Abstract

How can digital engagement deepen the relationships celebrated by community-engaged-learning (CEL) pedagogy—between students and residents, scholars and community members? And how can we prepare our undergraduates—both practically and ethically—to conduct field research that they will later make accessible to a larger public? This article will explore these questions in the context of a Creative Writing and Environmental Studies seminar taught last spring in a small liberal arts college located in rural Maine. First, this essay will examine how community-engaged learning and digital pedagogy practices, when applied together, have the potential to broaden the climate change dialogue by recording and disseminating the voices of those living in rural communities. Second, this essay will outline the principles and procedures that shaped the creation and implementation of the Climate Change and the Stories We Tell course, highlighting student experience and take-aways. Finally, the essay will conclude with a reflection on both the opportunities and limitations that arise when applying CEL and digital pedagogy practices alongside one another.

Introduction

Climate change is slow moving and intensely place-based. It is about the decline of a particular fish or the unusually thin layer of ice on the lake. Things people notice often only when their lives or livelihoods depend upon them. Due to physical and socio-economic marginalization, those living and working in rural areas (where daily life is often more intimately linked to the environment) are the ones least likely to participate in public discussions around ongoing environmental change (Baird 2008). And yet it is in these remote communities where climate change is most profoundly felt. This is particularly true in Maine, where the average temperature has increased 2.5 degrees between 1984 and 2013 (the highest rate in the country, alongside Vermont) and where over 60 percent of residents live in rural areas (again the highest rate in the country). How then are Maine’s farmers, fishermen and fisherwomen, Indigenous peoples, and those working in the winter recreational industry adapting to the warmer weather that is already here? What can their stories teach those of us who live apart from the rhythm of spring melts and warm snaps, both in terms of practical adaptation strategies and in terms of rethinking the ways in which climate change discourse is framed? And perhaps most importantly given the context, how might we design a digital humanities course in which undergraduate students become part of this process, recording, editing, and disseminating first-hand accounts of climate change that might otherwise go unnoticed? In the spring of 2016, I began to explore these questions alongside my students in a community-engaged-learning course I taught at Bates College, called Climate Change and the Stories We Tell.

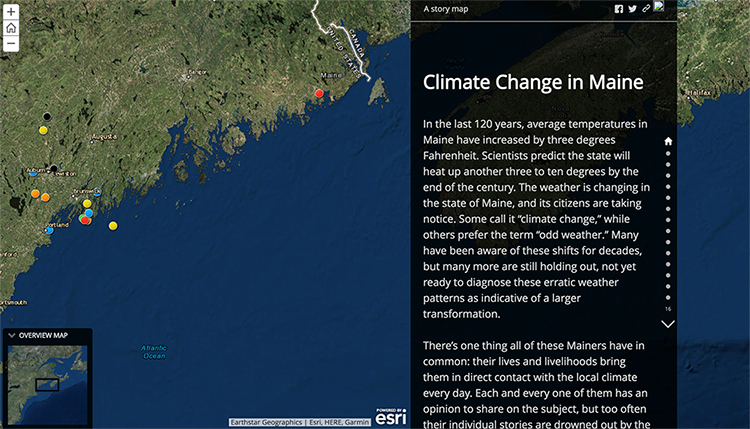

In this course, students interviewed long-standing residents both in Maine’s agricultural belt and on the coast whose lives and livelihoods were being fundamentally altered by climate change. In the most basic sense, their task was to conduct meaningful field interviews while learning how to use the technology necessary to record and disseminate the information they gathered. The class collaborated in the creation of a geospatially tagged online archive to house the multimedia pieces they created (taking many different forms from testimonial-style creative nonfiction essays to podcasts), which they publically launched on the final day of the course (see Fig. 1, below).Their goal then was to create a forward-facing chronicle of the impact of climate change on Maine’s longtime residents that would circulate within multiple public spheres: the Bates College community, the agricultural, maritime, and Indigenous communities profiled, and online.

In the end, it was precisely the public nature of the digital project—both its easily searchable URL and the end of the semester launch event—that gave meaning to the work students produced. They did not put their final products through multiple rounds of revision in order to achieve a better grade; instead they expressed a desire to “get the story right” because it could be read by anybody—the interviewees, the news media, members of the surrounding community, anonymous strangers online. As students worked towards the creation of an online archive of climate change testimonials, they also reflected on the power and privilege inherent in the act of gathering and disseminating the stories of those who might not otherwise publically participate in the discussion and to wrestle with the question of how to adapt real-world encounters to the digital sphere in an ethical, urgent, and engaging manner. Over the course of the semester, each student underwent a profound transformation—from member of the Bates community to Maine citizen—and it is by this metric that the Climate Change and the Stories We Tell course was perhaps the most meaningful.

The purpose of this essay then is three-fold. First, it will explore the ways in which CEL and digital pedagogy practices, when applied together, have the potential to broaden the climate change dialogue by recording and disseminating the voices of those living and working in rural areas. Second, this essay will outline the principles and procedures that shaped the creation and implementation of the Climate Change and the Stories We Tell course, including, where appropriate, both examples of student work and student reflections on the research and production process. Finally, the essay will conclude by exploring both the opportunities and limitations that arise when applying CEL and digital pedagogy practices alongside one another.

Climate Change Communication at a Crossroads

Climate change is one of the most important issues facing humanity. But the very nature of this phenomenon—the physical and temporal scale at which it plays out, the specificity of the scientific language often used to describe it, and the complex set of interests already shaping this discourse—make it a difficult phenomenon to discuss. Scientific papers about climate change tend to be jargon-heavy and largely incomprehensible to the general public. Meanwhile, apocalyptic narratives like those popularized in film and fiction often foster fear, despondency, and withdrawal from the civic sphere (Swyngedouw 2010). Journalistic attempts to cover the topic in a newsworthy manner often end up sounding repetitive, as each month leads to the shattering of yet another climate-related record. Finally, climate change is a deeply polarizing issue, with “believers” and “nonbelievers” often splitting along party lines (Stoknes 2015). The question remains: How can we communicate ongoing environmental transformations in a manner that is engaging and factually accurate, urgent and memorable, pointed and capable of speaking to people of varied political persuasions?

Those whose lives and livelihoods are being directly impacted by climate change often live in rural areas, far from the center of political discourse. Because those who live on the margins of our society are rarely invited to speak for themselves about their own experiences, they are often skeptical of the grounds (both physical and metaphorical) on which the public discussion of climate change takes place. Candis Callison writes about the gulf between local and national vernaculars of climate change in her book How Climate Change Comes to Matter: The Communal Life of Facts (2015). Recalling her time in an Indigenous fishing village in Alaska, she writes, “I experienced not an explicit questioning of climate change but a flat-out rejection of it as a term that described what direct experience with climatic changes feels like and how it is that such changes are understood and discussed” (2015). When warming in the Arctic is examined in public climate change discourse, it often appears either as a statistical anomaly or as a catastrophic event. Neither of which map onto the lived experience of ongoing environmental change and the way it is transforming regional identities, institutional regimes, and epistemological differences at the local level.

In order to begin to overcome some of the fundamental barriers to effective climate change communication, the very site of the discussion needs to shift outwards, towards the communities living on the front lines of this global phenomenon. In Maine, many of the people who are directly impacted by climate change—lobstermen, maple syrup farmers, orchard owners, Indigenous peoples, timber workers—are, like the groups that Callison profiles, reticent to use the terms dictated by national discourse. But, for instance, many will happily relate the very specific ways in which their industry has adapted to the recent string of abnormally warm winters. By including these voices in ongoing discussions about environmental change we can extend the site of discourse while simultaneously eroding the partisan divisions that increasingly frame our larger understanding of the importance of science in society (Horn 2016).

In the spring of 2016, I began to use my own professional experience (I am a creative nonfiction writer in addition to being a professor) to design a course that would reposition the student/researcher not at the center of the climate change dialogue, but rather at its periphery. This course would bring my students into direct contact with those who live (and must attempt to prosper) on the hard edge of environmental transformation. As the Climate Change and the Stories We Tell course took shape, I found myself incorporating different principles of community-engaged-learning (CEL) pedagogy, focusing on how students could collaborate with each other and members of the surrounding community in the creation of a digital archive of climate change testimonials. CEL pedagogy is part of a growing trend that is concerned (and rightly so) with closing the gaps between institutions of higher education and the communities in which they are situated. Ideally, CEL courses unite civic action and scholarly practice by forming reciprocal relationships between students, teachers, and underserved and underrepresented communities. As such, these courses not only aim to improve the lives of those situated outside of the university setting, they offer opportunities for the student to advance their critical thinking skills, reflecting on, amongst other things, the role that privilege has played in shaping the very terms of the engagements which their coursework demands. In this way, CEL pedagogy aims to move beyond the inherently uneven set of power relationships long associated with the service-learning impulse that remained popular in institutions of higher education from the 1960s until the turn of the twenty-first century (Fitzgerald, Burak, and Seifer 2010).

On its own, CEL pedagogy can and does activate more holistic relationships between institutions of higher education and the communities within which they are situated. But what happens when we make this encounter—between students and residents, scholars and community members—public? By training students in basic documentary practices—ranging from audio recording to postproduction interventions like noise reduction, fading, and splicing—I was able to present them with the tools they needed in order to chronicle and later share the interviews they conducted in and around the Lewiston-Auburn area. The students then compiled evidence of these encounters in an online digital archive, which they presented during the public launch event. Had students only published their work online, the public component of the project might have been more easily overlooked or dismissed. However, when students presented the stories that they had gathered to the larger Bates community and to the communities they researched, the project became not only about shifting the discursive grounds on which climate change is discussed, but also about promoting conversation amongst and between the rural communities that are most immediately impacted by ongoing environmental change.

Climate Change and the Stories We Tell Case Study

The Climate Change and the Stories We Tell seminar (cross-listed in both the English and Environmental Studies Departments) took place over Bates College’s five-week-long Short Term. Since students can only enroll in a single course during the compressed semester, the program provides the opportunity to work for extended periods of time off campus. In designing the course, I took advantage of the wealth of resources made available by the college, ranging from its state-of-the-art Digital Media Studios and their audio recording equipment, to the off-campus coastal research center run by a well-staffed community partnership program. That being said, many of the pedagogical interventions described below can be used, with modification, in a more traditional humanities classroom. Instead of giving students complex handheld recorders, you could have them use the “voice memo” application that comes pre-installed on most smart phones. A day-long field trip could replace the week we spent at the Shortridge Research Facility, achieving many of the same pedagogical aims.

Given the condensed nature of the course, I will organize this section of the essay by articulating, module by module, the assignments that led to the creation of the Climate Change in Maine immersive online archive (see Fig. 1 and Fig. 4). Where applicable, examples of student work will be embedded in the essay along with student reflections on the research and production process.

Module One: Introduction to the Art of the Interview

The first week of Climate Change and the Stories We Tell was devoted to developing students’ technical proficiency, their interview skills, and basic climate change knowledge. In class, time was divided between a documentary practices “boot camp,” a structured discussion of the ways in which climate change is manifesting in Maine, and a series of practice interviews. First, Colin Kelly of the Bates Digital Media Studios introduced students to their Zoom handheld audio recorders and to the basic principles of getting quality audio in the field. They then practiced using these devices by interviewing one another. The next day, students returned to the Digital Media Studios where they imported their recorded audio into Final Cut Pro while getting a hands-on introduction in basic audio editing. As they worked on editing their tracks, we discussed what was working and what wasn’t, both in technical terms (i.e., ambient noise, microphone distance and direction) and in terms of interviewing best practices (what kind of research is needed to conduct a successful interview, how to handle broaching difficult-to-discuss subjects, and how not to lead the interviewee).

Next, students interviewed each other a second time, this time with an interview prompt: Describe a moment in your life when you wanted to speak up, but didn’t. That night for homework each student transcribed the interview they conducted and edited whatever section they found most engaging into a one-page story or a one minute audio clip, using only the words of the speaker. The following day in class, the students exchanged the stories they produced. The student interviewee was invited to critique their peer’s rendition and together the teams entered into an open dialogue about the power dynamics at play in testimonial storytelling. Towards the conclusion of the documentary practices “boot camp,” students completed a technical- and digital-literacy questionnaire and were partnered (for the remainder of the semester) with someone whose aptitudes complemented their own.

A strong companion text for this initial interview module is Svetlana Alexievich’s Nobel Prize winning Voices from Chernobyl (2005). In Voices from Chernobyl, those who lived near the infamous power plant speak of their own experience of the nuclear explosion and its aftermath. Alexievich conducted hundreds of hours of interviews, transcribing these conversations, and transforming them into lyric essays that bear witness to not only one of the largest environmental disasters in modern history, but also to the collapse of the Soviet Union. As students read, I asked them to try to imagine the research Alexievich conducted in advance of her interviews, the questions she likely asked in order to unearth the stories collected therein, and the extent to which Alexievich edited her transcriptions in order to arrive at the final product. While reflecting on the potential story behind Voices from Chernobyl, students began to make connections between Alexievich’s writing process and the fieldwork they would soon conduct. In this way, Voices from Chernobyl served as a kind of oblique guide to the art of the interview and as an introduction to the ethical and philosophical questions that define the testimonial genre.

Prior to the first week of classes (and in collaboration with Sam Boss of the Bates College Harward Center for Community Partnerships), I contacted six people from the immediate area whose work is dependent upon the environment—a beekeeper, a raspberry farmer, a member of the Stanton Bird Club, a Wabanaki historian, a forester, and a bait shop owner. Together we arranged specific times for each person to come to campus to be interviewed by my students. During the latter half of the first week of classes, student teams researched climate change and its impact on different aspects of the local environment in order to prepare to interview the above-mentioned community members. Each student team submitted a list of potential interview questions, which the class reviewed in advance of the first round of interviews, weeding out those with yes or no answers and those that closed avenues for further discussion.

These initial interviews took place in the Digital Media Studios on the Bates College campus, and, as such, provided students the opportunity to practice their new skills in a controlled and familiar environment. Together, Sam Boss and I greeted each interviewee when they arrived on campus. In these initial in-person encounters we were careful to outline the scope of the project and its public components. And while we did not need to get written consent from interviewees (since the interviews were not going to be turned into searchable data and as such were not subject to Institutional Review Board (IRB) protocols) we did attain verbal consent from each participant. We then introduced the student teams to the community member to which they had been assigned and the interviews commenced. During this phase, each student team had the opportunity to interview at least two different community members. While I was always on hand to help student teams with any issues that may have arisen, I was rarely present in the room in which the interviews were conducted. My absence gave the students the opportunity to work through the process themselves. By the end of these initial interviews, students had acquired the confidence to navigate both technical and interpersonal “glitches” as they occurred in real time.

During the second week of the course, students took their skills on the road, conducting interviews with community members in the greater Lewiston-Auburn area. Again, I pre-screened interviewees and student questions, and arranged times and locations for the scheduled interactions. I arrived a few minutes prior to each interview, introduced myself to the subject, and answered any questions he or she had. Once the students arrived and I introduced everyone I left, incrementally increasing student autonomy.

For the second half of the first module, students were asked to read other famous “testimonial” style works, including the classics of Native American “autobiography” My People, the Sioux by Luther Standing Bear (2006) and Black Elk Speaks by John G. Neihardt (2010), Let Us Now Praise Famous Men by James Agee and Walker Evens (2001), The Dispossessed by Alfredo Molano (2005) and Anna Deavere Smith’s “Four American Characters” (2005). They were then asked to compare these works to Alexievich’s text, considering, in particular, the extent to which the author’s role in shaping the artifact is made overt by the text itself through any number of interventions ranging from a framing introduction, to titling, physical embodiment, and use of the first-person “I.” As we discussed the benefits and drawbacks behind each approach, we explored questions of what it means to “speak” on someone’s behalf, if there are marked differences between writing another’s testimony and acting as a compiler or activator of their text, and what differentiates testimonial writing from autobiography or historical fictions (Beverly 1996).

Here you will find an audio testimonial that a student team (Hannah Loeb and Tyler Parke) recorded during the first module and which they ended up including in the immersive online archive. Ms. Loeb and Mr. Parke chose to follow Alexievich’s example, editing out all traces of the interviewer and allowing the interviewee (Stan DeOrsey) to speak for himself about his own experiences as a longtime birder in Lewiston.

Nell Hourde, one of the students in the class, remarked that the very process of recording and editing the testimonies of local people with deep knowledge of ongoing environmental change challenged her definition of intelligence. She said: “Right away the class made me reflect on my own privilege, and how it shaped my narrow-minded understanding of what knowledge is and who has access to it. When interviewing someone who possibly does not have a college education—a fisherman or a farmer or an immigrant—at first there is this weird expectation of the amount of education relating directly to the amount of knowledge that person has. But, as I found time and time again, I was always the one learning by listening to people who have accrued a lifetime of knowledge—outside of the classroom—and they are the ones sharing that knowledge with me.”

Module Two: Immersion

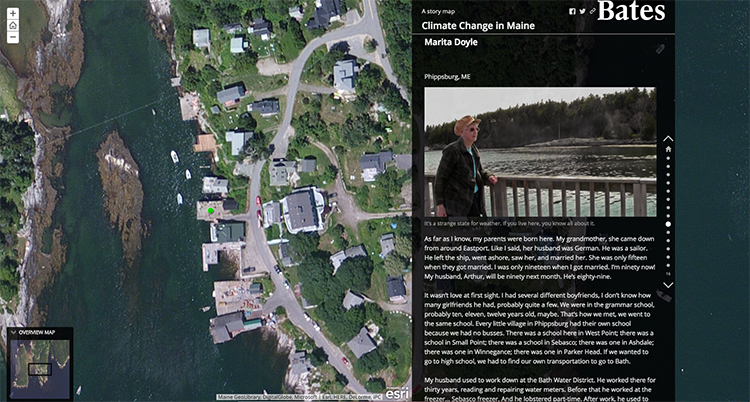

During the third week of the course, students were stationed at the Bates-run Shortridge Research facility in Phippsburg, Maine. This coastal location provided them with direct access to Maine’s iconic lobster industry and other coastal communities being fundamentally transformed by record-breaking warming in the Gulf of Maine. While at Shortridge, student teams were responsible for all aspects of the interview process from tracking down subjects and arranging meeting times to carrying out and transcribing their interviews. On the first afternoon, Laura Sewall, the Director of the Coastal Center at Shortridge, gave students a tour of the Phippsburg Peninsula, pointing out locations where they might encounter potential participants—the docks, the general store, the local library, and the local land trust. At the close of the tour students were also handed a list of people who had been prescreened and had agreed to be interviewed. Students need not contact any of the people on the list, but if they had a difficult time tracking down participants or were nervous about speaking to strangers then they could use the list as an additional resource.

At this point in the term, my role in the classroom changed from facilitator to editor. I scheduled two meetings with each student team throughout the week. In the first meeting, we discussed their progress both in terms of hunting down and meeting with interviewees and with the labor behind documentary production. Had students, for instance, transcribed all of their interviews? Were they logging their audio? How were they organizing their photographic evidence? If students were carrying out interviews but had not yet begun to sift through the material they were collecting, I gave them a homework assignment along these lines to be submitted prior to our next editorial meeting. In the second meeting, we discussed how they might edit their collected testimonies for a public audience, considering narrative arc, dialect, accompanying visuals, and the potential role of the narrator. At this point, I asked whether the student planned to share a draft of their final product with their interviewee in order to get feedback from the source. We reviewed the benefits—fact checking, potential expansion of original story—and drawbacks—interviewee may wish to sanitize the language they initially used or remove a particular section entirely—to this kind of collaborative approach.

A useful complementary text for this portion of the course is Per Espen Stoknes’s What We Talk About When We Try Not to Think About Global Warming (2015). This book outlines some of the fundamental barriers to effective climate change communication and proposes new strategies for how to talk about climate change in ways that might support transformational activities, create positive solutions, and overcome political partisanship. What We Talk About When We Try Not to Think About Global Warming helps students to contextualize the testimonials they have been gathering within the climate change discourse and provides a jumping off point for students to think about how their work might expand and reshape the very grounds on which this discourse takes place.

Module Three: Toward a Public Presentation

Students returned to the Bates College campus for the fourth and fifth weeks of the semester, meeting daily in the Digital Media Studios to transform their audio recordings and photographs into a suite of multimedia pieces that chronicle the ways in which Maine’s agricultural, industrial, and Indigenous communities are already adapting to the challenges presented by climate change. In the fourth week, students worked in their teams to create two “finished products” that would be housed in the student-run online archive. This work often took the form of a transcribed and edited interview, modeled after Svetlana Alexievich’s Voices from Chernobyl, or of a work of creative nonfiction, modeled after James Agee’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. However, where technical literacy was already high, teams often chose to create podcasts and audio testimonials by editing their collected recordings in Final Cut Pro. During this phase of the project, I regularly conferenced with the student teams, offering continued editorial advice while also helping them to set reasonable goals for their final projects, given the time constraints under which they were working. Below you will find an example of a student-made podcast where the interviewers, Julia Dunn and Nell Hourde, have chosen to act as the first-person narrators, placing the interviews they conducted with locals working in the lobster industry within the larger framework of ongoing warming in the Gulf of Maine.

During the fifth week, students took on an editorial role, reading and revising their peer’s work and organizing their selections for inclusion in the Climate Change in Maine immersive online archive. We decided together that the rights to all of the material in the archive would be held under a Creative Commons license and as such would be available for others to reuse with attribution. Students uploaded their final projects to the archive through Esri’s Story Maps platform, geospatially tagging each story to the location where the events chronicled therein took place. With Esri’s Story Maps, members of the humanities community can, with no coding experience, represent narrative stories alongside geographically integrated metadata and other artifacts. This relatively new online platform was integral in the creation of our forward-facing archive. Students looked to ProPublica’s award-winning Losing Ground website as a model because it highlights the power of braiding together multiple forms of media and data to create a single interactive web-application that illustrates change in place over time.

The project illuminates well the ideas of historical geographers like Anne Kelly Knowles. The essays in her edited collection, Placing History: How Maps, Spatial Data, and GIS Are Changing Historical Scholarship, contend that utilizing Geographic Information Systems (GIS) helps researchers to illustrate what text alone cannot (2008). For example, the power of Ms. Doyle’s story of the impact of warming in the Gulf of Maine on her family’s livelihood (see Fig. 4) comes, in part, from its being located on a map alongside parallel stories of environmental transformations taking place in other communities across the state.

As Shawn Graham writes in Digital Pedagogy in the Humanities, “the very act of making outward-facing work is transgressive and transcends the closed systems that have long defined institutions of higher education” (2016). When we create forward-facing work that is, itself, a record of an unusual encounter—between students and residents, scholars and community members—the process itself fosters engagement amongst communities that are not always in direct contact. In the Climate Change and the Stories We Tell course, students conducted field interviews in multiple communities adapting to a similar set of environmental transformations. The iterative nature of this process was, surprisingly, key to its success. The more interviews students conducted, the more they learned about the varied and multiple responses to climate change taking place in Maine. Students carried the knowledge they acquired from Maine’s residents forward with them into each subsequent interview. They shared, for instance, news of the ways in which farmers were adapting to warmer winters with the lobsterman they interviewed on the coast, acting as conduits (as opposed to sources) for information as it moved between different rural communities. In so doing, this process (along with the archive itself) deepened a whole set of reciprocal relationships—between Bates College and the surrounding communities, and also between residents scattered across rural Maine, momentarily overcoming great social, economic, and geographic distances.

Henry Colt, one of the students in the class, had this to say about the cumulative and transformative nature of the interview process: “Too often, students and professors talk about people whose lives may be affected by some issue—climate change or racism, for example—without ever coming into contact with those people. What was special about this class was that Elizabeth made sure we did run into the people we were talking about—and that we ran into them often. For every hour spent in a classroom or in front of a computer, two were spent in a bait and tackle shop, on a berry farm, on the steps of a Phippsburg general store at sunrise. The more people we talked to, the fewer assumptions we made—we were learning to listen. And we carried the information we learned from residents into each subsequent interview.”

The course concluded with a public launch (Fig. 5) of the Climate Change in Maine website with interviewees, local newspapers, citizens of the greater Lewiston-Auburn area, and members of the Bates community all being invited to participate. The event opened with a performance by the student-run Mount David String Band, infusing the occasion with a ceremonial atmosphere. During the launch, each student presented their final work and “published” it to the immersive online archive, making it widely accessible to the public. Finally, the launch concluded with a question and answer period where students fielded inquiries from local newspapers and members of the surrounding community. Throughout the term, the launch event served as a specific goal for students to work toward. It also made the public component of the project overtly tangible. Had students simply published their work online without presenting it to members of the surrounding community, the work would have been able to circulate with relative anonymity. When specific students were responsible for sharing the specific voices of their fellow community members publically, they experienced an additional feeling of responsibility both to the story and to their interviewee.

Reflections

In Climate Change and the Stories We Tell, students were empowered by their acquisition of digital skills ranging from basic fluency in Final Cut Pro to the ability to generate content in a GIS-driven mapping platform. By drawing upon journalistic, computational, and creative practices, students explored the ways in which nonfiction writing and computer science can help to integrate and centralize the voices of those living in rural areas. But, in the end, I wonder whether the centralization of these voices ought to be the primary marker against which the project’s success is measured. While the Climate Change in Maine website continues to get a small but steady number of regular visitors, the conversations that took place between members of different communities by way of my student’s interviewing practices might, I suspect, have a more lasting impact on those who participated in this project than the website itself.

One comment that I heard time and time again from students was that the people they interviewed were not aware of the impact of environmental change on other agricultural, industrial, and Indigenous communities across the state. For example, when a lobsterman on the coast heard from the student interviewer that warmer winters were also having a negative impact on apple farmers a hundred miles inland, he was surprised. And from that surprise came the realization that the environmental changes reshaping his industry were far wider ranging than he had originally understood. In this way, a course such as Climate Change and the Stories We Tell has the potential to create common ground amongst disparate groups that are all being transformed by the same large-scale environmental phenomenon. In so doing, it provides opportunities for information transfer amongst and between the historically marginalized.

The question then becomes, how can we share this kind of information amongst these groups as effectively as possible? The one-on-one interaction recalled above is, in and of itself, impossible to scale. While the digital online archive is a start, it demands that users have both internet access and basic computer proficiency, two prerequisites that are not to be taken for granted in rural communities. And while the final launch event served as an opportunity to share the work with the profiled communities, due to the timing of the event (midday, midweek) only a handful of interviewees were able to attend. Going forward, in an effort to further deepen the reciprocal relationships between institutions of higher education and the surrounding areas, it would make sense to carry the information gathered back into the communities profiled by holding a series of small-scale launch events at easier to access locations and at times when working people are more likely to attend.

The online immersive archive students built in collaboration with local community members bears witness to the lived experience of climate change in Maine. As such, it articulates ongoing examples of resilience in place, reshaping our ideas about how we can respond to climate change and perhaps even offering a glimpse of a future from which we need not collectively recoil. But in the end, the success of the Climate Change and the Stories We Tell course cannot be measured by the artifact alone. Instead, it ought to be measured by the shared experience of students and community members, the interactions that led both to see climate change from new and unexpected perspectives, and the ways in which it encouraged dialogue amongst and between those living on the margins.

Along these lines, I feel inclined to give the last word to one of my students, Nell Hourde, who said: “The most important thing is to . . . have conversations so people with different ideas and different backgrounds can continue to talk to each other and work towards a common understanding. But also, sometimes this is the most difficult thing to do, just to sit down and talk to someone you don't necessarily agree with. Often, I feel like this kind of work is pushed aside as unnecessary, unacademic, and "soft," for lack of a better word. But this is how actual change happens and this is how people actually communicate their ideas to each other. It is so important! And not soft at all.”

Work Cited

Agee, James, and Walker Evans. 2001. Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Alexievich, Svetlana. 2005. Voices from Chernobyl: The Oral History of a Nuclear Disaster. Translated by Keith Gessen. New York: Picador.

Baird, Rachel. 2008. Impact of Climate Change on Minorities and Indigenous Peoples. Briefing Paper. London: Minority Rights Group International.

Beverley, John. 1996. “The Margin at the Center: On Testimonio.” In The Real Thing: Testimonial Discourse and Latin America, edited by Georg M. Gugleberger, 23–41. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Callison, Candis. 2015. How Climate Change Comes to Matter: The Communal Life of Facts. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Fitzgerald, Hiram E., Cathy Burak, and Sarena D. Seifer, eds. 2010. Handbook of Engaged Scholarship: Contemporary Landscapes, Future Directions, Volume One: Institutional Change. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Press.

Graham, Shawn. 2016. “Digital Pedagogy in the Humanities: Concepts, Models, and Experiments; History.” MLA Commons. Accessed February 1, 2016. https://digitalpedagogy.mla.hcommons.org/.

Horn, Miriam. 2016. Rancher, Farmer, Fisherman. New York: W.W. Norton.

Knowles, Anne Kelly, ed. 2008. Placing History: How Maps, Spatial Data, and GIS Are Changing Historical Scholarship. Redlands, CA: Esri Press.

Molano, Alfredo. 2005. The Dispossessed: Chronicles of the Desterrados of Columbia. Translated by Daniel Bland. Chicago: Haymarket Books.

Neihardt, John G. 2010. Black Elk Speaks. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

Smith, Anna Deveare. 2005. “Four American Characters.” TED: Ideas Worth Spreading. https://www.ted.com/talks/anna_deavere_smith_s_american_character.

Standing Bear, Luther. 2006. My People, the Sioux. Lincoln, NE: Bison Books.

Stoknes, Per Espen. 2015. What We Talk About When We Try Not to Think About Global Warming: Toward a New Psychology of Climate Action. White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green Publishing.

Swyngedouw, Erik. 2010. “Apocalypse Forever? Post-Political Populism and the Spectre of Climate Change.” Theory, Culture & Society 27 (2–3): 213–232.