Abstract

Celebrating Simms: The Story of the Lucy F. Simms School project represents a yearlong partnership between a predominantly white academic institution (James Madison University) and a predominantly black neighborhood in Harrisonburg, Virginia. The project’s goal was to preserve local African American memories linked to the site of Harrisonburg’s former all-black school, and to transform them into a permanent exhibit that could be mounted on the former school’s walls and online. The authors chart the journey of this project, exploring how predominantly white institutions in rural locations face significant barriers in undertaking projects such as this because of the deeply entrenched distrust with which they are often viewed by surrounding, marginalized communities. The authors respond to this issue by discussing a second phase of the project, Simms 2.0, which focuses on the development of digitally enabled archives to open up possibilities for preserving rural African American and other minority archives.This study has been sanctioned by James Madison University's Office for Research Integrity under the study "Representing Black Harrisonburg," Protocol ID: 16-0557. All images and other media contained herein have been previously published adhering to the guidelines of this protocol, and all media can be found on the publicly available website for the project.

The Single Story

In a 2009 TED talk, novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie spoke of the “danger of the single story.” As she put it, when you “show a people as one thing, as only one thing, over and over again . . . that is what they become.” Adichie continued, “It is impossible to talk about the single story without talking about power” because “how [these stories] are told, who tells them, when they’re told, how many stories are told, are really dependent on power. Power,” she argued, “is the ability not just to tell the story of another person, but to make it the definitive story of that person” (Adichie 2009). Although Adichie was talking about the production of literature, her observations are equally relevant to the production of academic research. As Linda Tuhiwai Smith argues in Decolonizing Methodologies, “from the vantage point of the colonized, . . . the term ‘research’ is inextricably linked to European imperialism and colonialism.” For colonized peoples, Smith continues, “research” recalls how “Western researchers and intellectuals” have presumed “to know all that it is possible to know of us, on the basis of brief encounters with some of us.” It recalls how “the West can desire, extract and claim ownership of . . . the things we create and produce, and then simultaneously reject the people who created and developed those ideas” (L.T. Smith 1999, 1).1 Thus, although academics often think of their research as a benevolent enterprise devoted to the greater good, for many minority and colonized populations it has long associations with the exploitative, paternalistic, and homogenizing logic that Adichie described as the logic of the single story.

Over the past 20 years, community-engaged scholarship practices have fought against the dangers of the single story not only by encouraging academics to tell new stories—stories of the people rather than stories of the powerful—but also by inviting nonacademic storytellers into more collaborative and reciprocal relationships in the production and reception of academic knowledge (Miller, Wheeler, and White 2011). As Smith (L.T. Smith 1999) argues, the production and affirmation of such “counter-stories” can provide “powerful forms of resistance” (2); decolonial theorists often argue that “alternative histories” and “alternative knowledges” (34) are therefore a “critical and essential aspect of decolonization” (30).2 However, despite community-engaged scholars’ efforts to disassociate from power-imbalanced research models and negotiate reciprocal community partnerships, these efforts are often hindered by the continued perception and often the reality of academic partners as the “authority” when it comes to the acquisition of funding, the instruction of students, the legitimation of research methods, and the production and dissemination of knowledge. These concerns about power imbalances in community-university partnerships are especially prevalent when historically empowered institutions try to partner with historically disempowered community partners, as is so often the case. As a result, even within community-based projects, partnerships often remain fraught by both real and perceived power imbalances, and thus require the constant negotiation of control and outcomes in relation to the physical material, the process, and the end product: the story.

In what follows, we present a recent community-engaged historical recovery and archival preservation project to explore some of the challenges and successes of creating stories for and with historically disempowered communities. Celebrating Simms: The Story of The Lucy F. Simms School is a large, permanent exhibition, website, and companion booklet that celebrates the history and role of education among the African American community in Harrisonburg, Virginia. Several community members had previously researched and written on the topic, and there was a strong desire within the community to see this work celebrated, expanded upon, and given a visible and accessible place in the wider Harrisonburg community. Celebrating Simms aimed to give voice to and build upon this work, foregrounding local African American voices and needs in both the design of the project and the shape and placement of the exhibit’s narrative. In this effort, the project aligned with the methodology of the counter-story by privileging nonacademic voices to tell their own story rather than imposing one upon them. However, the project also raised important considerations about the practical difficulties of building trust between predominantly white institutions and historically black communities, and the relationship between this process of trust-building and the kinds of stories we tell together. For while the production of the exhibit’s narrative was a necessary first step in building trust between our institution and our community partners, it drew us into the complicated and affective politics of the single story—the fear that we could not be trusted to take part in that storytelling, and the reality that telling one story, even when it is a counter-story, always means leaving other stories out.

We begin this essay by presenting a timeline and general overview of the design and completion of the Celebrating Simms exhibition. Noting the project’s significant successes, we follow with an analysis of how our university-community partnership faced and solved the challenges of building trust and sharing authority while also collaboratively writing and designing the historical narrative that would ground the exhibit. To conclude, we sketch a proposed second phase of the project that responds to the concerns about shared authority and shared storytelling that were raised by the first iteration. Tentatively titled Simms 2.0, it harnesses the power of digital networks and publishing tools to produce “participatory archives” that allow for a more widely shared form of history collection and storytelling than the physical exhibit and its digital and print iterations could possibly allow. Yet, we argue this method complements and informs the initial stage of the project rather than replaces or corrects it. A solid architecture for projects such as Celebrating Simms is ultimately determined not just by the use of a specific medium or narrative technique, but by a solid basis of trust among the collaborators, a keen attention to how institutional power is summoned and deployed, and an openness to the perpetual making and unmaking of stories.

Celebrating Simms: Background and Development

In recent years, numerous archival preservation projects related to African American history have taken place in big cities like New York, Chicago, Baltimore, Miami, or Washington, D.C., all home to strong, historically black institutions that have been devoted to documenting African American life, culture, and history for almost a century.3 Nevertheless, the location of these institutions presents some limits on the kinds of stories that can be preserved, favoring urban and nationally significant ones at the expense of rural and locally significant ones (Filene 2015; Caswell, Harter, and Jules 2017). Predominantly white institutions in rural locations have the potential to fill this gap, to leverage their institutional power in order to help preserve local African American histories, voices, and archival materials; with the rising profile of engaged learning practices and diversity initiatives at many universities, such institutions also have increasing interest in this goal (Cantor and Lavine 2006; Jay 2010). However, these institutions face significant barriers in fulfilling that goal because of the deep skepticism with which they are often viewed by surrounding, marginalized communities (L.T. Smith 1999, 3; Stevens, Flinn, and Shepherd 2010). In many cases, the very presence of predominantly white institutional power can foreclose upon the possibility of true partnership before it begins, and thus shut down plausible avenues of local historical preservation and production.

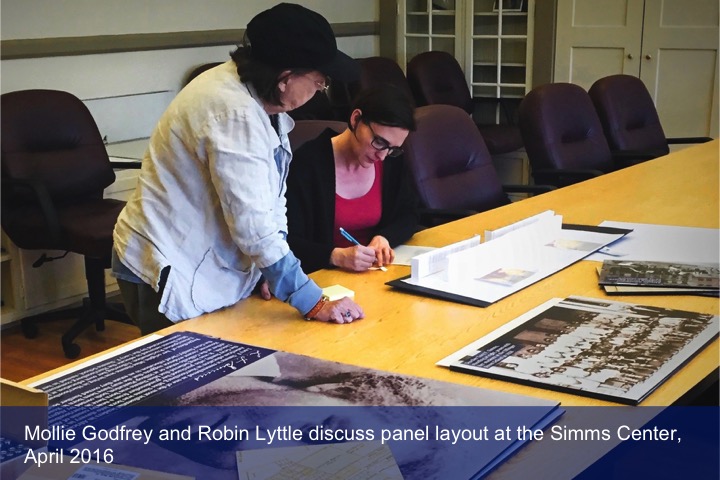

Celebrating Simms: The Story of the Lucy F. Simms School comprises a permanent exhibit, website, and companion booklet created as the result of a yearlong partnership between a predominantly white academic institution and the largely African American neighborhood within a mile of the campus gates in Harrisonburg, Virginia. As two white professors in the English and Writing, Rhetoric and Technical Communication departments at James Madison University (JMU), we began by partnering with local activist Robin Lyttle, founder of the Shenandoah Valley Black Heritage Project; Billo Harper, a designer, curator, and producer who grew up in the neighborhood and had produced a documentary on the school; and Dr. David Ehrenpreis, the director of our university’s Institute for Visual Studies, which hosted the classroom-based portion of the project. Through the course of the year and a half that we spent on this project, from January 2015 through August 2016, we formed partnerships with 75 local individuals and institutions, including an advisory board of Simms alumni; other JMU professors and staff; nearby Eastern Mennonite University and Bridgewater College professors and staff; librarians, local historians, and archivists associated with the Harrisonburg-Rockingham Historical Society and Massanutten Regional Library; 16 undergraduate students; an undergraduate multimedia consultant; one graduate assistant; three high school teachers; and a broad range of former and current Harrisonburg residents.

Our goal, as a collaborative team, was to preserve local African American memories linked to the site of Harrisonburg’s former all-black school, located in what was once a predominantly black neighborhood in the northeast of Harrisonburg. The Lucy F. Simms School, named after a formerly enslaved woman and famed Harrisonburg educator, was built in 1938 to serve African American students from all over Rockingham County and the Shenandoah Valley. The school served such a large area because, as anthropologist Laura Zarrugh explains, “the African American population” of Rockingham County “has always been much smaller than in the rest of Virginia and the South. For example, in the 1840s, slaves comprised 11 per cent of the population of Rockingham County compared to 57 per cent of the population of the four adjacent counties east of the Blue Ridge Mountains” (Zarrugh 2008, 23). Racial relations in Harrisonburg have also been described as less hostile than in other parts of Virginia—at least when compared to nearby segregation-era “sundown towns,” which banned African Americans after sunset, or to Prince Edward County further south, where white opposition to integration was so intense that they shut down the public school system for five years rather than integrate the schools (Loewen 2006; Green 2016). In contrast, when integration came to Harrisonburg in 1965, the conflicts were quieter: the Lucy F. Simms School was closed over the objections of many black students and alumni, many of the school’s black teachers lost their jobs, and many black residents felt that an important center of community life had been lost.4 In 2005, the building of the former Simms school reopened as a community center, and former Simms students were finally able to use the space again for computer access, meetings, and community events, even though little visible trace of the school they had known remained. In many ways, the various factors that made Harrisonburg less racially volatile than other parts of the segregated south also made black experiences less visible to the wider Harrisonburg community, enabling the greater marginalization of local black history.

Prior to our project, several community members had already begun to reclaim the history of the Simms building and the history of African American education in the area by self-publishing their own research and memories about the school and the community it served, and raising funds to hang a couple of framed photographs in the entrance of the Simms Center.5 However, much of the school’s history, and the archives that could support it, were hidden from the public eye. The school’s records were lost in a fire, and astonishingly little that had been retained or remembered by former teachers or students had been donated to public archives. Moreover, what material did exist was not readily available to students at either the high school or university level, nor to former Simms students or the wider Harrisonburg community. Oral histories remained untranscribed, archives were scattered over multiple institutions, some of which had no publicly available finding aids, and several of which had accessibility issues due to either limited hours or limited parking options. With an aging population of former Simms students, and decades of distrust between that population and several of the predominantly white archives and academic institutions in the area, much of the remembered history and material related to the Simms school was at risk of being lost—a situation that is typical for many rural African American communities (Godfrey 2016, 166).

The Celebrating Simms project came into being with the goal of transforming what many community members described as a site of loss into a site of memory and celebration. Although Thomas Cauvin cautions against public histories that take the form of celebration because they can shut down contrary memories and experiences (2016, 219–221), our community partners felt strongly that celebration was the appropriate form for this exhibit to take. In fact, numerous members of our Simms advisory board described their vision for the exhibit’s narrative as running counter to mainstream myths about the inferiority of black schools in the segregated south (Walker 1996, 1). In contrast, many former Simms students were interested in celebrating the quality, creativity, and extracurricular robustness of their former school and its teachers, as well as bringing awareness to the loss that they and their community felt when their school and its support network went away. As historian Vanessa Siddle Walker argues, “although black schools were indeed commonly lacking in facilities and funding, some evidence suggests that the environment of the segregated school had affective traits, institutional policies, and community support that helped black children learn in spite of the neglect their schools received from white school boards” (1996, 3) . Critic bell hooks adds that, in her own experience, integration marked a “shift from beloved, all-black schools to white schools where black students were always seen as interlopers, as not really belonging” (hooks 1994, 4). Our project’s goal was to address some of these residual feelings within the community, and to use both Simms herself and the school named in her honor as focal points from which to commemorate not only the many people that made the school so beloved, but also the school’s place at the heart of the local community’s life.

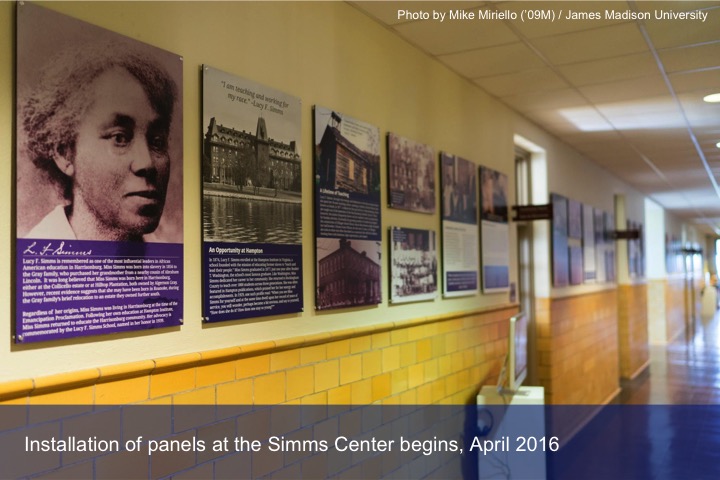

Initially, we had planned to use a one-semester research internship and a one-semester studio seminar to create an exhibit of 30 panels or so, to be temporarily housed in The Lucy F. Simms Center for Continuing Education in Harrisonburg. However, the interests of various community partners quickly led the project to grow in scope and ambition, from a small temporary exhibit to a large permanent one. Emboldened by this vision of permanent spatial transformation—of turning the bare walls of this former school into a memorial of the school’s history—community members became increasingly invested in sharing their time, memories, family photographs, and oversight with the project. The resulting exhibit, which was financially supported by a range of internal JMU grants, is made up of over 60 permanent, professionally printed panels, permanently installed on the school’s interior walls, spanning 150 years of history, and containing over 120 photographs.

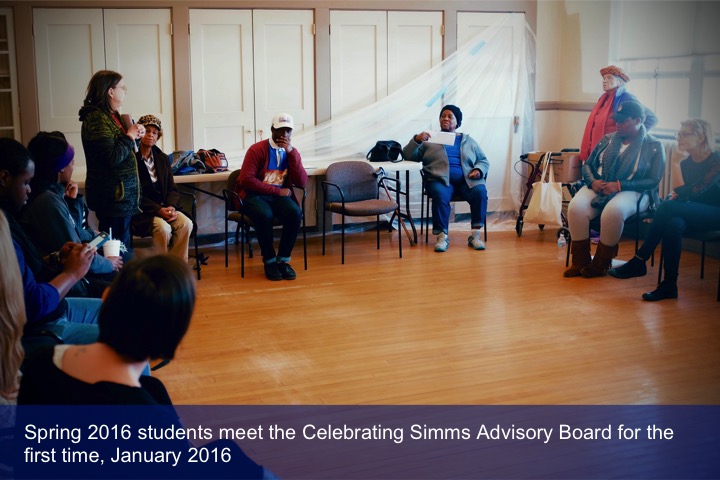

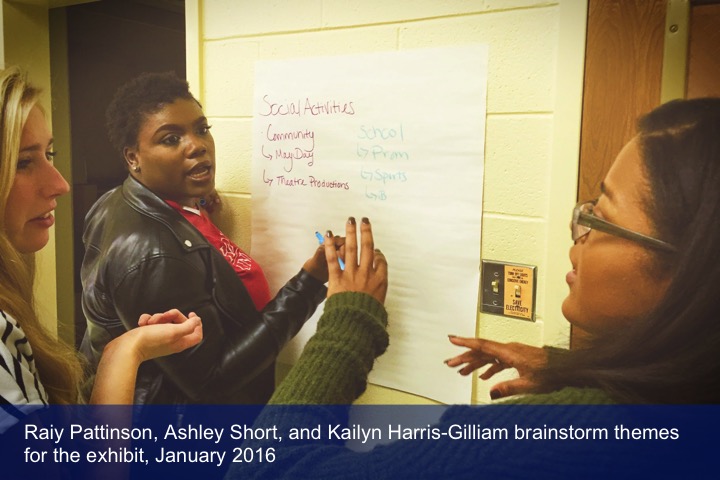

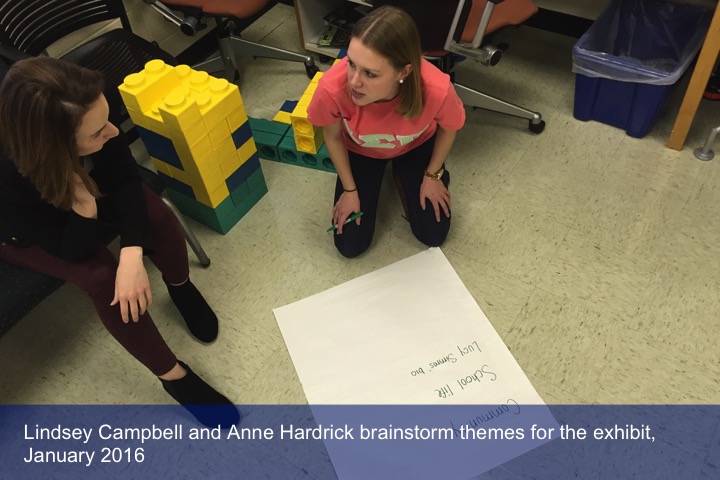

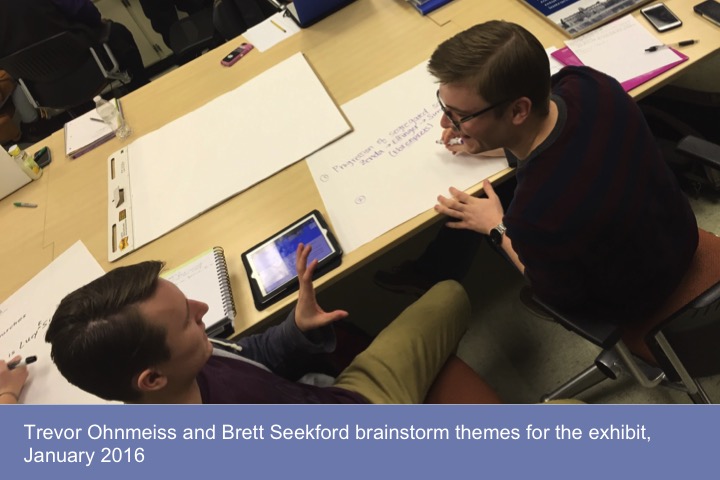

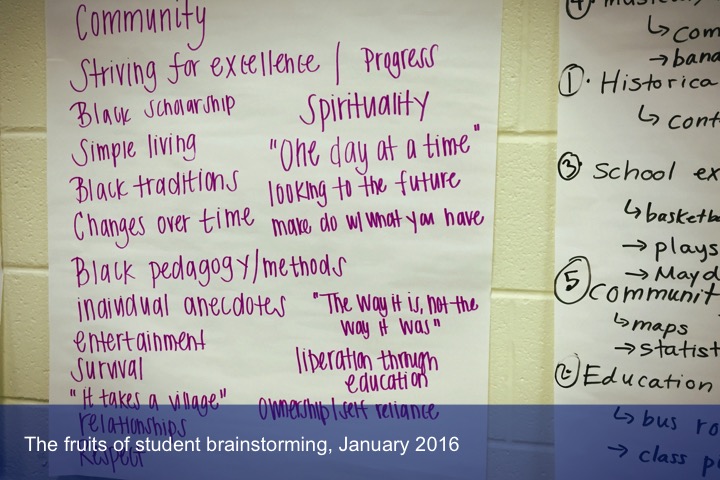

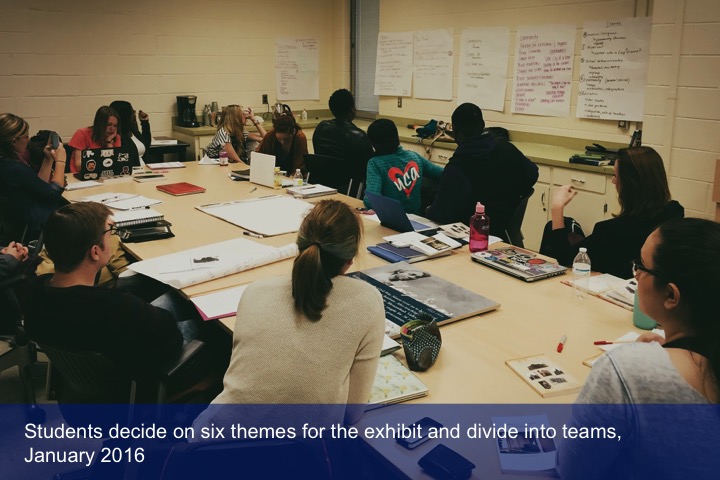

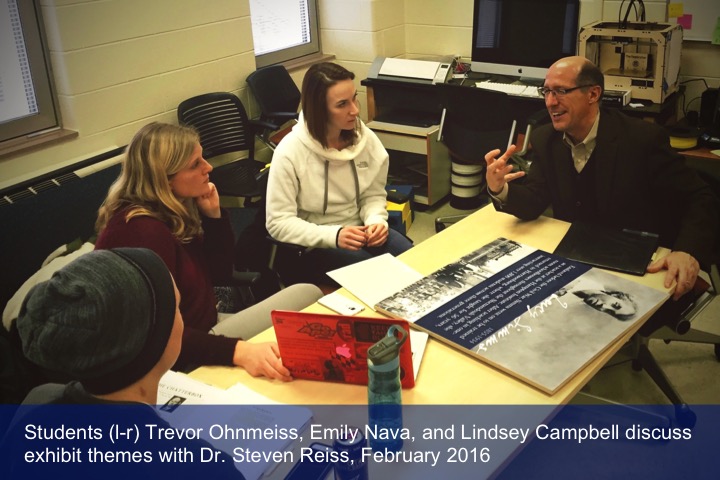

The composition of the exhibit was the result of a collaborative back-and-forth between students and community partners. Before they began work on the exhibit, several members of the Northeast neighborhood and former students of the Lucy F. Simms School met with our students to agree on goals for the project. Then, the students brainstormed possible themes for the exhibit and divided into six teams to tackle them: historical context; the life of Lucy F. Simms; the Lucy F. Simms School; extracurricular activities; life in the neighborhood; and the Simms legacy. They drafted narratives for each of these topics in consultation with local historians and professors, relying primarily on the material already available on Robin Lyttle’s website, in the few published resources on African American education and life in Harrisonburg, and in local archives such as the Heritage Museum. Presenting their drafts to our community partners revealed significant narrative gaps and topics that required reworking or refining. The design and narrative of the exhibition panels transformed dramatically over the course of a few weeks as the students worked intensely with community members to track down better images in private photo albums and tell a richer and more focused story, a process that resulted not only in a more successful exhibition but also in a greater sense of trust and camaraderie between the students and their off-campus collaborators.

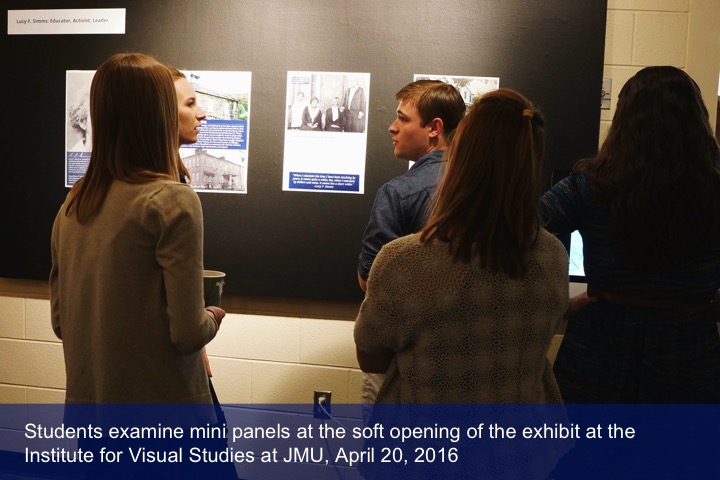

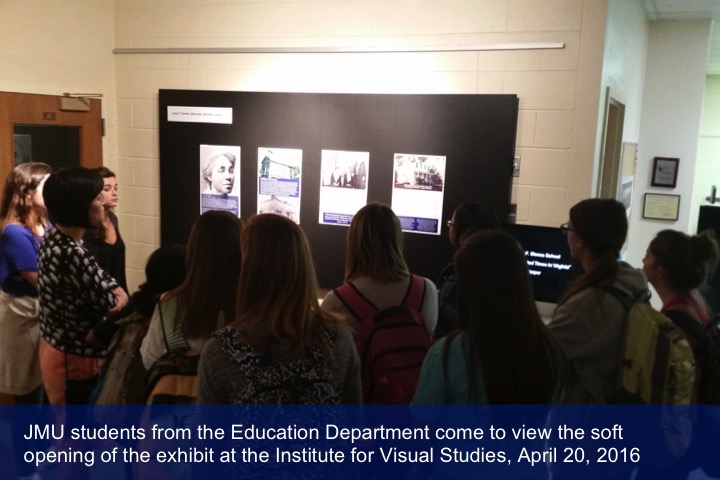

The permanent exhibit was unveiled on April 25, 2016, at the Simms Center, an event that attracted over 300 people, as well as the interest of the local and JMU media (Flynn 2016; Tucker 2016). It was also circulated in other forms: as a centerpiece for the Simms Reunion the following month; as 1,000 copies of a companion booklet, which attendees could take home with them; and as a smaller-scale exhibit installed in the local high school. Since then, a private benefactor put forward funding to have part of the exhibit replicated in each of the surrounding county’s four high schools. Our students also created a companion website which contains different ways for visitors to interact with the exhibit: they can interact with a slideshow of the exhibit panels that appear as they do on the walls of the Simms Center, or they can peruse a more interactive version of the exhibit and click on each image contained therein to look at information pertaining to each image, such as who is in the photograph, who owns the image, and its provenance. This is possible because the website is run on Omeka, a digital humanities initiative to create museum and online exhibits that reflect archival standards. The website also contains other interactive elements that remix elements of the exhibit, such as an interactive timeline and map, and provide further information, such as a page on the history of the project, clips from the documentary on the school made by project associate Billo Harper, and curricular materials designed by education majors in our class to allow K–12 Social Studies teachers to incorporate the exhibit into classroom lessons while fulfilling state assessment standards. We have since learned that the exhibition has also been the focus of several school trips from classes as diverse as engineering and creative writing classes at JMU to social studies classes from the local middle and high schools.

The success of the Celebrating Simms project suggests that local, predominantly white institutions can serve a powerful role in assisting with the recovery, preservation, and dissemination of local African American history. As historian Annette Gordon-Reed argued at a public summit on “Memory, Mourning, and Mobilization” at Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello estate in Virginia, when it comes to African American history, “The first thing you do . . . is you have to know things. You have to gather the material. You have to understand what actually happened” (2016). This process is the necessary first step in complicating the single story—in replacing dominant and colonizing narratives with what literary scholar Erica Edwards describes as “the arduous, undocumented efforts of ordinary women, men, and children to remake their social reality” (2012, xv). University researchers and universities have an important and necessary role to play in this process. As engaged scholar Ellen Cushman argues, “public intellectuals can use the privilege of their positions to forward the goals of both students and local community members” (1999, 330). They possess the power to deploy resources, disseminate knowledge, and, as Linda Tuhiwai Smith puts it, to “legitimate innovative, cutting edge approaches which can privilege community-based projects” (1999, 125). And yet, despite what might seem like the self-evident value of helping to preserve such stories in a public form—either on the walls of the former Simms school, online, or in a public archive—we encountered significant obstacles that we believe are related to the community-engaged scholar’s simultaneous and sometimes contradictory efforts to diminish and also deploy his or her own institutional power.

Building Trust: The Challenges of Shared Authority and Shared Storytelling

As Adichie reminds us, “How [stories] are told, who tells them, when they’re told, how many stories are told, are really dependent on power” (2009), and as we have seen, the stories told by academics, backed by the institutional power of the academy, are no different. In Harrisonburg, the history of the local African American community was almost entirely untold until relatively recently, and only in the past 20 years or so has it begun to be incorporated into local history exhibitions, commemorative sites, oral history projects, and school curricula as the result of both community-driven- and institutionally driven-projects. With the exception of several African American oral history projects (Getachew 2000; Metz 2005), the majority of these efforts have focused on either late-nineteenth-century life in the Shenandoah Valley—including such projects as the preservation of the Hamburg Regular School at the Luray Valley Museum, the preservation of Long’s Chapel in Zenda, and the incorporation of early, local African American history into the Rockingham County school curriculum—or exemplary historical figures, such as the mural commemorating Lucy F. Simms in downtown Harrisonburg and the opening of the Harriet Tubman Cultural Center in Harrisonburg. More recently, community members and scholars have begun to explore local African American community life in Harrisonburg, including projects on spatial history, property ownership, and the R4 project of the late 1950s and early 1960s, in which numerous African American homes in Harrisonburg were destroyed in the name of urban renewal (Borg et al. 2016; Bachman 2017; Ehrenpreis 2017).6 Such scholarship not only expands the focus on local history into the twentieth century, but it provides an important counter-narrative to the long-cherished story of Harrisonburg’s relative racial tolerance in relation to other southern communities.7

As we began work on our project, then, we found that many community members already had direct experience with both community-driven- and institutionally driven-research projects. We also found that they already had fears and concerns that arose both from those past experiences and from our own association with JMU. To begin with, we found that some of our community partners were wary of discussing painful aspects of the past with our students. For example, when one of our students asked our advisory board about segregation, our gregarious group became uncharacteristically quiet. As Thomas Cauvin has argued, we found it necessary to gauge and respond to community cues regarding how to handle histories of oppression, even though “silencing difficult aspects of the past is clearly not ideal” (2016, 219). We also found—through repeated conversations with a range of individuals—that many of our community partners were worried that our research would be about them rather than for them; that it would become inaccessible to them after the project ended; that it would distort or misrepresent their experience; or that it would address questions, concerns, and audiences that were not their own.

Drawing on best practices for community engagement, which encourage reciprocity as a means of addressing such sensitive terrain, our project began with the explicitly articulated and collaboratively developed goal of telling a story that was not only meaningfully shaped by the needs and interests of the local community, but would be presented in spaces accessible to and valuable to the community. As such, we were adapting two models described by Linda Tuhiwai Smith in Decolonizing Methodologies (originally proposed by Ma̅ori researcher Graham Hingangaroa Smith) for “culturally appropriate research . . . undertaken by non-indigenous researchers”—“a ‘power sharing model’ where researchers ‘seek the assistance of the community to meaningfully support the development of the research enterprise’” and “the ‘empowering outcomes model,’ which addresses the sorts of questions [indigenous] people want to know and which has beneficial outcomes” for them (L.T. Smith 1999; see also G.H. Smith 1992). In the field of public history, such models are typically discussed in terms of “shared authority,” which turns “people from mere consumers into active participants” (Cauvin 2016, 216) because, as Michael Frisch explains in “From a Shared Authority to the Digital Kitchen, and Back,” “the interpretive and meaning-making process is in fact shared by definition” (quoted in Cauvin 2016, 216; see also Frisch 2011). We believed that we could enact these power- and authority-sharing models by collaborating with community members on the design of both the project and the end product. We held multiple meetings with key collaborators as we designed the project and its process; arranged an advisory board of community members who agreed to meet with students at several stages in order to cocreate and peer review the story; created multiple opportunities for community members, local historians, and academic peers to review and make corrections to the exhibit panels; and ensured that the various products that we created were in valued spaces and forms.

However, despite our efforts to cultivate reciprocity and collaboration, our institutional power continually threatened this partnership, even though it was this power that also made the partnership possible. For example, our institutional power meant that we knew that we could secure funding to print the exhibit and sponsor the opening; we knew that we could get our library’s Special Collections to host and maintain the website; we knew that we could secure student participation as researchers; and we knew that we could secure the interest of high school teachers in integrating the exhibit into their curriculum. Nevertheless, the clear presence of our institutional power in these various ways simultaneously raised questions about ownership and trust. How could we convince our partners that our desire to preserve and publicize was not a desire to take or to control? How could we equitably manage the preservation and production of the images, the exhibit, the website, and the story? How could we do all of this within the confines of academic and institutional norms? Answering these questions required constant negotiation on several fronts beyond the widely agreed upon need for reciprocity.

To begin with, we found that the institutional process of negotiating reciprocal relationships with community partners ironically held the potential to derail our project before it began. The IRB process was developed to protect the rights of research participants after the abuse of African Americans by researchers during the Tuskegee Syphilis Study. Of course, IRB has long been controversial among historians because of its development within biomedical and behavioral frameworks, its focus on anonymized data rather than specific individuals, and its treatment of people as “research subjects” rather than “historians of their own subjectivity” (Brown 2016, 118). Indeed, in January 2017, the federal government finally agreed to “explicitly remove” oral history and historical scholarship from the IRB process (White 2017). Nevertheless, in our experience with this project, the alternative practice of using Oral History Consent forms raised similar problems. Like IRB, the consent forms are designed to offer legibility, protection, and ethical consideration to all participants. We found, however, that the form itself—a formal document produced by our professional institution that we were asking our community partners to sign—often read to our community partners as an affirmation of our institutional power, a signal that they were not actually on equal footing with us, confirmation of their fear that we were trying to take something away from them, and a reminder of past injustices and abuses. This is a problem familiar to many scholars, especially white scholars or scholars representing predominantly white institutions, but working with African American or other marginalized communities. As Jack Dougherty, a white civil rights scholar, explains, “Understandably, many Black Milwaukeeans were highly skeptical or hesitant when I explained the terms of the consent form. Several expressed deep concern that it asked them to sign away their life stories, which I assured them was not the case. A few agreed to be interviewed but did not sign the form. A few others refused to be interviewed at all” (Dougherty and Simpson 2012). The message of theft and disempowerment that these forms transmit, even when that is not their intention, can be a deal breaker for those who want nothing more than to tell their own story, but who fear—with very good reason—that their story will instead be taken away.

Another source of conflict involved the exhibit’s relationship to community-owned photographs, which were a key focus of our endeavors: without them there could literally be no exhibit. However, because African American history is largely absent from local exhibitions and writing about the region, our collaborating partners were both hesitant and sensitive to an important part of their history being told in collaboration with JMU students and professors. For these reasons—not to mention the broader challenge of creating a single narrative that encapsulates an entire community over a large tract of time—the photographs became the flashpoint for much negotiation and at times even conflict throughout the course of the project, and even after it opened. Right up until the week before our hard deadline to send materials to the printer, we were still looking for specific images, and not finding them threatened our ability to tell a coherent and inclusive story, and our ability to deliver on the empowering outcome that we had promised. Several photos had little accompanying information about who was in it, and required a lot of footwork—last minute meetings, emails, and sometimes panicked phone calls as deadlines loomed. Whereas we had initially imagined that we would spend the fall semester tracking down material, and the spring semester composing the exhibit’s narrative, it turned out that it was not until we had begun composing the narrative that many community members had enough trust in the project to be willing to share their materials.

In response to these concerns, we found that developing reciprocal relationships and trust required constant communication, reassurance, and adaptation; it also required a level of time and commitment that ran counter to the pressures of the academic calendar. Doing so forced us to negotiate institutional norms for running engaged projects. Because of the intensity of this labor, we had to modify a traditional class structure to become a yearlong project—labor, it should be noted, that was largely invisible as we were not paid for it and it didn’t count toward our regular course rotations. We began with a fall internship, in which eight students canvassed local archives, trained in digitization and archival methods, digitized materials, and created an annotated bibliography for the class. This was followed by a spring seminar, in which the initial eight students were joined by eight more to digitize materials, compose the exhibit, and publicize the exhibit. Although onerous in terms of our time and our students’ ability, given all of their commitments, to take part in a yearlong class at very specific times, this yearlong class structure not only enabled us to do so much more than a traditional class structure would allow, but it showed a level of institutional and individual commitment that helped allay our community partners’ initial skepticism.

The yearlong class structure also meant that our students had the time to develop a meaningful understanding of the political sensitivities that our work required. Many of them came into the class thinking about their work as a kind of service-learning—a charitable service provided unilaterally to an underprivileged community. The time that they spent on this project enabled them to think both more highly of themselves and more highly of our community partners. They grew to see themselves as research partners, working alongside local experts from a variety of backgrounds, and learning how to manage the conflicts that inevitably arose as expertly as did we. We also increased the students’ sense of themselves as more than just students, and our community partners’ sense of themselves as real partners, by holding numerous class sessions off campus, at the Simms Center, and by convening a Simms advisory board who met regularly with our students to give guidelines, review the students’ work, and make changes and suggestions. These meetings were often difficult to arrange around restrictive student schedules, restrictive university parking rules, and the limited mobility of some of our partners, but they were essential in demonstrating to our students that their work had value and meaning beyond the classroom. They also helped demonstrate to our partners that our students were listening and responding to their suggestions from one meeting to the next, that our partners had a voice in the process, and that they would be proud of the outcome. At the same time, holding our students and the project to this high standard also required additional work on our part. We became our students’ editors rather than simply their professors—holding individual meetings outside of class time to coach individual groups on edits, significantly revising and rewriting their work when necessary, and taking class time to discuss as a group how we felt the public and high-stakes nature of the project had impacted the typical student-professor relationship.

Finally, although we negotiated and renegotiated both institutional norms and our community partnerships as we went along, we ultimately discovered that the exhibit had the potential to become its own single story, not only because some community members perceived our very involvement as a colonizing gesture, but because the community’s desire to create a permanent narrative on the walls of their former school shut down the very real existence of competing stories within the community itself. For example, it became clear after the exhibit opening that while many community members were pleased with the celebratory focus of the exhibit, others wanted to discuss the more painful aspects of their community’s history, and some assumed that we had imposed the celebratory focus on the exhibit rather than developing it in collaboration with our advisory board. The singularity of the story’s narrative arc was also compounded by the physicality and permanence of the photographic materials and the physical site—the fact that once it was up, it could not be easily modified, expanded, or corrected. In other words, we found that while we had found ways not only of inviting as many people as possible to tell the story, we had perhaps failed to keep the storytelling process open and unfinished. As we neared completion of the exhibit, however, we realized that although the transformation of the physical site of the exhibit had been the thing that drew our collaborators into the process of telling the story, the accompanying website had the potential to become a more fluid site where new stories could be added and made.

Building Collective Knowledge: Extending Shared Authority with Participatory Archives

The Celebrating Simms companion website was originally intended to enable the community to access the contents of the physical exhibit without having to go to Simms; we imagined it might be especially useful for high school students and as a record of the project. However, as the project grew, so did the possibilities of its online presence. After we had sent off the final proofs of the physical exhibit to the printer, groups of students experimented with a variety of easy-to-master and largely free tools to develop online storytelling mechanisms. For example, students used a mapping tool called StoryMap, an open source project developed by the Knight Foundation and Northwestern University, to create an interactive map of Harrisonburg, providing place markers for many of the places mentioned in the exhibit and others that did not fit into the narrative.

Along with this spatial rendering of the Simms story, students also created an interactive timeline of key events both prior to and after the story of the Simms school, using another Knight Foundation tool called Timeline JS. This also enabled them to set the Simms narrative in the context of a larger national narrative, which we had not done in the physical exhibit.

These online projects offered students the benefit of learning valuable online storytelling techniques as well as providing the potential to render the central narrative of the exhibit in compelling, interactive formats. The website also allows visitors to interact with the physical exhibit at the Simms Center in different ways. Visitors can click through a slideshow (created in Google Slides) of the exhibit panels that appear as they do on the walls of the Simms Center. A more interactive path is also open to users. This version of the exhibit replicates the text and flow of the physical exhibit, but users are allowed to click on each image contained therein to look at the metadata associated with that image. Metadata, the technical term that archivists use to denote the information that explains the particular exhibit artifact, such as the object’s physical properties and provenance, can provide greater understanding of the artifact itself, as well as providing rich possibilities to cross-reference artifacts. A search for a name, for example, might bring up several documents, such as photographs in which that person is represented, documents where their name is featured, and even as the donor of specific items to the collection. This admittedly simple example quickly reveals how alternative stories can be easily assembled by using the powerful search capabilities that metadata provides.

The possibilities of digital versions of the exhibit materials and the data associated with those properties are important in how we are thinking of expanding the project. What would it be like if we could use the metadata capabilities of Omeka to crowdsource new photographs and the stories they contain? What kind of stories could be told if users could use metadata to cross-reference photographs, and make different narratives based on those associations? What understanding of that neighborhood would emerge if we had at our fingertips an abundance of stories—what new kinds of understanding of history might we arrive at, and what new relationships could be healed or built? Digital humanities scholar N. Katherine Hayles argues that the move toward open-access databases “shifts the emphasis from argumentation . . . to data elements,” and that “web dissemination mechanisms allow for increased diversity of interpretation and richness of insights” (2012, 39). Building on our experience with the online version of the Simms exhibit, we are thinking of the power of such diversity of representation in the next phase of the project. Specifically, we hope to launch another class that expands the remit of the Simms exhibit to invite members of the audience to bring in additional family photographs and other archival items to be scanned and put on the web. These (and the archival items already existing in the Simms project) would be made available without a significant narrative casing. Instead, users would be able to peruse the archive, using the metadata to improve searches and make connections, and when possible to download their own copies and hopefully make their own stories, some of which could be preserved as additions to the physical exhibit, the website, and as photo albums that could circulate among community members.

This idea—a decentralized, web-based archive that contains items contributed by and curated by people who are not necessarily archivists—is not by any means new. Community archives have long been recognized as a counterpoint to institutional, professionally maintained archives in both their purpose and how they are maintained. The concept of a “participatory archive” is a more recent iteration of this alternative to an institutional archive. As archivist Kate Theimer defines it, a participatory archive is “an organization, site or collection in which people other than archives professionals contribute knowledge or resources, resulting in increased understanding about archival materials, usually in an online environment” (2011). As such, a participatory archive has much in common with other crowdsourced knowledge-making mechanisms such as Wikipedia—collection of materials is largely decentralized, and how those materials are described is open to the comments and edits of a community of users rather than a specific authority. As Gilliland and McKemmish argue, participatory archives “reposition the subjects of records and all others involved in the events and actions documented as participatory agents with a suite of legal and moral rights and responsibilities relating to records and archives” (2014, 2).

Although clearly related, participatory archives differ from community archives in one key aspect. Gilliland and McKemmish explain that “a key distinction is that more than one community (for example, one or more source communities, a judicial community, an academic community, the professional archival community) are simultaneously and explicitly involved in and responsible for the creation, management and use of a participatory archive” (2014, 82). To illustrate, the Eastern Kentucky African American Migration Project (EKAAMP) functions as the archive of a specific community (a diaspora of African Americans who partook in an intergenerational migration in and out of eastern Kentucky), is housed on UNC Chapel Hill computer servers, and is also a resource for the community it serves, as well scholars and graduate students. The Digital Archive of Literacy Narratives (DALN) is a participatory archive that invites people from around the world to participate in a specific practice, namely, the creation and sharing of literacy narratives. Like the EKAAMP, the DALN is a community resource supported by university infrastructures and academic research. Interestingly, this model has Institutional Review Board compliance baked into its very structure: to participate in the DALN, users are asked explicitly to allow their work to be accessed and used for research purposes.

Participatory archives, then, are created by and for multiple communities, often in collaboration with institutional archives (Gilliland and McKemmish 2014, 82). The small but growing scholarship on participatory archives tends to focus on the relation between archival items and the technology that supports them. However, it is important to also frame the potentials and challenges of participatory archives in relation to community projects, which is a subject tackled by Gilliland and McKemmish. They argue that participatory archives “become a negotiated space in which these different communities share stewardship—they are created by, for and with multiple communities, according to and respectful of community values, practices, beliefs and needs” (2014, 79). As we move forward with the Simms project (which, because of its online focus, we’re informally calling Simms 2.0) we need to mindfully and expansively think about the design of this negotiated space.

Simms 2.0: Uncovering the Many Stories within the Story of Celebrating Simms

As we have begun thinking ahead about the project with key community partners Robin Lyttle and Billo Harper, we have discussed how we could use the metadata associated with the images to strip away the narrative of the exhibit altogether, allowing interested stakeholders to search and combine archival elements, contribute their own, and build their own stories. It goes without saying that we’re not grasping at a technologically deterministic solution to a much larger problem of historical representation and inequality. Rather, we’re looking toward how artifacts like these photographs can tell new narratives with the aid of digital technologies, to provide a playground where multifaceted accounts thrive in place of the anxious and always incomplete authority of any single story. The messiness of engagement won’t disappear with this new direction: We’ll still need community endorsement and do the very real footwork of moving the project forward.

With all of this in mind, we plan to conduct a second one-semester interinstitutional course, co-taught not only by ourselves but also by Eastern Mennonite University historian Mark Sawin. The first part of the course will be organized around a series of what our collaborator Robin Lyttle calls “memory parties”—events where community members can bring photographs and other materials to be digitized and discussed. After all, although dozens of individuals and institutions contributed photographs and archival materials to the Celebrating Simms exhibit, hundreds more attended the opening and the reunion, and many may have photographs that would add depth and breadth to this archive. Students will be responsible for digitizing and recording metadata for this new material, and for doing research in local archives and newspaper records that could further enrich the online archive. In the second part of the course, community participants will be invited back to explore and interact with the archive, including everything from the original exhibit to all the new materials. Students will be on hand to help participants digitally create photo albums of their own design, giving participants the opportunity to create their own visual narratives, and to add captions that can also become additional metadata for the archive. Using grant money, we can also print these albums for free for anyone who has previously shared photographs with the digital archive, which is important considering that many of our older community participants prefer physical artifacts to digital ones. In the third part of the course, we will hold a community dialogue event at the Simms Center, at which the printed photo albums can be picked up and collaborators can share their multiple perspectives both on the school and on the project, to create what Cauvin calls “space for discussion about the past,” rather than a single story of celebration (2016, 220). Working with Billo Harper, we will also use these various meetings to record videos and interviews with students and participants, which can also become part of the project’s archive online. Finally, depending on time and funds, we may also be able to add a few exhibit panels, photographs, or even narratives taken from participant photo albums to the walls of the Simms Center, or to incorporate participatory techniques such as a comment board or computer lab component into the exhibit itself (Simon 2010), in order to introduce into the physical site itself what public historian Edward Linenthal describes in “Problems and Promise in Public History” as “demilitarized zones . . . where people can engage various, perhaps even irreconcilable, interpretations of our past” (quoted in Cauvin 2016, 220; see also Linenthal 1997).Simms 2.0 is being collaboratively designed with both the gains from and the lessons learned from our first project in mind. The idea of the “participatory archive” is not one that we could have begun with, after all. Deep distrust of our institution’s motives, fears regarding the ultimate ownership and control of the archive, and doubts regarding its accessibility and value meant that no one would have participated (Atiso and Freeland 2016). Because the exhibit provided something of value not only to community members but to all of Harrisonburg, we have now earned some of that trust. With that large project complete, we also now have the freedom to build on that project in single-semester chunks. That said, we do plan to find an off-campus meeting place this time around, so that community members can easily join our class sessions without worrying about parking and accessibility. Finally, we plan to avoid the feelings of disempowerment that consent forms and institutional representatives can create not only by opening up the narrative more fully to multiple perspectives, but also by taking advantage of Creative Commons licensing. Jack Dougherty and Candace Simpson describe this form of licensing as “a licensing tool developed by the open access movement to protect copyright while increasing public distribution” (Dougherty and Simpson 2012). As Elise Chenier explains, in contrast to consent forms that ask “informants to relinquish rights” and thus potentially “violate . . . the principle of empowerment, . . . this form of licensing allows the creator to indicate the ways their material can be used by others . . . ensuring that both the rights and the interests of all parties are fully protected” (2014). There are now six types of Creative Commons licenses, and participants will be able to easily select which of these they prefer, just as they will be able to select how they want to interact with the digital archive, and what story they personally want to tell.

Our experience with this project and our plans for continuing it leads us to believe that, although we are very aware of the various dangers of the single story, we don’t think institutions that are interested in preserving African American history can or should disentangle themselves from the production of stories altogether. In fact, the ideal of empowering outcomes suggests that any institution’s effort to encourage the preservation of local African American archives without the promise of some kind of story will be difficult, largely because the places where historical archives are held have often played a real role in the past production of exclusionary, exploitative, and paternalistic stories. Though fraught by the constant negotiation and renegotiation of authority, trust, and institutional norms, our project’s goal of transforming a community-centered public space into a story of celebration did draw community members into the project, and it did encourage them to share the photographs and oral histories that made the story possible; likewise, the production of a digital companion site has become a way of keeping that story open to continued renegotiation. While we will always need counter-narratives as a first step in decolonizing knowledge, theorizing the productive power of participatory archives might make it easier to use single sites of memory to tell much-needed and more complicated stories from the ground up.

Notes

1 See also White Logic, White Methods (Zuberi and Bonilla-Silva 2008).

2 See also “Contesting Remembering and Forgetting: The Archive of South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission” in Archives and Justice: A South African Perspective (Harris 2007, 289–302). Although postcolonial theorists and decolonial theorists share the same goal of decolonizing, decolonial theorists understand themselves to be grounded in indigenous knowledges and are concerned that postcolonial theory’s grounding in Western theory, Western institutions, Western intellectuals, only perpetuates colonialism (Asher 2013, 832–833).

3 See, for example, Harlem History in New York, Mapping the Stacks and UNCAP in Chicago, DPAAP in Baltimore (Eisenhower 2010), DCAAP in DC, the Black Archives in Miami, or the HBCU Library Alliance. A notable exception to this urban focus is Duke University’s Behind the Veil Oral History Project, founded in 1990. Since 2008, the Council on Library and Information Resources (CLIR) has administered a grant program for digitizing hidden collections in cultural memory institutions nationwide.

4 As several scholars have noted, such quieter conflicts were common in communities across the south, where “one-way desegregation plans . . . closed schools in Black communities, displaced Black teachers, and . . . stereotyped African American children as culturally deprived” (Shircliffe 2012, 87). See also Cecelski 1994, 34–35 and Horsford 2011, 64–70.

5 Key published resources included works by Doris Harper Allen (2015), Billo Harper (2005), Ruth Toliver (2009), Nancy Bondurant Jones (2007), and Vanessa Siddle Walker (1996), as well as a 2013 unpublished paper by Dale MacAllister, which he was kind enough to share with us.

6 Projects similar to ours have also been pursued in nearby communities, including the Josephine School Community Museum founded in Clarke County, Virginia, in 2003, and the “Threads of History: Conversations with a Community” oral history and documentary project in Staunton, Virginia (Moyé et al. 2016).

7 Charles Ballard has persuasively contested this argument, popularized by John W. Wayland (1912; 1927), in a paper presented to the Shenandoah Valley Regional Studies Seminar in 1998.

Work Cited

Adichie, Chimamanda Ngozi. 2009. “The Danger of a Single Story.” TEDGlobal. Accessed March 24, 2017. https://www.ted.com/talks/chimamanda_adichie_the_danger_of_a_single_story.

Allen, Doris Harper. 2015. The Way It Was, Not the Way It Is: A Memoir. Self-published.

Asher, Kiran. 2013. “Latin American Decolonial Thought, or Making the Subaltern Speak.” Geography Compass 7 (12): 832–842.

Atiso, Kodjo, and Chris Freeland. 2016. “Identifying the Social and Technical Barriers Affecting Engagement in Online Community Archives: A Preliminary Study of ‘Documenting Ferguson’ Archive.” Library Philosophy and Practice. Accessed August 11, 2017. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/1377/.

Bachman, Ryan. 2017. African-American Property-Ownership in Downtown Harrisonburg, 1850–1860. PowerPoint presentation at Shenandoah Valley Black Heritage Project.

Ballard, Charles. 1998. “Dismissing the Peculiar Institution: Assessing Slavery in Page and Rockingham Counties, Virginia.” The Shenandoah Valley Regional Studies Seminar Collection, 1995–2009, SC# 5027, Special Collections, Carrier Library, James Madison University, Harrisonburg, VA.

Borg, Kevin, Bradley Andrick, Robin Lyttle, and Dale MacAllister. 2016. Spatial History in the Public Square: Maps, Images, and Archives in the Community. Accessed August 11, 2017. http://www.gtsc.jmu.edu/shps/map/.

Brown, Karida L. 2016. “On the Participatory Archive: The Formation of the Eastern Kentucky African American Migration Project.” Southern Cultures 22 (1): 113–127.

Cantor, Nancy, and Steven D. Lavine. 2006. “Taking Public Scholarship Seriously.” The Chronicle Review 52 (40): B20.

Caswell, Michelle, Christopher Harter, and Bergis Jules. 2017. “Diversifying the Digital Historical Record: Integrating Community Archives in National Strategies for Access to Digital Cultural Heritage.” D-Lib Magazine 23 (5/6). Accessed August 9, 2017. http://www.dlib.org/dlib/may17/caswell/05caswell.html.

Cauvin, Thomas. 2016. Public History: A Textbook of Practice. New York: Routledge.

Cecelski, David S. 1994. Along Freedom Road: Hyde County, North Carolina, and the Fate of Black Schools in the South. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

Chenier, Elise. 2014. “Oral History and Open Access: Fulfilling the Promise of Democratizing Knowledge.” NANO: New American Notes Online 5 (July). Accessed March 24, 2017. http://www.nanocrit.com/issues/issue5/oral-history-and-open-access-fulfilling-promise-democratizing-knowledge.

Cushman, Ellen. 1999. “Opinion: The Public Intellectual, Service Learning, and Activist Research.” College English 61 (3): 328–336.

Dougherty, Jack, and Candace Simpson. 2012. “Who Owns Oral History? A Creative Commons Solution.” Oral History in the Digital Age. Accessed March 27, 2017. http://ohda.matrix.msu.edu/2012/06/a-creative-commons-solution/.

Edwards, Erica R. 2012. Charisma and the Fictions of Black Leadership. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Ehrenpreis, David. 2017. “Replacing the Old, Guard the New: Envisioning Urban Renewal.” In Picturing Harrisonburg: Visions of a Shenandoah Valley City Since 1828, 163–180. Staunton, VA: George F. Thompson Publishing.

Eisenhower, Milton S. 2010. “Uncovering Black History in Baltimore.” The Sheridan Libraries Blog, February 18. http://blogs.library.jhu.edu/2010/02/uncovering-black-history-in-baltimore/. .

Filene, Benjamin. 2015. “Power in Limits: Narrow Frames Open Up American Public History.” In Interpreting African American History and Culture at Museums and Historic Sites, edited by Max A. van Balgooy, 135-146 . Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Flynn, Erin. 2016. “Exhibit Highlights Black History at Simms School.” Daily News-Record, April 21. Accessed March 24, 2017. https://omeka.jmu.edu/simms/files/original/b869094f4885a98730355d0c943a8ede.pdf.

Frisch, Michael. 2011. “From a Shared Authority to the Digital Kitchen, and Back.” In Letting Go? Sharing Historical Authority in a User-Generated World, edited by Bill Adair, Benjamin Filene, and Laura Kolosi, 126–138. Philadelphia: The Pew Center for Arts and Heritage.

Getachew, Wondwossen. 2000. “Lucy Simms Remembered Oral History Project: Interviews with Edgar Johnson, Wilhelmina Johnson, and Louise Winston” (audio recording). James Madison University Special Collections, Harrisonburg, VA.

Gilliland, Anne J., and Sue McKemmish. 2014. “The Role of Participatory Archives in Furthering Human Rights, Reconciliation and Recovery.” Atlanti 24 (1): 79–88.

Godfrey, Mollie. 2016. “Making African American History in the Classroom: The Pedagogy of Processing Under-Valued Archives.” Pedagogy: Critical Approaches to Teaching Literature, Language, Composition, and Culture 16 (1): 165–177.

Gordon-Reed, Annette. 2016. “Memory, Mourning, Mobilization: Legacies of Slavery and Freedom in America.” Remarks at a public summit at the Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello. Accessed March 24, 2017. https://www.monticello.org/site/visit/events/public-summit-memory-mourning-mobilization-legacies-slavery-and-freedom-america.

Green, Kristen. 2016. Something Must Be Done About Prince Edward County: A Family, a Virginia Town, a Civil Rights Battle. New York: Harper Perennial.

Harper, Billo. 2005. Legacy of Lucy F. Simms School: Education During Segregated Times in Virginia. Clinton, MD: Billo Communications, DVD.

Harris, Verne. 2007. Archives and Justice: A South African Perspective. Chicago: Society of American Archivists.

Hayles, N. Katherine. 2012. How We Think: Digital Media and Contemporary Technogenesis. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

HBCU Library Alliance. n.d. “About Us.” HBCU Library Alliance. Accessed August 14, 2017. http://hbculibraries.org/.

hooks, bell. 1994. Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom. New York: Routledge.

Horsford, Sonya Douglass. 2011. Learning in a Burning House: Educational Inequality, Ideology and (Dis)Integration. New York: Teachers College Press.

Jay, Gregory. 2010. “The Engaged Humanities: Principles and Practices for Public Scholarship and Teaching.” Journal of Community Engagement and Scholarship 3 (1): 51–63.

Jones, Nancy Bondurant. 2007. An African American Community of Hope: Zenda 1869–1930. McGaheysville, VA: Long’s Chapel Preservation Society.

Linenthal, Edward T. 1997. “Problems and Promise in Public History.” The Public Historian 19 (2): 45–47.

Loewen, James W. 2006. Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension of American Racism. New York: Touchstone.

Metz, Cheryl. 2005. “Interview with Mary Frances Awkard Fairfax” (audio recording). Massanutten Regional Library, Harrisonburg, VA.

Miller, Elisabeth, Anne Wheeler, and Stephanie White. 2011. “Keywords: Reciprocity.” Community Literacy Journal 5 (2): 171–178.

Moyé, Allan, Marlena Hobson, Amy Tillerson-Brown, et al. 2016. “Threads of History: Conversations with a Community.” Staunton, VA: Mary Baldwin University, DVD.

Shircliffe, Barbara J. 2012. Desegregating Teachers: Contesting the Meaning of Equality of Educational Opportunity in the South Post Brown. New York: Peter Lang.

Simon, Nina. 2010. The Participatory Museum. Santa Cruz, CA: Museum 2.0.

Smith, Graham Hingangaroa. 1992. “Research Issues Related to Māori Education.” In The Issue of Research and Māori, Monograph No. 9. Auckland, NZ: Research Unit for Māori Education, University of Auckland.

Smith, Linda Tuhiwai. 1999. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. London: Zed Books.

Stevens, Mary, Andrew Flinn, and Elizabeth Shepherd. 2010. “New Frameworks for Community Engagement in the Archive Sector: From Handing Over to Handing On.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 16 (1–2): 59–76.

Theimer, Kate. 2011. “Exploring the Participatory Archives.” ArchivesNext. Accessed March 24, 2017. http://www.archivesnext.com/?p=2319.

Toliver, Ruth. 2009. Keeping Up with Yesterday. Self-published.

Tucker, Rob. 2016. “Local History Comes to Life: JMU Students and Community Members Partner to Preserve African American History.” James Madison University News, June 1. Accessed March 24, 2017. https://www.jmu.edu/news/2016/05/20-lucy-simms-exhibit-mm-may-digital.shtml.

Walker, Vanessa Siddle. 1996. Their Highest Potential: An African American School Community in the Segregated South. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Wayland, John W. 1912. A History of Rockingham County, Virginia. Dayton, VA: Ruebush Elkins Co.

———. 1927. A History of Shenandoah County, Virginia. Strasburg, VA: Shenandoah Publishing House.

White, Lee. 2017. “Oral History Research Excluded from IRB Oversight.” AHA Today: A Blog of the American Historical Association, January 19. http://blog.historians.org/2017/01/oral-history-excluded-irb-oversight/.

Zarrugh, Laura. 2008. “The Latinization of the Central Shenandoah Valley.” International Migration 46 (1): 19–58.

Zuberi, Tukufu, and Eduardo Bonilla-Silva, eds. 2008. White Logic, White Methods: Racism and Methodology. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.