Abstract

Stories of Solidarity (SOS) is an innovative social media platform and multifaceted research project that overlaps the humanities, arts, social sciences, and computer science. The working group includes academics, activists, designers, and computer programmers. SOS addresses enormous problems millions of workers face today—including low wages, insecure work, and lack of benefits such as health care—through a new platform with storytelling, solidarity building, and advocacy at its core.Since the beginnings of the industrial revolution, groups of workers have relied upon a concentration of their numbers in physical proximity and their ability to communicate to better their conditions of work. Today, many of these conditions have collapsed. The growth of precarious conditions of employment, characterized by part-time work, remote locations, outsourcing, and nonstandard shift changes means that workers frequently lack the shared physical environment of earlier generations and the social interchange that went along with it. Added to this difficulty are the profound changes in media that offer far fewer platforms for broad public social interchange that has been so vital for building public consensus and civic conversation. What was once mass media is now a multitude of splintered, demographically atomized media. Community television and radio have mostly disappeared, and daily newspapers have dwindled considerably. Vital communicative links that have been used for reaching a wide public have dissolved, creating a huge challenge for communication with working people. These changes have created enormous opportunities as well. New forms of media offer a more direct and unfiltered apparatus for communications. The ubiquity of mobile phones and computers means that conversations can occur across borders and time zones, in metropolises as well as remote rural communities. The proliferation of such media creates affordances to increased democratic access to communications tools, allowing many people to be able to be message senders as well as receivers. The speed at which messages can be sent has also been a great boon as well, allowing instantaneous decision making and logistic support. We believe these tools can be used to great advantage in organizing the next stage of labor, not as an alternative to face-to-face organizing, but as a means to enhance our ability to bring workers together to confront the challenges that face them.

Stories of Solidarity (SOS) is a work-in-progress social media platform and multifaceted research project that overlaps the humanities, arts, social sciences, and computer science. The working group includes academics, activists, designers, and computer programmers. SOS addresses enormous problems millions of workers face today—including low wages, insecure work, and lack of benefits such as health care—through a new platform with storytelling, solidarity building, and advocacy at its core.

The Stories of Solidarity project arose from a "hackathon" group formed for the Social Media, Insecure Work and New Solidarities conference, initiated by UC Davis professors Chris Benner and Jesse Drew. The conference was held at the UCLA downtown labor center in the fall of 2012. This conference, and a planning conference held at UC Davis a few months before, brought together a wide variety of on-the-ground organizers active in organizing among the most precarious, low-wage workers, including Our Walmart, Restaurant Opportunity Center, Food Chain Workers Alliance, Warehouse Workers United, and the Day Labor Organizing Network. Established unions that participated included the International Longshore and Warehouse Union, UNITE HERE, the United Food and Commercial Workers Union, and the AFL-CIO. Immigrant-rights organizations were represented by 67 Sueños, United We Dream, and the Dream Resource Center. In retrospect, we believe our ability to bring together such a wide range of vibrant organizations who traditionally have little connection with academia stems from our personal connections and work histories that extend far beyond academia into community and working life. This, plus our intent to collaborate as equals to build concrete solutions to problems, rather than only study and report on them in an academic context, fuels our work.

The conference brought together numerous labor organizers, immigrant-rights activists, and labor scholars to discuss the challenges posed by the rise of “precarious” labor. The hackathon team, initiated by UC Davis professors Glenda Drew (Design) and Jesse Drew (Cinema and Digital Media), came together to create a new social media platform based upon the needs of labor organizers working with workers who suffer from low wages, poor health care, immigration problems, and other deficiencies of our nation’s economy. The SOS team critically asked how the research university can engage with the labor movement in meaningful ways and grew to include students and faculty from the fields of design, computer science, history, community development, technocultural studies, and digital humanities from UC Davis and UC Los Angeles.1 The challenge of working across disciplines was anticipated, but arose in unexpected ways. In particular, the prioritization of attention tended to hover within one’s area of practice, creating three central poles of prioritization that competed for attention—front-end visual design, back-end programming, and the human factors of reaching out to organizers and workers. Perhaps our biggest challenge, though, was confronting a general lack of knowledge about working-class collective struggle. Our research efforts included interviewing field organizers; meeting with labor academics; reviewing labor/employment data and statistics; designing and developing mobile texting (SMS), smart phone, tablet, and web platforms (using html, CSS, JavaScript, SQL, and parsing relevant data from data sources); and conducting user testing.

The project recognizes that social media has become a powerful means for connecting people and supporting social-movement organizing. At the same time, rapid technological change, globalization, and volatile competitive conditions have contributed to growing insecurity in work, in which the workplace is less frequently a site of long-term stability and collective conceptions of work have been eroded as a basis for solidarity. The developers of Stories of Solidarity seek to apply a diversity of skills and ideas to help solve an important social ill that plagues millions of workers in the United States. The SOS project has been built primarily as a labor of love, with hundreds of hours of labor donated in the spirit of solidarity and activism. Even so, the project still needs funding to move forward, and our team has been successful in cobbling together a bare minimum level of funding, which mostly goes towards ensuring students, programmers, and designers get some kind of compensation for their labor. Other expenses have included travel, computer hardware, and domain hosting/online services. The University of California Humanities Research Institute (UCHRI) granted us our preliminary funding for the initial UCLA conference, while an Open Sorcerer Alchemy Workshop Grant from the University of California Institute for Research in the Arts (UCIRA) funded student travel to the hackathon at the conference, thus launching our initial Stories of Solidarity prototype. We have been very grateful to receive additional funding from a range of other sources, including the Center for Information Technology Research in the Interest of Society (CITRIS), the UCIRA, the Davis Humanities Institute (DHI), the Center for Regional Change (CRC), and the American Federation of Labor-Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO). These sources illustrate our interdisciplinary foundations and perhaps also highlight some challenges we have faced about the project, since we don’t fall neatly into traditional boundaries. Are we a tech project? A labor project? An art project? A design project? We are, of course, all of these. We note that while we are extremely grateful for the funding we have received, we also feel we have been denied larger grants due to the nature of our project, which involves taking an active stand for workers’ rights. Our observation leads us to believe that, while the university enthusiastically encourages collaboration with corporations and businesses, it shuns similar collaborations with labor.

No platform like SOS currently exists. A collaborative project built from the bottom up, SOS is the result of a rigorous need-finding process with labor and community organizers to identify desirable tools for organizing and mobilizing precarious workers that do not yet exist.2 Not only is it widely recognized that first-person stories—the words by and of those affected—are highly effective in creating solidarity, informing the public, and motivating political and economic change, but the tools to create, store, and share such stories are either grossly inadequate or missing altogether. Our research has shown that having a platform whereby workers can share their personal stories with other workers and the general public can have a dramatic and positive impact for social change.

Figure 2: Motion graphic overview of Stories of Solidarity platform and use. Courtesy of Glenda Drew and Jesse Drew.

Heightened social awareness can be pivotal in addressing the disparity of wealth in the contemporary United States, particularly regarding the millions of working poor in fast-food restaurants, big-box stores, domestic sectors, agriculture, and other industries that profit by maintaining a precarious workforce marked by low wages, part-time hours, and few, if any, benefits. In the Central Valley of California, for example, job growth tends to be centered around precarious work. With a minimal culture of working-class organization, the economically depressed small towns and communities scattered around the valley ensure a ready pool of labor eager to work two or three jobs to make a living. While farmwork and cannery work have traditionally been one of the mainstays of precarious work in the valley, it is now shifting towards supplying the enormous warehouses that fuel the new global consumerism of Amazon and online shopping. Thanks to recent activism and awareness, many states are moving to raise the minimum wage, and many agree that the first-person stories of workers have been instrumental in swaying the public towards supporting such action.

Because no media comparable to SOS existed, we are building our platform entirely from original code, which encourages innovation, originality, self-sufficiency, and the DIY attitude critical to contemporary entrepreneurship. We believe that coding our own platform acknowledges public wariness of current commercial media platforms that undermine security by mining and selling personal data. Strong visual design is a requirement to earn public interest and we have painstakingly considered our balance between form and content. We have created original branding and have employed visual design strategies that are attractive and inviting to appeal to a wide audience.

Figure 3: Stories of Solidarity screen capture; A brief overview of the SOS platform. Courtesy of Glenda Drew and Jesse Drew.

We take very seriously the ramifications of the “digital divide” that segregates the public’s access to and use of technology. We have researched and carefully considered our audience and their access and use of interactive media, and are working on incorporating all of these findings. SOS is designed for workers, organizers, academics, and the general public. Based on points of access, SOS accommodates low-level input through SMS (because it is widely acknowledged that cell phones are in wide usage among even the lowest-income workers), mid-level input through smart phones and tablets (that includes options for image upload and soon-to-include sound and video options), and a full-featured website with searching, filtering, and following capabilities. The geo-narrative website displays messages using various narrative and visual devices, including a map view (geolocation) and a story view. Coming soon, content can be filtered by categorical schemes including location, organization, and topic. With subscription options, users can follow any set of posts; organizers can collect stories for SMS, blogs, and other uses. Integrating data visualization and information graphics will be another innovative feature of SOS. We plan to layer relevant data to add social, economic, and political context to the personal story in order to deepen understanding of locales, workplaces, and communities. Overlaid grids, for example, will reveal data such as minimum wage, unemployment numbers, race/nationality statistics, language information, voter registration statistics, and more.

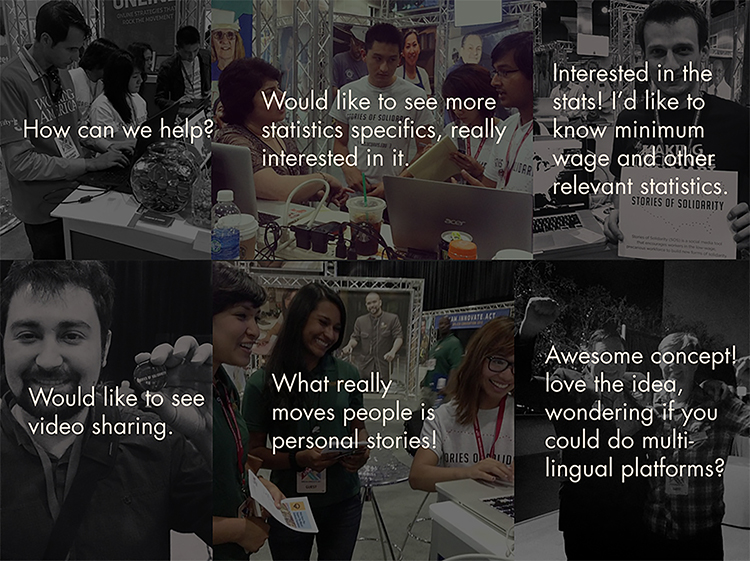

Stories of Solidarity is more than a research project; it is a tool to address problems of poverty and inequality that will encourage action at the grassroots level. Bringing together the resources of academics and technologists, SOS aims to serve a sector of the public that is frequently overlooked by our institutions of higher learning. Based upon a strong belief in democracy and the importance of grassroots communication, SOS is a platform that will provide communications, support, and information to enhance civic participation. The SOS project has already been tested among a large cohort of potential users and advocates, including feedback from hundreds of labor leaders and workers from the United States and around the world at the AFL-CIO convention (where SOS was prominently featured), the UDC conference (Union for Democratic Communications), IAMCR conference (International Association for Media and Communication Research), and many universities and labor meetings. As the principal developers of SOS, we see this project not as an anomaly, but as a strengthening of our research and practice at the university—using our skills in technology, electronic media, programming, and interactive design to meet the obligations of the public university to serve the public, particularly ignored working-class communities. The support for these goals among our departments, colleges, and the administration has been mixed, ranging from enthusiasm to hostility to indifference. As many community-engaged scholars recognize, writing a book, regardless of its impact or readership, is still rated higher than creating work that will impact the lives of many. There is no guarantee that building a successful collaboration with working-class communities will be recognized and awarded on campus, but in any event, the level of satisfaction and joy can be easily found elsewhere, among the community one serves.

At its heart, a worker’s organization is a communications system, a bond of solidarity forged by conversation, debate, discussion, commitment, and agreement among workers that enable them to take collective action. It is no accident that railroad unions were among the first nationwide modern labor organizations, thanks to the extensive network of rails that connected workers in the industry across a wide geographic area. Labor has always tried to take advantage of new communications technologies, from the early telegraph to radio, television, and the early internet. Today, we live in a world of rapidly changing technologies, and labor organizations have been struggling to keep up with them and the new conditions they create. In many cases, labor activists have used them to great advantage, while others eschew them, considering them gimmicky and of not much use. We believe that labor should pay greater attention to these tools and devote the necessary resources to share positive experiences, avoid fruitless ones, and develop new applications and means of communication in order to combat the challenges working people face in the new conditions of precarious work. We note that while labor solidarity has suffered recently, many new social movements have had great success using social media tools in building new solidarities based upon race and national origin, gender, sexual orientation, and environmental concerns. The Stories of Solidarity project is committed to creating new academic ties with working-class organizations to create new forms of solidarity in order to address the extreme inequality and hardship faced by working people around the world.

See the platform for yourself here: http://www.storiesofsolidarity.org.

Notes

1 Stories of Solidarity has been created with a shoestring budget and has included many contributors. The initial UC Davis team (2013–2014) consisted of students Kat Fukui, John Haffner, Vivian Ho, Jack Leng, Joyce Lue, Tristan Schoening, Liz Shigetoshi, and Ashish Subedy. The UCLA hackathon team consisted of faculty Miriam Posner with students Leslie Bloomfield, Anthony Bushong, Sophia Campos, Amy Hawkins, David Kim, Joanna Lo, Celso Mireles, and Monit Tiyagi. The 2014–2015 team consisted of UC faculty Ken Jacobs (Berkeley) and Robin Delugan (Merced) with Davis students John Haffner, Michelle Huey, Emily Isaac, and Elizabeth Pizano; Merced student Lidia Pavon; and independent developer Josh Levinger. Spencer Mathews (student, Davis) and Iris Xie (community member, Davis) contributed to the project from 2017–present. Glenda Drew and Jesse Drew have been the principal investigators from the beginning.

2 Certainly, there are social media sites or story-sharing projects (such as the Mobile Voices project) that aim to empower workers, but there are none on the scope of SOS, a dedicated multi-input platform, programmed and designed from the ground up, that crowdsources workers' stories directly.