Abstract

This “practice biography” of a participatory performance and anti-stigma classroom educational tool, Tracings of Trauma, illuminates the important role of emotion in intellectual work. It is rooted in interview data from Iraq and Afghanistan combat veterans and illustrates how artistic translations of research provide social scientists ways to contemplate their work subjectively. Beyond benefits to the researcher, these translations can flow into the emotional landscape of audiences in ways that encourage reflection. This practice of transforming emotion and judgment into artistic products connects us more deeply to the people we work with and can be applied in ways that are relevant and accessible to those who help to produce the findings. The public practice of these interventions in our broader communities produces social change in ways that often escape traditional academic forms of dissemination."At first you don't want to put this burden on anyone but then you get to a point where war manifests in such terrible ways that you question, 'why should I carry all of it?' "—Iraq Combat Veteran, Army

The cross-fertilization between art and science gives birth to interesting forms of disseminating data that connect us to new audiences, but also allow for rapid change in the communities in which we work. This "practice biography" looks at the evolution of one of these forms and the role of emotion in scholarship. It traces my experience as an anthropologist doing research with Iraq and Afghanistan veterans and my growing responsibility to the participants I work with to share the burden of war with the public through non-academic mediums.

I will argue that arts-based scholarship offers many opportunities for anthropologists and other social science scholars to develop a public practice that moves us. It moves us to connect on deeper levels with our participants and forges better relationships with them. Most importantly, it generates a knowledge production that is meaningful to the people we work with. These products can teach about social and cultural difference in a manner that nurtures empathy and compassion—the very social experiences that connect us as humans. Artistic translations of our research provide us ways to reflect on our work subjectively in a world of "objective" science. In unpredictable and rapid ways, artistic translations of research can inspire and contribute to promoting interpersonal social justices that bounded academic projects often miss out on.

This opportunity to quickly share research in nontraditional ways allows for a speed of production that is important to the communities in which we work. My project allowed me to share data in a way that was relevant to the immediate needs of veterans to feel understood and accepted in society. When we work in social settings where people are struggling, quick reaction attests to our compassion and commitment. This is important in an academic world where our research products may take up to 10 years to come to fruition.

I use the term "practice biography" deliberately. It describes the development of my own personal and professional practice of emotional awareness and the incorporation of this awareness into research and its products. This article follows the evolution of oral history into public performance and then into classroom practice. The products, a creative monograph, an interactive performance, and an educational tool, grew out of raw interview data from my doctoral research. In response to veterans' stories of social disconnection and their desire to be understood, the purpose of these products is to reduce mental health-related stigma surrounding trauma and war.

The educational tool teaches professionals and students in the social services and the health services about the multiple perspectives that make up the veteran experience. The design and content encourages learners to critically engage in issues surrounding cultural values, self-reflection, and the impact assumptions have on our personal and professional lives.

Surplus Data: The Personal Practice

As scholars of everyday experience, anthropologists are interested in the logic behind people's behavior and their belief systems. We are interested in "why people do what they do" and the sociocultural, political, and economic factors that shape these activities. As the pioneering cultural anthropologist Ruth Benedict was purported to have said, the central mission of anthropology is ". . . to make the world safe for human difference."

But academic writing can be a very disengaged and one-dimensional vehicle for this important task of creating understanding of others. Specialized research is typically only accessible to a small group of experts to learn from, discuss, and advance. And yet ". . . anthropological texts address topic areas, and illuminate questions pertaining to the human condition, which are of burning importance to a great number of non-specialists" (Eriksen 2006, 94).

For those anthropologists and social scientists working closely within the community, traditional scholarship does not easily allow for this integration of public and professional practice, at least not in a way that contributes to professional advancement and tenure. Nor does it acknowledge the huge amount of emotional investment that accompanies this type of work.

With very little room for the emotional, known in anthropology as "surplus data" (the nonintellectual part of research that emerges during fieldwork), we often end up compartmentalizing our work and the dissemination of our findings. For example, we publish ethnographies, but then we write separate memoirs about the visceral, spiritual, or psychological reactions the fieldwork created in us. Or, a journal is kept in order to monitor methodological decisions in the research process, why they were made, and with particular attention to a researcher's own values and changing interests. These journals are private and also viewed as a form of catharsis (Lincoln and Guba 1985). Rarely is the emotional space occupied by the researcher reported with the other findings, augmenting and nuancing them. This is disjointed, since emotions drive our own cognition and are what connect us as humans and to our work.

Physiologically, we do not separate and parcel out the emotional and cognitive in neatly organized processes or in distinct brain regions, they are integrated and provide dynamic interactions (Pessoa 2008). Research in neuroscience suggests that this false and unproductive split implies that intuition and feeling as an inferior form of knowledge. According to neurologist Antonio Damasio, ". . . feelings are just as cognitive as any other perceptual image. . . . But because of their inextricable ties to the body, they come first in development and retain a primacy that subtly pervades our mental life" (2005, 159).

This makes emotions highly influential in cognitive processing and very important because they color our thinking and interpretations. McLaughlin (an educator) in "The Feeling of Finding Out" (2003, 67) discusses Abercrombie's The Anatomy of Judgment (1989) and illustrates how the actions of perceiving, judging, and emoting are intricately connected when we are interacting with others. In anthropology, distinctions between sensing and intellect are challenged through the notion of "embodiment," where "on the level of perception it is not legitimate to distinguish mind and body" (Csordas 1990, 36). Ethnographic work is "embodied" and explains how researchers learn and know through a constellation of sensory, or bodily, experiences. Emotional states of being therefore enable our interpretations when treated with the same importance and methodological rigor as other empirical work (Spencer 2010).

Each of us feels our work: we get excited when an idea generates, we feel thrilled when it is shared, and dejected when it is dead in the water. More importantly though, we feel the people we are collecting data from. We feel proud when someone has their first-year anniversary of sobriety, we get angry when someone does not get the social services they need, and defeated when that person commits suicide. Certainly, it is the constellation of these emotional reactions that, on one end of the continuum, motivates us and on the other, crushes us.

In studying the lives of ten veterans returning home from Iraq and Afghanistan, I fielded a lot of emotions—theirs and mine. At times, my objectivity and judgment were challenged by the profound emotional reactions I experienced in hearing their stories of war, trauma, and readjustment to the civilian world.

Following their psychological and spiritual transitions from "heroic" fighter to "mentally disordered" civilian, I embodied their traumatic memories, even though I was barely brushing up against them. This was confusing and messy. I interpreted my embodied reaction as empathy in action. As a witness to their trauma, I cannot say I was traumatized myself. For me, this undermines veterans' experiences and perpetuates their silence (many do not open up to family and friends for fear of burdening them with their pain). Since suffering is part of the shared human condition, I could feel the pain of the veterans through my own life history. Although the degree and circumstances of that pain was certainly different, I was able to keep listening. This is what mattered most.

I did feel things I had a hard time acknowledging. Sometimes, it was a physical reaction—a sinking feeling, a tightness in my chest, a lump in my throat, a racing heart. The thoughts attached to those feelings were guilt, anger, betrayal, and anxiety, but also awe.

My guilt was the shame I felt regarding my life's challenges and frustrations, or what one veteran called "first world problems." This guilt helped me understand why veterans felt like they could not relate to their civilian counterparts who had not made similar sacrifices to serve, or endure the deprivation of war zones. I was in awe that people could survive such horrors and go on with their daily lives: working security at the state fair, sitting in a World War II history class, going to their kid's baseball game, or listening to their friends complain about how slow their Internet is.

As I was trying to make analytical sense of my research, I was also working through my own reactions to stories of racism, deliberate violence, unrequited sacrifice, and military propaganda. All these reactions, as my advisor would say, are important because they are a reflection of the broader cultural beliefs in my community. But they were unsettling. And, admittedly, I was sometimes intolerant of the veterans I worked with.

I felt some were ignorant to assume the military had their best interests in mind or that our government had the world's best interests in mind. I also felt that some veterans felt entitled to accolades or special consideration for their work, when they had voluntarily signed up to do a job. Other veterans assumed that all civilians were "clueless" and could never understand what sacrifice meant. And here I am, the daughter and granddaughter of a generation of Dutch civilians who suffered through the Nazi occupation, World War II, and its aftermath. Growing up I was often reminded of what war is and does to people—the collateral sacrifice. It was through participation in the Veterans Book Project that I was able to make sense of these emotions, and also to use my surplus data in a way that lent itself to a product that benefitted the veterans I worked with.

Objects for Deployment: Making the Personal Public

The Veterans Book Project is a collection of short creative monographs that reconstruct the memories of people who were affected by the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. The books are collaboratively authored with artist Monica Haller. Some of the books are compilations of drawings, some are textual, while others are repositories of photos and collages. As a collection, these Objects for Deployment have traveled all over the country to be shared and to educate about the impact of war across diverse groups of people. Monica and I connected on a very raw level in that we both were engaged in stories of others' trauma and wanted to do something constructive with these experiences.

Writing a monograph (Hooyer 2013) for this project forced me to address my research in an intimate way and offered me a first pass at thinking about my interviews with veterans in a nonintellectual manner. In this stage of initial fertilization between art and scholarship, I was able to process my emotions in a manner that did not compartmentalize "feelings" and "facts."

Monica helped me to identify the key themes of my experience and ways to express them that crossed the analytical confines I worked within. These confines were the scholarly expectations of writing a dissertation and of theorizing veterans' suffering in a way that felt disconnected and dehumanizing. Dehumanizing, in that I had to analyze veterans' experiences and translate them into social science concepts. These analytical concepts were meaningless to those very veterans who were sharing their most intense, life-changing memories with me. This professional practice felt far removed from my unprocessed anger, empathy, and urgency. Creating a monograph that moved outside of the bounded requirements of academia was a step in my emotional sense-making.

In my research with veterans, I bore witness to horrific experiences that challenge our deepest understanding of what it is to be human. But I wanted to do more than bear witness. I wanted to engage the public in bearing some of the burden of war. As a medical anthropologist, I am immersed in a landscape of social suffering. I also am obliged to critically reflect on the impact that the descriptions I present have on the general public. Profoundly influenced by the critiques of Nancy Schepher-Hughes and Philippe Bourgois, I was activated to question:

What do we want from our audience? To shock? To evoke pity? To create new forms of totalizing narrative through an "aesthetic" of misery? What of the people whose suffering is being made into a public spectacle for the sake of the theoretical argument? (Schepher-Hughes and Bourgois 2003, 26)

I did not want to sensationalize the lives of these veterans, nor leave the reader in a state of despair. By design, I had to create a human connection between the veterans whose prose I used in the book and my civilian audience. I needed to offer an opportunity for a shared human experience that could promote an understanding of war trauma. That is what I wanted from the audience and that is what the veterans desired from society. Here is where the artist, Monica Haller, and myself, the scholar, cross-pollinated our ideas.

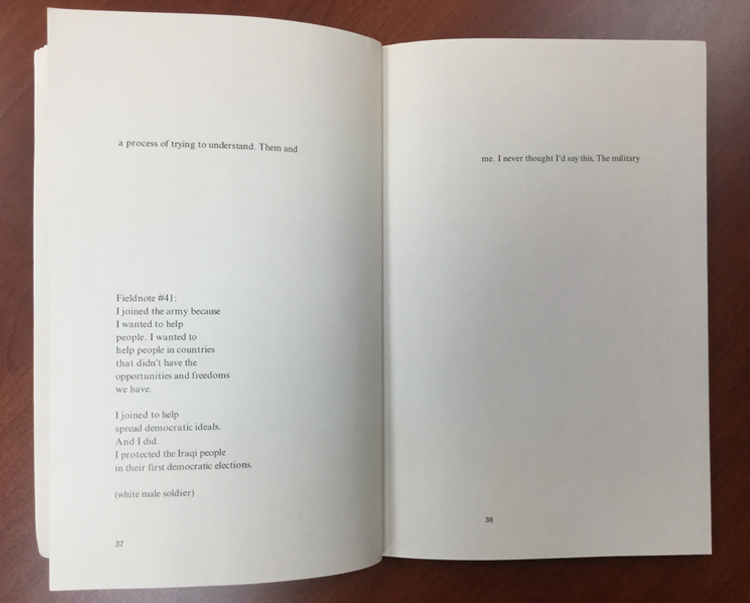

Monica helped me to visualize my feelings and professional ethical concerns as more than paragraphs of text on paper. I wanted to weave my experience with that of the veterans, intertwining our voices in a manner that would reflect my changing emotional landscape and its impact on my politics. As a civilian, it was reasonable to expect that my reactions to veterans' stories were similar to other civilians in society, who were so far removed from the cost of war. To present this visually, my meta-narrative runs across the top of all pages in a single line and the field notes from veterans' interviews are placed below, as prose.

This pattern, juxtaposing the veterans' words via field notes and my words via meta-narrative, spoke to the need to move back and forth between my emotional reactions and the "facts" of my work in order to accurately represent others' experiences. The design also highlighted how the deliberate and constant comparison of my ideas and the multiple perspectives of the veterans brought about new understanding.

This reflective approach is integral to the design process behind anthropological knowing. Anthropologists work to understand the meaning of peoples' experience, ideas, and practices in expansive ways. This involves spending extended amounts of time with research participants, immersing oneself in their lives. It includes all the complexity and messiness that accompanies personal relationships, especially learning the most appropriate ways of interacting. This is critical to building trust with the people we want to understand. Anthropological knowledge is "situated," meaning it exists inseparable from context, activity, beliefs, people, culture, and language. Reflecting on our internal emotional and cognitive state is necessary in order to systematically and rigorously interrogate the preconceptions, political views, and feelings that influence our interpretations.

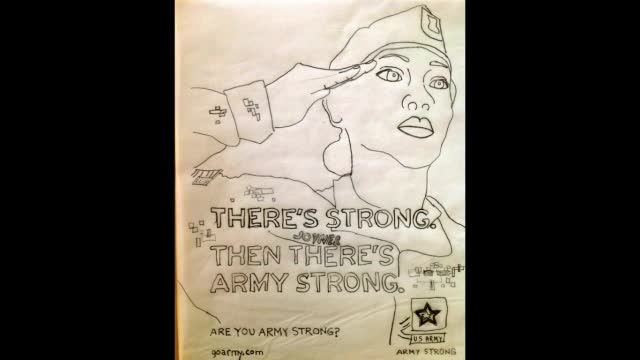

To process my experience in a nonintellectual way, I decided to trace some of the photos of military service and deployment that my veteran participants shared with me during interviews. Tracing the photos allowed me to stop thinking and to experience the content differently.

This video clip shows some of the tracings that I made of veterans' photos. Courtesy of the author.

The amount of time and detail the tracings required allowed me to get closer to veterans' experiences more slowly and with more time to respond. Rather than talk, I traced. Rather than think, I imagined. Rather than struggle to find the right words to describe a photo I could not publish, I traced it and I imagined what it was like, for example, to be in Iraq, riding in a tank. Or to be in the immense heat of the desert in full gear, carrying heavy weapons, dragging a 70-pound rucksack on my back. I imagined what it was like sharing candy with kids who wanted to play, but in other contexts might be burying roadside bombs with the intention to kill me.

In some ways this kinesthetic practice offered my brain some respite from writing and analyzing. But looking at the photos also allowed me to make connections that were difficult for me to understand and accept. I saw and felt some of the happy moments, the positive experiences of being deployed: the camaraderie, the pride in helping people, the esteem of surviving hardship and the feeling of accomplishment that "I did this, I made it." In some ways, words undermined and corrupted these feelings because they contradicted the dominant narratives of war.

This practice of tracing, and then connecting the feelings that emerged to the stories veterans shared with me gave me a fuller picture of military service. In fact, it brought up emotions in me that were unexpected, specifically my perplexed feeling of envy. The mutual devotion, honor, trust, unconditional support and love that veterans expressed for their battle buddies was something I had longed for in my life. The irony lies in the hostile and horrific ordeals that brought about these feelings of peace and love for these veterans.

My Object of Deployment piece for the Veteran Book Project, offered me a vehicle to express my humility, empathy, confusion, and respect, but also to reflect on my changing politics. It allowed me to do this in a way that resonated with the veterans participating in my study. It resonated because, in a small way, I was able to mirror the very experiences they were having with other civilians in their lives. Significantly, the veterans with whom I shared my monograph inspired the real transformation of this monograph into a public practice.

Tracings of Trauma: The Public Practice

"The military, they don't un-train us. And then we get home and we don't fit in. We come home and we are strangers. You feel really lost. You feel you don't belong anymore. That is not a disorder. I want civilians to know this."—Nikki, Iraq Veteran, Army

For the veterans I interviewed, one of the most important things they wanted to convey to the public was that veterans of war are changed persons; they did not ask for this trauma and the consequences of their military experiences are not their fault. They felt they did their job to "protect and defend" and "answered the call to serve" the country in a time of crisis and now felt that the civilian population, in general, was apathetic or worse, blaming them for the "veteran problem." This lack of compassion and empathy, from the veterans' point of view, really informed my choice to further develop a public practice.

After the publication of my Objects for Deployment monograph, I showed it to the veterans whose narrative excerpts I included in the book. To see the pride and satisfaction in their faces as they read their own words and saw tracings of their photos in print, and for them to consider how sharing their personal stories could contribute to some change in public perception, was beautiful to me. I witnessed a small transformation that suggested this work could make a difference for the veterans sharing these difficult stories. Veterans expressed feelings of catharsis and acknowledgement as they remembered the interviews and saw their words on paper. Knowing that this book would be available free to read online and that it would travel across the country in art exhibitions for major institutions, they recognized the impact their voices could have in broader social discussions of the moral cost of war. Discussions that many did not want to openly have in a public forum, for fear of judgment and exposing their identity. More importantly, veterans felt the book validated their experience as individuals.

It was painfully apparent in that moment that the narrow scholarly project of publishing in journals provided little validation for my research participants. They wanted their voices to be heard and heard in a way that was meaningful to them. They were not going to email links to my journal articles to their families and friends. And they certainly were not going to pay $35 to read it.

These academic constraints inspired a collaborative, arts-based dissemination project. Art, I decided, was the way to despecialize this research and translate it for diverse audiences. Having the veterans' voices heard was the goal and sharing the burden of war was a main objective, but I did not want to distort or undermine their voices through my own interpretations and analyses.

I thought about how to do this both symbolically and literally. To frame this next iteration of the project, I adopted performance art scholar Rivka Eisner's theory of an "inherited wound of responsibility" (2012). In inheriting memory through story telling, Eisner emphasizes the need to differentiate between the wound of the teller (the survivor), and the wound of the listener (the secondary witness). The teller's wound is related to direct loss and personal experience and it is critical not to collapse this wound with that of the listener. Doing so can lead to "empathic over-identification" and apathy and an ". . . overt refusal of responsibility/answerability by secondary witnesses to individual, structural, or historical trauma" (Eisner 2012, 61). In Eisner's construction of the listener's wound, "The inherited wound of responsibility does not victimize, but rather inspires the witness to actively move toward increasing justice and just relations" (2012, 61). For me, this meant sharing veterans' lives with the public in a way that brought the public closer to veterans' stories of love and loss, and fostered a human connection that sparked understanding and empathy. I wanted the public to embody veterans' words and move them to brush up against the reality of war in a very personal way.

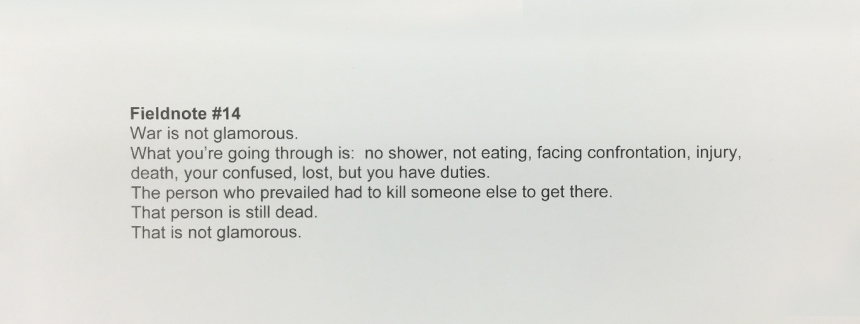

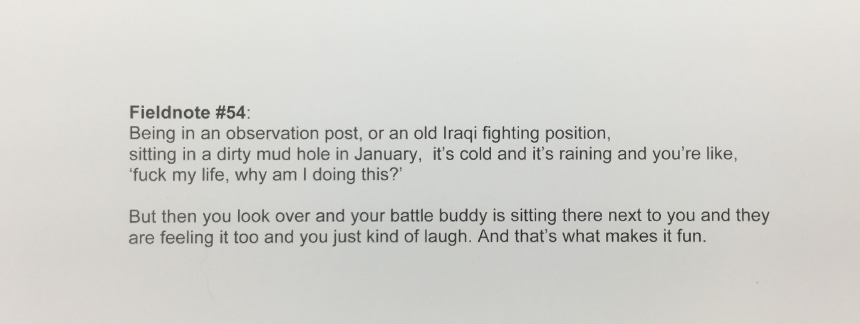

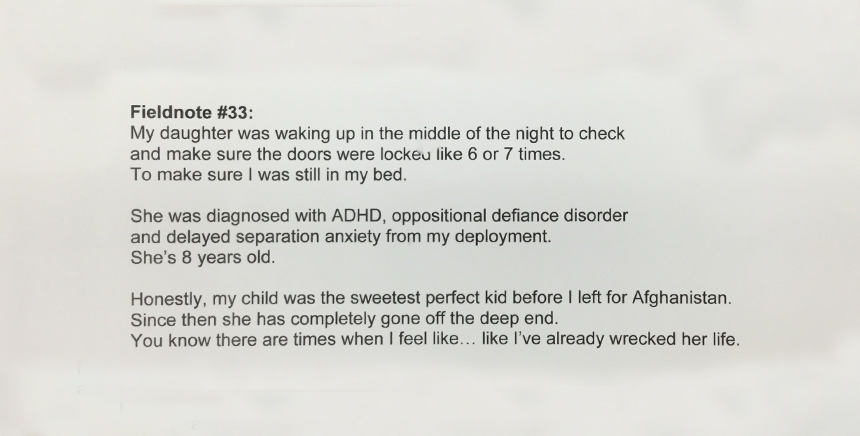

Applying Eisner's theory into practice, I transformed the book into an interactive performance. In this piece, I speak in my own voice and recount my experience as a civilian scholar collecting veterans' stories of war, and the audience speaks in the voices of the veterans I interviewed. Excerpts of veterans' interviews are printed on numbered "field notes" that are passed out to audience members.

As I tell my story, detailing my emotional responses to veterans' stories, I call out my field notes for participants to recite.

A short excerpt of a performance for a veterans' art exhibition from the film Almost Sunrise. © Thoughtful Robot Productions. https://vimeo.com/147204025

We interweave, sometimes blurring the boundaries of, the wounds of the teller and the wounds of the listener, especially when veterans or civilian survivors of other wars, such as Vietnam or Bosnia, are present in the audience.

Through this design, I strove to ensure that the audience takes on a "wound of responsibility" in representing the voices of veterans. The responsibility is deliberately articulated in the instructions for participants at the start of the performance: recite the words, without censoring them, in a respectful and sincere manner. The difficulty of this responsibility becomes apparent when audience members leave out words from field notes, and then I have to repeat them. For example, in one performance a woman did not recite the word "fun" in this field note from an Army soldier who was describing the camaraderie of collective misery.

When I spoke with her after the performance, she said, "I just couldn't say it, I couldn't say the word 'fun' in the same sentence as war. I didn't agree with it." She had been an anti-war activist during Vietnam and her politics were so strong they kept her from making the public statement that her field note represented. She felt she was betraying her politics in making that veteran's words public.

This speaks to the power of these words and the emotional reactions they invoke. But this is the whole point: To have civilians who do not understand military service acknowledge the seemingly contradictory ways of knowing war—through the sound of their own words spoken out loud for all to hear.

Creating New Observers

Anthropologist Michele Boyd, in her article "Good Tape: Methodological Lessons from Working in Audio," argues that sound is powerful because it ". . . activates listener's imaginations so that they are cocreating the experience with the producer" (2013). Importantly, the aural maintains expression and emotion in a manner that humanizes the experiences of marginalized people. This is the strength of recorded interview-based research. But as Boyd points out, social science knowledge often loses this power because the final product is typically written.

In performing my field experience with the public, we utilize the power of the aural and the oral. Participants recite and embody the words of veterans, but are encouraged to listen to what other participants are reciting and how these perspectives may differ from his or her own field note. Most importantly, the audience is directed to consider how their own experiences of love and loss emerge to foster a shared human experience with veterans.

The veterans' opinions, feelings, and actions are translated through the audience who are at once listeners and tellers. As tellers, the words (un)settle in their bodies. This is reflected in audience members who are moved to tears in reciting their field notes, or refuse to recite all or any part of them. Sometimes participants begin to speak more softly, slowly, or speed the tempo and increase the tone of their voice. Others will enunciate some words more than others, for emphasis. These small inflections and personal expressions can bring new meaning to a field note. Their translations become more personal as they layer their own experiences on top of those of the veterans who they are representing.

For example, the father who began crying as he recited the field note of an Army soldier talking about her daughter's intense anxiety and behavioral disorders. (See Fig. 8.) He, too, had an eight-year-old daughter. Or the Vietnam veteran who struggled with his field note to recite the words of a young Iraq vet, "I do not have PTSD, this is just who I am now." This man disclosed to the audience, after the performance, that he was 100% disabled—because of his PTSD. He took part in the performance as a gesture of support, embracing the words of a younger generation of war survivors. Even though this Vietnam veteran did not want to recite the first part of that field note, he did so out of respect to that Afghanistan veteran's experience.

In these ways, the audience challenges fundamental assumptions about social science knowledge production and dissemination. Who constructs knowledge? And who provides that data? Who controls the meaning? Who accesses it and how? Perhaps, most importantly, who benefits?

In constructing knowledge, the anthropologist as scholar is tasked to translate and accurately trace peoples' experiences. Yet with every translation, there is a change in meaning. Something gets "lost" or distorted in the anonymity of the participants and the researcher's reinterpretation, during the move from raw data to theoretical analysis. It could be seemingly small: a gesture, a nostalgic moment, or a facial expression. Or it could be something as profound as a deliberate political leak, a fading memory, or a secret confession.

The audience's voices, the meanings they create through this performance, challenge this notion of loss. Participants create meaning through comparing their experiences of love and suffering to those of veterans. The memories and disclosures of war and military service have a different effect on participants, depending on their own experience, as the examples of the anti-war activist, father, and Vietnam veteran above, suggest. It is the field notes that audience participants enact that create the biggest impact. This is reflected in the comments that people make after the performance. Some ask about a particular field note, or expand on how they felt reciting things they could never relate to. Others share their own stories of war, loss, and hope as a symbol of human connection and support to the veteran whose field note they read.

In this manner, the field notes in this performance are research ends, not just means. The knowledge is experiential and coproduced through the oral—the audience's voices—without my application of anthropological theory and philosophical analysis. These audience participants are not passive consumers of this social scientific knowledge, but active producers of its meanings. Their stunned pause, angry inflection, or break in tone—they all contribute to new and changing understandings of veterans' lives. The audience voices are a form of transformative meaning-making in that they filter veterans' experiences through their own personal, cultural, and historical biographies. In these biographies, they have all experienced suffering and happiness. When participants layer their own history with that of the veterans, emotional connections are made across wide gaps in experience. Taking responsibility to enact another person's words, an audience member momentarily sees the world through that veteran's eyes. The audience comes to know these veterans in a new way.

And in a way that escapes traditional academic writing, this enactment validates veterans' experiences of trauma, war, and reintegration. This is a healing moment for veterans in the audience, specifically for those who come with family and friends. As one Army veteran told me, it feels safer when strangers voice your feelings; no one knows they are your words, but "people are listening" and they are "thinking about what they are hearing." The fear of judgment is removed. Another veteran expressed his discomfort in hearing his own opinions, but that it was the only way others could learn about life after war. He was grateful to be part of that message, and wanted to help in future iterations of the project. Other vets offered suggestions and connections to "get the word out," referring me to leadership at Veterans Affairs and community agencies.

In a small but unique way, enacting veterans' voices gives civilian friends and family the opportunity to express empathy in a structured format. One family member told me the performance will help her better support her boyfriend when he comes home; he is a Marine and currently deployed. Another woman expressed that listening to the field notes gave her the confidence to talk to her friend, an Iraq veteran, about his deployment. Most significant for me, was the comment of a civilian, with no connection to any veterans, who said, "No wonder these guys feel so detached."

This empathic understanding is what veterans who collaborated on this project wanted from this performance. Witnessing the willingness of an audience to listen to, and to embody their individual and collective words, veterans' desire to be heard was validated. This comfort is a first step in social healing.

The Pedagogical Tool: Back to Professional Practice

Through the eyes of the veterans I collaborate with, the effectiveness of my research is measured through the positive changes in veterans' lives. What they want is a more understanding and empathetic community they can come home to and reestablish in.

In the world of academia, my research is peer-reviewed by experts in trauma studies, health services research, and medical anthropology. Impact is measured by the amount of articles published, the number of times these articles are cited by other researchers, and the types of journals one publishes in (e.g., journals with high "impact factor" ratings). So how do social science researchers turn arts-based dissemination into scholarship? How do I regenerate this performance into something that "counts" towards my professional goals, while staying true to my veteran collaborators and their goals?

As a postdoctoral fellow in academic primary-care research, I have learned that projects that are codesigned with the community are a form of nontraditional scholarship.

Developing a pedagogical tool for the community, documenting the process, evaluating the outcomes, and submitting these products for peer review constitutes scholarship.

With the support of my mentors and the veterans I work with, I have turned Tracings of Trauma from a public performance into an educational tool for health service providers and researchers-in-training. Since military service has such a profound effect on the women and men who serve, giving them unique perspectives on life, service providers need to be aware of these nuances. Tracings of Trauma aims at teaching about these perspectives and through taking part in reciting narratives from the script, the audience gains a partial experiential understanding of veterans.

The objectives are threefold. First, as a pedagogical tool, the performance encourages students to critically engage in issues surrounding cultural difference. Deliberately, and with the input from veterans, the piece is intended to reduce mental health-related stigmas around veterans and PTSD. Second, the project promotes competencies around self-reflection, empathy, cultural values, and compassion. Specifically, the project speaks to the need to acknowledge and manage personal values in a way that allows professional ethics to guide practice. And third, as an immersive multimedia experience, this performance allows for different ways of learning and knowing, crossing disciplinary boundaries. This provides opportunities for dialogue between students from different social science, humanities, and health science fields to come together on veterans' issues.

Performing parts of veterans' experiences through collaboration between the anthropologist and these diverse audiences provides for a range of expressions and interpretations. This helps to identify various veteran and civilian subjectivities, but also exposes the common themes that connect us all on a human level. Currently, Tracings of Trauma is offered as a session for medical, social work, nursing, and occupational therapy students. It is also a session I present at conferences where practicing health providers can earn continuing medical education credits.

Emotional Data and Public Transformations

The role of emotions as data is rooted in a history of anthropological argument and feminist critique (the "writing culture" debates) and in the last decade scholars from other disciplines have called for more attention to the influence of emotion on research activity. The breadth of this literature is beyond this discussion, but I want to highlight some of this work and provide some historical context to situate this "practice biography" of Tracings of Trauma.

Before the idea of embodiment was conceptualized in anthropology, in relation to emotions as a way of knowing things, the "writing culture" debates in the 1980s illuminated the position of the researcher (e.g., status, gender, ethnicity) in representing others and producing knowledge. Out of this debate came a series of essays entitled Women Writing Culture, edited by Ruth Behar and Deborah Gordon (1997), that refused to separate the personal from the political, introducing new approaches to feminist, critical, and creative writing. Immediately prior to this, in Behar's groundbreaking book, The Vulnerable Observer: Anthropology That Breaks Your Heart (1996), the author's personal voice was used to interweave memories with her fieldwork, provocatively illustrating how the researcher is emotionally situated in ethnographic work. The book I wrote for The Veterans Book Project, Surplus Data, reflects this approach.

More recently, the volume Emotions in the Field (Davies and Spencer 2010) picks up where these earlier culture debates left off. Emotions, as everyday and common occurrences, are brought into the analytical domain for radical, empirical reflection through each of the essays in this collection. The editors argue for a renewed understanding of reflexivity that earlier debates left under-investigated, one that calls for the careful translation of emotional data in knowledge construction. This reflexivity is critical in order to attend to the influence that strong emotions have on our data collection and the questions we ask, both obscuring and illuminating new inquiry (Levy 2016).

These reflexive sensibilities are mirrored within feminist studies' "emotionally engaged research" (Campbell 2001, 123) where research incorporates affect and cognition together in the study design and interpretation of data. In this process, researchers stay attuned to their own emotions and those of their participants, and emotions become an instrument for inquiry and data collection. As a method, these feelings are woven ". . . into the analysis so that these findings and experiences are absorbed as part of the larger project instead of being treated as separate . . ." (Blakey 2007, 4).

In researching emotionally charged topics (e.g., rape, trauma, natural disaster, political revolutions), researchers frequently end up attuning their emotions to those of their participants, shaping the research in new ways. In Blakey's (2007) "Reflections on the Role of Emotions in Feminist Research," she illustrates how emotionally engaged research is guided by an ethic of care. This involves caring for the research topic, the participants, what happens with the data (the emerging narrative), the researcher herself or himself, and the research team. For Blakey, this ethic of caring allows space for new questions and interpretations, and exposes positivist illusions of objectivity and value neutrality in research.

This is echoed in the emerging field of sensory ethnography, where anthropologists have further illustrated how their embodied experiences have helped them interpret others' worlds (e.g., Stoller 1997); knowledge-making is a shared experience influenced by broader environmental factors (e.g., Marchand 2010); and learning through bodily practices helps us "come closer to understanding how other people experience, remember, and imagine" (Pink 2015, 25).

From this abbreviated discussion, we can surmise that the lens these scholars see through is not only influenced by their cultural and historical biographies, but also by their own emotional states and how they arise relationally. The focus is on the researcher. But what of the embodied experiences of those "others" that interact with our research? Especially for those of us involved in participatory and community engaged research? This is what I am exploring through this interactive, arts-based translation of research.

While I have illustrated much of the same arguments for the role of emotion in research discussed above, I am suggesting a more deliberate analysis of the impact of emotions and reflexivity on our audiences and our research participants. This is a relational process that allows our audience to get closer to the researcher and his or her practice, humanizes research, and allows for a wider range of interpretations and connections. Additionally, it nudges the audience to reflect in a public space and promotes shared knowledge-making.

What Tracings of Trauma and other arts-based interactive works do is translate research in a way that expands embodied understanding beyond the field researcher to a new set of participants. Performing parts of veterans' experience through collaboration between diverse audiences and myself provides for a range of expressions and interpretations. This helps to identify various veteran and civilian subjectivities, but also exposes common themes that connect us on a human level: fear, love, loss, hope, and pride. Translating my findings into a performance piece allows for these new interpretations to be created and used by the public for sense-making.

Tracings of Trauma allows the audiences to have deeper, more meaningful connections with veterans, offering comfort in moments that were previously empty or awkward. The project provides a vehicle for community-based knowledge production and also allows me to express my gratitude to veterans. In unique ways, it offers audiences a way to consider their own "surplus data" in their everyday encounters with others.

Acknowledgments

Heartfelt thanks to Zeno Franco for the critical nudging and conversations that directed my thinking on this piece, and to Monica Haller of the Veterans Book Project for incubating my ideas early on. I am so grateful for the Department of Family and Community Medicine, Medical College of Wisconsin, in supporting my path towards arts-based scholarship in academic medicine. This article was made possible by Grant Number T32 HP10030 from the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), an operating division of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the author and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Health Resources and Services Administration or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Work Cited

Abercrombie, M. L. J. 1989. The Anatomy of Judgment. London: Free Association Books.

Behar, Ruth. 1996. The Vu lnerable Observer: Anthropology That Breaks Your Heart. Boston: Beacon Press.

Behar, Ruth, and Deborah A. Gordon, eds. 1995. Women Writing Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Blakey, Kristin. 2007. "Reflections on the Role of Emotion in Feminist Research," International Journal of Qualitative Methods 6 (2). Accessed February 12, 2016. https://www.ualberta.ca/~iiqm/backissues/6_2/blakely.htm.

Boyd, Michelle. 2013. "Good Tape: Methodological Lessons from Working in Audio," Public: A Journal of Imagining America 2 (1). Accessed August 2, 2015. http://public.imaginingamerica.org/blog/article/good-tape-methodological-lessons-from-working-in-audio/.

Campbell, Rebecca. 2002. Emotionally Involved: The Impact of Researching Rape. New York: Routledge.

Csordas, Thomas J. 1990. "Embodiment As a Paradigm for Anthropology," Ethos 18 (1): 5–47.

Damasio, Antonio. 2005. Descartes' Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain. New York: Penguin Books.

Davies, James, and Dimitrina Spencer, eds. 2010. Emotions in the Field: The Psychology and Anthropology of Fieldwork Experience. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Eisner, Rivka Syd. 2012. "Performing Pain-Taking and Ghostly Remembering in Vietnam," The Drama Review 56 (3): 58–81.

Eriksen, Thomas Hyland. 2006. Engaging Anthropology: The Case for a Public Presence. Oxford: Berg Publishers.

Hooyer, Katinka. 2013. Katinka Hooyer. Objects for Deployment, edited by Monica Haller. Accessed August 4, 2015. http://www.veteransbookproject.com/the-books/.

Levy, Nadine. 2016. "Emotional Landscapes; Discomfort in the Field," Qualitative Research Journal 16 (1): 39–50.

Lincoln, Yvonna S., and Egon G. Guba. 1985. Naturalistic Inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Marchand, Trevor S. J. 2010. "Making Knowledge: Explorations of the Indissoluble Relation between Minds, Bodies, and Environment," The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute. 16: S1–S21.

McLaughlin, Colleen. 2003. "The Feeling of Finding Out: The Role of Emotions in Research," Educational Action Research 11 (1): 65–78. Accessed February 19, 2016. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09650790300200205#aHR0cDovL3d3dy50YW5kZm9ubGluZS5jb20vZG9pL3BkZi8xMC4xMDgwLzA5NjUwNzkwMzAwMjAwMjA1QEBAMA.

Pessoa, Luiz. 2008. "On the Relationship between Emotion and Cognition," Nature Reviews Neuroscience 9: 148–158.

Pink, Sarah. 2015. Doing Sensory Ethnography. 2nd ed. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Scheper-Hughes, Nancy, and Philippe Bourgois, eds. 2004. Violence in War and Peace: An Anthology. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Spencer, Dimitrina. 2010. "Emotions in the Field and Relational Anthropology," Accessed February 10, 2016. http://emotionsinanthropology.blogspot.com/2010/02/emotions-in-field-and-relational.html.

Stoller, Paul. 1997. Sensuous Scholarship. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.