Abstract

This article presents the formation and methodology of Taller Arte del Nuevo Amanecer (TANA). TANA is a community-based art program of the Chicanx Studies Department at UC Davis and located off campus within a subsidized housing community in Woodland, California. The formation of TANA, the methods employed within its space, and the challenges to situate the program within an Ethnic Studies department highlight central issues within the debate over how socially engaged scholarship is enacted within land-grant research universities.TANA: Challenging Enclosure

Public and socially engaged scholarship are current keywords that are being enclosed in Universities. Public and socially engaged scholarship are resignifications of oppositional practices that have been excluded from and challenged by communities that have been historically marginalized and underrepresented. That is, public and socially engaged scholarship are extensions of methods that are not legible in the current structure of the research university that expects knowledge to be formed through the twin processes of externally funded research or peer-reviewed publications from commercial and university presses. At the core, the questions and tensions over what constitutes public and socially engaged scholarship and how they are valued in the public research university is ultimately about contending with the communities that have challenged hegemonic knowledge production and their demands for the resources of the institution to be reoriented towards interventions that support social justice and equity. How can oppositional community-based practices be centered in the rubric of the public research university’s merit and promotion process? If these practices are expressed in the university and challenge it to redistribute resources, what needs to occur to ensure that the practices are not tokenized and enclosed around meaning that limits their potential for transformation? How does one engage in generationally sustained community-based practices without major revenue streams from external grants or corporate donations? How does one contend with the ideology implicit in the university’s merit and promotion processes while engaging in community-based practices that yield no legible research? How exhaustively does one attempt to reconcile the contradictions implicit within these questions?

In this article, I present Taller Arte del Nuevo Amanecer (TANA), a community-based art center run by the Chicanx Studies Department at UC Davis, which is at the nexus of the debate over the role of socially engaged scholarship in the public university. The mission of TANA is to facilitate community transformation, social justice, and equity by utilizing visual culture as a means to stimulate dialogue and representation. TANA seeks to accomplish this by creating a tangible connection between the undergraduate community-based studio art curriculum taught in the Chicanx Studies Department at UC Davis and a broader community that has limited access to the university’s resources. Screen printing within a praxis-oriented community workshop is a core method employed within Chicanx Studies that has been a part of the curriculum since the founding of Ethnic Studies in 1969. These methods have been marginalized as illegible forms of research in the university’s matrix, despite being an expression of the core mission of the land-grant institution to tangibly serve community with new research and curriculum. TANA reveals a tension in the logic of the institution because it serves a community constituency that historically has not had the economic resources to demand the attention of the university through sustained engagement. In thinking of TANA in relationship to the broader debate over what constitutes research in socially engaged practices, I question how oppositional practices that have emerged within Ethnic Studies can remain relevant to the community without enclosing their liberatory potential in efforts to gain legibility. The focus of this contribution to Public’s special issue on “Public Scholarship, Place, and Proximity” is to delineate how TANA was established as a program of the Chicanx Studies Department and located in a subsidized housing community, as well as to speak to the tensions that exist to the program’s formation and sustainability. Here, I argue that the methods TANA employs and outcomes it generates are rigorous and impactful forms of knowledge production that are centered within Chicanx Studies and evidence of five decades of socially engaged research that centers community engagement.

The Formation of TANA

I cofounded TANA with Malaquias Montoya, Professor Emeritus of Chicanx Studies. We are currently preparing the 10-year anniversary for our program. While TANA has been operational as a site for almost a decade, it has been in formation since 1969 with the emergence of Chicano Studies and Ethnic Studies out of the Third World Liberation Front Strike in the San Francisco Bay Area. Today, TANA is located 12 miles north of UC Davis in Woodland, California, in a subsidized housing community where over 900 residents live below the federal poverty line. TANA leases a 3,600-square-foot refurbished warehouse that is owned by the Yolo County Housing Authority (now named Yolo County Housing). TANA is explicitly a program of the Chicanx Studies Department and leases this site through the umbrella of UC Davis. Malaquias and I received the key to the TANA building at 1224 Lemen Avenue in Woodland on September 1, 2009, and I began leading programming within the space in January of 2010.

Woodland, California, was identified as the city where we would initially establish TANA because it represented the racial and economic disparities that necessitate critical community-based engagement. Woodland is the Yolo County seat, which houses UC Davis. By comparison to Davis, a small college town with expensive and inaccessible real estate, Woodland is a working-class and diverse community where many of the agricultural and service workers live who support the local farming, manufacturing, and logistics economies. In Woodland, there is a significant Chicanx/Latinx community of mixed economic and educational backgrounds and a far lower college-going rate for students educated in the public school system. In 2003, when Malaquias and I began the effort to organize a community-based advisory group to support TANA’s founding, there was a significant cohort of alumni of the Chicano Studies Department living in Woodland who hoped to facilitate deeper engagement from the university within underrepresented communities. By 2003, the Chicanx Studies Department was 34 years old, with several generations of graduates who had been working to manifest community-based, social-justice-oriented methods in their respective professional environments. This unique cohort of Woodland residents created a critical voice to support the formation of TANA at its current site.

Between 2003–2007, Malaquias and I had many discussions to outline a program for a community-based art center. This discussion developed on three fronts. First, we created a programmatic outline based on the curriculum from the community-based studio art curriculum of the Chicanx Poster Workshop and Chicanx Mural Workshop, which are taught within the Chicanx Studies Department. Second, we developed a community-based advisory group of local educators, activists, and representatives to provide broad community representation for our engagement. Third, we sought community partners to support the development of a site for our program. This outline and community advisory group were created in conjunction with a parallel discussion with existing Chicanx Studies faculty to prioritize and secure departmental support for creating TANA as a critical program of the department. This entire effort was unfunded. Malaquias and I had no funding to support our site, program, or staff. We simply had an idea that was supported by local community members and the faculty of Chicanx Studies at UC Davis.

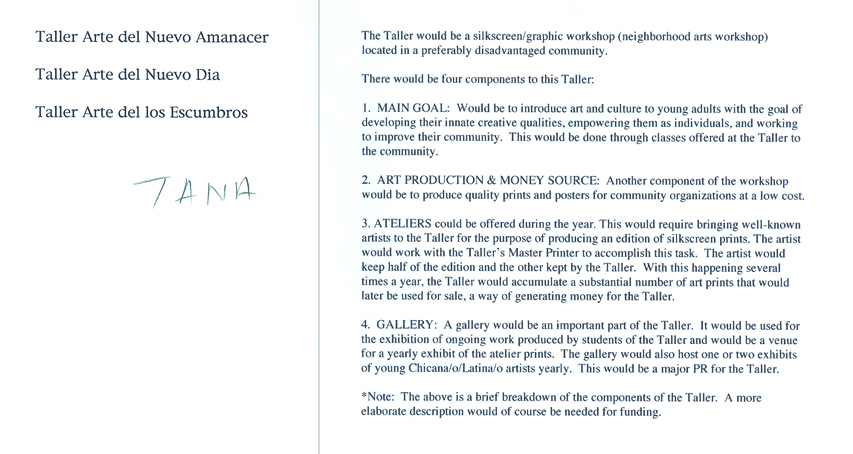

The aspirational vision that Malaquias and I developed for TANA in 2003 identified four main components of the program. This vision coalesced into a program narrative and mission statement that was circulated amongst our community allies and partners. TANA would have a screen-printing studio where weekly poster/print workshops would be held open and free to local community members. TANA would have a gallery/exhibition space to feature artwork produced in TANA workshops and by local/regional/national artists who engage oppositional artistic practices within community. TANA would facilitate a visiting artist print program, where visiting artists would come and work with a master printer to produce limited-edition portfolios. The visiting artist program was to provide the community residents and participants opportunities for dialogue with practicing artists. Last, TANA would provide design and visual art services to local community-serving organizations. The main goal of these four components was to “introduce art and culture to young adults with the goal of developing their innate creative qualities, empowering them as individuals, and working to improve their community” (see Fig. 6). This mission was rooted in the Chicanx Studies mission to overturn deficit-thinking discourses of historically marginalized communities by facilitating representation through praxis.

Between 2003 and 2006, we worked with the community advisory group to expose the broader Woodland community to our programmatic ideas and aspirations. The community advisory group facilitated a partnership with the Yolo County Housing Authority (now called Yolo County Housing, referred to here as YCH) to house TANA at a soon-to-be deserted maintenance warehouse in its subsidized housing community called Donnelly Circle/Yolano Homes. This building was a 3,600-square-foot space adjacent to YCH’s administrative headquarters, servicing the residences that the organization managed. In 2005, YCH was building a new administrative and maintenance headquarters and vacating this facility. The YCH administration had identified the maintenance warehouse as a potential future site for community-service programs for the local YCH residents. Through discussions between the YCH administration and the TANA Community Advisory Group, a commitment was made to house TANA’s future program in the soon-to-be vacated maintenance facility. YCH would commit to providing the space as-is for a $1/year lease to the Chicanx Studies Department. In turn, the Chicanx Studies Department would secure the resources to deliver programming to the local community.

Once vacated by the YCH maintenance division, the building was an ideal site to build a community screen-printing studio. In 2005, Malaquias, myself, and the TANA Community Advisory Group believed we were situated to begin working in the space immediately. But, since we were building TANA as a program of the Chicanx Studies Department at UC Davis, we had to negotiate the university’s risk management, facilities, and real estate services divisions. In 2005, the process of building TANA slowed down considerably, as the university administration began the process of reviewing our lease. It was determined by the campus administration that we would have to bring our future site at 1224 Lemen Avenue up to California educational code requirements for classroom space. This involved seismic retrofitting, ADA accessible restrooms, an HVAC system, and fire suppression. We were informed by UC Davis’s real estate services and architects/engineers division that we needed to raise an estimated $325,000 to turn the building into a leasable space. Between 2005 and 2009, working with the community advisory group, we applied for Community Development Block grants from the City of Woodland to cover the cost of retrofitting the building.

We were not prepared for the administrative challenges that would come from establishing an off-campus site to run a community-based art program. The university is well-situated to support projects and initiatives that have financial resources, such as those that come from externally funded research or from donors and endowments. We had no large donors nor any externally funded grants to support TANA. During the 2005–2009 timeframe, we applied for many external grants to support the arts programming we had proposed at TANA. In applying to, for instance, the National Endowment for the Arts, we had to submit our application using the traditional campus mechanisms for reviewing contracts and grants. Under this rubric we had to apply for funding as “Regents of the University of California.” Many of the national, statewide, and local arts funding agencies focused on supporting community-based arts organizations. There was a consistent resistance to fund our proposals under the guise of the “Regents of the University of California,” with a multi-billion-dollar budget. Where the “Regents of the University of California” is a powerful entity to support large science-based research or traditional humanities projects, it disadvantaged the community-based efforts we employ within Chicanx Studies. Whereas we were successful in utilizing the community-based support for our program in securing funding to renovate our future site, we were unable to activate that support to generate large sources of income to support the program.

With this human labor, we were able to secure the necessary resources to attain a lease for our current site and on September 1, 2009, we were handed the keys to an empty space that had two restrooms that were ADA code compliant, a small office, a darkroom, and a storage room. When we were planning and organizing TANA’s formation, California and the nation were in a robust economic expansion. We believed if we could open our program and demonstrate success we would be able to advocate for future programmatic resources to sustain our engagement. Yet, when we received the keys to TANA, California and the nation had recently entered the deepest part of the Great Recession. In 2009, the university was running a deep deficit while increasing tuition exponentially. Any commitment for future funding from the university at this time was unlikely, as there were considerable layoffs and reductions of budgets across the campus. It was in this context that we set out to build TANA. We had no permanent budget or staff. I cofounded TANA with Malaquias Montoya, but he retired from the faculty in Chicanx Studies in 2008, a year before we would open TANA. As a result, from its inception I would end up serving as TANA’s primary administrator. With no permanent staff or budget, we built TANA’s program primarily with the support of Chicanx Studies undergraduate students who either volunteered or were paid with a work-study subsidy. For the first two years of TANA’s existence, many of these undergraduate interns rode the local public bus system from UC Davis to Woodland to work at TANA. It was with a volunteer team and undergraduate work-study students that we were able to establish a four-day-a-week program whereby community residents could engage in community-based screen printing for free and a quarterly exhibition schedule within the gallery.

Community-Based Art Practice within Chicanx Studies

TANA was founded as a direct extension of the undergraduate curriculum in Chicanx Studies at UC Davis, which is a nationally unique department. It was an early leader in foregrounding Chicana feminisms at a time when patriarchal ideologies dominated the field. In 1982, faculty in Chicanx Studies led the formation of MALCS (Mujeres Activas en Letras y Cambio Social) to create space for feminist formations of scholarship and subjectivity. Today, MALCS is a national program that has engaged generations of scholars and cultural workers. In 1990, faculty in Chicanx Studies formed the Chicana/Latina Research Center which, for two decades, would provide space to Chicana/Latina scholars who were addressing critical issues in their scholarship. While the Chicana/Latina Research Center no longer exists as a program, MALCS continues to thrive as a national program that facilitates a summer institute and peer-reviewed journal. In this respect, Chicanx Studies at UC Davis had a history of developing spaces to facilitate oppositional methods and research practices for communities that had been historically marginalized within the Chicanx/Latinx community and in academia more broadly. These efforts sought to provide tangible programmatic links between the knowledge produced within the university and broader communities that are underrepresented within its matrix.

By reestablishing the direct link between the academic department of Chicano Studies and a broader community context outside of the university, I am gesturing toward El Plan de Santa Barbara’s manifesto that signifies the “Chicano” in “Chicano Studies” as representing a “root idea” that is to be made in a “common social praxis” to foster community self-determination (Chicano Coordinating Council on Higher Education 1969). Here I am also referencing Rosa Linda Fregoso’s signification of “Chicano” as a “space where subjectivity is produced” and the awareness of the context and conditions that necessitated the Chicano Movement to retreat to “more localized sites of resistance, namely universities and cultural centers. Both foreground 'Chicano' as a space where subjectivity is produced through praxis to manifest social justice and community transformation" (Fregoso 1993). TANA was to be a space that encourages the signification Rosa Linda Fregoso proposed.

TANA is an extension of the community-based studio art curriculum that is taught within the department. In 1989, Malaquias Montoya was hired in Chicanx Studies at UC Davis as a full professor to institute a series of studio art courses. As Alma Lopez notes in “Artists as Migrant Workers: From Community to University Teaching,” this is unique because most Ethnic Studies and Chicanx Studies departments at universities center cultural critique and analysis and almost entirely exclude artists and cultural workers from their faculty ranks (2015). In this regard, art and culture have been rendered legible objects of analysis for scholars but not viable and legitimate academic inquiries in themselves. Chicanx artists who have oppositional visual and performative practices that center community engagement are almost entirely excluded from mainstream art departments. Traditional academic art departments hire and promote faculty primarily on their impact within the art environments of the corporate gallery structure and mainstream museums. Many Chicanx artists who have methodologies grounded in the history of the Chicanx Art Movement seek to manifest their work within a broad community context that is almost entirely excluded from corporate and mainstream art institutions. This exclusion is not simply a matter of instituting greater ethnic/racial diversity and inclusion in the faculty ranks, but rather requires a total shift in what is a viable audience for the reception of oppositional cultural and visual methodologies. As a result, Chicanx artists and methodologies have been overwhelmingly excluded from faculty ranks.

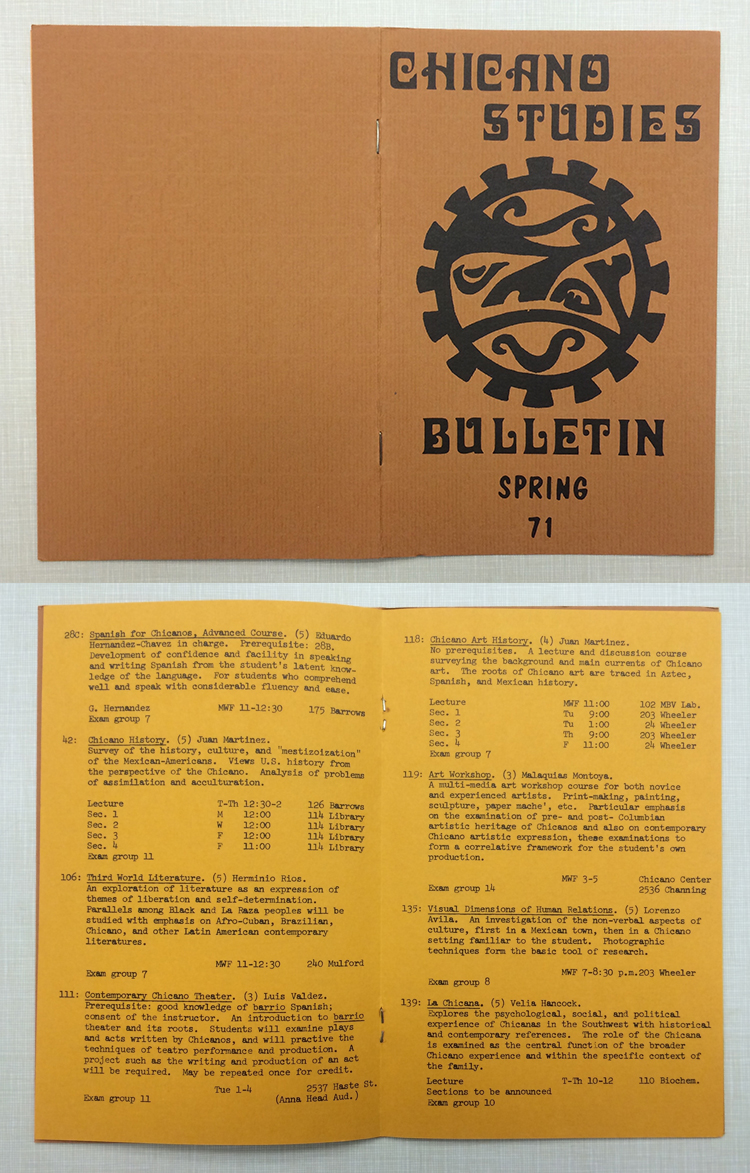

In Chicanx Studies at UC Davis, by contrast, a studio-based curriculum is a central part of the undergraduate experience for students, whereby they can engage in screen printing and muralism as tangible methods to manifest community transformation. Chicanx Studies is one of the few Ethnic Studies departments across the nation that offers art making as a unique oppositional method central to its curriculum. This curriculum was first established in 1969 when the Third World Liberation Front strikes at UC Berkeley and San Francisco State University created a rupture in the university to establish Ethnic Studies. In the fall of 1969, as a result of the TWLF strike, the first Chicano Studies courses were taught at UC Berkeley and community-based art practice was an integral part of this first Chicano Studies curriculum. Studio art courses promoted muralism and poster making as two unique community-based art forms that were central to the formation of the Chicano Movement and subsequently, Chicano Studies.

TANA cofounder Malaquias Montoya implemented this curriculum and taught in Chicano Studies at UC Berkeley from 1969 until 1974. Between 1977 and 1989, Malaquias taught a version of this curriculum at California College of Arts and Crafts in Oakland. In 1989, Malaquias was hired in Chicanx Studies at UC Davis and reestablished this curriculum in the department as a series of screen-printing poster and mural workshops accompanied with an art-historical survey of Chicanx art. The reinstitution of this curriculum within Chicanx Studies should be read as a re-centering of cultural and creative practice as core Chicanx Studies methodologies that seek to facilitate community representation and engagement. Malaquias taught this curriculum from 1989 until his retirement in 2008, at which time I took over leadership for stewarding these courses.

Since this curriculum was established in Chicanx Studies at UC Davis, many students who enrolled in the Poster Workshop and Mural Workshop would become deeply excited about the transformational potential of engaging these methods in a community context. When students would complete the Poster Workshop and Mural Workshop often they would ask Malaquias or myself what they could do to stay involved or to do more advanced-level work. While Chicanx Studies at UC Davis is a stand-alone department that manages its own merit and promotion processes and curricular development, it does not have a graduate program to facilitate these methods at a level beyond the undergraduate experience. Prior to TANA’s founding, there was constant pressure from previous Poster Workshop and Mural Workshop students to engage these methods in more advanced and rigorous levels. It was decades of this pressure and interest that indicated there would be a consistent flow of undergraduate students and alumni who would have interest in working at a community site like TANA, applying the methods of the Poster Workshop and Mural Workshop in a community context.

The Chicanx Studies Department supported this effort by committing a full-time tenure-track faculty member to direct the program. I was hired in 2007 as an Assistant Professor with the charge to build and direct TANA. While I was tasked with this challenge I was also expected to attain tenure through the campus’s standard merit and promotion processes. To support my directorship of TANA I was provided a course release. In essence, from 2009 until 2015 I was administering TANA without any permanent staff, serving as its primary grant writer, curator, workshop coordinator and instructor, and fiscal manager. We built a team with Malaquias Montoya, as emeriti faculty, co-coordinating the workshop. Jaime Montiel, a local painter and printmaker, would be named Artist-in-Residence in 2010, volunteering his time to instruct the workshop. Maceo Montoya, artist and writer, would be hired in Chicanx Studies in 2012, to partly assist in supporting the artistic program of the space. Between 2009 and 2014, Gilda Posada, Roque Montez, Olivia Hernandez, and Chucha Marquez would serve as work study students and key interns in leading instruction in the workshop. I served as Director from 2009–2015. Between 2015 and 2017, Maceo Montoya served as Director. Today, I again direct TANA with an Associate Director and Chief Curator, Jose Arenas, and a Workshop Coordinator, Drucella Miranda.

TANA: Object-Oriented Praxis

The TANA program is primarily centered on engagement through the free, weekly screen-printing workshops. TANA is open Tuesday through Thursday between 12:00–6:30 p.m. and on Saturdays from 11:00 a.m.–4:00 p.m. During this time, community members can, at no cost, attend the workshop. We run these workshops quarterly, coinciding with UC Davis’s quarter schedule of fall, winter, spring, and summer. Each session is approximately nine weeks so as to allow UC Davis undergraduate students the ability to intern at TANA while concurrently enrolled in courses.

The TANA staff and interns recruit for each session, which begins with an introductory screen-printing demonstration where we introduce the workshop to existing and new participants. This introductory demonstration is very brief. Our aim is to excite the new potential participants to the process of screen printing. This provides us a brief space to outline workshop ground rules and to get participation waivers signed for youth under 18 years of age. We publicize and recruit community members to attend the introductory screen-printing demonstration to facilitate a cohort of new and continuing participants at the start of each quarter. Yet many community members flow into TANA throughout the quarter and we welcome any community member to participate whether or not they attended the introductory demonstration. This ongoing educational process is one of the key challenges and opportunities presented by running a free/open community program that requires instruction.

The core work of TANA comes from the engagement between a community participant and Chicanx Studies intern. The interns will have taken the community-based art curriculum within Chicanx Studies before interning at TANA. The primary course that provides training for doing advanced interning at TANA is CHI 172: The Poster Workshop. This course instructs students in the process of identifying a critical community concern, developing imagery to support a campaign, and familiarity in all facets of the screen-printing process. Through this course, students produce three poster projects in editions of 25–40, with the expectation that their posters will be distributed to community organizations to be utilized in social-justice-oriented campaigns. The poster is the tangible outcome of a student’s engagement in the course, but it is not the most critical one.

The most critical outcome of the poster workshop that I seek to foster at TANA is the dialogue that occurs in the studio space. This dialogue occurs at many levels, between intern and community participant, between Chicanx Studies interns, and between community participants themselves. We teach the technical aspects of making a screen print, from idea, to layout, to stencil production, to the printing process. Community members who participate in the workshop become proficient in this technical practice. The technical expertise of screen printing can be generative. The process of screen printing is the activity that mediates dialogue. The poster workshops in Chicanx Studies at UC Davis and at TANA are organized with the basic ground rule that while in the space, participants or students do not shut themselves off with headphones. Rather, everyone in the studio sits together and collectively works on their print projects. Workshop participants also are expected to help one another throughout the process, by dialoguing around visual ideas, by sharing technical approaches to stencil development, and by assisting in the printing process through racking of prints or cleaning of screens.

Community members, ages 12 and older, participate in TANA’s workshops. When they begin, we have two very loosely formed syllabi that guide their engagement. We start by asking participants to create a print based upon a memory of their family or of their community. When asking community members to represent their community, we are encouraging the broadest and most generative representation of community. That is, community not as an enclosure but rather as a space they wish to create and participate within. Prints generally take a couple of weeks of work in the studio to complete. Upon completing two iterations of this assignment, participants are encouraged to make a print about a social issue or concern, either local or global. The questions that are generated by these very loosely formed assignments require dialogue within the workshop to form visual representations. Often, TANA community participants will need to do research, which the TANA interns facilitate. The questions that arise from representations of family, community, and social issues create an object that mediates dialogue, necessitating critical problem solving in order to manifest a completed screen print. This dialogue is part of the ongoing object-oriented praxis that is at the heart of the TANA mission. TANA participants, by creating screen prints, have the platform to visualize how community is imagined, while transforming the structural barriers that obstruct self-determination and social justice. One print at a time, futurity is generated, which is facilitated through critical dialogue.

TANA: A Space Where Subjectivity Is Produced

In this article, I have selected four prints to sample the content and representational strategies of TANA community participants. Family portraits have figured prominently in the first projects community members attempt. In Fig. 20, a youth participant created a print of her father who was a farmworker in the local Yolo County region. The print is made using Rubylith film cut with an X-Acto knife, with subtle layers of light blue and grey. The color choice for this print is unusual as it doesn’t seek to represent the world as it appears traditionally with a logical color structure. Here, the central figure appears as various shades of light to dark blue/grey. Because of this, the figure appears to materialize from the print itself. While the print quality of the knife-cut stencils creates rigidity, the portrait’s affect is subtly humanistic. The darkest stencil is a blue/grey that defines the face and neck. This stencil defines the figure’s gaze, which is tired and hopeful. The figure, who is sitting for this portrait, does so with affection and love. The affect created by this print was intentional through the decision-making process in how the print was developed.

In Fig. 21, a community youth created “Diana Ramirez,” a portrait that is naturalistic layers of light brown for skin, red for lips, and dark outlines to create the three-dimensional structure of the figure. Small cross-hatching creates a texture that facilitates the representation of the figure as three-dimensional. The stencils in this print are developed using ink on acetate, a process that clearly shows the participant’s human hand. Each line and mark is an expression of the participant’s engagement. In this print, Diana Ramirez sits atop a blue background with a pattern of flowers. The use of pattern will also be a unique addition to prints seen throughout many of the community members’ print projects. Sitting atop this pattern, “Diana Ramirez” stares back at the viewer directly, a quality one will find in many of the portraits created at TANA. These figures are confronting the viewer with their agency. On the bottom of the print, in large letters, is the name “Diana Ramirez.” This name is printed in blue with a red outline, the same blue that is the background of the print and the same red of the figure’s lips and the flowers in the background. The name along the bottom of the print is a demonstrative statement: Diana Ramirez is present. This demonstrative statement is similar to the heroic prints one finds in the canon of Chicano art, often reserved for the heroic “great man” figure of history. Here, the great heroic figure construction of history and community is subverted with a TANA participant’s representation of their family member.

When participants advance beyond their first community representational print, they are encouraged to address community issues or concerns, from the local to the global, that they identify as critical issues that need to be addressed in order to encourage equity and social justice. Experiences in the school system are a central topic of discussion between participants and Chicanx Studies interns. The print in Fig. 22 is a participant’s third full project, which addresses the high-school-dropout rate at the local public high school. In this print, we see the entryway and facade of Woodland High School. An assembly line of nondescript figures walks out of the school and one by one drop off a cliff into a sediment that fossilizes. While this print is rife with printing issues (off-registration, uneven printing) it is one of the most successful and meaningful projects I have facilitated. In this print, the color of the sedimentary area that devours the assembly line figures is the same as the high school. The community youth who created this print strategically used the same color for the school and cliff in order to represent the link between the school system and the production of the high-school-dropout rate. I find this print to be deeply affecting and haunting. As a tangible outcome, this print stands as a historical document to this critical issue from the perspective of one seeking to persist within its structure. The intangible outcome of this print project and experience at TANA, and perhaps the most meaningful, is the dialogue that took place between the Chicanx Studies intern and the community participant in the creation of this visual representation.

At the end of each quarterly workshop, TANA opens a new exhibition in its gallery. We typically host four exhibitions a year to coincide with the four quarterly workshops. Of these four exhibitions, two are organized around a theme or feature visiting artists from the region. The remaining two exhibitions are dedicated to featuring the work of the Chicanx Studies interns and curated exhibitions of present and past work from TANA and the Chicanx Studies Poster Workshop. During each exhibition opening, whether central to it or ancillary, we frame the posters generated by TANA community participants. The framing and exhibiting of the TANA participant’s work at the end of each quarter encourages attendance of family and friends to the exhibition opening. This moment provides a space for sharing the work created in the TANA workshops and engaging in a broader dialogue with visitors to the space around the representations and issues raised within each print. In these moments, the youth and participants serve as the facilitators for translating the work at TANA to their family members and friends. A powerful moment can be seen in Fig. 23 at the spring 2012 exhibition opening, where two mothers are accompanied by their children, standing before a wall of framed TANA participant work. At the time of this photo these two mothers, Rosa and Nora, worked in the evenings as janitors at local community health clinics. Despite working evenings, these two joined their children in participating in TANA. Their children (from left to right) Katie, Anyeli, and Vanessa, would create prints alongside their mothers. They would work collaboratively, sharing ideas while encouraging one another’s print production.

One print, of the thousands produced at TANA in its first decade, stands out for how it represents the goals and aspirations of the program. In this print, Fig. 24, Rosa (mother at far left in Fig. 23) has created a simple three-color self-portrait in a subtle gray scale. Rosa stares at the viewer with the agency of representation. Along the back of this portrait, Rosa created a pattern. The pattern is a unique feature of this print, as it came about through dialogue with Chicanx Studies intern Gilda Posada, who had begun creating new patterns in her own print practice as a way to trace back lineages of family and heritage. Through dialogue with Gilda, Rosa decided she wanted to create a pattern where she repeated the image of an arrow three times. Each of the three arrows represented one of her children. In this print, Rosa’s children serve as a foundation for her representation and her experience as to why she migrated to the US, but they do not encapsulate her subjectivity. In the print, Rosa emerges from this foundation with the sincerity and vision to persist.

The program at TANA, when functioning properly and fully, is generative. Chicanx Studies students from the Poster Workshop engage in building a liberatory educational space. We train advanced Chicanx Studies students to become interns and facilitate the creation of this space in a community context at TANA. Community members engage in dialogue in a reciprocal fashion, being taught by the interns and in turn teaching them. The prints that are produced in the space are evidence of the ideas that have been circulating in the workshop. These prints then serve as an opportunity to facilitate further dialogue with a broader constituency about current visions for transformation and representation.

These outcomes are not quantifiable, measurable, nor do they generate revenue. The outcomes of the TANA program are subjective and oppositional. They resist enclosure as commodities or products for tokenization. The work of TANA is to create representation for community members who have historically been disproportionately marginalized and alienated from the educational pathways that produce knowledge that is deemed empirical. The work of TANA is also to make the university relevant to the local Chicanx/Latinx community—and all communities that have been historically and disproportionately underrepresented and marginalized within the demographic make-up and central forms of knowledges circulated within the university. The work of TANA is the same core imperative that was outlined in the founding document of Chicano Studies in 1969: community self-determination.

An Unresolved Conclusion

TANA is an applied, community-based art program directed by faculty within Chicanx Studies where the merit and promotions of faculty are still strictly governed by publications that are produced through large externally funded grants or through archival research that is published by peer-reviewed university presses. Yet TANA exists as a free program that is open four days a week, 42 weeks out of the year, where the methods that have been established in Chicanx Studies art courses are provided to community residents, many of whom, though the university is physically only 12 miles away, have never visited the university.

There is a precarity in the sustainability of TANA. This precarity is at least twofold. First, it has been precarious to facilitate this work as a scholarly endeavor for a faculty member directing this program. Second, there is precarity in the financial sustainability of this program. In the first, the faculty director, if they are to be tenure-track and ladder-rank, must move through the university’s merit and promotion process in order to sustain their career as an academic. If the faculty director is not in good academic standing with regards to their merits and promotions, then TANA’s programmatic solidity will also be in question. In the second, TANA is a program of an Ethnic Studies department, which requires the ongoing commitment from the academic college or administrative structure in order to sustain the program. The methods engaged at TANA are unique to Chicanx Studies and thus it is appropriate that this program would be administered and directed by its faculty. The community-based art program of Chicanx Studies centers oppositional cultural practice as a means to facilitate transformation. This community orientation shuns the traditional orientation of art departments that seek to gain impact within mainstream art institutions. The communities TANA engages do not have the financial resources to influence university decision making. At UC Davis, for instance, the Napa Valley wine industry is a major donor for the viticulture and enology program and also for broader cultural sites such as the campus’s major performance hall and art museum. Both of these buildings and programs are named after prominent families who made their fortunes in the Napa Valley wine industry. The same discussion could be extended to how agricultural corporations donate and fund initiatives on campus. TANA, in this regard, is an experiment as to what happens when the community served by the university’s academic mission is one without the financial resources to influence its decision making.

While TANA experiences precarity in these twin impresses, it is also a highly illegible form of academic engagement within Ethnic Studies. While community-based art practice was centered at the formation of Ethnic Studies and Chicano Studies at UC Berkeley in 1969, it has largely been excluded from these academic environments since. The irony is that within Ethnic Studies and Chicano Studies, art and culture are central objects of scholarly analysis. The visual and performative cultures that have emerged from community-based art centers and community-based art practices have been and continue to be relevant objects of critique in dissertations and scholarly studies. Unfortunately, rarely are the cultural workers and artists that engage these spaces hired and promoted as part of the ladder-rank faculty within Chicanx Studies departments.

One day in 2007, when I was struggling over the logistics and administrative challenges to gain a lease and entry to the TANA building, I was walking down the stairs that take visitors to and from the Chicanx Studies Department. While walking down the stairs, a senior faculty member in from the College of Agriculture who frames his work as “community development” was walking up the stairs and stopped as I passed by. He stopped me and shared that he had recently read a news article about our development of TANA within Woodland, which provided information on our struggles to gain entry to the building. He held me on the stairs and proceeded to quickly lecture me. He told me that I had no business developing TANA in this subsidized housing community in Woodland. He told me, if he had it his way, UC Davis would do what Columbia University did and build a big wall around the campus. His point, I believe, was to reaffirm the hierarchy of the university in relationship to the broader community. By building a wall around the campus, either metaphorical or physical, one can be insulated from the questions and concerns that a broader public would demand of knowledge produced within the institution. Little did this scholar know, in Chicanx Studies we are border abolitionists.

I recall this incident as a reminder of the tremendous difficulty we had in establishing TANA. In many ways, establishing an off-campus site to engage the local community with our academic methods is not new. The university has a well-established process for engaging local constituencies. These are often through externally funded research or cooperative extension where there is an existing public or private funding stream to instruct and serve industries with new research generated by the scholars. What I have found is that these existing funding structures only apply to communities where there is tangible evidence that a university investment will yield a financial return either through greater external grant funding or charitable donations. TANA exists despite this institutional logic.

TANA is located in Woodland because it is situated on the belief that only through generationally sustained engagement can transformation occur. TANA is not tied to a five-year externally funded grant or to a quarter-long instructional project where students engage a community constituency for a limited, temporal period and leave. Sustained engagement, in a local community that does not have the resources to support such engagement, utilizing cultural production as a means for community representation and praxis is almost antithetical to the university’s funding structure and faculty merit/promotion processes. As Director of TANA and as a senate faculty member, my work at TANA is often categorized as service, unless I can demonstrate how my individual artwork or writing is facilitated through TANA’s programming.

As initiatives materialize to institutionalize “socially engaged scholarship” within universities, the central question that will need to be answered is what constitutes valid research within this rubric. There will be scholars who utilize traditional research methods and tokenize broader communities by resignifying their practice as “socially engaged.” This resignification could lead to an enclosure of “socially engaged scholarship” around methods that maintain the logic and matrix of the university. Here, I ask the reader to look at the work that has emerged over the past five decades within Chicanx Studies and Ethnic Studies to tangibly engage communities that have been historically underrepresented and marginalized by the dominant culture. Chicanx Studies emerged within universities and educational systems to enact a project of total disorder, whereby the existing structures that maintained inequality were broken and replaced by new methods. TANA is an intentional expression of this disorder.

The major tangible research outcomes that are produced at TANA are exemplified by the four screen prints/posters that I’ve shared in this essay. These were produced by community members who have very-little-to-no access to the university, and facilitated by Chicanx Studies undergraduate interns who are mentored and guided by TANA faculty and staff. These outcomes are not peer-reviewed publications or exhibitions. These outcomes are not objective or scientific. These outcomes resist the category “Art.” The importance of these outcomes is not measured by their engagement within the contemporary art world nor within the social scientific research community. The importance of these outcomes is based on what is learned through the relationships created with community members. The importance of these outcomes is based on how community is formed at TANA and then subsequently how community is imagined and created outside of it. The importance of TANA is in the formation of community that continues generating subjectivities and methodologies that challenge the foundation that generates inequality. In this regard, the outcomes at TANA are to be measured by the continual generation of movements so that futurity can be manifested.

Work Cited

Chicano Coordinating Council on Higher Education. 1969. El Plan de Santa Barbara: A Chicano Plan for Higher Education. Oakland: La Causa Publications.

Fregoso, Rosa Linda. 1993. The Bronze Screen: Chicana and Chicano Film Culture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Lopez, Alma. 2015. “Artists as Migrant Workers: From Community to University Teaching.” Aztlán: A Journal of Chicano Studies 40 (1):177–188. Special Dossier on Chicano Art within the Academy.