Abstract

As engaged scholars we, Xabi and Natalia, work cooperatively with diverse community groups and community-based alliances to bring Chicanxs’ and Latinxs’ concerns to the center of attention and to make our research a “political vehicle for meaningfully engag[ing] the world and collectively act[ing] within it . . . in order to name the world and transform it” (De Genova 2005, 25). As scholar activists we promote, in different ways, communities’ interests, health, and safety, and promote justice and the well-being of members of the community. In sum, our research reminds us that the experts on the issues of their community are the members of the community themselves, and thus, we need to identify the knowledge and voices (testimonios) of communities of color—in our case, the hijas de inmigrantes Mexicanos (the daughters of Mexican immigrants) living in an unincorporated rural town—and count them as inside experts when doing anticolonial advocacy scholarship and community interventions.Introduction

Chicanx1 advocacy scholarship, which ties research to community concerns and social justice, is not a new endeavor (de la Torre 2014). As early as November of 1968 at San Francisco State University and January of 1969 at UC Berkeley, the Third World Liberation Front (TWLF)—a multiracial coalition of students supported by community members who mobilized for the creation of ethnic studies programs—insisted on relevant research and education that communities of color could use to address their various needs (Gosse 2005).

The Black Student Union and the Third World Liberation Front led the student-led strike at San Francisco State University, which demanded equal access to public higher education, more senior faculty of color, and a new curriculum that would embrace the history and culture of people of color. They demanded a new infrastructure and the hiring of people of color to run the department. After the five-month student-led strike, the lengthiest campus strike in US history, the College of Ethnic Studies was established at SF State in 1969. The significance is that in ethnic studies new content was not only added, but the purpose of education was fundamentally changed. Ethnic studies made education relevant to the needs of their communities. Education and research were seen as tools for community empowerment. It also set the groundwork for the creation of ethnic studies classes and programs at other universities. In a press release commemorating the 40th anniversary of the 1968 strike, Denize Springer wrote that in the wake of the establishment of the College for Ethnic Studies at SFSU, a report issued by the Education Resource Information Center in 1981 concluded that 8,805 ethnic studies classes were being taught at 439 college campuses across the country (2008).

Activist research in its purest form is therefore a critical part of the original mission of Chicana/o studies (and other ethnic studies), and was in fact practiced by members of the Chicana and Chicano movement (Montejano 2010; Rosales 1996).

For the Chicanx community, knowledge and representation in power structures were central to producing real social change, as described in El Plan de Santa Bárbara. In spring 1969, on the UC Santa Barbara campus, a group of Chicanx activists, community members, and intellectuals met and prepared El Plan de Santa Bárbara. This foundational document generated an educational model for institutions of higher learning—both community colleges and four-year state universities—intended to be more responsive to Chicanxs and to provide a bridge for a new generation of Chicanxs to higher education. El Plan de Santa Bárbara recognized the central role of knowledge, research, and representation in power structures and in producing real social change (Rangel 2007). The plan articulated the most resounding rejection of Mexican American assimilationist ideology to date, and called for the implementation of Chicano studies programs throughout the California university system. A major objective was to create a college curriculum that was relevant and useful in redressing social and economic inequality in Chicana/o communities. The plan of action centered on supporting a unified student movement called El Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán (García 1996; Rangel 2007).

As engaged scholars we, Xabi and Natalia, work cooperatively with diverse community groups and community-based alliances, to bring Chicanxs’ and Latinxs’ concerns to the center of attention and to make our research a “political vehicle for meaningfully engag[ing] the world and collectively act[ing] within it . . . in order to name the world and transform it” (De Genova 2005, 25). As scholar activists we promote, in different ways, communities’ interests, health, and safety, and promote justice and the well-being of members of the community. In sum, our research reminds us that the experts on the issues of their community are the members of the communities themselves, and thus, we need to identify the knowledge and voices (testimonios) of communities of color—in our case, the hijas de inmigrantes Mexicanos (the daughters of Mexican immigrants) living in an unincorporated rural town—and count them as inside experts when doing anticolonial advocacy scholarship and community interventions.

Our orientation to research engages partners, as much as it is possible, collaboratively and equitably during the research process. Most of our research begins at the behest of the community, and its goal is to address a need as well as to eliminate a disparity or inequity. Our research approach also challenges the deficit perspective as during the research process we recognize and value the strengths, knowledge, and expertise that each partner, in this case the youth in Knights Landing, brings to the research process. As described by Valencia and Solórzano (1997), deficit assumptions are based on perceptions that place the blame on inmigrantes and account the deficiencies to the inmigrantes’ skills, knowledge, and/or culture. These assumptions can impact the overall success of the hijas de inmigrantes Mexicanos (Gutíerrez 2006; Pérez Carreón, Drake, and Calabrese Barton 2005).

This article is a case-study of activist scholarship with Las Ramonas, a youth group at Knights Landing composed of hijas de inmigrantes Mexicanos. Before we get into this case study we provide background on how we each gained entry into the community.

Entry to the Community

Natalia Deeb-Sossa:

Natalia Deeb-Sossa:

In 2009, two and a half years after I had arrived in the West Coast for the first time, I received a phone call from a community organizer that changed my life. Juanita Ontiveros, who had known of my work with migrant children and their parents during the summer of 2008 (Deeb-Sossa 2015), invited me that summer to Knights Landing, a community that wanted to challenge the decision of the school district to close the only elementary school in their rural community.

The mothers mobilized against the closure of the school, whose student population was 99% the children of Mexican farmworkers (Deeb-Sossa and Moreno 2016). First, the mothers demanded that the school recognize their children’s scores after the superintendent accused the elementary school children of cheating after they received good scores on the year-end exams. The school planned for the students to retake the test, under the watchful eye of the superintendent. The children’s test scores increased and the superintendent had to accept the test results. Second, when the school district board decided to close the elementary school without consulting or notifying the parents, the mothers began to mobilize. They attended every board meeting and demanded the school remain open for their children, given that test scores were improving every year, that their children felt comfortable in their school with their teachers, and that the school was a vital part of the town. Third, the mothers started to gather information about the educational rights of their children and the possibility of opening a charter school. Fourth, the mothers decided to use fototestimonio (photographs taken by the mothers with accompanying mothers’ testimonies) to raise awareness and inform the wider community about their struggles and lives. The mothers wanted the school district officials, and the county community, to understand how their decisions affected their lives and in particular the lives of their children.

Unfortunately, on February 26, 2009, the trustees voted five to two to close Grafton Elementary and bus the children 16 miles to Woodland. Nearly 80 students from Knight Landing were sent to Plainsfield Elementary in Woodland (Deeb-Sossa and Moreno 2016).

The mothers failed to change the decision of the local school board to keep their children’s elementary school open. However, they agreed that their mobilizing efforts were “worth it” insofar as they: 1. became politicized about the educational rights of their children; 2. better understood the workings of the educational system and local political system in the US; and 3. used their knowledge and empoderamiento comunitario (community empowerment), together with their long-term allies and partners, to create a new community health clinic.

After a year of negotiations and collaborations with various academic and nonprofit entities, the new community health clinic in Knights Landing, named by the community Knights Landing One Health Center, became a reality in 2012. The clinic is run by volunteer physicians and nurses as well as volunteer medical students, graduate students in public health, and undergraduate students. As an activist-community-engaged researcher, I witnessed how the farmworker mothers mobilized, together with medical students and local advocates, to open a clinic in their rural community. As of today, it opens every first and third Sunday of the month. This past January, we celebrated the sixth anniversary of the opening of the first student-run clinic with a rural focus and a one-health model. The one-health model is an approach to health work that understands that the well-being of people, animals, and the environment are interdependent locally, nationally, and globally, and thus need to be addressed through collaborative problem-solving. According to the UC Davis website, “All life forms are connected. Understanding the interactions between them is critical to protecting the health of all. One Health is an approach that impacts the quality of our everyday lives” (2018).

Xabi Martinez:

In the summer of 2016, I (Xabi) became the newest member of the Empower Yolo staff working at the Family Resource Center at Knights Landing when I was added on as a Youth and Parent Engagement Specialist through ASSETs (After School Safety and Enrichment for Teens). As a Youth and Parent Engagement Specialist I provide resources and programming during non-school hours to youth who come to the Family Resource Center.

This position didn’t exist before. The Youth and Parent Engagement Specialist for the Woodland High School ASSETs site, Angelica Flores, would have programs for Knights Landing youth when possible. To account for the demand of youth programming in Knights Landing, ASSETs formed a position specific for Knights Landing high schoolers who were in the Woodland Joint Unified School District.

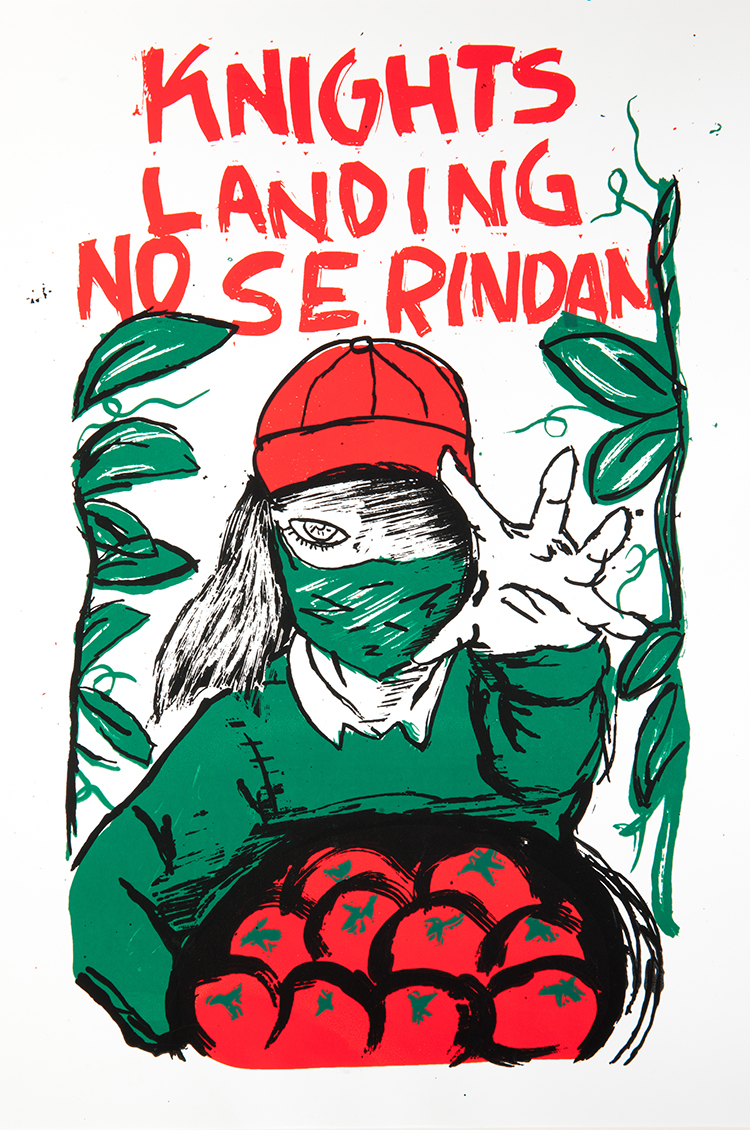

Prior to joining the community through ASSETs, I had met some of the youth at Taller Arte del Nuevo Amanecer (TANA) in Woodland, CA. TANA’s mission is to cultivate the cultural and artistic life of the community, viewing the arts as essential to a community's development and well-being (Taller Arte del Nuevo Amanecer (TANA)). I met some of the youth from Knights Landing through a program that brought youth on probation to the studio to learn how to silkscreen and be introduced to Chicanx culture and activism.

Most of the youth that use ASSETs resources are part of Las Ramonas, a high school girls' group that formed to advocate for themselves and the rest of the community. I transitioned into the Knights Landing community as Las Ramonas were completing their fototestimonio (i.e., narratives, photographs, and narrative-in-photos) project under the leadership of Angelica Flores, and was getting ready to disseminate their images. As of late, the main focus, along with the youth, other organizations, and educators, has been to create sustainable summer programming for the youth of Knights Landing that cultivates self-respect and self-confidence.

Knights Landing: Marginalized and Excluded at Multiple Levels

The mostly undocumented, Spanish-speaking, poor, and rural farmworker families in Knights Landing are marginalized and excluded at multiple levels. Their minority status in terms of class, language, geography, jurisdiction, and labor render them invisible. The community of approximately 1,500 works in temporary or seasonal jobs in agriculture or related industries, including food processing. The unincorporated area of Knights Landing is located in Northern California’s agricultural heartland. It relies economically on several industrial canneries and casinos located nearby. Knights Landing residents, in large part, live in this unincorporated area because of its proximity to work, its affordability, and the possibility of home ownership. However, living on the municipal fringe comes with costs: no flood control, health dangers from local soil, and dependence on rural-character services (e.g., a student-run community/rural clinic). In addition, many residents rely on failing septic tanks and well water that is becoming increasingly polluted. Finally, Knights Landing has no police station, and county sheriffs have struggled to cope with increasing levels of rural crime and gang activity resulting, in large part, from the closure of the teen center, the public park, and of organizations that provided after-school programs to youth in the mid-2000s.

Because Knights Landing residents must rely on the county for services, when they are cut or closed, Knights Landing residents must try to change the county’s mind. As a result, the county “act[s] as [a] gatekeeper . . . [that] hold[s] regulatory powers that shape the material conditions of neighborhood life; . . . advocate[s] to bring private and intergovernmental resources; . . . and . . . serve[s] as [a] forum for participatory democracy” (Anderson 2008, 1134).

Farmworker Youth Mobilization: Las Ramonas

Knights Landing is a rural community that since the 2000s has steadily lost resources vital to its well-being. The first loss was the migrant clinic. Then, the public park and the teen center were closed. Afterward, the community clinic that operated from the local Family Resource Center permanently stopped offering services in 2008 because the small volume of patients was not enough to financially sustain the clinic. This meant that in order to see a doctor and purchase medications, many community members, mostly housewives with young children and the elderly, would need to travel 20 minutes by public bus to the city of Woodland. The limited bus hours to Woodland, which is also the closest source of affordable fresh fruits and vegetables, compounded the obstacles to healthy living. For the farmworkers that did seek medical care, the situation was an almost complete deterrent to accessing medical care, as they worked during the time that clinics in Woodland operated.

In reaction to this looming poverty and deteriorating social capital, a group of predominantly monolingual, English-speaking youth surfaced as leaders. As they came together, the daughters of Mexican immigrants, Las Ramonas, born in the US, learned the local and national “codes of power”—rules established for participation in power (Delpit 1995)—engaged in empowerment, and challenged their town’s marginalization (Carrillo 2006, 181–196).

Community-Based Participatory Research

In April 2016, in the several meetings we had with Las Ramonas, they expressed the desire to bring awareness to the deteriorating social capital2 and poverty in their community. We initiated a community-based participatory research (CBPR) project, recognizing the importance of involving the youth, as much as possible, as participants in the research so that the project could be a means of facilitating social change (Israel et al. 2001; Israel et al. 2008; Minkler and Wallerstein 2008). In light of previous research on the benefits of CBPR (Breda 1997; Stevens and Hall 1998; Webb 1990; Israel et al. 2001; Israel et al. 2008), we hoped that the use of this method would empower hijas de inmigrantes Mexicanos by considering them agents who could investigate their own situations, and provide resources to the youth (photography classes, cameras).

Fototestimonio

Fototestimonio (meaning “photovoice”) is a grassroots approach to photography and social action that is frequently used in CBPR studies. It provides cameras to community members so they can record images that reflect their strengths and problems. Through group discussions of the photographs, fototestimonio promotes dialogue about issues that are important to community members (Wang 1999; Wang and Burris 1994; Wang and Burris 1997; Wang and Redwood-Jones 2001). Photovoice has been defined as

a process by which people can identify, represent, and enhance their community through a specific photographic technique. It entrusts cameras to the hands of people to enable them to act as recorders, and potential catalysts for social action and change, in their own communities. It uses the immediacy of the visual image and accompanying stories to furnish evidence and to promote an effective, participatory means of sharing expertise to create healthful public policy. (Wang and Burris 1994)

Photovoice was developed by Caroline Wang and Mary Ann Burris and is grounded in the work of Brazilian educator Paulo Freire (1970). Freire utilized photos and drawings to promote critical thought about concerns affecting an individual’s community. Wang and Burris (1994) further developed this concept by allowing community members themselves the opportunity to take photos of their own environment. This was expected to produce more insightful images, leading in turn to more meaningful dialogue and to more substantial impact on the community and, ultimately, on policymakers.

In a review of the literature on the use of fototestimonio in health, public health, and related disciplines, Catalini and Minkler (2010) find that the method contributes to an enhanced understanding of community assets and needs. Fototestimonio has proven especially beneficial when used with members of marginalized communities. Castleden and Garvin note the “method’s success at balancing power, creating a sense of ownership in the research, fostering trust, building capacity, and implementing a culturally appropriate research project in the community” (2008, 1398). Participants gain a sense of autonomy and empowerment when they are able to decide what issues concern them. One participant, a member of an underrepresented community, gave the following response when asked if fototestimonio was an effective method to explore his community’s health concerns: “Mhm, for sure, mhm. Because [the photograph] is right there. You can’t lie” (1400).

Context and Sample

Las Ramonas is one of two youth groups that formed around 2013 in Knights Landing, the other being Pueblo Unido. Las Ramonas consists of mostly high school girls that live in and around Knights Landing. They chose the name after identifying with Comandanta Ramona, the late Zapatista of Chiapas.3 Their intentions have included unlearning stereotypes they learn in their communities, self-actualization of their own identities, learning and promoting respect and love, as well as using critical thinking while learning about the world around them in a safe space that is the Family Resource Center in Knights Landing.

In the spring of 2016, the previous Youth and Parent Engagement Specialist of ASSETs, Angelica Flores, agreed to partner with Natalia to engage Las Ramonas in a fototestimonio project. Las Ramonas were inspired by previous fototestimonio projects done in their community. As mentioned above, Natalia led a fototestimonio during the closing of the local elementary school and during the time El Grupo de Mujeres advocated for the reopening of the student-led free clinic (Deeb-Sossa 2015; Deeb-Sossa and Moreno 2016).

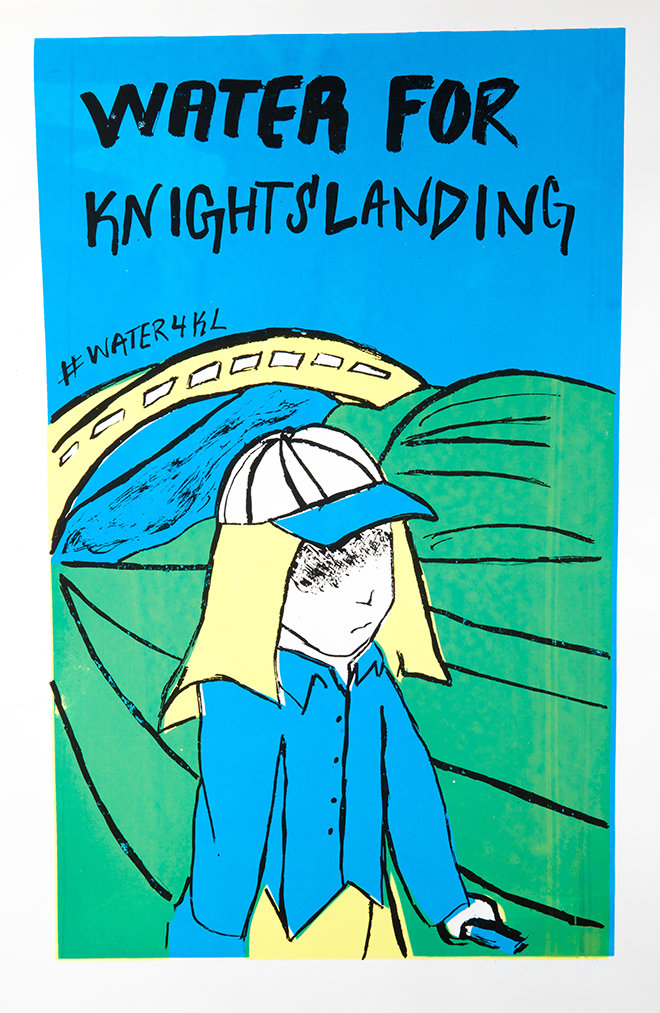

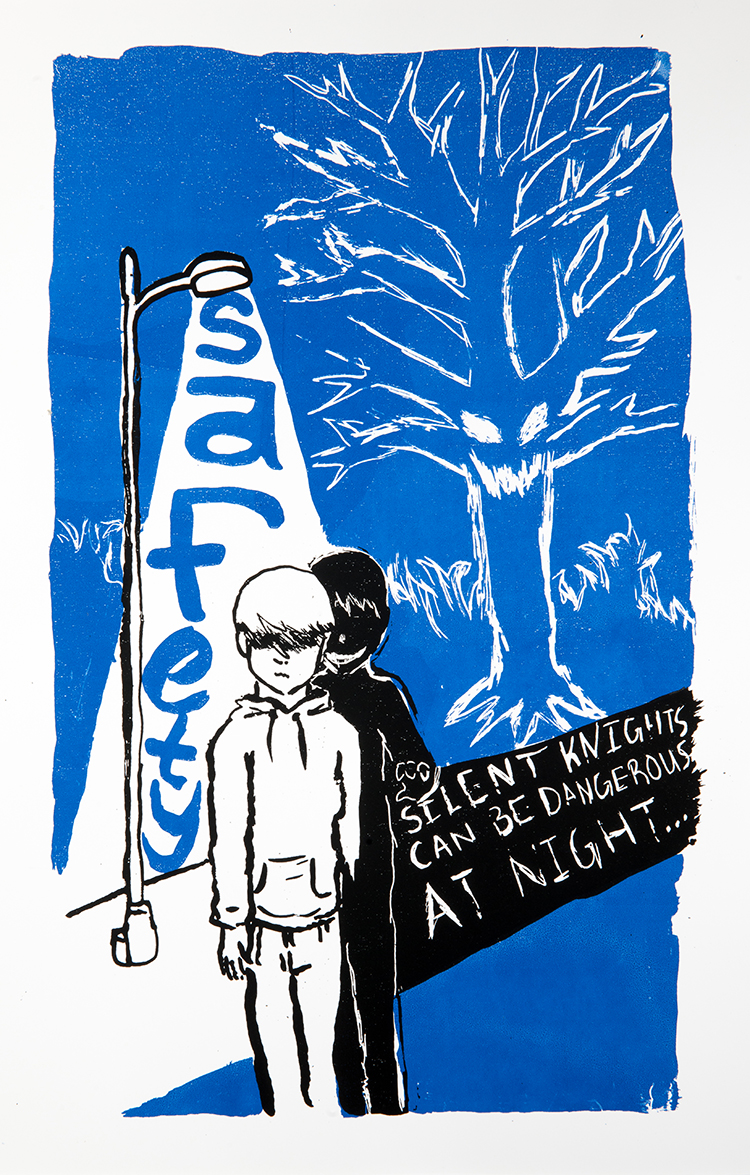

Las Ramonas’ theme was a continuation from a series of prints they were able to complete at TANA right before being introduced to fototestimonio. The three posters discussed safety in terms of lack of lighting in Knights Landing, water quality, and their farmworker parents.

Most pertinent to Las Ramonas in completing their fototestimonio project was the issue of safety and resources in Knights Landing. The images showcased the neglected park in the center of the small town that had unplayable soccer fields and unusable bathrooms; the graffiti being made by youth needing an outlet; and the general safety concern of a busy main road with little to no safety precautions for the community. All the images are shown below.

Figure 5: Las Ramonas’ Fototestimonio project. Courtesy of Las Ramonas.

Results

After a month of taking photos, the youth got together with Xabi and Natalia and decided that at least one photograph from each youth should be included in the final set. However, since the exhibit was about the Knights Landing community they did not want their names to appear with their photos. Instead, “taken by Las Ramonas member” was voted as a way to show unity and that they spoke as one voice for the community. After selecting some 30 photographs, the youth wrote the testimonios (captions) that would accompany the chosen photos.

In Telling to Live: Latina Feminist Testimonios, some Chicana and Latina feminist scholars have defined testimonios as “a form of expression that comes out of intense repression or struggle . . . an effort by the disenfranchised to assert themselves as political subjects through others, often outsiders, and in the process to emphasize particular aspects of their collective identity” (Latina Feminist Group 2001). We were inspired by the visual impact of the Rich and Poor (1985) series by the documentary photographer Jim Goldberg. He made black and white documentary-style photographs of people in their homes, of all socioeconomic statuses, and asked them to write a commentary underneath their portrait. These commentaries reveal the subjects’ struggles with power, class, and happiness. For examples of Goldberg’s work, go to https://www.sfmoma.org/artwork/80.91.

The youth spent a week creating a list of people to invite to the exhibit scheduled at the Family Resource Center as well as at UC Davis. They invited local policy makers, their family members, and the greater community at large in hopes that the exhibit would raise awareness about the struggles they faced.

With a keen understanding of the reach of social media, in particular Facebook and YouTube, Las Ramonas collaborated with Sabrina Sanchez, a multimedia journalist with dual degrees in communication and Chicana/o studies from UC Davis. Las Ramonas decided that the best way to raise awareness about the inequities they were experiencing was to share, via a video, “their truth,” and how they advocated for themselves and their community.

As a Stockton and East Bay Area native, Sabrina’s interest and engagement with Knights Landing was rooted in an effort to provide a service that helped this community take back its power, one story at a time. Sabrina told us that “both reporting and direct community engagement are foundational in her journalistic method.” As a result, Sabrina sought to amplify community voices, providing a critical platform for marginalized communities.

This is the documentary that was produced:

Figure 6: The Youth of Knights Landing Fight for Their Community. Courtesy of Sabrina Sanchez.

The video documents Las Ramonas leading the way as advocates for their families, friends, and neighbors given the vast needs and issues the community is facing. Sabrina told us in a personal message that the video

is a platform for students seeking further questions about how to bridge the resources lost in their community that is predominantly composed of Latina/o farmworking families. . . . I was also fortunate to work extensively with Las Ramonas and highlight their work, in hopes it provides awareness and lends to conversations surrounding the issues plaguing the community.

Discussion

Looking back at the fototestimonio project, Las Ramonas felt that the photos did help surface needs of the community. Although hesitant at first, the members found the public speaking that they were encouraged to do with the photo exhibitions to be exciting and fun. The invitation list to the exhibitions included local policy makers and change makers in the community. One of the exhibitions for the photos was in the Chicana/Chicano Studies department at UC Davis. For most of Las Ramonas, it was their first time on the campus, although they live only 20 miles north of Davis.

Youth did not act as “victims” of inequality, but rather they made use of their fototestimonio as a form of agency to contend with the inequalities they faced in school and in society at large. The hijas de inmigrantes Mexicanos recognized they had some strengths and skills, and in this process, they sought out researchers as allies to help them facilitate discussions about social justice in their community.

Chicana/Latina researchers practicing community-based participatory research must show a long-term commitment to the education and empowerment of marginalized communities. Our community-engaged participatory research has granted us the opportunity to ask hijas de inmigrantes Mexicanos about the concerns they have that are often overlooked, underconceptualized, or ignored by policy makers, politicians, and other researchers. This is a call for repositioning the university to belong to the most marginalized and underserved communities, instead of being aloof and separate from them.

The outcomes of Las Ramonas’ efforts and community organizing discussed above were mixed. The Ramonas failed to get the soccer field fixed, the water issue resolved, or the transportation problems settled. However, Las Ramonas’ efforts did encourage the county to look into the lack of lighting at Knights Landing and, in large part, they are responsible for the current planning of a community garden by the Knights Landing Environmental Health Assessment Project.4

Despite the mixed results, Las Ramonas agree that their mobilizing efforts are “worth it” as they became politicized, saw firsthand how their efforts were directly tied to their opportunities by advocating for a community garden and lighting, and were using their knowledge and empoderamiento comunitario (community empowerment), together with their long-term allies and partners, to seek better opportunities for themselves and their families.

Notes

1 We use, in attempts towards inclusivity and considering intersecting areas of privilege and oppression, the identifiers Chicanx and Latinx (pronounced Chican-ex and Latin-ex, respectively), as a way to move beyond the masculine-centric “Chicano” and the gender inclusive but binary embedded Latina/o or Latin@. Although the official name of the department is Chicana and Chicano Studies, in this article Natalia uses Chicana/o to highlight and center the feminist and radical history of the department and her activist-scholarly work and Xabi uses Chicanx Studies as a way to disrupt the gender binary and claim belonging in the department.

2 Yosso defines in her book, Critical Race Counterstories along the Chicana/Chicano Educational Pipeline, social capital as “the networks of people and community resources” (2006, 45). It is one of the greater array of skills, cultural knowledge, and resources possessed by people of color.

3 La Comandanta Ramona was one of the leaders of the Zapatista National Liberation Army or EZLN, a Revolutionary Committee of Tzotzil and Tzeltal Mayan Indians that initiated a rebellion in the southern Mexican state of Chiapas in January 1994. Subcomandante Marcos was the public face of the EZLN, as he spoke fluent Spanish, and the Tzotzil and Tzeltal Mayan Indians only spoke their native tongues. La Comandanta Ramona was the one who led the rebels into the town of San Cristóbal de las Casas on New Year's Day 1994, demanding greater rights for the indigenous people of Chiapas and protesting Mexico's involvement in the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) which came into force that day. In October 1996, though sick and frail with kidney disease, she defied a government ban and showed up in Mexico City for a National Indigenous Congress. She addressed a crowd of 100,000 supporters in Mexico City's massive central plaza, yelling: "Basta!" ("Enough!"). Comandanta Ramona decried that there was still no hospital in the town of San Andrés de Larrainzer, the nearest to her home village, forcing indigenous people to walk for up to 12 hours for treatment. On January 2006, as she was on the road from San Andrés de Larrainzer to the bigger town of San Cristóbal, her kidney finally failed.

4 The Knights Landing Environmental Health Assessment Project is a collaborative between faculty (Deeb-Sossa in Chicana/o Studies), graduate students from the Pharmacology and Toxicology Graduate Group (Skye Kelty) and Medical Geography (Alfonso Aranda), and community partners. We employ part-time promotoras, community health advocates from the community, as members of our research team to help us with planning, execution of research, and dissemination of results. At the behest of the community, we conducted a community Environmental Health Survey of 100 participants in order to identify the prevalence of environmental risk factors for cancer. We conducted focus groups with about 50 participants to contextualize the survey results and to document the community’s perception of environmental health. We completed a photovoice project so that residents could visually document their environmental concerns. To help address the community’s lack of healthy food options and public spaces, a landscape architect undergraduate, community leaders, and our team are building a community garden. We are now conducting a preliminary environmental sampling to quantify heavy metals and pesticides in household dust and drinking water from private wells. To address the community’s concerns about mental health, we are conducting a mental health and substance abuse survey, and in the summer, we will document mental health needs in this community through focus groups and photovoice projects.

Work Cited

Anderson, Michelle Wilde. 2008. “Cities Inside Out: Race, Poverty, and Exclusion at the Urban Fringe.” UCLA Law Review 55: 1095–1160.

Breda, Karen Lucas. 1997. “Professional Nurses in Unions: Working Together Pays Off.” Journal of Professional Nursing 13 (2): 99–109.

Carrillo, Rosario. 2006. “Humor Casero Mujerista—Womanist Humor of the Home: Laughing All the Way to Greater Cultural Understandings and Social Relations.” In Chicana/Latina Education in Everyday Life: Feminista Perspectives on Pedagogy and Epistemology, edited by Dolores Delgado Bernal, C. Alejandra Elenes, Francisca E. Godinez, and Sofia Villenas. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Castleden, Heather, and Theresa Garvin. 2008. “Modifying Photovoice for Community-Based Participatory Indigenous Research.” Social Science and Medicine 66 (6): 1393–1405.

Catalani, Caricia, and Meredith Minkler. 2010. “Photovoice: A Review of the Literature in Health and Public Health.” Health Education and Behavior 37 (3): 424–451.

Deeb-Sossa, Natalia. 2015. “A tráves de mis ojos: Fototestimonios with Children Growing Up in Immigrant and Migrant Communities in Northern California.” In Documenting Gendered Violence: Representations, Collaborations, and Movements, edited by Lisa M. Cuklanz and Heather McIntosh. New York: Bloomsbury.

Deeb-Sossa, Natalia, and Melissa Moreno. 2016. “¡No cierren nuestra escuela!: Farm Worker Mothers as Cultural Citizens in an Educational Community Mobilization Effort.” Journal of Latinos and Education 15 (1): 39–57.

De Genova, Nicholas. 2005. Working the Boundaries: Race, Space, and Illegality in Mexican Chicago. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

de la Torre, Adela. 2014. "Benevolent Paradox: Integrating Community-Based Empowerment and Transdisciplinary Research Approaches into Traditional Frameworks to Increase Funding and Long-Term Sustainability of Chicano-Community Research Programs." Journal of Hispanic Higher Education 13 (2): 116–134.

Delpit, Lisa. 1995. Other People’s Children: Cultural Conflict in the Classroom. New York: The New Press.

Freire, Paulo. 1970. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Continuum.

García, Ignacio. 1996. “Juncture in the Road: Chicano Studies Since El Plan de Santa Barbara.” In Chicanas/Chicanos at the Crossroads: Social, Economic, and Political Change, edited by David R. Maciel and Isidra D. Ortiz, 181–203. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press.

Goldberg, Jim. 1985. Rich and Poor: Photographs. New York: Random House.

Gosse, Van. 2005. "Third World Liberation Front: The Politics of the Strike, 1968." In The Movements of the New Left, 1950–1975, 127–128. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Gutiérrez, Kris D. 2006. Culture Matters: Rethinking Educational Equity. New York: Carnegie Foundation.

Israel, Barbara A., Amy J. Schulz, Edith A. Parker, and Adam B. Becker. 2001. “Community-Based Participatory Research: Policy Recommendations for Promoting a Partnership Approach in Health Research.” Education for Health 14 (2): 182–197.

Israel, Barbara A., Amy J. Schulz, Edith A. Parker, Adam B. Becker, Alex J. Allen III, and J. Ricardo Guzman. 2008. “Critical Issues in Developing and Following CBPR Principles.” In Community-Based Participatory Research for Health, edited by Meredith Minkler and Nina Wallerstein, 47– 66. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Latina Feminist Group. 2001. Telling to Live: Latina Feminist Testimonios. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Minkler, Meredith, and Nina Wallerstein. 2008. “Introduction to CBPR.” In Community-Based Participatory Research for Health, edited by Meredith Minkler and Nina Wallerstein, 5–24. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Montejano, David. 2010. Quixote's Soldiers: A Local History of the Chicano Movement, 1966–1981. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Pérez Carreón, G., Corey Drake, and Angela Calabrese Barton. 2005. “The Importance of Presence: Immigrant Parents’ School Engagement Experiences." American Educational Research Journal 42 (3): 465–498.

Rangel, Javier. 2007. "The Educational Legacy of El Plan de Santa Barbara: An Interview with Reynaldo Macías.” Journal of Latinos and Education 6 (2): 191–199.

Rosales, F. Arturo. 1996. Chicano!: The History of the Mexican American Civil Rights Movement. Houston: Arte Público Press.

Springer, Denize. 2008. “Campus Commemorates 1968 Student-Led Strike.” SF State News, September 22. http://www.sfsu.edu/news/2008/fall/8.html.

Stevens, Patricia E., and Joanne M. Hall. 1998. “Participatory Action Research for Sustaining Individual and Community Change: A Model of HIV Prevention Education.” AIDS Education and Prevention 10 (5): 387–402.

UC Davis. 2018. “What Is One Health?” Accessed February 6, 2018. https://www.ucdavis.edu/one-health/what-is-one-health/.

Valencia, Richard R., and Daniel G. Solórzano. 1997. “Contemporary Deficit Thinking.” In The Evolution of Deficit Thinking: Educational Thought and Practice, edited by Richard R. Valencia, 160–210. New York: RoutlegeFalmer.

Wang, Caroline, and Mary Ann Burris. 1994. “Empowerment through Photo Novella: Portraits of Participation.” Health Education Quarterly 21 (2): 171–186.

Wang, Caroline C.1997. “Photovoice: Concept, Methodology, and Use for Participatory Needs Assessment.” Health Education and Behavior 24 (3): 369–387.

. 1999. “Photovoice: A Participatory Action Research Strategy Applied to Women’s Health.” Journal of Women’s Health 8 (2): 185–192.

Wang, Caroline C., and Yanique A. Redwood-Jones. 2001. “Photovoice Ethics: Perspectives from Flint Photovoice.” Health Education and Behavior 28 (5): 560–572.

Webb, Christine. 1990. “Partners in Research.” Nursing Times 86 (32): 40–41, 43.

Yosso, Tara J. 2006. Critical Race Counterstories along the Chicana/Chicano Educational Pipeline. New York: Routledge.