially used in the subjugation of communities of color, either through the denial of education or the imposition of white supremacist education. Although white supremacy is seamed into the fabric of every US institution, critical race theorists advocate for the use of some of these institutions in freedom struggles. One such theorist is Derrick Bell, who maintains that CRT is simultaneously committed to “radical critique of the law (which is normatively deconstructionist) and . . . radical emancipation by the law (which is normatively reconstructionist)” (1995, 899). Within this discussion, Bell notes that “most critical race theorists are committed to a program of scholarly resistance that they hope will lay the groundwork for wide-scale resistance” (899). In other words, educational institutions are often a tool used in the subjugation of communities of color, but education as a site of knowledge production is an important tool for social justice.6

Drawing from this CRT understanding, in his article “The Disorientation of the Teaching Act: Abolition as Pedagogical Position,” scholar and abolitionist Dylan Rodriguez advocates for a pedagogy of abolition (2010). He maintains that the logic of prisons permeates every part of life; the US prison regime fundamentally shapes educational experiences and makes teaching possible. Rodriguez maintains that the logic of prisons informs school-based disciplinary practices “that imply the possibility of imprisonment as the punitive bureaucratic outcome of misbehavior, truancy, and academic failure” (8). He argues that “teaching is no longer separable from the work of policing, juridical discipline, and state-crafted punishment” (8); the “relative order and peace of the classroom is perpetually reproduced by the systematic disorder and deep violence of the prison regime” (16). He also makes the case that because the origins of prisons lie in the genocidal history of black enslavement, they are genocidal mobilizations of the US racist state. This places teachers in the position of being managers of genocide:

As teachers, we are institutionally hailed to the service of genocide management, in which our pedagogical labor is variously engaged in mitigating, valorizing, critiquing, redeeming, justifying, lamenting, and otherwise reproducing or tolerating the profound and systematic violence of the global-historical U.S. nation building project. (Rodriguez 2010, 17)

Because the logic of prisons is such an integral part of society’s common sense, Rodriguez notes the importance of educators and sites of knowledge production in struggles against the genocidal violence lived by predominantly people of color. The only conceivable position for educators is to engage in abolition pedagogy. From its foundation, the CRL was conceptualized as a space of knowledge production engaged in freedom struggles, and specifically in abolition. Some of the outcomes of this position are discussed below.

Another central aspect of CRT is the valuing and centering of the experiences and stories of people of color. Because people of color are the ones most directly impacted, they embody knowledge that provides important insight into the workings of white supremacist racism. In education, this counters the deficit paradigm that pervades and sees students of color, especially poor, working class, and first-generation students, as lacking and unprepared. Instead, CRT values experiential knowledge (Delgado Bernal 2002; Solórzano and Yosso 2002; Yosso 2005, 2006). It maintains that students of color have many talents, strengths, and experiences to contribute to their college environment and that educators can draw from these to promote students’ success.

Outcomes and Impact

The work carried out by the CRL has resulted in a number of outcomes. The research process was demystified for Padilla, Tapia, and Rivera-Murillo. They developed important research skills and submitted and presented parts of our research at two student conferences and an academic conference. They are now working in jobs that are aligned with their career goals. Padilla started a doctoral program in American Studies in the fall of 2018. Tapia and Rivera-Murillo are preparing to apply to graduate school. The students credit the CRL for providing guidance and support in this process.

In addition to these very tangible outcomes, what we want to emphasize is the impact of the CRL in struggles for social justice. Through our collaborative work, we have built a sense of community between students and faculty members. In the case of Lara, being a part-time instructor is often an alienating process; although they make up the majority of the faculty at CSUN, there is a sense of disposability in these types of jobs and often a disconnect to home departments. The CRL provided a space for Lara to feel a meaningful connection to a community on campus.

Because the focus of this piece is on pedagogy, we center the students’ perspectives. In March 2018 we conducted a group interview to assess the impact of the CRL on Padilla, Tapia, and Rivera-Murillo. All three noted important personal transformations as a result of our work. For example, they stated that their self-esteem improved and they recognize their intelligence, which they doubted prior to their involvement in the lab. Another area of transformation is mental health. Reading through the transcripts revealed patterns to the students that lead to poor mental health. As Padilla notes, “I think that reading the transcripts, you see the pattern of every single experience building and building and building towards them feeling like, ‘I can’t no more.’ And then you end up in this situation where you have no control. . . . You need to have control over yourself.” In the interview, they discussed tools they gained from the lab to care for themselves, including to set aside time for themselves, to avoid taking others’ problems with them, and to discuss and process problems with others. Overall, at the personal level, students feel more empowered.

In addition to personal transformations, the three students saw changes in their interactions and relationships with others. During the interview, Rivera-Murillo discussed how her siblings suffer from depression and how she did not understand their condition prior to being involved in the CRL. She tended to wonder why they could not just “get over it.” However, reading the transcripts and the role of poor mental health in the experiences of Latinx lifers provided Rivera-Murillo with a different and more empathetic understanding of her siblings’ situation, which helped improve their relationships.

Padilla also discussed how her relationship with her uncle, who was deported to Mexico after his incarceration, changed. She stated,

When I got to talk to my tío, who got deported to Tijuana from jail, I was like, fuck. . . . I empathized so much. I’m so thankful that I’m able to have these conversations, because I’m not judgmental. I’m like, “Oh really, and what were you doing? Tell me more about that.” And I think that makes them feel better. It’s like, “Wow, somebody’s actually listening to what I have to say,” instead of just, suppressing it. “I don’t want to see you as a criminal.” So, I think that it’s changed the way that I can have conversations about it, and not really feel like it’s a bad thing.

Because of her involvement in the CRL, Padilla is able to have conversations with her uncle about his experiences and contextualize them within a broader framework of the criminal legal system, and she is able to do so without making him feel judged or devalued for having a criminal record.

Finally, we believe that one of the most significant impacts is the fostering of an abolitionist vision among the students and beyond. Because of their family’s and communities’ relationships to the criminal legal system, the three students approached the research with a critical lens. However, reading the transcripts and the lifers’ narratives provided insight to understand that there are patterns in these cases—often people hurt others because they have been hurt; axes of power, including race, class, gender, sexuality, nationality, and language structure people’s experiences; interpersonal violence shapes and is shaped by state violence; and prison reform mostly results in further entrenchment of prisons in society. The development of these critiques led the three students to embrace an abolitionist identity and influenced their career paths. Tapia plans to become a social worker. During the interview she noted,

I think career-wise . . . it just helped me know that that’s what I wanna do. It kind of reassured me, this is the place for me. And even though I do really like the research and I would like to continue to do research with incarcerated folk, to me it’s like I rooted the transcripts to a deeper purpose for myself to kind of start from the point where we can prevent. . . . So, before it was, “What can I do to help people that are already in the jail system?” And I was looking at social work inside of the prisons. But I think it would be best for me to start in a place where you can prevent the trauma in the . . . not prevent the trauma, but help the kids cope with their trauma, so that it doesn’t lead up to a point where they have no other outlet for it, and they do something that would lead them towards incarceration.

In this example, Tapia embraces a constructive abolitionist identity who is determined to become a social worker to help individuals, particularly children and youth, learn to cope with the harm they have experienced before it leads to incarceration.

In the cases of Padilla and Rivera-Murillo, they are invested in continuing to conduct research and become professors. The following is an exchange that took place between them during the interview:

Padilla:Before research, I wanted to go back into my community and help in my community. And I thought that, for example, being a social worker or something in a nonprofit was gonna be a good choice. Because I was gonna be in the community. But now that I’m in research and I really love research, this whole notion of producing knowledge, that’s been very foundational to me wanting to continue. Because being like, “dude, I found this pattern,” and then being able to have that conversation with people of my community . . . kind of what you were saying before, Martha, being in academia, you’re in academia, but you’re still also part of your community . . . part of the knowledge that you’re producing. . . .Rivera-Murillo:You’re going to take back.Padilla:It is to take back to your community and try to make changes. . . . So, I see research as . . . I’m trying to find things that I can catch and theorize with academic language, so that other people in academia can fucking listen to you.Rivera-Murillo:And understand it.Padilla:And be like, “Look, this fucking matters.” But then at the same time, have those conversations with people in your family. Have conversations with people in your classes. And sometimes people in your classes are gonna have those same experiences, so then they’re gonna take that to their communities.Rivera-Murillo:Yeah, that’s amazing. It’s like, man, I’m trying to say something. And I feel like what you’re learning in academia is like, how can I bring this back to my community? And help them understand that they’re not crazy and that their communities are being policed, because of so and so reason. That it’s not just in their heads why they see so many cops here, but then they don’t see them when they go to, like Glendale. Trying to make it sound academic, so people in academia listen to you and they care about your lived experiences and then taking it back to your community. It’s like, okay . . . you’re right. What you’re feeling is true. What you’re feeling is valid.

The exchange between Padilla and Rivera-Murillo reveals the significance of research and knowledge production in struggles for social justice. Our work in the CRL allowed them to draw from their lived experiences to engage the transcripts of Latinx lifers and understand how racialized criminalization takes place. They felt their experiences validated in the research and now they feel empowered to have conversations about these issues to bring about change.

Recently, one of these conversations took place. Padilla, Tapia, and Rivera-Murillo presented this research at the 2018 National Association for Chicana and Chicano Studies in a panel facilitated by Escobar. There was a retired Latina high school teacher from Sacramento in the panel and at the end of the presentation she stated, “I can only imagine how difficult this work has been for you. It's painful hearing the stories, I can't imagine having to read through all of them. . . . I came with a different understanding, but I'm leaving an abolitionist.” After the panel, we debriefed and the students stated how meaningful it was to hear someone acknowledge how painful this work is without having to say it; without having to describe how hard it is, how much crying takes place, and how many times they have wanted to give up. However, the fact that they were able to impact another person’s perspective on prisons made all of the difficulties they endured conducting the research worthwhile.

Finally, because of their work with the CRL, students have joined abolitionist efforts to create social change. For example, Rivera-Murillo involved herself in the creation of the Revolutionary Scholars Project, a resource center at CSUN dedicated to supporting formerly incarcerated students (FIS) and systems-impacted students (SIS) (students impacted by the incarceration of a loved one). Through this work, she does not only provide guidance and support to FIS and SIS, but she also engages broader abolitionist efforts. Most recently, she involved herself in organizing to promote the nationwide prison hunger strike that began on August 22, 2018, to protest, among other things, the killing of seven prisoners in Lee Correctional Institution in South Carolina. This, along with the other examples discussed throughout, highlight the value of pedagogy grounded in an abolitionist vision. Because of their work with the CRL, Padilla, Tapia, and Rivera-Murillo have made significant positive changes in their personal lives, but more importantly, they have become active in the larger abolitionist movement.

Conclusion

The Carcerality Research Lab was conceptualized as a pedagogical tool to advance prison abolition through collaborative research. It was intended to be a space of knowledge production for the purpose of positive transformative change. Grounded in Critical Race Theory and abolition pedagogy, the CRL has had a significant impact on everyone involved, particularly students. Their experiential knowledge is valued and greatly contributed to their ability to readily engage the research on the experiences of Latinx lifers in California prisons. The students’ lived experiences growing up in communities affected by criminalization expedited the learning and training process and contributed to their desire to engage abolitionist efforts through knowledge production. As stated previously, one of the greatest struggles of prison abolition work is creating a common sense understanding that another world is possible; that creating a world without prisons (and other carceral spaces) is necessary to bring about social justice. The CRL serves as an example of how engaging in abolition pedagogy enables people to imagine what appears unimaginable, and to become active in moving us closer to a more just world.

Notes

1 The term “Latinx” is employed rather than Latina/o to account for the fact that many individuals are gender fluid and do not adhere to the strict gender dichotomy of male/female.

2 An individual can request up to 10 transcripts a month and there is a financial charge for any additional documents.

3 In 2012 the CDCR converted VSPW, a women’s prison, to Valley State Prison, a men’s prison classified as a Sensitive Needs Yard that houses vulnerable populations, including sex offenders, trans and openly gay individuals, former police and correctional officers, ex-gang members, and others in need of protective custody. People previously housed at VSPW were transferred mainly to CCWF and California Institution for Women.

4 In 2017, of the 131,260 people incarcerated in a California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation facility, 43,142 (32.9%) were sentenced in Los Angeles County (CDCR Office of Research 2017). The next county with the largest number of people is Riverside, with 9,992 (7.6%) (CDCR Office of Research 2017).

5 There are important connections between CRT and Paulo Freire’s (2000) ideas of empowerment through education, including that one must understand how the world works in order to transform it, that one must name and confront reality critically, and that dialogue and storytelling are important tools in confronting oppression. While aware of these connections, we privilege CRT in the CRL because of its focus on racism and white supremacy, which fundamentally inform the criminal legal system in the United States.

6 Other scholars that make a similar argument include Yosso (2005, 2006) and Treviño, Harris, and Wallace (2008).

Works Cited

Bell, Derrick. 1995. “Who's Afraid of Critical Race Theory?” University of Illinois Law Review 1995: 893–910.

CDCR Office of Research. 2017. “Offender Data Points: Offender Demographics for the 24-month period, Ending June 2017.” Division of Internal Oversight and Research, California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. https://sites.cdcr.ca.gov/research/wp-content/uploads/sites/9/2018/05/Offender-Data-Points-as-of-June-30-2017.pdf.

Crenshaw, Kimberlé, Neil Gotanda, Gary Peller, and Thomas Kendall, eds. 1995. Critical Race Theory: The Key Writings that Formed the Movement. New York: The New Press.

Critical Resistance. 2018a. “CR Structure & Background.” Accessed May 5, 2018. http://criticalresistance.org/about/cr-structure-background/.

. 2018b. “What is the PIC? What is Abolition?” Accessed May 5, 2018. http://criticalresistance.org/about/not-so-common-language/.

CSUN Counts. n.d. “All Undergraduate Students.” Characteristics of All Students. Accessed May 21, 2018. https://www.csun.edu/counts/byor_all_undergraduates_students.php.

Delgado Bernal, Dolores. 2002. “Critical Race Theory, Latino Critical Theory, and Critical Raced-Gendered Epistemologies: Recognizing Students of Color as Holders and Creators of Knowledge.” Qualitative Inquiry 8 (1): 105–126.

Freire, Paulo. 2000. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. 30th anniversary ed. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Harris, Cheryl I. 1993. “Whiteness as Property.” Harvard Law Review 106 (8): 1707–1791.

Lopez, Mark Hugo. 2014. “In 2014, Latinos Will Surpass Whites as Largest Racial/Ethnic Group in California.” Pew Research Center. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2014/01/24/in-2014-latinos-will-surpass-whites-as-largest-racialethnic-group-in-california/.

Rodriguez, Dylan. 2010. “The Disorientation of the Teaching Act: Abolition as Pedagogical Position.” The Radical Teacher 88: 7–19.

Solórzano, Daniel G., and Tara J. Yosso. 2002. “Critical Race Methodology: Counter-Storytelling as an Analytical Framework for Education Research.” Qualitative Inquiry 8 (1): 23–44.

Treviño, A. Javier, Michelle Harris, and Derron Wallace. 2008. “What’s so Critical about Critical Race Theory?” Contemporary Justice Review 11 (1): 7–10.

Yosso, Tara J. 2005. “Whose Culture has Capital? A Critical Race Theory Discussion of Community Cultural Wealth.” Race, Ethnicity and Education 8 (1): 69–91.

. 2006. Critical Race Counterstories along the Chicana/Chicano Educational Pipeline. New York: Routledge.