Meet the Manuscript

Abstract

In a typical medieval history class, undergraduate students will access their source material through versions that have been translated, edited, annotated, and usually presented in a modern-day compendium source book. The original source material, however, is anything but accessible. This project was designed to get students engaged with original source material in order to ask and answer larger questions about the production and transmission of knowledge. Who produces knowledge? How is it disseminated? Who has access? These same questions are under scrutiny today as we transform from a print culture into a digital culture. Meet the Manuscript is a medieval manuscript crowdsourcing transcription/translation project involving both graduate and high school students. Through engagement with the original sources and digital surrogates, the students began using their imagination to try and inhabit the past, whether as the people in the will, paper makers, scribes, interpreters, or comparativists.In a typical medieval history class, undergraduate students will access their source material through versions that have been translated, edited, annotated, and usually presented in a modern-day compendium source book. The original source material, however, is anything but accessible. Many medieval documents are in languages other than English and most are written in a script that requires specialized study to decipher. It is no wonder these students feel somewhat alienated from and indifferent to the past. Getting original documents into the hands of both high schoolers and college students is a first step to breaking down these barriers, demonstrating firsthand that actively engaging with original source material can deeply connect us to other times, people, and cultures.

Today's advances in digitization techniques mean that just about anyone with an internet connection can view images of medieval manuscripts online. But little has been done to curate these collections of images for nonspecialists, and communicate the value of understanding these documents within their historical context. This project was designed to get students engaged with original source material in order to ask and answer larger questions about the production and transmission of knowledge. Who produces knowledge? How is it disseminated? Who has access? These same questions are under scrutiny today as we transform from a print culture into a digital culture.

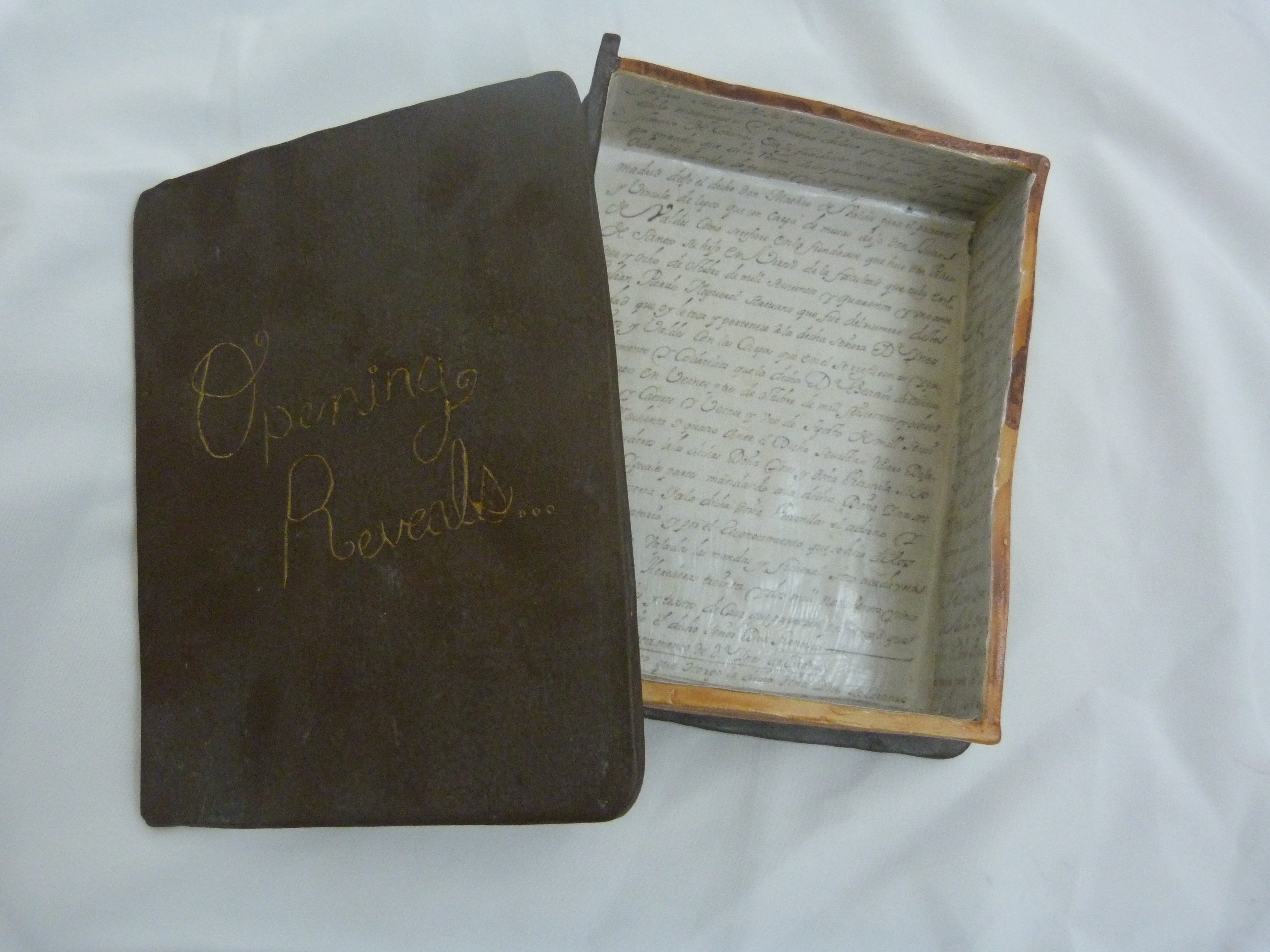

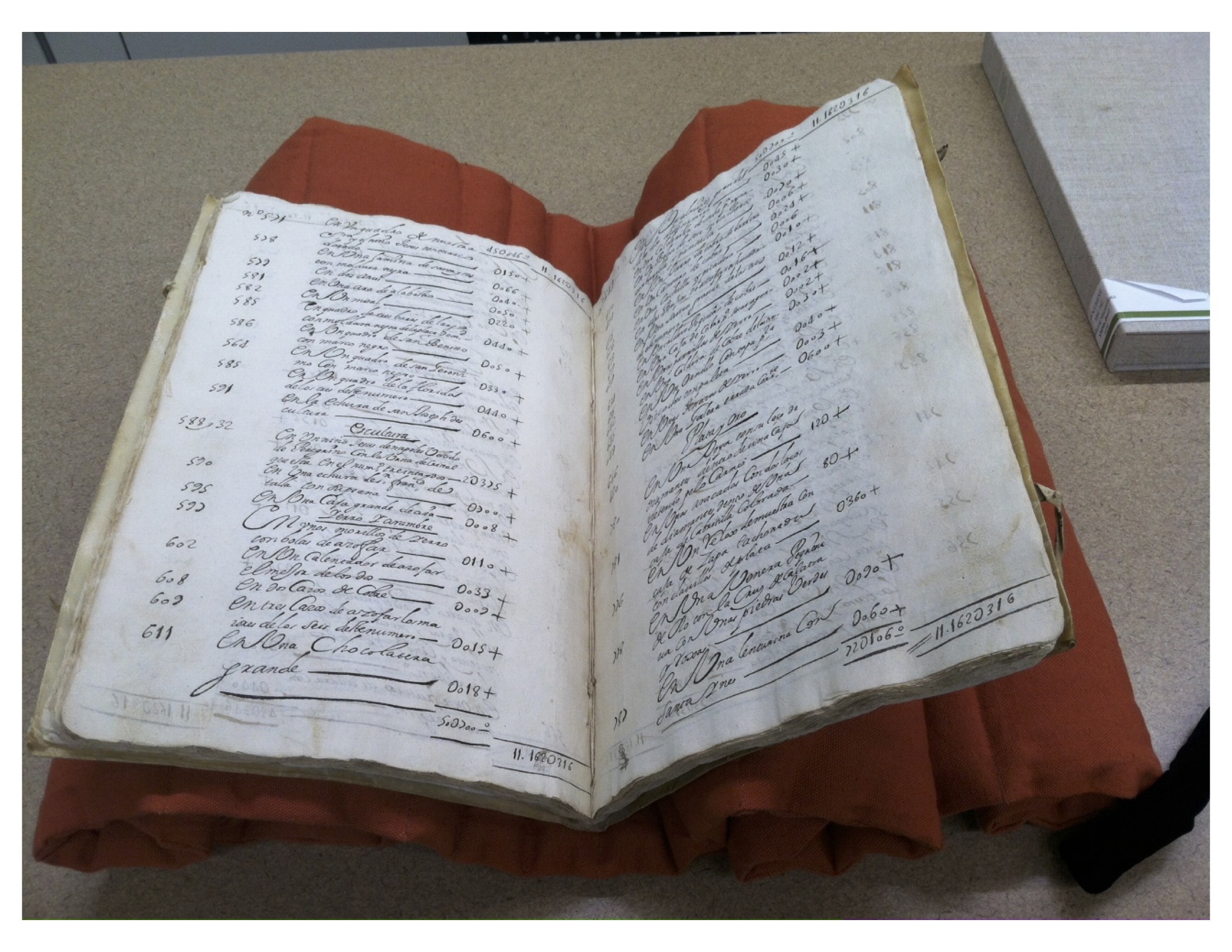

The subject of this project was a Spanish will from 1699 held in the University of Iowa Special Collections Library. In 1687, Don Francisco Muñoz de Carillo died. His daughter Ynes, Marquésa de Villel, followed him nine years later in 1696. In 1699, a notary from Cuenca, Spain, drew up a 192-page document that recorded the distribution of both the father's and daughter's wealth. Items included, among others, 28 beaver fur hats, six panels of tapestries, wool from Flanders, silks, cloths, linens, furniture, paintings, sculptures, gold, silver, and all manner of carriages.

The Meet the Manuscript project involved two principal components. First, there was a two-week workshop for University of Iowa graduate students, who worked on transcribing, translating, and TEI encoding the 1699 will. Also built into this workshop was the opportunity for the graduate students to learn firsthand how the document was made—by making their own facsimile. Thanks to the University of Iowa Center for the Book, sessions with papermaker Tim Barrett, book binder Melissa Moreton, and calligrapher Cheryl Jacobsen helped students to create their own handmade paper, which soon sported their own examples of italic script. They then bound the pages together in a tacketed binding with alum-tawed laces and case paper (which substituted the parchment cover of the original 1699 will).

Second, three area high school classes participated by using the project to further their own academic goals. Norwalk High School (Norwalk, IA) students from pottery, metalsmithing, and 3-D design classes created works inspired by their visit to the University of Iowa Special Collections Library, where they perused and explored the 1699 Spanish will and other manuscripts from the collection. The students were tasked with considering the question, "What makes a book a book?" They then went back to their respective high school classrooms to express their answers through art.

Students from the Spanish AP class at Central Academy in Des Moines, IA, used digital image surrogates of the 1699 will to create their own group projects. They were able to capitalize on individual strengths and interests in the design and execution of their projects. One group focused on creating a key for decoding the script found in the manuscript, while another made a glossary of terms. Members of a third group decided to write Don Francisco's obituary in Spanish, creating a life for him based upon parts of his will.

Students from an AP World History class at Kennedy High School in Cedar Rapids, IA, also undertook research projects based on the 1699 will. Each day newly translated pages were sent to Kennedy High School. From these digitized pages, students developed their own research questions and methods for answering them. One student looked at why wills even exist, and decided to explore how a seventeenth-century will might compare to a will today. Another conducted research into the factors that may have figured into the survival of the centuries-old manuscript.

At all stages, both graduate students and high school students were able to integrate resources using the original document, digital surrogates, and the pedagogy of action-based research. Because students were actively producing knowledge, context, art, and thought experiments with and in response to this distant document, they formed a relationship to the past. Through engagement with the objects—even digital objects—they began using their imagination to try and inhabit the past, whether as the people in the will, papermakers, scribes, interpreters, or comparativists. One student’s reflection seems to sum it up: "Working with this project made me more motivated since I could see an actual application for our project with the University of Iowa and a clear demonstration of practicality. I really liked seeing something that was written for a purpose other than to teach Spanish, and I liked the process of translating foreign writing styles into modern Spanish. I was definitely more involved and committed to this project than to any other we have done this year."

Many thanks to Greg Prickman, Colleen Theisen, and Margaret Gamm at the University of Iowa Special Collections Library for their help in making the manuscript available and accessible, as well as hosting the students from Norwalk High School.