Abstract

Art of Transformation (AoT) is a public media project that links cultural organizing practices with new media research. At its core is the development of an open source software application, MapTu, which establishes a persistent, crowd-sourced platform for gathering, deliberating, visualizing, and sharing diverse knowledges within a 3-D digital space. Use of the tool, however, is enmeshed with an urgency of collaborative inquiry and connection. The goal is to expand communities’ capacities for storytelling and cultural development, to cocreate shared visions of our world. AoT emerged from the 2015 Imagining America conference, but the work continues to evolve through collaborations with communities and organizers. In its early phase, AoT collaborators asked, Would AoT illuminate unseen issues, or strengthen connections for social change? Now, AoT raises as many questions as it answers, recognizing that cultural organizers must play an integral role in shaping urgently needed new virtual public squares.Media Stories

Our stories have changed. Not only in Baltimore, but probably everywhere in the US. The optimistic attitudes that permeated mainstream media after World War II have dissipated into decades of intractable challenges and political dysfunction, perhaps because life is no longer improving for most people. Today, we are left wanting and needing stories whose form and content reflect our evolving ideas about who we are, what is true, what is smart, and what is right—stories that network and change and connect at the same speed as the world around us. Art of Transformation (AoT) is a Baltimore-based public media research project creating a space to imagine and develop such stories. It is a hybrid of new media, software development, and cultural organizing. Those involved in AoT approach cultural organizing as a form of engaging people within their own social contexts, working through power dynamics, and creating cultural products for social transformation (Cammarota 2008). Cultural organizing done right should spark a self-perpetuating movement of equity, empathy, and social justice through creative cultural action (USDAC, n.d.). AoT is currently made up of university faculty, staff, and students; organizers; community scholars; artists; and individual residents of the city who are committed to unlocking the power of creating both new stories and new ways to tell them through media.

Until recently, the pinnacle of good thinking and smart action was to dissect a problem with thinly sliced disciplinary thinking, seek its narrowest and most precise definition, and look for a single cure. We wanted the best perspective, an efficient and effective solution, and one truth. But now, the story of how we should address complex challenges is changing. We are increasingly more comfortable seeking out diverse perspectives and entertaining all relevant data, information, ideas, and truths at the same time. This is not just an academic trope. In fields such as health, for example, we know now that improvements are not about finding a single pathogen, but rather about understanding interconnected social determinants of health and an expansive ecology of interacting factors that impact each person’s well-being (Krieger, Williams, and Moss 1997). In our language too, the "think different" lexicon has expanded to include endless variations of "It's not one thing;" "It's not either/or, but both/and;" "Break down the silos;" "Seek novel connections and ask the other question;" and "Creativity and insight happens where knowledge and ideas intersect." We want to "complicate" or "trouble" simplistic narratives and single stories. We want to see not one, not three, but all the factors that impact an issue. We like multiplicity, plurality, and multiple knowledges. But like old stories that no longer ring true, the tools we've been thinking with—developed when reductivism reigned—are holding us back.

With AoT we are asking: What media—as a tool for collective thinking—has the capacity we need to create positive social change? What will it actually look like, and how will it work? Nearly two years into the project, and having completed phase one, we have no answers. But our questions and our processes have improved. We've anchored our media research in communities that are usually on the receiving end of new media forms—we want to upend the “receiver” role in technology development, much like cultural organizing upends our traditional understanding of knowledge hierarchies. One community, in particular, bookends the evolution of AoT. Morrell Park is a small community in southwest Baltimore that seemed complicated when we first drove through it. We had no idea. As an attempt at creating new media, we started doing interviews on the street, and a year later, we visited the community center for additional interviews. Unfortunately, when we screened our work for neighborhood residents, the response nearly cost the university's relationship with that community. The stories that emerged from the interviews and that we edited into a film were not representative of the stories those residents felt they were trying to tell. We were left having to earn back their trust, to listen and learn things from the experience that were not initially obvious. And in that process of correcting our missteps, community responses and our own recursive reflections revealed the centrality and necessity of intertwining cultural organizing and new media practices.

AoT grew initially out of earlier research at UMBC's Imaging Research Center (IRC), an experimental media lab looking to improve the use of new media technologies to achieve prosocial outcomes. Over the past decade, experiments in the lab increasingly point to culture and identity as promising and flexible determinants of people's collective and individual choices. Researchers from a wide range of disciplines increasingly see culture and identity as responsive to stories, images, and other forms of expression. There is little doubt that media has a powerful effect on what we think, how we feel, and how we act, both collectively and individually (Bimber 2012). So, cultural organizing through digital media seems to be a promising path. But, just as all information has political implications, all forms of media are rhetorical as well—both shaping and filtering content and meaning-making. Art of Transformation and the new media software it uses are a response to some shortcomings of contemporary media. Sales of digital devices suggest that people approve of media technologies, which are seen as the crown jewels of our consumer society. Yet, while some believe these technologies will serve to enhance democracy through access and voice, Gallup polling shows that many consider the media our current technologies deliver to be the evil that might in fact end democracy altogether (Swift 2016). Are we sensing that the ways media treat us and our ideas are not helpful in effecting significant change? Look at the way knowledge gets sliced up. From books to TV, from PowerPoint to social media, our devices bring us one thing, in one voice, at one time. A book might have 500 pages, but we can only see two of them. Smartphones are like electric drills—they make a hole so we can glimpse a narrow ray of reality.

Information ends up segmented and segregated. When the slide changes, the page turns, or the new tab opens, the previous one vanishes. We can't draw novel connections between things we can't see, and we struggle to visualize complex relationships in our minds alone. The result is myopia.

Admittedly, seeing the whole landscape can be overwhelming. There is comfort in simplicity and certainty. Those ambiguous, complex, and connected issues that are always part of the human condition are what we are most anxious to put in a box or take off the table altogether. It's only logical that the so-called "wicked problems" or "grand challenges” we've left ourselves with are those that resist reductive, disconnected thinking. Part of what we are aiming for with Art of Transformation is to provide a tool that encourages comfort with uncertainty and vulnerability, a playful, serious space that we hope can facilitate "systems thinking."

Current media forms don't only isolate ideas, they isolate people as well. Think about the question routinely asked when media is being planned: "Who's your audience?" It sounds smart, but really, it means how can we divide people up? How would any of us answer that question if we were writing a religious text, constitution, or Huck Finn? Our answer might have to be: "People who can read." Broadcast news media has devolved into partisan echo chambers as well (Garrett 2009). Social media, too—once heralded as the tech of revolutions—has us circumscribing our “tribes” within even smaller, like-minded circles. Most academic publishing, while useful, seems almost designed to avoid becoming part of the broader cultural discourse. The current state of media and communication makes it hard for people to come together. In an era of dwindling public space, and the near disappearance of social clubs and organizations, where do we go to deliberate, build consensus, or cocreate shared vision across social or political divides?

AoT is both a media research and cultural organizing project that offers public space for collaboration and deliberation. To succeed as envisioned, it depends on relationships, and increasingly, the work of UMBC faculty who have committed to building relationships with community partners. This effort reached a new plateau when UMBC was chosen to host the 2015 Imagining America national conference for "publicly engaged artists, designers, scholars, and community activists working toward the democratic transformation of higher education and civic life” (IA 2017). A well-loved annual feature of this conference are site-specific workshops designed to get conference-goers out into the host city. UMBC faculty and students, along with community partners, sought to expand these workshops and use the organizing process as a way to build cross-city knowledge and connections. Planning meetings were held for months with arts, humanities, and advocacy groups from around the city. We opened each meeting with the promise that this conference was not an end in itself, but a way to build the relationships that would be the basis of ongoing work long after the conference was over. It helped. People came. Things were going well. Then, on April 19, 2015, after only two of the meetings had been held, Baltimore became the latest, in a growing list of cities, to report the murder of a black man as the result of his unfortunate encounter with police. A few parts of the city ignited in flames, but most ignited in anguish. National and local media painted Baltimore with their own brushes and saw what they wanted to see. Politicians did the same. Young people involved in the uprising were called "thugs," though most had simply emerged from their school buildings to find their buses canceled and themselves stranded in a world upside down and out of control. The death of Freddie Gray had hit the city as another violent cloudburst in a storm that has raged here for centuries.

As these events were unfolding, we were planning our conference. We met in a classroom at Morgan State University on April 21st, two days after Freddie Gray's death. The room was full; the mood was subdued. The stakes for this conference had become higher. What do the arts, humanities, and design have to offer people dying from injustice? A conversation tinged with rage, sorrow, and urgency bonded us in our determination to work differently. We discussed our fractured city—how decades of growing wealth inequality and race-based discrimination in housing and education, employment and health, politics and culture, made Baltimore a city of fault lines that divide us into north and south, black and white, rich and poor. The relationships, aspirations, and commitments that grew out of these meetings became the foundation of Art of Transformation. The conference was a great success, setting new records of participation despite landing on three of the rainiest October days Baltimore had ever seen. Four major universities and no fewer than 50 organizations were actively involved.

After a post-IA conference gathering and celebration of over 50 people, and a couple of months of rest, we put out a call for those involved to come together again. About 20 people showed up, but it was enough. We decided to call ourselves BIG (Baltimore Imagining Group) and we would think big. Our collective community-university agenda evolved to include addressing racial inequities in arts funding, challenging the historically unequal nature of university-community relationships, and recognizing media as central to social change efforts.

Figure 2 Video courtesy of UMBC Imaging Research Center.

AoT Emerges

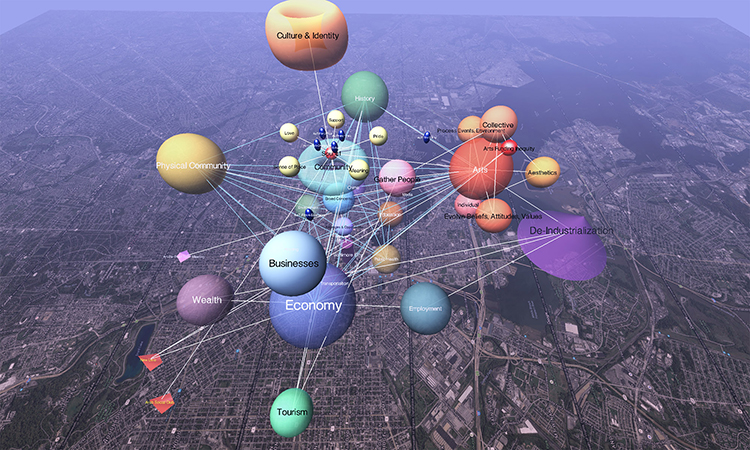

We envisioned a new form of media—one that would support cultural agency and organizing. We would create it from the ground up, working with community organizers and using cultural organizing strategies such as arts-based practices that include filmmaking, storytelling, theater, and design processes. To signal its departure from current media forms, AoT would look different by symbolizing, even at first glance, comprehensivity, complexity, and multiplicity. It would leverage software, called MapTu, already being developed at the Imaging Research Center at UMBC as a tool to enable systems thinking.

We hoped to build a virtual Baltimore whose landscape would be covered with living monuments to our cultural assets and visualizations of how our collective challenges are connected, what we envision, and how we are organizing for change. It would be a persistent, open, public space for discourse, collaboration, and cultural engagement. It would be a response to, and remedy for, years of the one-day, hit-and-run conferences and meetings that yielded very little, and left the city with little new vision or plans.

Since its inception, MapTu is continually being developed to combine geographic mapping, conceptual diagramming, and media hosting. It provides users the ability to make 3-D virtual spaces with maps as the ground floor. In these spaces users can create 3-D diagrams that visualize data and information, knowledge and ideas, and the relationships between them. Users can embed films and other media into the forms. (Think 3-D Prezi, for those who know that web-based presentation software.) And importantly, it allows people the ability to work in the same space at the same time—like a Google Doc, only visual.

As we continued the cultural organizing work of the IA conference, we wanted to start using the software, but it was not ready for prime time. Our solution was to bring the community into the development process. Instead of people being handed software developed for them, communities would be part of the development process nearly from the start. They would be insiders involved in research on an ambitious and innovative software project.

The software was for mapping ideas and capturing stories that initially relied on filmmaking, a significant capacity of the IRC since films are also the most popular kind of online content. We would work with communities in west and southwest Baltimore, one at a time, to record residents' stories by filming semi-structured interviews and story circles. The films would be edited into something that could be watched within a reasonable amount of time, and embedded in 3-D diagrams geolocated within the AoT space in the MapTu software. While not involving a rigorous process of coding analysis in this first phase of AoT, the approach would essentially be ethnographic with elements of participatory approaches, oral histories, and phenomenological lived experience conversations. Local events would be held where interviewees and the broader community could see the resulting films and other work. The hope was to spark discussions that would help us learn more about our communities, and importantly, how they felt and thought about what we were doing and how it could be more useful.

Guiding our community-engagement practices, several people on the AoT team have committed to the tenets of Critical Participatory Action Research (CPAR), as taught and promoted by the Public Science Project at the City University of New York (CUNY). The ethos of CPAR is that research done by universities in communities should be collaborative, engaging community members as co-investigators with the ability to initiate, shape, and disseminate research, and that in the end, any benefits should be reciprocal. Given the time this work requires from all participants, reciprocity is no small commitment. Salaried university employees often have more stable employment and higher incomes and benefits than community organizers or leaders of arts organizations. Project participants have diverse life conditions that must be respected and accommodated. Academic careers and university reputations are advanced by conducting and publishing community-based research, while benefits to the community may be far less direct and require sustained involvement from all partners in order to come to fruition.

The early project work led by the university was also complicated by the early stage of the MapTu software development. It was still too difficult for most people to use, and we lacked enough money to pay community-based film producers. We had raised some money to pay participating community partners by joining with a project called Baltimore Stories: Narratives and the Life of an American City, that, with our help, had a Public Square grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. But those dollars would not go very far. As a result, university people would do a disproportionate amount of the work in hopes of "priming the pump," by creating something visible so that people could see and judge its potential value. Doing so much ourselves was a compromise of our participatory commitments and an imperfect solution, but we could not see a way around it without waiting indefinitely to get started. If people liked what they saw of the project, we hoped that in later phases community members would take over the project entirely, with UMBC faculty, staff, and students providing support as needed.

A First Year of Organizing

We heard positive reactions to our plan and the new media form we were promoting from some partnering organizers. And while we were worried initially that we would simply confuse people with such a novel way of visualizing aspects of a community, we were encouraged by their excitement. They thought the AoT space in the MapTu software was cutting edge and futuristic, and that the ability to visualize connections and relationships, instead of simply imagining them, was promising. Perhaps, we thought, the limitations of our siloing media forms is something sensed broadly, at least by those with a certain "radar" for tools that could serve social change work. Subsequent discussions have suggested that a key to the project’s compelling nature is the access it offers to community members who have most often only consumed technologies. Instead, it provides an opportunity for them to actually leapfrog the pace of technical innovation, to perhaps shape a new technology from its inception, in ways that directly reflect and work for their communities.

The first community we would work with was in the Walbrook area of west Baltimore. Mama Kay Lawal-Muhammad and Mama Rashida Forman-Bey are Founders and Codirectors of Wombwork Productions, an arts organization that uses theater as a method of social practice to raise the consciousness of neighborhood youth, give them a place to be creative and inspired, and in the process, keep them safe in the afternoons and on weekends. The AoT team had strengthened our relationship with the Mamas when they coproduced an IA conference workshop with UMBC theater professor and AoT associate Alan Kreizenbeck. With them, we planned to redo this powerful workshop, but this time, we would film it. The workshop combined ideas and rituals from the international Virtues Project, with small-group storytelling and listening practices structured to reveal people's diverse personal experiences with race. It culminated in short theater performances that embodied and expressed what was said and heard in the story circles.

On the night of the workshop, a few months after the IA 2015 Conference, the tensions and traumas from the death of Freddie Gray were still fresh in everyone’s mind. The Mamas began the night with a moving ritual of naming and expressing our individual virtues for the larger group. The Virtues rituals that opened the workshop primed everyone for six storytelling circles, where each person would tell a brief personal story about race and listen closely to others. It meant that throughout the room, six people were always speaking at once. From a filmmaking point of view, it was cacophony. Wombwork leaders had rejected the idea that each speaker would hold a mic up close—too distracting. Instead, six student filmmakers simultaneously and silently moved around the outside of each circle, capturing people's deeply reflective recountings, attempting to isolate the speaker's voice without intruding. The stories complicated prevailing narratives about race, and the evening ended with performances.

Figure 4 Video courtesy of UMBC Imaging Research Center.

A few months later, an event was held at Wombwork Productions to screen the films and show what we could of the software. There was a good turnout, perhaps 50 people—in part because of the delicious and healthy meal prepared by Mamas Kay and Rashida. At the end, our panel of theater directors and media makers answered questions. There was appreciation of the process as seen in the films, and there were urgent, critical questions: Who made the decisions about what ended up on the cutting room floor? How were decisions made regarding whose stories warranted subtitles to clarify hard-to-decipher audio? How diverse was the editing room? While the questions were answered—more white than black interviewees were subtitled, the editing room was quite diverse—that didn't address the fundamental concern. The power to edit people's words did not rest well with some people of that community. There was not a single question about the visualization in the software.

During the earlier workshop, people had been telling their stories and participating in theater together, in the same space, at the same time, affirming one another's virtues and performances. We listened to each other’s self-realizations and moved together through our different imperfections. By contrast, what was presented on the night of the subsequent screening was a final product. And by comparison, the event was not interactive. People anticipate passivity with mainstream media, but AoT was supposed to be different. Our attempt to "prime the pump" with our own effort turned out to be, perhaps predictably, problematic. In their own practices, Mama Kay and Mama Rashida were able to “create a sacred space for people in the community to be able to talk about race” (K. Lawal-Muhammad and R. Forman-Bey, unpublished data, June 23, 2016). But that was a rare experience for most people. And online, nothing is sacred anymore, especially in platforms that are intended to connect us. So the challenge to AoT was, and continues to be, how will we create and maintain sacred spaces and attend to our collective responsibility for cultural organizing that assures virtues and values-based online space for community building? We realized that when AoT is no longer in our hands, it must not be only about representing cultural artifacts in a virtual space, but rather about continually connecting and reconnecting people for whom those artifacts have meaning. It must be as participatory as possible.

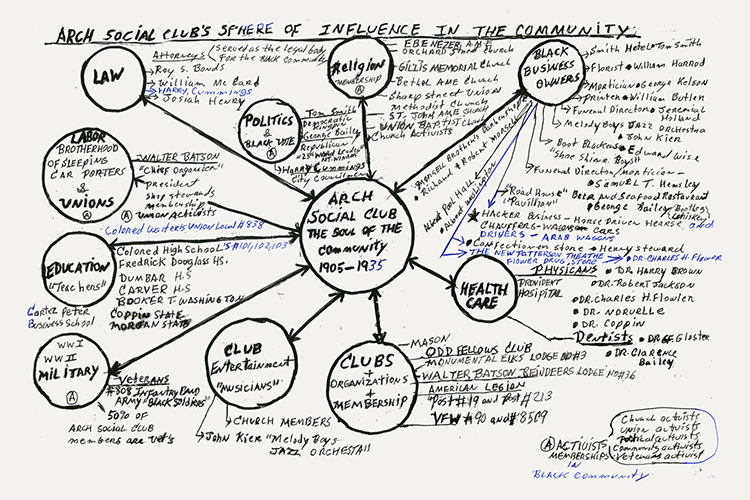

A month later, on a dark evening with torrential rain and horrid traffic, 50 people got themselves to the Arch Social Club in west Baltimore’s Sandtown/Winchester neighborhood for a presentation of interviews and conversations we'd organized in previous months. The event was cosponsored by Culture Works and the United States Department of Arts and Culture (USDAC). The Arch Social Club is the oldest black men's club in the US, with a 100-year history of enormous influence throughout Baltimore, especially in the early twentieth century, when even more than today, there were two Baltimores: one white, one black. Our community partner and AoT producer, CultureWorks cofounder and Director Denise Johnson, was the first woman member.

Denise, a coauthor of this article, connected us with people and institutions that are the heart and soul of this historically important and yet disinvested community. She also designed the evening the work would be screened for the community, steering us away from our tightly scheduled agenda and opening a space for people to be in community and participate in a cultural event—a cultural action—for sharing films and images, dancing to an excellent DJ, eating great soul food, and engaging each other in conversation.

The interviews Denise thoughtfully orchestrated unraveled a narrative that mainstream media had endlessly repeated regarding this region of the city. The people who agreed to be interviewed on film ranged from 25 to 65. Some were involved in business, community investment, and culture making, while others were simply residents.

Figure 5 Video courtesy of UMBC Imaging Research Center.

These stories, presented in six films embedded in a 3-D diagram organized around central content themes, counter the dominant negative media portrayals of African American communities that judge and distort people’s experiences. Instead of describing a community through the traditional indicators of income, education, crime, or health, when the community was asked to tell their own stories, they painted a picture of joy, meaningful histories steeped in culture, and a thriving community. These stories counter traditional media that allows "problems" to dominate a community's identity. And by doing so, the community stories show how such traditional media methods work to hide the very systems and structures responsible for a community’s challenges.

In the conversation sparked at the Arch Social, people strongly expressed feelings that mainstream media, as seen during the recent Baltimore Uprising following Freddie Gray's death, only exacerbated residents’ continuing frustration with chronic disinvestment and danger from police brutality in their neighborhoods. We heard the following comments from various participants who did not identify themselves: “Media has no moral compass. It is not focused on what people need. It hides people who should be accountable.” “Media hooks us on the negative and it becomes something big. They don’t tell us what the positive work is that people are doing.” “Media should have a code of conduct!” “As human beings we have been dealing with a lot . . . anger, despair, sadness. We have to counter the negative narrative by doing cultural actions. We are trying to reimagine our narrative.” Social justice activist Michael Scott asked, "What declarations of possibility have the power to inspire [us] and transform the city?” (Participants’ feedback, unpublished data, July 28, 2017). The discussions then turned to collectively imagining possibilities for future investments and citywide interest in west Baltimore and its residents.

Several audience members expressed appreciation for the media aesthetics and navigation of the virtual city and cultural mapping they saw in the AoT space of MapTu, and its ability to enlarge and collapse ideas in the space so that both individual and community voices could be seen and heard. Kaleb Tshamba, the Club's historian, saw how the software could help him amplify his own historical concept map (below) of the enormous influence the Arch Social Club had had, going back to the early twentieth century. AoT has since begun bringing Kaleb's research into the AoT virtual space.

There were challenging questions as well. How will the software make sure that those in power are not just watching, but really listening to our stories? How will we connect AoT to other important and positive work being done in the community—work not discussed in the films?

Upon later reflection, the essential questions from this community, voiced in many ways, were: How might this new media help to turn around decades of disinvestment following the "King Riots" in 1968? What incentives do mainstream media organizations have to listen better and tell broader, deeper, and more complicated stories, when telling tales that simply confirm beliefs, attitudes, identity, and culture are a solid business model even for so-called public media? How can new stories and the connections between them challenge investment practices that simply multiply wealth and maintain power for a few, instead of delivering investment where it is needed and owed to many? These questions implicate capitalism in the form that our society and media industry currently practice it (money goes where money grows), though that did not come up explicitly in the conversation at Arch Social. As producers tried to imagine how AoT could manifest what was going on in that room, it seemed clear that future efforts would have to connect people and their work and ideas, or become just another silo. The project would have to attract those willing to explicitly voice righteous anger and speak truth to power in the service of critiquing media practices and creating new kinds of knowledge useful for building communities everywhere in this deeply divided city.

As we turned toward south Baltimore, our approach would again be different. The industrial area of south Baltimore is home to communities where people, once left high and dry by deindustrialization, are increasingly working together to counter the effects of disinvestment and environmental trauma. There was no need to seek out and film new stories, as several UMBC faculty and their students had already been working in these former steel and chemical production neighborhoods. Instead, AoT would act as a kind of glue, pulling their materials together, mapping the content in the software, and staging a different kind of event under the direction of artist and UMBC Visual Arts professor Stephen Bradley and community organizer Greg Sawtell. An excellent arts center in the area, the Chesapeake Art Center, would host the event as a variety show, featuring films, poems, stories, and music that responded to the challenges the Sparrows Point, Brooklyn, and Curtis Bay communities faced in the wake of the changing economy of the late twentieth century. Prominently displayed that evening would be an art exhibit, curated by Bradley, that included work by community members about their communities.

Once the event began, Sawtell remarked, “The first part of this program has been about art that speaks to and reflects conditions people are dealing with. [The remainder] will be about taking complexity and trying to make connections and get a sense of it all and then figuring out what we can actually do together” (G. Sawtell, unpublished data, July 28, 2017).

Presenters’ stories chronicled what it felt like to lose an entire way of life when factories that had employed thousands disappeared. Jerry Ernst read his story from the book, The Heat, about working in the steel mills and seeing a coworker die in the brutal conditions. UMBC faculty and students presented their art, oral histories, and storytelling archived in the Baltimore Traces Project, which Nicole King, one of the Traces creators describes as “dynamic social spaces in which scholars and residents work together to frame questions, conduct research, and preserve urban places” (King 2014, 425). We screened a film made by the New York Times about Destiny Watford, a local young woman who had won the Goldman Environmental Prize in 2016 for organizing work sparked by her attempt to protect the health of her family from dangerously high levels of air and water pollution in South Baltimore. Destiny led cultural organizing efforts to stop the construction of what would have been the country’s largest trash incinerator (Williams 2015). She took story-filled performances to the school board and city council meetings and led art-filled marches to the proposed incinerator site. The promise of profits could not withstand the fierce cultural organizing against the site, which resulted in investors and policymakers pulling out of the project (http://www.goldmanprize.org/recipient/destiny-watford/). Destiny’s story connected to other arts-based efforts (just as the Arch Social audience urged), including the 20/20 Vision for Baltimore campaign (http://www.unitedworkers.org/20_20). Throughout the evening performances, AoT visually illuminated the synergies among efforts in South Baltimore and other communities. This experience affirmed the role that the MapTu software could play in connecting communities in Baltimore that traditionally do not interact, around not only social injustices, but cultural celebrations as well.

Figure 7: The Chesapeake Arts Center, AoT event. Slide show courtesy of UMBC Imaging Research Center.

When a person travels from the city to UMBC, located just outside its southwest border, she or he might go through Morrell Park. It seems like a neighborhood in transition between some past heyday and a complex and unforgiving present. Many main-street businesses are closed and groups of young people, not in school and seemingly without jobs or destinations, congregate in front of the vacant houses and boarded up windows. Beyond Washington Boulevard, the main street, sit block after block of WWII-era row houses—most, but not all, well maintained. On one end of Washington Boulevard, a white senior citizen can be seen working in her garden with two little black children. Next door, holiday decorations compete for yard space with Ravens (Baltimore's football team) flags. A block away, homeless people panhandle and dealers run shop in the convenience store parking lot. In interviews conducted over a year and a half, we would learn that the Jekyll and Hyde character of Morrell Park was not an illusion, but reflected deep divisions within what had once been a relatively homogenous and stable white, working-class community.

In fall 2015, we started filming interviews on the streets of Morrell Park. We didn’t know anyone there. We moved through the streets with a big professional-looking camera on a tripod. It was designed to draw attention. We spoke with whomever approached to ask what we were doing. We described the project and asked for an interview. If granted, we asked people: "What's it like being you and living here?" and "What do you wish it were like?" The initial street interviews revealed some hard luck stories to be sure, but mostly ambivalence. There was conflict, under the surface—some of it racial. We then sought a community partner to help us reach a broader range of people. The organizer of the Morrell Park Community Association said she was in a long-term struggle to save the community from “bad influences.” Her perspective was strong and singular. An association meeting revealed far less diversity there than in the community itself, so we began to look for additional places to hear other perspectives. The community's youth arts organization was doing great work, but the people seemed overwhelmed with their ambitious current efforts, and perhaps somewhat suspicious of our university-based motives. We finally partnered with the new Morrell Park Community Center, full of after school programs and recreational leagues, and where black city employees were working with predominantly white senior citizen advisors and volunteers who were well-connected with the Community Association group that had fought long and hard to get the place built. We filmed a meeting of the center’s advisory board. It was cordial and constructive, with the only visible negativity being criticism of the city for not building the center's parking lot. We ran interviews in the afternoons—mostly with parents picking up or dropping off kids to the center, and with the seniors from the Morrell Park Community Association, who met at the Community Center regularly. Seniors talked about how the neighborhood had gone downhill. They feared young people roaming the streets, or how those who had inherited homes and then rented them out to transients had “shirked their neighborly responsibilities.” One such "transient," who had come to Morrell Park to stay with her parents after losing her young husband, had her own concerns. She worried her children would be hurt by knife-wielding kids at the local school. A young high school student spoke about the destructive attitudes and behaviors at school. It seemed no one felt safe in Morrell Park. Everyone was clear that Morrell Park was struggling with significant issues, but they saw the issues differently.

AoT producers edited interview footage, then visualized themes in the map. In late 2016 it was time to show the community what we were up to and what we had learned. The event, to be held at the Community Center, was well advertised, at a convenient time for parents, and promised free food. Attendance was good, though dominated by Community Association members and affiliates; the kids and parents we had interviewed at the Community Center didn't show up. Though they'd been cooperative and somewhat enthusiastic before, the center's staff kept their distance from the event. After the film screening, the members of the Morrell Park Community Association spoke up to object to what they saw as a negative portrayal of their community. They felt it failed to emphasize positive efforts and commitments to rebuilding Morrell Park that included Little League parades, Saturday community clean-ups, and winter clothing drives. There was an extended silence until one young man, whom we didn't recognize, but clearly the association members did, got out of his seat. Looking uncomfortable, he spoke with exasperation, saying that things in Morrell Park were actually far worse than the film had shown. In his mind, the community was a wreck and there was no plan to make it better, and in his eyes, there was no hope. As we had at the start of each of the evening events, we reiterated that the film was not, at this early stage, intended to represent the community to outsiders, only a way for the community to hear one another’s perspectives. Even as those words were being spoken, it was clear that the film's mere existence was hard for many to tolerate. They didn't want others’ truths; they wanted positive representations. This was their community that we were talking about. Reflecting back, the AoT team realized that the importance of this lesson cannot be overestimated.

As much as the familiar medium of film brought out divisions, there was enthusiasm for what people saw in the visualization software. One community member was outspoken, suggesting that this was a futuristic tool that could be pivotal in helping the community identify its needs and connect with other communities who might have similar challenges and useful ideas and practices. Nonetheless, we left the event knowing that we'd put some budding relationships at risk.

We returned to Morrell Park for several more interviews at the suggestion of the most active member of the Community Association. Why not? We couldn't help but learn, and we felt we owed them a deeper inquiry. We re-edited the film into three shorter and more positive films, and were granted permission to share them in the AoT virtual space at a Community Association meeting—the venue dominated by our biggest critics at the previous event. It was a good-sized crowd and people were pleased that university people were taking the time for them and honoring their feedback. They reacted positively to the new films and, once again, to the software as an easy-to-grasp picture of their community they would want to use themselves.

Figure 8 Video courtesy of UMBC Imaging Research Center.

Reflecting Back, Looking Forward

Through these first efforts, what have we learned about introducing communities to an unfamiliar media concept, and the practices that go with it? Bringing software to community leaders and residents so early in its development could simply confuse and frustrate people, and sometimes it did. Its purpose could also be confusing. AoT offers no direct revenues or profits, it's not primarily about self-expression or marketing, it does not provide "the news," so what is it? We were proposing a solution to a problem not many people recognized. Still, despite some significant critiques, we also heard enthusiasm and encouragement. What we did not hear is that we should stop. So, we recommitted ourselves to the complex yet critical dialogical possibilities of AoT.

The media criticism that helped germinate the project centered on the structural problems of current media's ways of fracturing knowledge, dividing people, ignoring stories from diverse communities, and disabling agency. While related, those are not the same as the concerns held by people in the communities we engaged with. They were much more focused on the way the content of media is distorted and how injustices are hidden, and they were suspicious of us as people who might do the same thing. Those living in communities ignored or maligned by media feel the impact of the perceptions media has created. People’s strongest critiques were about representation in our editing room and in communities. And their most passionate questions were about how the software could help them.

Those involved in AoT must now look at our ideas and see whether and how they could serve to address the one-sided wrongness of media stories and the need for tools that support people in communities to solve urgent problems. Our hypothesis is essentially that our current media forms make distortions inevitable—that dicing up ideas and groups of people obscures structural injustice and allows inequities to be normalized. Current media does almost nothing to help people develop useful knowledge, articulate shared vision, or organize. That said, the kinds of participatory practices needed to create democratic media—values we held dear—were compromised in this first phase of AoT. Community members did not make the media. However, the different perspectives that emerged in Morrell Park made it clear that regardless of whether we are in the process or not, practices of representation will be contested. They will be multiple, not singular, but that alone will not resolve conflict, since for some people, multiplicity itself is controversial. So the software and cultural organizing practices must attend to creating sacred, safe, and brave spaces, clarifying values and principles, and developing practices to support multiple perspectives and deliberation. In the aftermath of events in Charlottesville, VA, is achieving the broadest possible representation even still the goal? Would white supremacists and Nazis be welcome in the AoT space of MapTu?

Perhaps what the team feels best about is our continued commitment to flipping the practices and narrative on the way people in power shape new technologies "in their own image." The "public" is generally granted access to new technologies to the degree that public access serves the purposes of creators, or as the technologies are well on the way to becoming obsolete. These practices have a long history and uphold continuing social injustice (Banks 2005, 40).

In the next phase, the software will be ready for community members to use, if not immediately on mobile (our longer-term goal), at least with laptops or computers available everywhere in Baltimore through the nationally recognized Enoch Pratt system of public libraries. The software's stability and interface are undergoing significant upgrades in the fall of 2017 that will make it much easier for people to use. A robust back end is being developed that will allow all manner of quantitative data to flow into MapTu (such as ArcGIS, social media analytics, and census data) to be visualized based on user-defined parameters. Longer term, the data visualizations themselves will serve as a graphic user interface for data mining and predictive modeling. The IRC group developing MapTu has partnered with the Center for Hybrid Multicore Productivity Research (CHMPR), a National Center of Excellence sponsored by the National Science Foundation (NSF) to develop ways of combining both qualitative and quantitative data in virtual 3-D environments for collaborative analytics. Why does this matter? Why big data? Down the road, provided all of this work can be grounded at the community level, policy makers who rely on data will have to be involved if systemic and structural change is the goal. Cities are rapidly moving toward data analytics to see their challenges more clearly, to draw connections between disparate data, and to engineer solutions. If such solutions fail to take into account the human stories and sociocultural factors made tangible through the arts, and if everyday residents of the city are not involved in cocreating such knowledge, efforts will fail, as they have so many times before.

Our planning of the second phase of AoT involves offering workshops in which community members will be supported in gathering and making artifacts of community interest, creating stories, and using photography, film, and geomapping to document community assets. Users will be involved in thinking about how the software works, what they would like it to do, and how they can imagine using it with friends and colleagues. There are existing capacities of the software we have yet to explore in our work with communities. MapTu allows users to import any 3-D objects built with computer graphic software, or scanned from actual objects using photogrammetry or laser scanning. These processes will facilitate representing thoughts and ideas with more imaginative forms than has been the case until now. The next version of the software will make it easier to get media into the AoT space as well, using tools such as smartphones and digital cameras without having first to upload it to another hosting venue, such as Vimeo. MapTu will be released as an open-source software project, allowing anyone to add functionality they want, if they have access to the programming expertise required.

However, AoT, like any media project, is a hybrid of technologies and cultural practices, and though in our technology-obsessed culture it might not seem like it, the technology is the easy part. The main challenges we ran into during the first phase of the project were not technological; they were about how the values and practices we bring to organizing are manifest in the media we create. We've used Wikipedia as a model of successful, open, crowd-sourced knowledge creation, but Wikipedia has rules, editors, and an administrative level that changes or deletes contributions deemed unworthy or untrue. The result has been a high degree of credibility for an encyclopedia. But the provenance of the encyclopedia enterprise is not that of media, particularly public media, or that of organizing. Consequently, how might successful organizing and media practices emerge together? Or more precisely, how can software development and organizing practices emerge and be modeled by and for all participants? How might democratic practices and openness flourish in the space of a particular software and its related organizing? Elliot E. Maxwell advises public and private sector clients on strategic issues involving the intersection of business, technology, and public policy in the internet. In his opinion, there are two extremes, open anarchy and rigid control. Both fail. The former produces a "yard sale" of disorganized uncredible information; the latter loses credibility because it is considered exclusive, siloed, and consequently, biased (E. E. Maxwell, unpublished data, March 12, 2015). While the challenge of deciding where on that spectrum AoT should fall can seem almost insurmountable, all media has done it for better or worse. The practices of journalism had to emerge over time, as did those of social media. The question is how to create the conditions to assure that Baltimore's residents have “transformative access” (Banks 2005) to MapTu—even at its earliest stages of development—and become the reason useful practices emerge. Banks writes, "More than mere artifacts, technologies are the spaces and processes that determine whether any group of people is able to tell its own stories on its own terms, whether people are able to agitate and advocate for policies that advance their interests, and whether that group of people has any hope of enjoying social, political, and economic relations" (2005, 10).

Like so many cities, Baltimore's social entrepreneurs and artists compete with one another for scarce resources—a system intentionally designed to promote competition and prevent cooperation. Yet, at the Chesapeake Arts Center event, we saw that AoT had the ability, as implied by its very look, to connect existing efforts together. It connected community- and university-based projects (Workers United, Baltimore Traces, and the Choice Program). AoT is a human networking project—more about connecting than creating out of whole cloth. There is a corollary in the intricate and organic mesh of street-level assets that journalist, author, and activist Jane Jacobs considered to be the real source of a city's ability to thrive, as opposed to the grandiose method of razing and building used by developer-mogul Robert Moses (Jacobs 1961). Jonathan Rose, in his recent book, The Well-Tempered City, echoes this need to integrate communities and systems of a city to address their volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity, known as VUCA (Rose 2016).

Our experiences made clear to us that public media technologies and practices to help people do what has not been done in Baltimore in the past, will not be merely a tool of organizing; they will be organizing—embodying, most importantly, the values of the organizers. Where we'd struggled, we'd forgotten the dangers of "inviting ourselves to the party." We were reminded in each encounter of the vulnerabilities of communities and individuals in going public with their stories, worries, or dreams. We relearned, as we will again and again, the value of beginning and staying in relationships with each other. We learned about holding spaces sacred for mutual respect and deep and radical listening. In the early days of preparing to host the IA conference, we came to understand the need for significant time and caring in order to engage in difficult dialogues, and we saw the fundamental importance of a commitment to compassion and empathy.

Our hopes and commitments for the next phases of this project are many. While the AoT space in the MapTu software at times seemed almost ancillary to the first phase of the project and all of its cultural organizing, perhaps that's what it should remain. If the larger issues of representation and participation are emphasized in the practice of AoT, we will develop the guiding principles and practices that should be followed as the project's online engagement increases. We are defining our commitments as grounded in Restorative Practices (no one speaks for another’s experience and we each speak to what we need to heal), the Virtues Project (we listen deeply to each other’s stories and create sacred spaces of safety and courage in which we celebrate each other’s humanity), Critical Participatory Action Research (our inquiries must be collaborative at all stages and focus on historical and contemporary inequities of power in order to contribute to social justice change), and the US Department of Arts and Culture (we will highlight the centrality of culture and human stories to all community organizing). We know that these values must be implicit and explicit, manifest even in the design of the software itself.

At the Arch Social Club event someone asked a question that went right to the heart of AoT’s fundamental goal. “But how does the map help us change anything?” We hope that what is beginning to differentiate AoT is not only its integration of cultural organizing and public media, but the ways in which it is paving the way for meaningful impacts. In addition to the longer-term goal of integrating data and engaging public officials, we are committed that AoT will design ways to measure tangible improvements in people's lives, and assess its value accordingly. We are committed to answering that question: How can the arts and humanities make a real difference? This is a very significant undertaking because individual and collective behaviors are difficult to link to specific cultural interventions. Cultural shifts in attitude or aesthetics must manifest into behaviors to be measured, and can easily become distorted in the process. In short, we cannot directly read the collective mind. AoT is already a deeply interdisciplinary undertaking, and it will need to become more so in order to address these challenges.

That said, we are taking time to acknowledge the positive initial impacts the work has had on relationships, on who is showing up and speaking up, on the cohesion and strength of an expanding team, and on more sustained conversations in communities on and beyond campus. The challenge now for AoT is to develop the project so that one day soon people will have heard the stories it offers, can point to its community histories, perspectives, assets, and bold plans for democratic change toward a more equitable city. Thomas King (2008) writes that a story is a gift, and he reminds us of our ethical responsibilities to stories and storytellers. “Just don’t say in the years to come that you would have lived your life differently if only you had heard this story. You’ve heard it now.”

Work Cited

Banks, Adam J. 2005. Race, Rhetoric, and Technology: Searching for Higher Ground. New York: Routledge.

Bimber, Bruce. 2012. "Digital Media and Citizenship." In The SAGE Handbook of Political Communication, edited by Holli A. Semetko and Margaret Scammell, 115–127. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Cammarota, Julio. 2008. "The Cultural Organizing of Youth Ethnographers: Formalizing a Praxis-Based Pedagogy." Anthropology & Education Quarterly 39 (1): 45–58.

Garrett, R. Kelly. 2009. "Echo Chambers Online?: Politically Motivated Selective Exposure among Internet News Users." Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 14 (2): 265–285.

IA (Imagining America). 2017. “History.” Imagining America. http://imaginingamerica.org/about/.

Jacobs, Jane. 1961. The Death and Life of Great American Great Cities. New York: Vintage Books.

King, Nicole P. 2014. “Preserving Places, Making Spaces in Baltimore: Seeing the Connections of Research, Teaching, and Service as Justice.” Journal of Urban History 40 (3): 425–449.

King, Thomas. 2008. The Truth About Stories: A Native Narrative. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Krieger, Nancy, David R. Williams, and Nancy E. Moss. 1997. “Measuring Social Class in US Public Health Research: Concepts, Methodologies, and Guidelines.” Annual Review of Public Health 18 (1): 341–378.

Rose, Jonathan F. P. 2016. The Well-Tempered City: What Modern Science, Ancient Civilizations, and Human Nature Teach Us About the Future of Urban Life. New York: Harper Wave.

Swift, Art. 2016. “Americans' Trust in Mass Media Sinks to New Low.” Gallup News, September 14. http://news.gallup.com/poll/195542/americans-trust-mass-media-sinks-new-low.aspx.

USDAC (U.S. Department of Arts and Culture). n.d. “Who We Are.” U.S. Department of Arts and Culture. Accessed February 18, 2017. https://usdac.us/about/.

Williams, Timothy. 2015. “Garbage Incinerators Make Comeback Kindling Both Garbage and Debate.” New York Times, January 10. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/01/11/us/garbage-incinerators-make-comeback-kindling-both-garbage-and-debate.html?_r=1.