Creative Time's Black Radical Brooklyn

In fall 2014, I found myself in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, looking for the Weeksville Heritage Center, the rediscovered site of a self-sustained community of freed slaves. Four of the original row houses, built in the mid-nineteenth-century, sit across a field of grass and wildflowers from a modern glass, wood, and stone community and arts center. The site is in the literal shadow of the recently shuttered St. Mary's Hospital.

Weeksville, and not the empty hospital, serves as the intellectual and spiritual center for the Creative Time installation Funk, God, Jazz, and Medicine: Black Radical Brooklyn that spread out over the neighborhood. Each subject was tackled by an artist in collaboration with a community center or site. I was there—a queer, white, biomedical scientist—to experience Medicine, an installation by Simone Leigh.

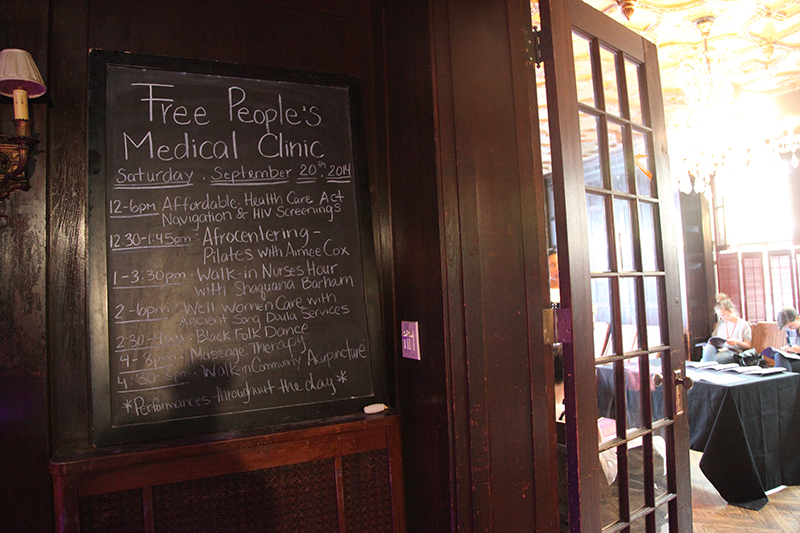

Leigh's work, Free People's Medical Clinic, was situated in a former mansion and combined performance, installation, and medical practice. Even with the midday heat, the mansion was dark and cool inside, low purple light and music beating through the space. Black women in nineteenth-century nurses uniforms offered to take one's blood pressure on the front stoop. Inside, black women at tables offered up the day's class schedule and the possibilities for care. I wandered through the mansion slowly. There was no aesthetic center, nothing exactly to look at. I watched people wandering in, many looking a bit uncomfortable in this still-black corner of Bed-Stuy, signing up for free acupuncture, yoga and dance classes, or ob-gyn care.

What, one might ask, is so radical about medicine? The shadow of a shuttered hospital—and the associated structural violence of heath deserts—for one. And the fact that caring for oneself and others in the face of this type of institutional violence is a radical act, "an act of political warfare" (Lorde 1988, 131). And the all-too-rare consideration of what types of bodies have been most likely to offer care without receiving any in return (Washington 2006). Leigh has built an, albeit temporary, intervention responding and proffering solutions to historical and contemporary acts of violence perpetrated by the biomedical and medical sciences against black and brown bodies, women, and queer people.

The medical and biomedical sciences have profoundly altered not only the ways in which we deal with our bodies and the inevitability of disease, but, especially in the modern genomic era, also how we understand and view identity, culture, and privacy (Holloway 2011; Roberts 2011; Nelson 2016). Scholars and artists have engaged with this rapidly changing landscape to contextualize the science; scientists and doctors have pushed forward in their self-described quest for knowledge, for understanding, for healthier bodies and minds. Yet, we know that health, like other resources, is unequally distributed; further, the medical sciences have used black bodies, women in particular, to gain knowledge, all while building or participating in systems that make health resources inaccessible to these communities (Washington 2006; Farmer 1999). Our systems have failed, but many within these systems have failed to notice.

Why was Leigh's intervention necessary? How and why would an artist consider the facilitation of medical care as part of an art project? How can such artistic interventions challenge the systems that typically build medical technology and deliver bodily care? All our modern systems have failed to reduce class- and race-based health disparities; with the failure of "rational" science, it is perhaps time to look elsewhere, to look toward the irrational, the artistic, the "otherwise." Despite the great promise that the modern biomedical sciences offer, DNA sequencing cannot fix societal ills. If we do not change course quickly, the biomedical sciences may only serve to entrench centuries-old biases, and the cost will continue to be black, brown, female, and poor bodies used and studied only to save others. Art may be well placed to confront and correct this history and to build a more just world where health care in poor and black neighborhoods is no longer a noteworthy exception, but an embodied, artful reality.

Simone Leigh's Medicine

Through Black Radical Brooklyn, Creative Time asked artists to engage with the community in and around the Weeksville Heritage Center. The decision to center the installations at Weeksville was a significant one. Because of a lack of institutional support and systemic violence, black communities have had to build institutions for their own care, such as Weeksville. As elaborated in Creative Times's curatorial statement:

This month-long exhibition draws inspiration from Weeksville's incredible story of achieving self-determination through creating and preserving an intentional community of refuge and Black power. It also acknowledges the continued legacy of individuals, institutions, and movements that have sustained Weeksville's core values in the contested landscape of Crown Heights and Bedford-Stuyvesant, from the nineteenth century until today. (Thompson, Bumbray, and Eterginoso 2014)

Leigh partnered with Stuyvesant Mansion, a community center that offers doula services and ob-gyn care in the former home of Josephine English, one of the first female ob-gyn providers in New York State. English and her practice delivered thousands of children in the house (Creative Time 2014). The geography of the site, therefore, is profoundly rooted in self-determination, community care, and work by and on black and female bodies.

Leigh's work announced itself in its title: Free People's Medical Clinic. Within the house itself, and throughout the installation, were images from the original Free People's Medical Clinics opened by the Black Panthers in the 1970s. The Black Panthers were a revolutionary political party with extensive social programs, started in 1966 in Oakland, California (Nelson 2011, 3). The clinics were part of the Panther's social outreach project and a response to their belief in the inherent racism of the medical apparatus built by the state and private enterprise (Nelson 2011, 75–114). The clinics offered physical exams, minor surgeries, blood test and laboratory work, a Sickle Cell Anemia program, and treatment of common infections and ailments, provided by volunteer medical professionals. The clinics were committed to democratizing medical knowledge: doctors and nurses trained community members in medical and laboratory procedures in order to make the clinics self-sustaining.

The majority of care in Black Panther Party clinics was given by black women. According to Alondra Nelson, even though the Black Panther Party had an analysis on sexism and women, and had women in positions of power, female caregivers reflected the traditional role of women in society at large (Nelson 2011, 89, 96). Leigh connects to this historical role by having women alone offering care in a work curated by a black woman and created by a female black artist.

Leigh's clinic focused on preventative and self-care: yoga and dance classes, acupuncture, and massage. Leigh explained to me that when any care is difficult to come by, opportunities for nontraditional care (e.g., yoga) either do not exist or are economically unavailable to many in the neighborhood. Her project embodies the belief that such modes of care are also valuable to the community (Osmundson 2014).

Leigh originally planned to offer primary care as well, but Creative Time could not afford to insure the facility for that purpose. 1 Ironically, the very litigation that was designed to protect patient interests has served to solidify healing power in the hands of corporations large enough to bear the insurance burden. The risk of litigation has limited the ability of medical care professionals to offer any official care outside of existing institutions (Osmundson 2014).

The choice of nineteenth-century nurses uniforms and the fact that all the bodies giving care within the installation were female evoked The United Order of Tents, a fraternal organization started by black nurses in 1848, named for the temporary tents they constructed to give care during and after the Civil War (Spellen 2011). A brownstone near Stuyvesant Mansion that was for sale during Leigh's research phase was once owned by the United Order of Tents (Spellen 2011). The Order of Tents was secret for much of its existence; black bodies caring for other black bodies was a dangerous, occasionally illegal, activity. Leigh's work is an embodied performance of the scholarship on the Black Panthers and the United Order of Tents. She makes the care of bodies in a black neighborhood a public enterprise, blurring the lines among caregiver, artist, and scholar. Leigh stated,

I was really shocked that most people I know have never heard of [the United Order of Tents], which made me think about how many black histories we still don't know. A lot of black life, for practical reasons, happened in secret. If you can't be completely human in public, maybe you can do that privately. It peeks out every now and then. But in these private rooms, a lot of culture is developed. (Osmundson 2014)

Leigh took care to both maintain and blur the line between public and private, performance and care. Her caregivers, teachers, and doulas gave care in safe and private spaces. Most of the classes were held behind closed doors. She offered spaces exclusively for LGBTQ people of color, as well as yoga classes only for people of South Asian descent. This work speaks to intersectionality—e.g., bodies that carry simultaneous and overlapping oppressions (Crenshaw 1991)—and how those bodies require special care and safe keeping. It also is mindful, in the case of yoga classes by and for those of South Asian descent, of the appropriation of culture as care.

Leigh's installation, explicitly in conversation with the Black Panthers' health clinics, attempts a modern-day equivalent, contextualized as an artistic enterprise. Given what Leigh described to me as the long historical context of biomedical violence against black bodies and the ongoing struggle to get quality primary and preventative care in this part of Brooklyn, Leigh's work is indeed both black and radical as it rejects facile definitions of medicine and care and reimagines care both by and for black bodies in a historically black neighborhood.

Health Deserts and Unequal Access to Care

Walking between Crown Heights, a neighborhood with a large population of immigrants from the Caribbean, and Bedford-Stuyvesant, a historically black neighborhood, limited access to health care becomes apparent before stepping into any of the installations. There's not only the massive, shuttered St. Mary's Hospital, but also another recently closed hospital only blocks away. These hospitals were struggling financially due to a common problem in underserved communities: low rates of health insurance for their largely poor patients (and low cultural trust between the community and health care institutions), who have limited access to preventative care and high rates of emergency room use as their first interaction with care. Hospitals treat uninsured patients in emergency rooms, but because many can not pay their substantial bills, this becomes a financial burden for the institutions, as well as the individuals (Benson 2014).

Scholars have long documented the ways in which health disparities are driven by geography, class, race, gender, and sexuality. For example, black women in Chicago are twice as likely to die from breast cancer as white women. White women are more likely than black women to receive a diagnosis of breast cancer, but black women are more likely to die largely due to low rates of insurance and fewer health care centers in black neighborhoods (Roberts 2011, 123–127).

These disparities are not an exception to the rule, but rather underlie broad trends in public health. Paul Farmer, a doctor and anthropologist, elaborates how the burdens particular to working class women and women of color lead to dramatic differences in health outcomes. Women are more likely to be caring for family members; poor neighborhoods can have large health deserts that make accessing care difficult (Farmer 1999, 63–66; Farmer 2003, 43–50). This is systemic medical violence and contributes to morbidity and mortality along the lines of race, class, and gender, in America and abroad.

Leigh's installation responds directly to both the historical lack of quality care in poor neighborhoods and to the increasing disparities in access driven by the structure of the neoliberal health care market, wherein hospitals must remain profitable to stay afloat.

The Use of Black and Brown Bodies As Research Tools

A great irony is that the burden of medical research has also been unevenly borne. For hundreds of years in this country, black bodies—particularly female—have been commonly used for medical research, often with improperly informed consent or none at all. Once techniques or technologies are developed and available, structural inequities make these same bodies the least likely to receive the care that they were used to create.

The Tuskegee experiment, wherein black men in the rural south were not given treatment for syphilis in order to determine its course of infection (Washington 2006, 177–178), is commonly related as a worst-case-example of what can go wrong in medical experimentation. Less well-known is that the men enrolled in the study unknowingly served as human incubators for Treponema pallidum (the cause of syphilis) for decades, which allowed large quantities of the bacteria to be cultured (cultures grew poorly or not at all in laboratories). These cultures were then used to develop tests for the infection. Medical historian Harriet Washington places the Tuskegee experiment in the long and harrowing context of medical experimentation on black bodies, from the inception of our nation through the twenty-first century (Washington 2006).

Particularly relevant to Leigh's project is James Marion Sims, the "father of American gynecology," who, in the nineteenth century, experimented in surgical procedures on female slaves, whom he purchased for that purpose. As his property, they could not consent. He did not use anesthetics as he tested different materials for vaginal sutures to close incisions used to treat vesicovaginal fistulas (Washington 2006, 61–70; Holloway 2011, 45–47). Sims wrote that black women do not feel pain to the degree that white women do (Holloway 2011, 47). Scholar Karla Holloway places Sims in the long history of violence-as-public-spectacle against black bodies. While his surgeries on white women were private, his surgeries on black women were public spectacle, open to other doctors and lay people in his barn (Holloway 2011, 46). Given this context, Leigh's decision to have limited public dance and yoga performances and provide care behind closed doors is particularly important. The black female bodies that performed care in Leigh's exhibition invert this centuries-old spectacle of black suffering.

There is a clear line between the development of the field of genetics, its use in controlling human populations (eugenics), and the development of the birth control pill (Roberts 1997; Washington 2006; Holloway 2011). Margaret Sanger, the founder of Planned Parenthood (Roberts 1997, 72–76), convinced policy makers and the biomedical community to develop the birth control pill in collaboration with eugenicists, who had an overt interest in controlling the reproduction of black Americans (Roberts 1997). Because birth control was illegal in the US at the time, clinical trials were held in Puerto Rico, and therefore used non-white, healthy women of reproductive age to test a drug of unknown long-term effects (Holloway 2011, 47–50). The dose used on women in Puerto Rico was 60 times more than the dose approved by the FDA for daily use (Holloway 2011, 49). Whether informed consent was used in these trials is unclear. What is clear is that birth control was subsequently used to control the reproduction of undesirable communities, especially poor communities of color, into the 1990s (Roberts 1997; Washington 2006).

History repeats itself. From the 1950s through the 1970s, under the guise of vaccine research, children at New York's Willowbrook State School (for the developmentally disabled) were injected with live hepatitis virus; parents were able to hasten admission to the school by signing up for the "study" (Holloway 2011, 112). In the 1990s, the CDC came under fire for testing a measles vaccine in infants as young as four months, targeting black and brown children in Los Angeles, Haiti, Peru, Thailand, Cameroon, Egypt, Zaire, and other countries (Holloway 2011, 126). Children were given doses of an experimental vaccine without indicating that fact, at ten to 500 times the usual dose. In 2015, 250 children at a Texas immigration detention center were given an adult dose of the Hepatitis A vaccine, leading to acute fever and pain (Flynn 2015).As Holloway argues, these "studies" and subsequent accidents affect those most vulnerable by the intersection(s) of their identities (Holloway 2011, 101–136). Policy and law have shifted in the last several decades to protect individuals by requiring informed consent. There is ongoing debate about further protecting patients in the consent process, with scientists and doctors calling the new regulation "onerous" (Stein 2015). Clearly, for the most vulnerable populations, history isn't history; it remains embodied violence.

Constructing Biomedical Inequity

Access to hospitals, doctors, and preventative care is only one layer of the medical and biomedical power structure. Drugs and technologies are designed and developed for those who can pay (Ridley, Grabowski, and Moe 2006). Which diseases to study and which to ignore are decisions about which bodies to value and which to let die. This power and violence is too often hidden within bureaucratic, political, or scientific debates, but it has been named in scholarship and understood in activism for decades (Foucault 1990; Nelson 2011).

Sickle Cell Anemia is a rare blood disorder most commonly found in Americans of African decent. It had received little research attention, while disorders that affected fewer individuals, but that did not predominantly affect the black community, had been well funded by the state. This brought Sickle Cell Anemia to the attention of black health advocates, including the Black Panther Party, who advocated for increased visibility and research. The Panthers did not wait for institutional recognition from the state or the predominantly white medical infrastructure; rather, they built their own institutions in order to test for Sickle Cell Anemia in black communities, to counsel carriers of the trait, and to advocate for patients as they interacted with doctors for treatment (Nelson 2011, 115–152).

Even the basic biomedical or genetic research that considers race and behavior has been rife with ethical issues and misunderstandings of sociological complexities. A 1997 study based at Columbia University administered drug treatments to the younger brothers of incarcerated individuals in order to determine if their physiological response was different than the general population—presuming a biological propensity for aggressive and criminal behavior (Washington 2006, 271–274). Although 1997 is long after the establishment of the requirement for IRB approval of all research on human subjects, scientists and doctors administered treatment to healthy children (who were predominantly black and brown) in order to study the presumed genetic or physiological basis of aggressive behavior.

Deep sequencing technologies have expanded exponentially since the original human genome was published. Scientists are again working to characterize human populations by genetic difference. Lawyer and scholar Dorothy Roberts argues that biologists (and the media) routinely use misunderstandings of race and identity based in social constructs that are easily refuted. Scientist have long sought to order populations according to their biology, with inherent value attached to various populations; Roberts (2011) clearly shows that this project continues.

Beyond work that explicitly studies race, bodies, genes, and health, some of the most important tools used in modern bioscience are literally built with black bodies. Take Henrietta Lacks, a black woman who was diagnosed with cervical cancer in the 1950s. Without her knowledge or consent, cells taken from her tumor became the first immortal human cell line and quickly were an essential research tool for cell biologists (Skloot 2010, 97–100), as they could be rapidly and continuously grown in laboratories (Skloot 2010, 40–41).

Art as an "Otherwise" Response to Biomedical Racism

Given the use of Western medicine and technology (roads, railroads) as tools for colonial projects, it has become increasingly necessary to imagine systems, indeed entire worlds, that are what scholar Ashon Crawley terms "otherwise." "Otherwise" movements are organic and community-based and do not rely on the systems (i.e., "rationality," existing infrastructure, "medicine") that placed us in our contemporary situation (Crawley 2015). Crawley uses "otherwise" in order to resist the notion of strategy and clear demands in movements against police brutality—being on the streets, fully inhabiting moments, performing in dance and protest, resisting facile or tired neoliberal "solutions." "Otherwise" movements organize and build without the necessity of clear and achievable goals.

Artistic expression can highlight, and perhaps even correct, the systemic inequity of the biomedical sciences and medicine. Leigh's work begins to eliminate boundaries between artistic expression, community engagement, performance, and bodily care. How "irrational," how "otherwise." But this may be precisely the type of confusing and confounding work required to create an "otherwise" world wherein embodied health care is no longer limited by the intersections of our identities.

Art/Science: A Pedagogical Enterprise

Science and the arts have long been in conversation. Before photographic imaging, an artist's hand was responsible for the dissemination of scientific images. The first widely published microscopic images, by Robert Hooke in 1655, were drawings—photography had not yet been developed. Early studies of the body and its motion similarly relied on artistic renderings. Contemporary art continues this tradition by repurposing scientific images, or by putting engineering and science, computers and/or programming, in conversation with bodies, motion, sound, and visual representation.

One major focus of contemporary art, which uses scientific images, foregrounds the dissemination of scientific understanding to a wider public. Here, the object is to demonstrate the beauty of science, and to explain how science creates and uses images. From art projects commissioned by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to reinforce the cultural and scientific importance of vaccination (2014), to the many artists who have painted with bacteria, which produce differently colored small molecules and therefore distinct hues (Ventura 2013), this type of work seeks to demystify science, to educate, to enlighten. Other projects, which represent biological images in glass sculpture (Jerram 2015), hand-cut paper sculpture (Howard 2015), or simply by reappropriating them for artistic purposes (Burel 2015), make the invisible (i.e., microscopic) visible and consumable as objects of art.

The science/art project Biocanvas has a mission statement that perfectly encapsulates these types of projects:

At Biocanvas, we think science is beautiful, and we think you should think so, too. Our mission is to provide a more approachable way for audiences to engage with science. By curating captivating science-as-art images, we hope to revitalize society's knowledge of and passion for scientific endeavors.

We know, we know. Science can be scary. And unfriendly. And impossible to understand. In fact, some people are so turned off by science that they ignore it altogether, regarding it as that biology class they barely passed in high school. But as scientists, we couldn't disagree more. Science is and should be human, vital, and accessible—not elitist, trivial, and unapproachable. (Burel 2015)

The difficulty nonspecialists have understanding scientific jargon can lead to issues with informed consent (Washington 2006; Skloot 2010; Holloway 2011). The general public remains largely unaware of the inner workings of science labs and how scientific knowledge is created, scientific images are constructed, and meaning is made from them (Latour and Woolgar 1979). At the same time, tax dollars paid by the general public finances the country's basic science enterprise. Therefore, the dissemination of scientific knowledge by artists is part of a democratic project that opens up the process of scientific knowledge creation to those who have provided the funding.

However, this type of artistic project also serves to reinforce the notion of scientific knowledge as objective; the historical and contemporary biases of science are masked. These projects remain primarily aesthetic; the power of race/class/gender/sexuality of and within the biomedical infrastructure remains invisible. This type of artistic enterprise might increase the popular understanding of science, but it serves to reify the status quo of scientific research.

Another tradition in art challenges the hegemony of scientific knowledge and seeks both to uncover the injustice and to proffer solutions or alternative modes of being in the world. Simone Leigh's installation is situated in this tradition. As a social practice installation that offers bodily care and centers the geography of health deserts and the history of biomedical violence, this work is developing a new artistic praxis that not only illuminates power and violence, but that also provides an intervention.

The biomedical sciences changed profoundly in the 1980s and 1990s. The emergence of modern molecular biology increased the amount of information we have about living systems and opened up new fields of investigation in biology. In this same period, the HIV/AIDS crisis also profoundly altered the way we understood our bodies, sex and sexuality, and disease. Urban centers were hard hit early in the epidemic. Out of this violence and massive death a rapidly evolving activist and artist movement arose to protest institutional silence, particularly in the government (Gould 2009; France 2012; Hubbard 2012). HIV activists viewed science as an institution treating them with violent neglect, but also as a source of hope (Gould 2009; France 2012; Hubbard 2012). A functional cure for those infected would come from research labs and doctors.

Art made by those affected by the HIV/AIDS crisis explicitly critiqued the medical, biomedical infrastructure, as well as the governmental funding agencies. A now famous ACT UP poster from 1987 shows then-President Ronald Reagan against a bright yellow background, his eyes pink, and his image covered with the words "AIDSGATE." The text is explicitly intersectional; it names the fact that more than half of the HIV positive people in New York City were Black or Hispanic and called the disease (and the institutional silence with which it was met) a "genocide of non-whites, non-males, non-heterosexuals."

Including and also beyond these artistic interventions, HIV/AIDS activists (largely HIV-positive themselves or belonging to groups viewed as susceptible to HIV infection) filled the vacuum of scholarship left by scientific, medical, and governmental neglect (Hubbard 2012). Members of ACT UP collaborated to create treatment plans that served to drive government and scientific policy. They protested at the National Institutes of Health and the FDA (Hubbard 2012). The necessity of community action drove this extension of sites of scholarship. Lives were on the line; those affected had no choice but to become experts on their own health.

Recent artistic work has also sought to identify, publicize, and alter medical and biomedical injustice. Jordan Eagles, a New York City-based artist, grapples with the ban on blood donation by gay men. Since 1977 (before HIV had been identified), gay men have been unable to give blood despite the emergence of precise diagnostic tests that remove any HIV-infected blood from circulation (Bennett 2009; Hurley 2009). The growing scientific and medical consensus is that the blood ban does no good to public health (Caplan-Bricker 2013). Eagles took blood from nine HIV-negative gay men and used it to craft a sculpture. Viewers of the work can see themselves in a mirror through the blood. The blood could be used to treat and heal; instead, it is being used, Eagles argues, for a somewhat less meaningful performance. It's being used for art. Eagles ties his sculpture explicitly to political change, linking to a petition calling for an end to the discriminatory blood ban (Bennett 2009; Hurley 2009).

Eagles' project, not insignificantly, advocates for full inclusion in the medical infrastructure. But it does not reject neoliberal frameworks, nor does it place the conversation about "gay blood" in a larger historical or intersectional framework. Essentially, it seeks integration of (gay male) bodies into the larger biomedical apparatus, not fundamental shifts in how that apparatus functions. It protests a policy and not the inherent violence of the underlying system. This work, reined in by its narrow focus, does nothing to eliminate barriers to care that exist for queer bodies. It is fighting to allow queer bodies provide care for others.

Care-Giving As Artistic Praxis

But back to my walk, early fall, in Brooklyn. Back to Stuyvesant Mansion; back to Simone Leigh, whose Free People's Medical Clinic might, as an object of art, have been a failure by outside standards. Many of the people I saw wander in and out of the installation were confused; they didn't know where to look. Most of the time there was no public performance. The viewer's eye was not guided. It wasn't immediately clear if it was a site of art or of care.

The Free People's Medical Clinic places Leigh directly in conversation with Karla Holloway's work Private Bodies, Public Texts. Holloway's book speaks of the legal and bioethical policies that have made women and black people public subjects throughout American history; meanwhile, overt violence has forced much of black culture behind closed doors (Holloway 2011). Leigh blurred these boundaries; she had dancers and caregivers perform in public, many unannounced, like a yoga instructor practicing in the corner. They simply were present in the space alongside classes, appointments, attendants, and visitors. But the care she offered remained behind closed doors, with restricted access, in some cases, to communities at various intersections of identity. Thus, Leigh is making private culture public—through performance—and caring privately for bodies that have historically been read as public texts.

Black bodies continue to be disappeared by state violence; barriers to health care continue to exist. What hope can there be for community-based care that fights these deep historical and contemporary forces? Leigh's work, as a self-described "social practice project," is limited. It will end. Nonetheless, Leigh pushed back at the requirement for long-term sustainability in the confines of neoliberal expectation:

I think that we have already had a big impact in many people's lives, and I think that sustainability is a really inappropriate mandate to attach to an artwork because there are so many things involved in an artwork that are intangible. As soon as I hear the word sustainability, I start to think about funders, and they then start creating benchmarks, and then they want evidence, and then they want a graph. (Osmundson 2014)

How "otherwise." One cannot escape a capitalist model, even under the guise of philanthropy or art. Many funding agencies want tangible, quantifiable results. Self-care may never fit this model.

Biomedical Reparations

Journalist and writer Ta-Nehisi Coates recently wrote a widely discussed article for the Atlantic, wherein he uses the history of housing discrimination to bring the discussion of reparations back into public dialogue. Discrimination had real, material consequences for black wealth; that state-sponsored discrimination, he argues, warrants financial restitution (Coates 2014). American medical science is built on the black body; this violence, like housing discrimination, was state sponsored, through the use of black bodies as literal material for experimentation as allowed by slavery or through state-funded research.

What might biomedical reparations look like? When considered in recent public scholarship, the idea of biomedical reparations tends to be considered as remedy for specific torts, as in the case of Henrietta Lacks (Palmer 2010), but what of the black victims of medical research and the health deserts in low-income neighborhoods? What of eugenics research, the connection between black and brown poverty and the development of the birth control pill?

Biomedical reparations (beyond the deeply systemic changes that would include free, single-payer health care and the installation of high-quality care centers in urban health deserts) might look something like Leigh's installation: a health center offering preventative and primary care, health education and movement classes, but without the neoliberal requirements to appease funders—no graphs to chart or metrics to meet. It might begin outside of existing systems of medical power. It might begin as embodied art, which may have much to contribute to correct the violent medicine of the past.

Conclusions

Nelson, Washington, Skloot, Leigh, uncovered hidden histories. Leigh deserves to be placed within this context. Coming into Stuyvesant Mansion was a bit like opening a book of scholarship, just not on the first page. The story was not linear, and not equally legible to all. Leigh's work may be most legible to those who lived in the neighborhood, and thus experienced the need, asking the rest of us to catch up.

The stories highlighted by these scholars, that Leigh put into practice, have been not only untold, but actively hidden by the state and by the academy. It has taken community memory and community work, alongside that of artists and historians, to tell these stories more widely. These are histories hidden in plain sight, literally written in and on every body on this planet. If you've had the polio vaccine, your body is built on that of Henrietta Lacks. If you have had a surgical suture without infection, your body is held together by the slave women of James Marion Sims. All bodies are built on black bodies.

When it comes to black bodies and health, our systems have utterly failed. The scholarship cited above, demonstrating the hidden histories of anti-black medical violence, was largely produced by scholars outside traditional fields of science and medical ethics. Washington is a social worker, Skloot a journalist, Roberts trained in law, and Leigh is an artist. They all filled a void and produced work that challenges violent status quos. In the face of systemic violence, we ought not to rely upon systems to save us. Those of us present and able, including doctors and scientists, artists and scholars, across identities and positionalities, must continue the long tradition of saving ourselves. We must reject the constraints of neoliberal rationality. We must care for ourselves and each other, and imagine systems—from a single clinic offering free yoga to single-payer healthcare—that cannot but do the same. We must use our own bodies, while we have them, to build our world "otherwise."

Notes1 Because Stuyvesant Mansion already offered doula services and ob-gyn care, there was insurance for those services.

Work Cited

Bennett, Jeffrey A. 2009. Banning Queer Blood: Rhetorics of Citizenship, Contagion, and Resistance. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press.

Benson, Barbara. 2014. "Interfaith Medical Center Files Plan to Exit Bankruptcy," Crain's New York Business. http://www.crainsnewyork.com/article/20140326/HEALTH_CARE/140329916/interfaith-medical-center-files-plan-to-exit-bankruptcy.

Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. 2014. "The Art of Saving a Life," Accessed July 23, 2015. http://artofsavingalife.com/.

Burel, Michael. 2015. "Biocanvas," Accessed August 15, 2015. http://biocanvas.net/about.

Caplan-Bricker, Nora. 2013. "The AMA Says Gay Men Should Be Able to Give Blood—But the FDA Isn't Listening," New Republic. https://newrepublic.com/article/113572/ama-says-gay-men-should-be-able-give-blood-fda-isnt-li.

Coates, Ta-Nehisi. 2014. "The Case for Reparations," The Atlantic. http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2014/06/the-case-for-reparations/361631/.

Crawley, Ashon. 2015. "Otherwise Movements," The New Inquiry. http://thenewinquiry.com/essays/otherwise-movements/.

Creative Time. 2014. "Medicine: Simone Leigh in Collaboration with Stuyvesant Mansion," Accessed July 23, 2015. http://creativetime.org/projects/black-radical-brooklyn/artists/simone-leigh/ .

Crenshaw, Kimberle. 1991. "Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence Against Women of Color," Stanford Law Review 43 (6): 1241–1299.

Farmer, Paul. 1999. Infections and Inequalities: The Modern Plagues. Berkeley: University of California Press.

———. 2003. Pathologies of Power: Health, Human Rights, and the New War on the Poor. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Flynn, Kerry. 2015. "Overdose of Hepatitis A Vaccine Given to 250 Immigrant Children Detained in Texas: Report," International Business Times. http://www.ibtimes.com/overdose-hepatitis-vaccine-given-250-immigrant-children-detained-texas-report-1996169.

Foucault, Michel. 1990. The History of Sexuality. Vol. 1, An Introduction. New York: Vintage.

France, David. 2012. How to Survive A Plague. New York: Sundance Selects, film.

Gould, Deborah B. 2009. Moving Politics: Emotion and ACT UP's Fight against AIDS. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Holloway, Karla F. C. 2011. Private Bodies, Public Texts: Race, Gender, and a Cultural Bioethics. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Howard, Jacqueline. 2015. "Hand-Cut Paper Sculpture Makes Microbes Look Breathtakingly Beautiful," Accessed July 23, 2015. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2015/04/10/cut-microbe-photos_n_7037972.html.

Hubbard, Jim. 2012. United in Anger: A History of ACT UP. New York: Jim Hubbard and Sarah Schulman, film.

Hurley, Richard. 2009. "Bad Blood: Gay Men and Blood Donation," BMJ 338: b779.

Jerram, Luke. 2015. "Glass Microbiology," Accessed July 23, 2015. http://www.lukejerram.com/glass/about.

Latour, Bruno, and Steve Woolgar. 1979. Laboratory Life:The Construction of Scientific Facts. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications.

Nelson, Alondra. 2011. Body and Soul: The Black Panther Party and the Fight against Medical Discrimination. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

———. 2016. The Social Life of DNA: Race, Reparations, and Reconciliation After the Genome. Boston: Beacon Press.

Osmundson, Joe. 2014. "How Many Black Histories We Still Don't Know: An Interview with Simone Leigh," Accessed July 23, 2015. http://www.thefeministwire.com/2014/10/many-black-histories-still-dont-know-interview-simone-leigh/.

Palmer, Larry I. 2010. "Private Reparations," Hastings Center Report 40 (6): 49.

Ridley, David B., Henry G. Grabowski, and Jeffrey L. Moe. 2006. "Developing Drugs for Developing Countries," Health Affairs 25 (2): 313–324.

Roberts, Dorothy. 1997. Killing the Black Body. New York: Vintage Books.

———. 2011. Fatal Invention. New York: The New Press.

Skloot, Rebecca. 2010. The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks. New York: Broadway Books.

Spellen, Suzanne (aka Montrose Morris). 2011. "Stuyvesant Heights Mansion: Under the Big Tent, Part 3," Accessed December 23, 2016. http://www.brownstoner.com/blog/2011/02/walkabout-under-2/.

Stein, Rob. 2015. "A Controversial Rewrite for Rules to Protect Humans in Experiments," Accessed January 20, 2016. http://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2015/11/25/456496612/a-controversial-rewrite-for-rules-to-protect-humans-in-experiments.

Thompson, Nato, Rashida Bumbray, and Rylee Eterginoso. 2015. "Curatorial Statement," Accessed July 23, 2015. http://creativetime.org/projects/black-radical-brooklyn/curatorial-statement/.

Ventura, Anya. 2013. "Painting with Bacteria," Accessed July 23, 2015. http://arts.mit.edu/painting-with-bacteria/.

Washington, Harriet A. 2006. Medical Apartheid. New York: Anchor.