Mapping Islamophopia

Abstract

Mapping Islamophobia is a publicly-facing digital project that uses data visualization to present information concerning anti-Muslim hate and its effects in American public life. We draw on original datasets to populate two series of interactive maps. The first set of maps, dedicated to instances of Islamophobic activity, create an impression for the user of the conditions of public life for American Muslims. The second demonstrates how American Muslim communities have responded to the presence of Islamophobia in public life. By illustrating the extent of Islamophobic activity in the United States and the remarkable community outreach efforts through which American Muslims work to humanize themselves and Islam in the eyes of the broader public, Mapping Islamophobia raises significant questions about how anti-Muslim hate affects the nature of American Muslim participation in public life.With Grinnell College students Julia Schafer, Farah Omer, Haseeb Haroon, Sydney Banach, Thomas Aldrich, and Chloe Briney; and Grinnell College Digital Technology Specialist Mike Connor

Supported by Grinnell College, Mellon Foundation (Digital Bridges: University of Iowa and Grinnell College)

A central feature of American “freedom mythology” is that participation in public life is free and voluntary: We choose how and when to be an active participant in our local and national communities. Yet the notable increase in hate incidents, hate crimes, and hate speech in the United States reminds us that many Americans cannot set their terms of participation in the same manner others take for granted. Our project, Mapping Islamophobia, uses data visualization to explore how anti-Muslim hate affects American Muslim participation in public life. We hope that our project serves as a tool and information source for the public, educators, students, researchers, and policymakers.

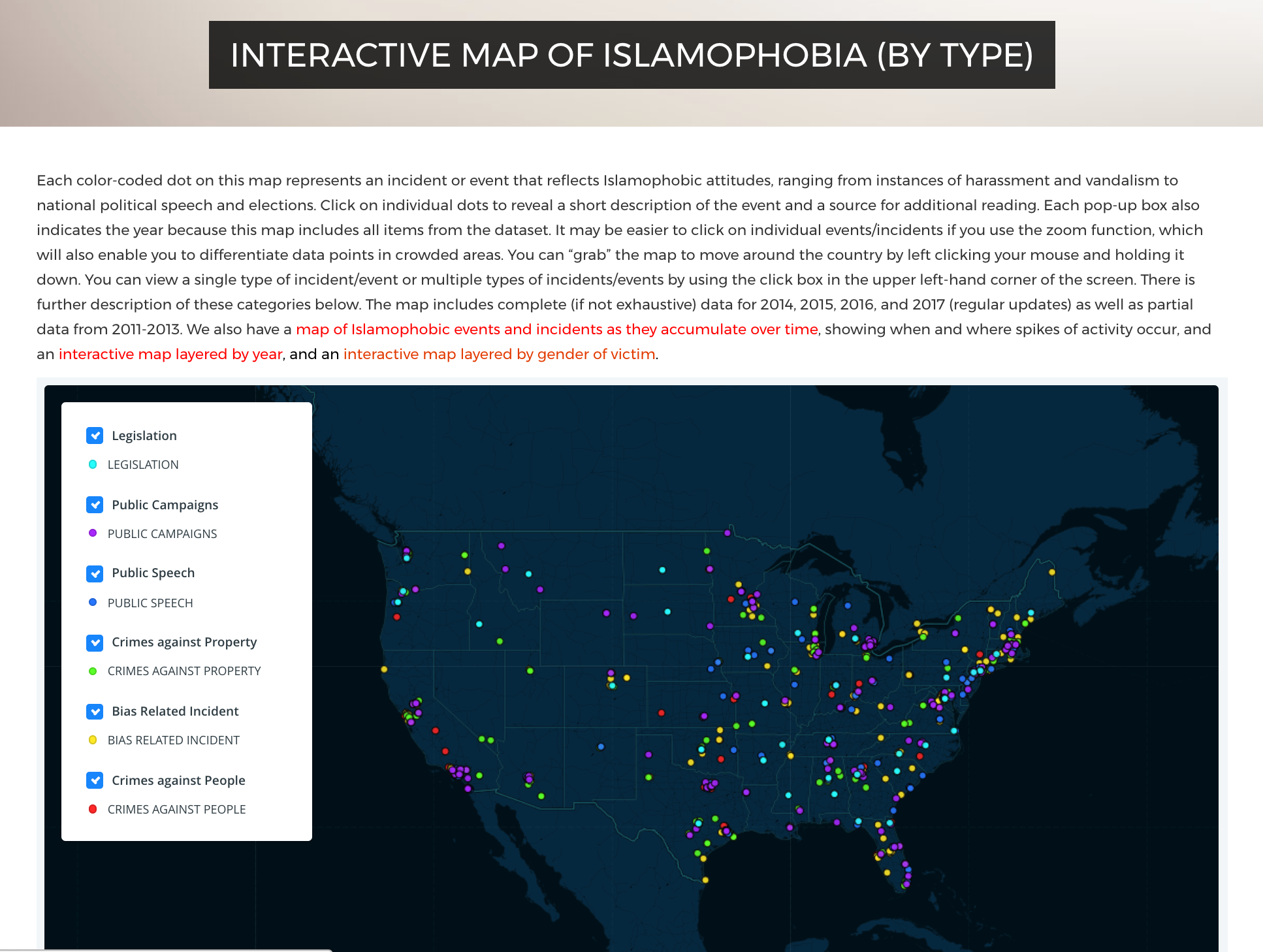

Our website addresses a number of problems relating to anti-Muslim hate and its effects. First, there are no reliable statistics documenting anti-Muslim activity. The FBI collects information on hate crimes, but participation by local law enforcement agencies is voluntary. Furthermore, many expressions of anti-Muslim hate are not crimes. Verbal harassment, public campaigns and rallies by anti-Muslim groups, anti-Muslim political speech, anti-shari'a legislation—these, too, are manifestations of hate that affect the conditions of public life for American Muslims. To address this problem, we have built a dataset containing information on a wide variety of anti-Muslim activity that we use to populate our maps on Islamophobia.

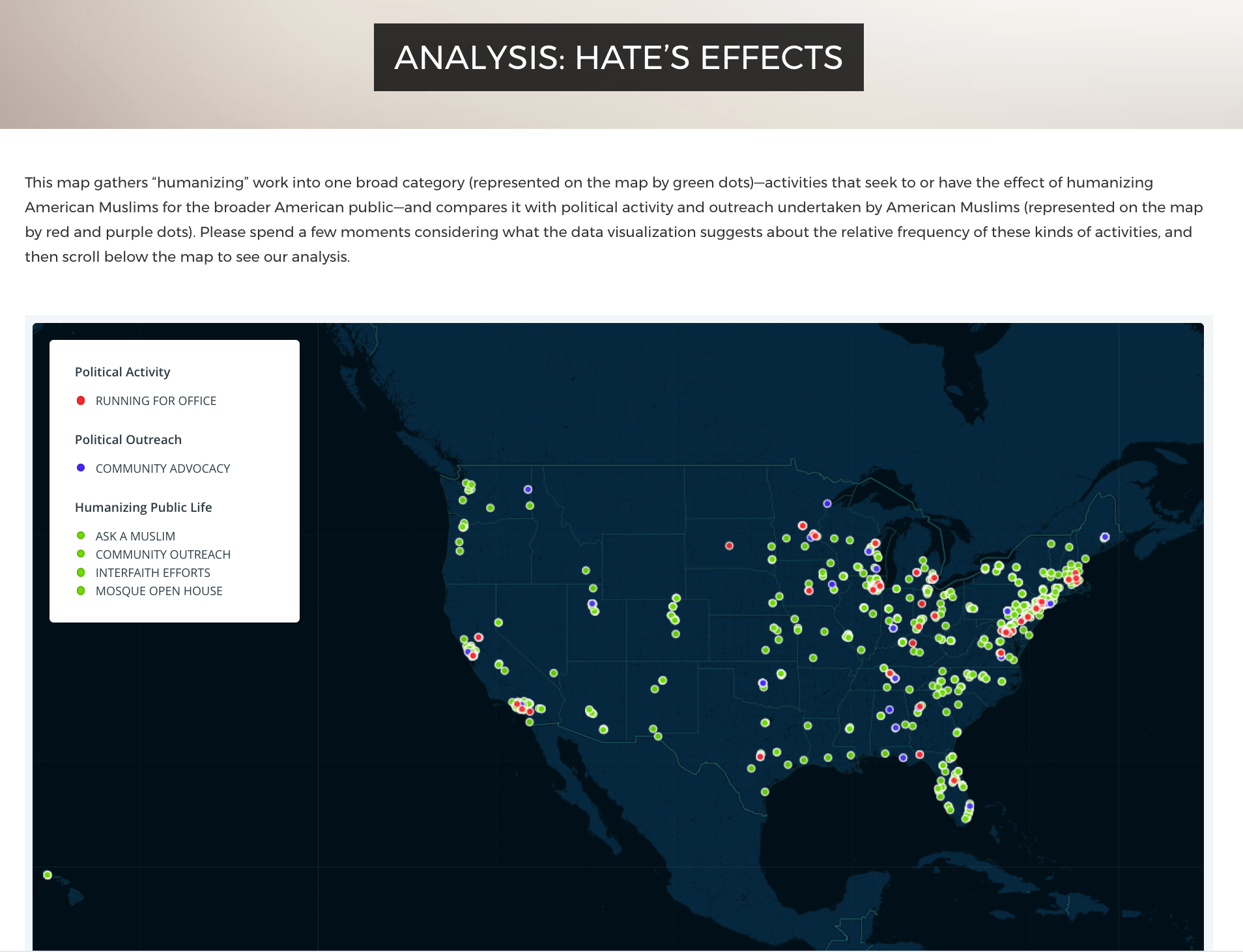

The second problem we address is the common perception that anti-Muslim hate results, at least in part, from a lack of American Muslim participation in public life. Skeptical of this claim from the outset, we have been building a second dataset tracking what we call “humanizing work” of American Muslims — community outreach efforts and interfaith initiatives, for example. This data challenges misperceptions and points to how fear and the burden of responding to hate may be affecting the nature of American Muslim public participation. This dataset also includes instances of political outreach and political activity, which when set beside data on “humanizing work” raises questions around free and voluntary participation in public life. We use this dataset to populate a series of maps called “Countering Islamophobia.”

We draw data for the project from reputable news sources, making a conscious decision against crowdsourcing. This means that our database is not exhaustive. But it certainly allows us to capture and represent trends and gives us confidence that our data is strong. We currently include data from 2017 through 2010 on our web site. Our goal is to eventually include data back to 2001.

The third problem Mapping Islamophobia addresses relates to representation. How is it possible to communicate something abstract like the “conditions of public life” for American Muslims? We begin with the premise that statistics alone are insufficient to tell the story of anti-Muslim hate and its effects. Our interactive maps create impressions on an emotional register and present concrete information about trends in Islamophobia over time and geography, the way that hate and gender intersect, and the relationship between public hate and American Muslim participation in public life. Together, we hope they prompt users to consider how they imagine America.