Introduction

"Transportation is a big factor in our lives—especially people like me who ride the bus." Angel's voice echoed against the library walls. Sunlight streamed in through the windows illuminating rows of seats jammed with spectators at the culmination of our project, which began in January. It was May and graduation was around the corner. "I realize that you want to make things better for—not yourself—but for the people" (Public Testimony 2015b). The crowd applauded, shouting affirmations. Angel had accomplished more than learning about transportation or the arts; he'd made connections, formed opinions, and inspired others with his voice.

This essay is geared for arts educators and urban planners who are interested in socially engaged research with youth. Youth are a powerhouse for creative cities. However, the discourse on creativity and urban development rarely prioritizes the perspectives of young people of color in decision-making about urban spaces. Here I discuss the #Elara Moves project (EM)—a school-wide art integration and participatory research process about mobility in East Los Angeles. 1 I led EM with a team of teachers and students from the East Los Angeles Renaissance Academy (ELARA), facilitating, analyzing, and circulating youth knowledge about Safe Routes to School (SRTS) in the community.2 Studying the city through the arts allowed teenagers to amplify local knowledge, practice leadership, and envision alternative futures. Along the way, students cultivated agency as the heroes and heroines of their own stories, and learned how to intervene in urban systems that impact their daily lives.

Research Process

We began the project with participatory planning between myself and an interdisciplinary team of teachers: Hector Verduzco (new media), Michael Rocha (journalism), John Lee (Drawing), and Martin Buchman (Administrative Coordinator). We decided on the mobility focus, branded the project #ELARA Moves in order to archive and circulate knowledge on social media, and agreed to make a process book as a learning outcome. 3 Instruction took place from January through May 2015, with 82 ninth and twelfth graders.

Our key research question was "How do ELARA students get around?" Three core ideas about knowledge guided how I facilitated our research: 1. The arts are a powerful tool for creative inquiry about people and places. 2. Youth perspectives are important for understanding local conditions and making informed city-planning decisions. 3. Engaging teens in community-based inquiry inspires youth development. Students studied mobility through the four pillars of SRTS: safety, health, community, and choice.

The EM research process is akin to both participatory action research (PAR) and arts- based research (Fals Borda 2013; McIntyre 2000; Rolling 2013b; Barone and Eisner 2012). For Fals Borda, PAR prioritizes the expertise of everyday people, and grasps the connections between analytical and intuitive knowledge, or sentipensando (thinking-feeling). 4 McIntyre distinguishes PAR as a "collective commitment to investigate an issue or problem . . . a desire to engage in self and collective reflection; . . . action that leads to a useful solution which benefits the people involved" (2000, 15). Arts Based Research emphasizes "the forms of thinking and . . . representation that the arts provide" (Barone and Eisner 2012, xi). It provides "a flexible architecture for representing the world . . . grounded in the local site of inquiry" (Rolling 2013b, 49).

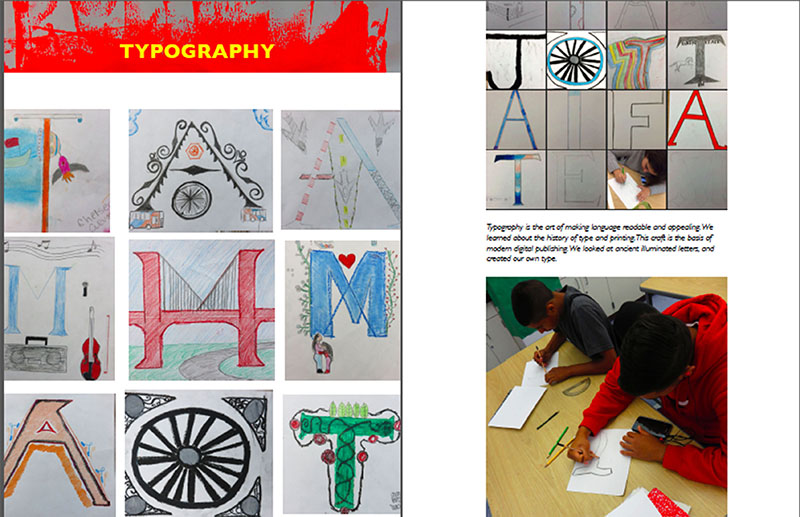

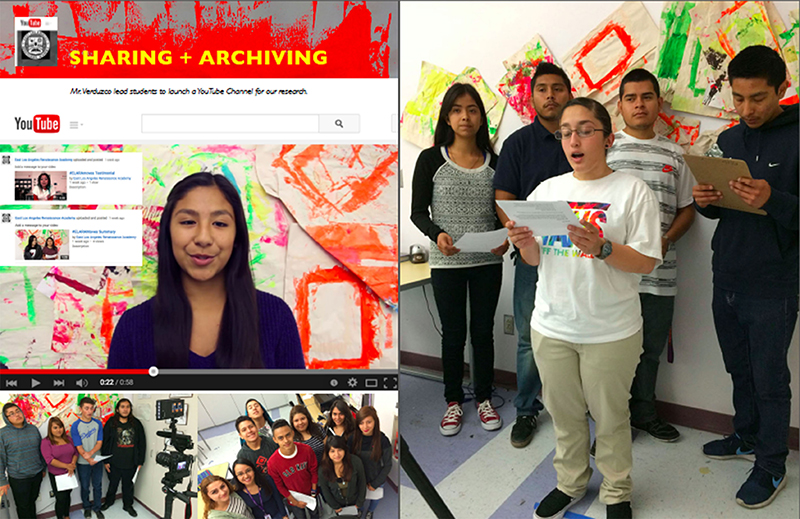

Arts integration combines more than one content area for learning. In EM, SRTS was our thematic trellis for teaching urban studies and the arts. Drawing on years of community-based arts-making, I wove information about SRTS into art-making activities in a range of classes. Journalism students wrote stories about notable trips to and from school, interviewed community members, and practiced cocreation through performance. Fine art students created photographs, drawings, paintings, and prints about modes of transportation, streets, and the built environment. They studied visual composition and design while illustrating ideas from the journalism students' writing, and inventing typefaces for the EM publication. The new media students mapped and analyzed their transportation routes with digital technology, and used image capture to report on danger getting to and from school, including poor illumination and collision-prone street corners. We analyzed student mobility survey data using Google Form analytics and critical discussions with students, and videoed student findings to share on YouTube.

Mobility conveys freedom of movement and is critical to the livability and sustainability of households, neighborhoods, cities, and regions. We sought mobility to get around the city in safe, affordable, and healthy ways that connect residents to affordable housing, public parks, quality schools, healthy food, work, and career options.5

I focused EM participatory research on SRTS because of its immediate relevance to youth. SRTS is a national mobility movement that aims to increase safety and access to active transportation (such as biking, walking, and skateboarding), encourage healthy lifestyles that improve public health, decrease carbon emissions to improve air quality, and foster neighborhood connections among students, families, school officials, and community leaders. SRTS expands mobility choices for young people, especially children who are marginalized in underserved areas. EM helped ELARA students inform themselves about mobility options, develop their own opinions about SRTS, and advocate for positive changes in the community.

EM circulated youth knowledge about SRTS through exhibitions, public speaking, blogging, social media, and a publication. I created a process blog (i.e., a simple website) to amplify student learning and as shared field notes to display in class. Students enjoyed being digital influencers and knowing they reached people locally and nationally. We used social media to amplify youth voices, disrupt geographic isolation, and help students envision online professional identities. They studied how to circulate information to broader audiences on Twitter and Instagram and witnessed how their ideas spread through "retweets" and "likes."

Conceptual Framework

Youth in the Creative City

Los Angeles is home to over ten million residents, 23% of whom are under the age of eighteen. As an urban planner, I care about how children shape and are marked by where they live and learn. As an artist, I know that residents of all ages and cultures can shape creative cities to be inclusive and sustainable. Cities are contested spaces shaped by histories of power and negotiation, inclusion and exclusion, destruction and renewal. Actively seeking to improve living and learning conditions for youth is critical to the cultural vitality of cities.

The role of creativity in enhancing urban life, creating a sense of place, and spurring economic activity has been widely studied (Markusen and Gadwa 2010; Florida 2005; Jackson 2014). However, less attention has been paid to roles for marginalized youth as future leaders of creative cities.6 James Haywood Rolling Jr. theorizes creativity as a powerful social force. He explains that "creativity originates as a social behavior, not an individual one. We think of his creativity or her creativity, but rarely do we think of our creativity" (Rolling 2013a, 6). Sarah Bainter Cunningham sees arts education of children as critical for urban spaces. She writes, "Arts educators may be the crucial lynchpin to providing residents with the ability to communicate their needs and articulate their own voice in shaping the city. Art and design literacies enable . . . children to make claims on what the city could be" (Bainter Cunningham 2013, 6).

As an artist and urbanist, I enjoy learning what kids think, what they have seen and overcome, and what they find funny, frightening, or inspiring about their communities. I facilitate mutual respect for student knowledge, and guide students through activities where they can take risks, be authentic, and practice leadership. I want my students to see themselves clearly—as respectable and evolving human beings. I facilitate creative learning by strengthening their art-making capacities while increasing their awareness of how cities work.

Who Knows the City?

The dictionary defines knowledge as "information, understanding, or skill that you get from experience or education; awareness of something" (Merriam-Webster Online 2015). It is critical to pay attention to the different kinds of knowledges—and knowledge systems—that are at play in classrooms and communities, and to affirm students and their families as knowledge bearers and knowledge creators. "Who knows?" is a simple, yet political question underlying this research. Sandra Harding (1987) writes that feminist methodologies question who can be a "knower." Harding recognizes that her theoretical claims exist within a historically patriarchal and racist educational system that has not valued the diversity of women's knowledges. Feminist methodologies ask questions that are relevant to women and girls who are themselves knowers, and use knowledge to help improve their lives.

Building on Harding's assertions, I argue that children are knowers, too. They know things that are valuable for making cities more livable. However, youth knowledge—especially that of marginalized children—is rarely consulted to inform sound decision-making about infrastructural or cultural resources. Harding also specifies that there is no one universal woman's knowledge. The same is true of children: there is no one universal youth voice. A Brazilian saying, Cada cabeça e um mundo (Every mind is its own world) captures the epistemological impulse of learning—that everyone has their own truth—and by extension, that the diversity of our truths inform the greater whole. Just like classrooms, cities are diverse spaces that can benefit from understanding the specific living conditions and aspirations of its diverse residents.

Paulo Freire provides a philosophical precedent for valuing children's knowledge. He critiques the banking system of education, where knowledge is seen as deposited by teachers who know things into students who don't (1970). Harding's post-colonial feminist epistemologies and Freire's Pedagogy of the Oppressed provide a useful theoretical frame for participatory, arts- and culture-driven research with youth about living conditions in their communities. Freire notes that the act of study evokes an attitude toward the world that he sees as a confrontation7 (1985). EM provided a healthy confrontation with arts education and urban planning discourse on at least two levels. First, youth research on SRTS confronted the adult-driven emphasis of city planning. Second, the interdisciplinary nature of our work (combining hard facts, intuitive imagery, and personal stories) disrupted disciplinary boundaries in arts education and urban planning.

At a basic level, art is about telling a story—whether literal or fictional. Toni Morrison saw power in the act of giving voice to silenced stories (1990). EM expanded the range of stories that are told, read, seen, and heard in order to amplify perspectives on mobility held by Latino teenagers in LA's Eastside. Designer John Maeda recommends that we rethink the value of storytelling in leadership development. He argues, "A leader doesn't start with storytelling, they start with story listening" (2014). Compassionate leadership, just like thoughtful design or art-making, provides an opportunity for people to listen better to each other. EM expanded opportunities for students to ask each other questions, to listen well, and to tell their stories to listeners who did not yet know them—including transportation decision-makers.

The Power of Voice

Students long to express themselves, be seen accurately, have their experiences valued, learn new things, and belong to a winning team. The pain of feeling voiceless, misunderstood, or presumed incompetent vexes the racist or sexist classroom. A social justice approach to arts education must do precisely the opposite—help students become the experts of their own representations, practice compassionate storytelling and story listening, and affirm the value of diverse identities, social conditions, and lived experiences.

It takes practice to learn to play an instrument, dance something choreographed, draw a portrait, or deliver a soliloquy. Students who have not had the chance to learn how to draw may grey their pages with erasures. Students who lack confidence in spelling or grammar may hover over a blank page with pencils frozen between their fingers—even if an assignment is given in free verse. Gloria Anzaldúa writes that healing can conjure back voices that have been socialized into silence. "En boca cerrada no entran moscas— 'Flies don't enter a closed mouth'"—she was told as a girl (1987, 76). Jacques Derrida suggested that the specter of invisibility must be confronted. He wrote, "One must see, at first sight, what does not let itself be seen. And this is invisibility itself" (1994, 3).

Children abound with creative ideas, impulses, and cultural assets, but, as Ken Robinson has noted, these tendencies are often stamped out of students instead of cultivated (2001). Students can be exposed to the arts and culture at home, in the neighborhood, or at school. A child's own autochthonous creative knowledge, grounded in their cultural identity and unique personality, is the root system for future artistic growth. We can fight invisibility by affirming youth voice and the rich connections between culture, identity, and art.

Seeing children as knowledge bearers instead of problems to solve is a first step towards creating an inclusive classroom culture ripe for creativity. Anzaldúa wrote about seeing and being seen as either a form of possession or a window for self-awareness:

Seeing and being seen. Subject and object . . . The eye pins down the object of its gaze, scrutinizes it, judges it. A glance can freeze us in place; it can "possess" us. It can erect a barrier against the world. But in a glance lies awareness, knowledge. (1987, 64)

Awareness of misrepresentation, or being seen by others in a negative light due to prejudice, was part of my cultural and political upbringing. My mother taught me about the "evil eye," and collected handmade amulets to protect her children from it. These wearable art works, stamped in metal, carved in red stone, or molded in blue glass, were designed to protect us from being injured by an outsider's negative gaze. It makes sense that I have worked as an educator to dispel potential for shaming, envy, or misrepresentation in the classroom by creating safe spaces where students can take risks, make mistakes, and demonstrate what they know and value. A child who sees herself as knowledgeable, can figure things out, and shape change will grow into an empowered adult.

Energy can also come from the process of invention itself. Noah Purifoy8 believed the process of making art was more powerful than any artworks created: "I am more concerned with the act of creating than I am with art itself. My primary concern is others getting into the act of doing something creative. Art is a tool to be used to discover the creative self" (Sirmans and Lipschutz 2015, 78). Importantly, Randy Martin suggests that making and performing art can activate participants to move from mere spectatorship to becoming political actors (Martin 1990, 1). Because of the lack of arts education in most urban schools, students can feel ill prepared to express the depth of their ideas through an unfamiliar medium. Helping students "get into the act" requires facilitating a culture of experimentation and positive risking-taking in the classroom that embraces failure as a part of the creative process.

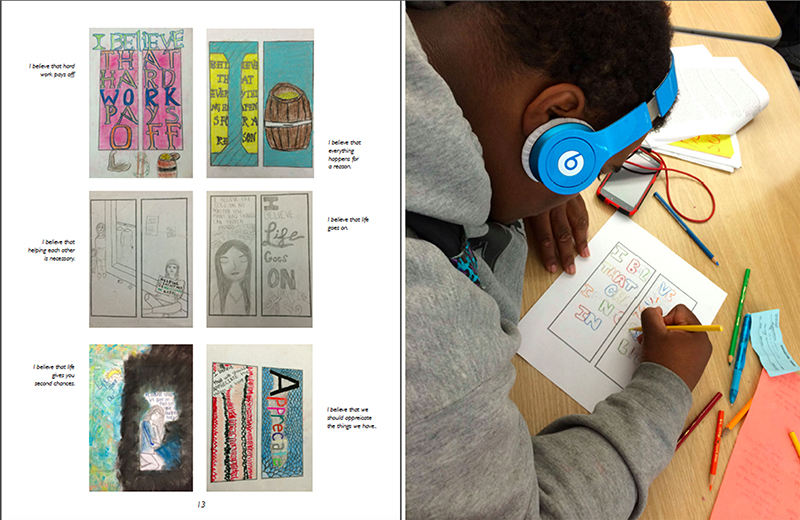

For example, EM ninth graders eagerly choose one of the twelfth graders' beliefs to illustrate, but visualization was more challenging. Some students began drawing immediately, while less confident students hesitated. One young man glared so intently at his page that I thought he would burn an image into the paper with his eyes. "Let yourself begin," I whispered. "You can always make it better later." He nodded with relief. "I always do that," he said. "I stop myself." He finally relaxed and got into the act.

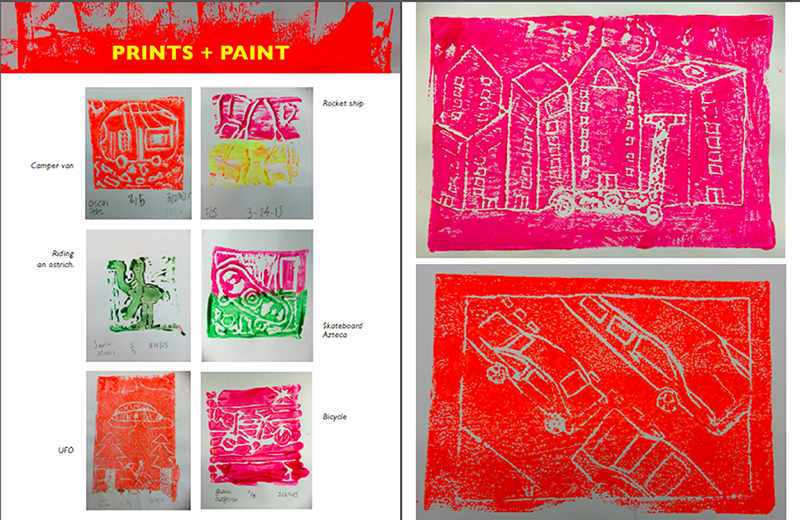

In EM, I varied the use of arts materials and performance techniques to emphasize process over product. Introducing printmaking welcomed new students to the joys of messy work. They liked moving around between the sketching, cutting, and printing phases of creation. This turned the classroom into a social laboratory for image making. I took a similar approach with writing students, using performance to build a culture of listening and speaking out. Facilitating a culture of experimentation in the classroom helps students face the empty page, the blank space, or silence with curiosity instead of trepidation about how to fill it. Artists face this challenge everyday. We practice honing our craft through technique, but when it is time to create we emphasize process first. Only after creating a body of work do we choose what we like best and what we don't during the editing, revising, and curation phases. We combined skill building through instruction with risk-taking in the creative process.

The Art of Knowing

The creative process is inherently driven by inquiry. In EM, our shared quest was to learn about the impact of mobility on students' lives through the creative process. Students expressed what they know and learned through visualization, physical and vocal performance, and digital tools. Local cultural, linguistic, and geographical assets affirmed students' knowledge and imaginations. Their art works were imbued with a sense of shared purpose, connection to regional histories, and invention of brighter futures.

The arts can be used to express, document, reframe, or critique human experiences and environments. Art-making is a platform to practice the powers of self-definition, cultural preservation, and innovation. Classrooms could focus on any topic through multiple media. The arts are languages and systems for knowing, as much as they are content itself. They activate holistic learning that intersects facts with feelings and weds subjective and analytical ways of knowing. Art-making offers outlets for students to express what they know, but, also, how they feel about what they know, what they want to know, and why they want to know it. A curriculum that incorporates feelings and perceptions strengthens student learning since cognition is a layered and complex process involving social and embodied language, thought, sensory perception, interpretation, and empathy (Kamenetz 2015). The arts provide a way to practice and develop proficiency in perceiving, communicating, and managing feelings—all valuable life skills for successful relationships and compassionate leadership.

The ability to communicate feelings and observations was central to EM. Safety is a pillar of SRTS and a topic about which ELARA students were experts, having witnessed violence on their way to or from school, or having lost family members to violence. The topic of safety could not have been adequately understood, or addressed, without students' stories and sentiments. Creative writing, drawing, and painting allowed the learning community to grasp the deeper ramifications of safety on students' lives. For example, violence was a central theme in students' observation stories. While one student told a humorous tale about a flock of chickens trying to cross the road, most of the observation stories were dominated by having witnessed violence. Reading the stories aloud in class generated empathy for each other and an awareness of the different risks facing males and females. Joel concluded, "Fear is a natural response and there's no shame in it, especially if the situation is very serious" (Shimshon-Santo 2015, 27). We brainstormed ways to increase safety through behavioral changes and by advocating for improved transportation infrastructure.

"Knowledge is power" is a common adage, but it is equally true that power restricts or expands knowledge. For example, while research has shown many benefits of arts education on student learning (Catterall, Dumais, and Hampden-Thompson 2012; Greenfader, Brouillette, and Farkas 2014; Shimshon-Santo 2010a, 2010b; Hanley and Noblit 2009), access to arts education reveals geographies of power, privilege, and exclusion across place, identity group, and socio-economic status (CREATE CA 2015). Investment in culturally relevant arts education during childhood expands the range of tools children can master to express themselves as creative thinkers, knowers, and makers. Preparing and encouraging students in creativity is an investment in the diversity of knowledge production and homegrown talent in cities.

How the Project Unfolded

Locale

ELARA is a public school with a formal urban planning and design focus on the Esteban Torres High School campus near Cesar Chavez Boulevard and Eastern Avenue on Los Angeles' Eastside. East Los Angeles is a creative mecca for Latino/a culture and ingenuity. The city's Latino roots reach down hundreds of years. East Los Angeles had become an intercultural crossroads molded in part by racial housing covenants limiting the ability of Latino, Asian American, African American, and Jewish residents to purchase homes in areas of their choosing. According to current census data, East Los

Angeles residents are now 92% Latino and 43% foreign born. Nearly one third of local residents are 18 or under. Neighborhood high school graduation rates are 46%, and just under 6% of local residents have completed an undergraduate degree (United States Census Bureau 2015).9 The community continues to organize in order to affirm local Latino identity and autonomy, support the well-being of its residents, and navigate the imposing pressures of gentrification (Masters 2012).

Approaching ELARA

On my way to ELARA, I pass the happiest ice cream shop in the world. Hand-painted on the doorway, in curly blue and green letters, are the words Aqui pasan las mujeres mas bonitas del mundo (The most beautiful women in the world pass through here). I veer under the crisscrossed freeway, over ramps, and turn right down a residential street lined with one-story, single-family homes. Parking in front of a house surrounded by a tall white metal gate, a neighbor's VATO LOCO Wi-Fi server finds my phone. I know that when the VATO LOCO Wi-Fi perceives my digital presence by popping up on my cell phone to request access, I have arrived.

There are no painted crosswalks or stop signs at this corner between the homes and the school. I wait for traffic to pass and run with my bag of art supplies and laptop bouncing up and down inside the sturdy orange bag woven from plastic thread that I purchased in Chiapas decades ago. With its simple, utilitarian construction it may outlive me. It is early morning. Students are scattered on the sidewalks and crossing the street, heading to A period.

A skateboarder wearing a green hoody circles the sidewalk next to the fire hydrant at the school entrance. We smile and exchange hellos. We have often talked about active transportation. I've taken his photograph and a group portrait with his skateboarder crew. My team of student researchers has done the same thing with hundreds of other local youth. We've been talking to skateboarders, pedestrians, bike riders, and car drivers about how they get around. Students have taken photos and made charcoal drawings of crosswalks, sidewalks, buses, and trains. The youth research team has been drawing, writing, making prints, mapping routes to school online using Google tools, and making videos for YouTube for months. We even got dressed up and took the bus downtown to speak with the Los Angeles Metropolitan Transportation Authority (METRO LA) about youth perspectives on SRTS. Invite an artist-nerd-in-residence to teach at your school and people get to know each other.

I open the heavy door to the main office and greet the front staff. I sign the lined visitors notebook and my hand reaches for a fluorescent yellow visitor sticker.

"You don't need one of those," says the middle-aged woman at the front desk. "I know you." She smiles.

"Gracias Madre," I say. I realize how much I've enjoyed seeing her on the way in and out of the school this year. We talk chisme. She briefs me on upcoming events. She asks me for updates about the students' progress.

I push past the swinging door, walk through the administrative building, and out the back by the nurse's office. The corridors are jammed with teenagers. The river of youth is speckled with radiant hair dyes, selective piercings, and backpacks personalized with permanent ink pens.

"Dr. A!"

"Good morning! See you in class?"

"Yes!"

I have come to love this place.

Learning by Doing

We have accomplished a great deal since the first day I met Michael Rocha's journalism class. I have developed a routine for introductions since my name is difficult to pronounce. I tell them my long, multiethnic, hyphenated name, and offer them a simple option.

"Hello, my name is Dr. A," I say. "I'm an artist and an adjunct professor at Claremont Graduate University. I believe that college begins before you apply to the university. I'm here because I want you to graduate high school and come visit me, come study in college."

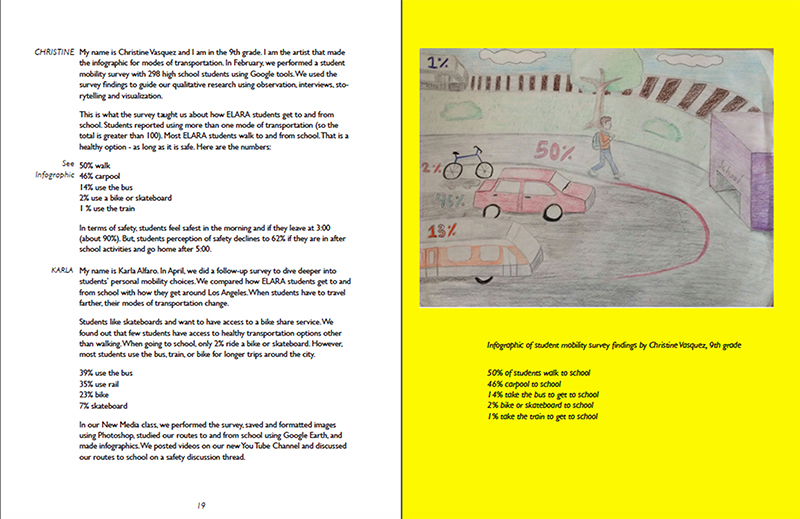

Throughout the EM project, we collected and analyzed quantitative and qualitative data on mobility. The team gained quantitative information from student mobility surveys in order to assess which modes of transportation students used to get to and from school, and their perceptions of safety. I presented the data to students to discuss in our arts classes. From the initial survey of over 200 students, we learned that 50% of ELARA students walked to school. Walking is a healthy way to get around if students feel safe. However, students' perceptions of safety declined significantly, from 90% at 8:00 a.m. to 62% after 3:00 p.m., when they returned home after school. This safety data was immediately significant for students, teachers, and administrators because the community regarded after-school activities as critical for college preparation, sports, and internships.

While biking or skateboarding are healthy choices, the survey revealed that only 2% of ELARA students biked or skateboarded to or from school. We discussed this finding in class, and students explained the reasons. Riding a bike to school made them targets for aggravated assault and theft, and bikes were often stolen from school during the day. Some teens didn't own a bike, or owned one that they were embarrassed to ride to school. Students determined that both safety and access to personal mobility devices influenced low bike ridership. Analysis revealed that many students preferred skateboarding to biking. Skateboards were associated with a positive youth lifestyle. Teens appreciated that they could leave their boards in the classroom, where they were less likely to be stolen than a bike.

The survey results provided a springboard to get students asking questions, thinking critically about SRTS, and making art. Student inquiry guided personal stories about epic walks to school, peer and parent interviews, photographs, drawings, paintings, prints, infographics, erasure poems10, and digital maps. In EM research, stories were written, spoken, and conveyed through visual art. The interdisciplinary approach brought valuable qualities to the research. For example, in our modes of transportation studies, writers told personal stories from their own lives. We learned about cars that stopped for chickens that were trying to cross the road, and kids being mistaken for criminals and harassed by the police. Students remembered the sounds of punches smacking against someone's bent over jaw during a fight, and the weight of a sweat-drenched T-shirt after running home in fear.

Fine art students depicted both conventional and imagined modes of transportation. They visualized bikes, skateboards, buses, trains, and pedestrians, and invented ostrich rides, Aztec skateboards, floating buses, and UFOs. Interactions between disciplines, and across age groups, imbued our learning with playfulness and breadth. The ninth graders reminded me that kids are as interested in exploring the universe as they are in simply getting to and from school. Young people want the freedom to move about freely—in the city or the galaxy.

One of the many EM arts activities I developed emphasized belief systems and overcoming adversity. It was inspired by the Edward R. Morrow This I Believe series, initiated during World War II. I asked students to write stories and poetry, and to draw based on their beliefs as a source of strength during challenging times like war or violence. Adolfo, a tall and athletic student, filled his pages with personal stories. He discussed being bullied in middle school and the impact it had on his health. His belief: "I believe that people can change":

With the shock of my father deserting us, my mother could no longer keep track of my nutrition and I didn't care about what I was eating. As I became heavier people became meaner. At some point, I even began bullying myself. (Shimshon-Santo 2015, 11)

Adolfo used creative writing to reframe his transformation from a victim to a confident high school student who was graduation-bound. By the project's culmination, he described this activity as his favorite, because he got to know his peers on a deeper level and to respect them more.

Each student's story of overcoming an obstacle generated a shared pride in the group's resilience. One day, we studied a podcast by Elvia Bautista (2006) who had lost her brother to gang violence. A student called me over to talk. It was the one-year anniversary of her father's death from what she described as bad decisions. She chose to frame her story as a way to honor her deceased father. "I believe my dad is still with me even though he isn't really here anymore," she wrote (Shimshon-Santo 2015, 12). Helena, who shared a desk with her, used the activity to critique an abusive relationship. She wrote, "I believe that when a couple breaks up they should respect each other and let go" (Shimshon-Santo 2015, 11). One student encouraged everyone to be grateful for their parents since he had almost lost his father during a raid by the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). He explained that he would not be in school today if his father had been taken from his family. Instead, he would be working full time to support his household. Another student emphasized second chances after she overcame childhood meningitis.

The twelfth grade journalism students swapped their work with the ninth grade visual arts students who chose favorite beliefs to illustrate. Sharing writing and imagery connected students across ages and disciplines. Students forged leadership beliefs and authority grounded in shared experiences, values, and aspirations.

As the project culminated, students analyzed their core findings, and rehearsed their presentation for the Metro LA headquarters. Rehearsal was critical for leadership development. As a retired choreographer, dance had taught me the power of practice. We rehearsed until the movements were embedded in our sense memory and felt natural. Practice freed us to fill the form with our own identities and unique performance qualities. Students diligently rehearsed their message, pitch, and posture.

I collaborated with Tham Nyugen and Lisette Covarrubias in Metro LA's Active Transportation office to facilitate an intergenerational exchange between students and Metro professionals. Adults were selected for cultural competencies and leadership qualities that celebrated Latinidad, immigrant experiences, identities as first-generation college-goers, and Eastside residents. The exchange began with a panel of adult transportation professionals and concluded with the EM youth research presentation. The transportation experts inspired the students to aspire to college and a professional career that could shape the city. The youth impressed the adults with their artworks, infographics, stories, mobility analysis, preparation, and confidence.

Lisette Covarrubias asked the EM team, "What is preventing students from moving through their own environment?" Students talked about safety and their experiences of active transportation. They requested increased service during peak hours (when students are on their way to or from school), since buses filled to capacity were leaving students on the curb. They advocated for better street lighting, so when they walked home at night they would feel safer. They wanted painted crosswalks to deter automobile collisions with pedestrians. They asked how to reduce speeding and hit-and-runs near schools, and requested shaded bus stops. They explained that many students don't have access to bikes or skateboards, and requested that Metro locate a bike-share service on the Eastside. 11 They advocated for free or affordable transit passes for low-income students.

The hearty debate demonstrated that EM prepared youth as leaders able to speak authoritatively about their vision for SRTS in the neighborhood. Students trusted their ideas because they were grounded in rigorous group research informed by multiple methods. A blogger from Metro, who attended the event and was enthusiastic about the students, wrote:

The city being built now is the city that they're probably going to live in for the next few decades—so it makes sense they'd want to know about the process of how it's being changed and have some say in what's going on. Hopefully they were able to take away some useful information from Metro—and vice versa! And who knows? In a few years, maybe these high schoolers will be the ones calling the shots in shaping Los Angeles. (Chen 2015)

We then prepared to share stories though public testimony (i.e., an Open Mic) and an eBook Launch at the school library. While practicing for the Open Mic, Edwin faced his peers with a serious look and said, "My fellow Americans." Everyone laughed, including him. I saw this as a form of role-play as he defined his own leadership style.

Nadine expressed her pride in participation and "voicing the voice":

In this whole experience, I got to know how we can involve each other in our community. . . . Everyone stood up and expressed themselves and the spotlight was on them. It made me open up and realize that we are individual people. I am proud to see that teenagers can voice the voice and be heard." (Public Testimony 2015b)

Yakeline was shy to take her turn at the microphone. She summoned her courage and said, "If we want change in our community, we have to get out there and let them know what we would like" (Public Testimony 2015a). The once-timid student received rousing applause from her peers.

Esteban described what he learned as something new and memorable:

"The process . . . was pretty hard at times. But, in the end, it was all worth it. To go up on stage in front of the podium and talk with the people from Metro and tell them our experience of this (SRTS). It was . . . once in a lifetime and really fun." (Public Testimony 2015b)

On the last day, students and teachers gathered in the school library. John Lee and his students displayed EM book spreads they had mounted on poster board. With a few clicks, students downloaded the publication and archived it in the school library alongside other published writers and artists. Students scrolled through the publication online, smiling and pointing at their contributions and favorites.

Students discussed what they did and learned in an Open Mic session. The teachers spoke about student achievements with pride. The twelfth graders described their experiences with words like work and belonging. "I am a member of #ElaraMoves," began many of the student testimonies. The ninth graders had chosen seats in the back rows. After seeing the seniors brave the microphone, they came forward to speak and be heard. Then there were handshakes, hugs, photos snapping, and trays of sandwiches to be eaten. Students left the library that day as published authors, exhibited artists, and emerging urban experts on mobility in the city.

Conclusion

The EM project synthesized arts and design education with urban studies, while investing in students as emerging leaders. Students cultivated leadership through inquiry that exercised their intellectual and creative capacities. They created original art, and developed skills in editing, curating, rehearsing, performing, and publishing. Students shared their knowledge across distinct settings—from downtown skyscrapers to their own neighborhood. The research process revealed that youth have valuable urban expertise, and that their visions, opinions, and imaginations can help inform more inclusive and livable cities.

Studying mobility provided the groundwork for intergenerational connections between the high school students, higher education, and city agencies in the area. A focus on the city inspired students and teachers alike. Karla, an enthusiastic ninth grader, became an urban advocate in her drawing class. She wrote:

It's great talking about transportation in the city, because in our city people mostly use cars. This is the reason why we have so much pollution and smog. I think other schools should also start focusing on the city more because . . . you could actually realize that there is a lot wrong with it and that we can try to fix it together. (Shimshon-Santo 2015, 16)

English teacher Michael Rocha claimed that the project helped his students see themselves as change makers:

This project pushed students to . . . to investigate current issues in their community and become agents of change. As our students interviewed their peers and their families they gave voice to the challenging nature of life on the Eastside; they honored those voices by proposing changes to the community. (Shimshon-Santo 2015, 5)

"Being a part of ELARA Moves was a natural fit," wrote New Media teacher Hector Verduzco. "Students used Google Earth to map their routes and analyze safety concerns they have on a daily basis" (Shimshon-Santo 2015, 5). Design teacher John Lee was pleased with the college preparatory focus that helped his students prepare for future careers in the arts and design.

This study suggests that arts education can generate qualitative and spatial knowledge for understanding cities and activating communities. The project's scale influenced a school culture by sparking creative learning across multiple disciplines and grade levels in both arts and non-arts based classrooms. EM generated, studied, and influenced local knowledge about a key urban system—transportation—by engaging youth and amplifying their voices with decision makers.

Notes

1 The author is grateful to Faith Davis and Exploring the Arts for support of the EM project.

2 More information on Safe Routes to School is available through the National Center for Safe Routes to School at http://www.saferoutesinfo.org/.

3 The project process book is available open source at https://elaramobility.files.wordpress.com/2015/05/elaramoves_ebook1.pdf.

4 Orlando Fals Borda said, "We act with our hearts but we also apply the brain. When we combine these two things, we are sentipensantes [feeling-thinking people]" (Fals Borda 2015). Sentipensante influenced Eduardo Galeano's literary philosophy and became critical to community arts works in Latin America. See ¡Viva! Community Arts and Popular Education in the Americas (Barndt 2011).

5 While Los Angeles is known for car culture, freeways, congestion, and poor air quality, the region is taking strides to transform its transit infrastructure (Move LA 2015).

6 Richard Florida describes the creative economy as a "tectonic force . . . upending our jobs, lives, and communities" (2005, vii). Maria Rosario Jackson (2014) notes that communities of color strengthen cities and regions by providing a sense of identity, place, and social cohesion.

7 Freire wrote, "A book reflects its authors confrontation with the world" (1985, 3).

8 Purifoy was a master sculptor and installation artist. He also led the Watts Towers Art Center and served on the California Arts Council Board shaping arts policy.

9 According to census data, 31.5% of East Los Angeles residents are 18 or under; 91.7% are Latino— double the occurrence for the city at large; 87.6% speak a language other than English at home; and 42.9% are foreign born.

10 Erasure poems are created by erasing words from an existing piece of prose or poetry to create new meaning. This method is a form of found poetry.

11 Bike-share systems provide bike access to rent or borrow a bicycle from a bike dispensary and return it to another location in a service area.

Work Cited

Anzaldúa, Gloria. 1987. Borderlands: La Frontera: The New Mestiza. San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books.

Bainter Cunningham, Sarah. 2013. "The Mute Child in the Creative City," Paper presented at Face to Face 2013, NYC Arts Education Roundtable, New York.

Barndt, Deborah, ed. 2011. ¡Viva! Community Arts and Popular Education in the Americas. New York: SUNY Press.

Barone, Tom, and Eliot W. Eisner. 2012. Arts Based Research. Los Angeles: Sage Publications.

Bautista, Elvia. 2006. "Remembering All the Boys," Accessed on March 10, 2015. http://thisibelieve.org/essay/21255/.

Catterall, James S., Susan Dumais, and Gillian Hampden-Thompson. 2012. The Arts and Achievement in At-Risk Youth: Findings from Four Longitudinal Studies. Washington, DC: National Endowment for the Arts.

Chen, Anna. 2015. "The Future of Urban Planning: Students from East Los Angeles Renaissance Academy Visit Metro," Accessed on September 1, 2015. http://thesource.metro.net/2015/04/29/the-future-of-urban-planning-students-from-east-los-angeles-renaissance-academy-visit-metro/.

CREATE CA. 2015. Blueprint for Creative Schools. http://www.cde.ca.gov/eo/in/documents/bfcsreport.pdf.

Derrida, Jacques. 1994. "What Is Ideology?" In Specters of Marx, the State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning, and the New International. translated by Peggy Kamuf, New York: Routledge.

Fals Borda, Orlando. 2013. "Action Research in the Convergence of Disciplines," Translated by Luis Marcos Sanders. International Journal of Action Research 9 (2): 155–167.

———. Orlando Fals Borda—Sentipensante, Interview. Accessed on November 5, 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LbJWqetRuMo.

Florida, Richard. 2005. Cities and the Creative Class. New York: Routledge.

Freire, Paulo. 1970. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Bloomsbury.

———. 1985. The Politics of Education: Culture, Power, and Liberation. Westport, CT: Bergin & Garvey.

Greenfader, Christa Mulker, Liane Brouillette, and George Farkas. 2015. "Effect of a Performing Arts Program on the Oral Language Skills of Young English Learners," Reading Research Quarterly 50 (2): 185–203. doi:10.1002/rrq.90.

Hanley, Mary Stone, and George W. Noblit. 2009. Cultural Responsiveness, Racial Identity, and Academic Success: A Review of Literature. Pittsburg: The Heinz Endowments.

Harding, Sandra, ed. 1987. Feminism and Methodologies: Social Science Issues. Bloomington: Indiana.

Jackson, Maria Rosario. 2014. "What Are the Makings of a Healthy Community?" In The Role of Artists and the Arts in Creative Placemaking, Washington, DC: Goethe Institute.

Kamenetz, Anya. 2015. "Nonacademic Skills Are Key to Success. But What Should We Call Them?" Accessed on May 28 , 2015. http://www.npr.org/sections/ed/2015/05/28/404684712/non-academic-skills-are-key-to-success-but-what-should-we-call-them .

Markusen, Ann, and Anne Gadwa. 2010. Creative Placemaking. Washington, DC: National Endowment for the Arts.

Martin, Randy. 1990. Performance as Political Act: The Embodied Self. New York: Bergin & Garvey Publishers.

Maeda, John. 2014. "From Storytelling to Storylistening: John Maeda," Future of Storytelling. Accessed on 1 June 1, 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U8-Q70gV2Yk

Masters, Nathan. 2012. "L.A.'s First Freeways," Accessed on July 14, 2015. http://www.kcet.org/updaily/socal_focus/history/la-as-subject/las-first-freeways.html.

McIntyre, Alice. 2000. Inner City Kids: Adolescents Confront Life and Violence in an Urban Community. New York: New York University Press.

Merriam-Webster Online. 2015. Accessed on October 6, 2016. http://www.merriam-webster.com/.

Morrison, Toni. 1990. Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination. New York: Vintage Books.

Move LA. 2015. "Transit Rich Places," Accessed on August 22, 2015. http://www.movela.org/transit_rich_places.

National Center for Safe Routes to School. 2015. "Safe Routes," Accessed on January 5, 2015. http://www.saferoutesinfo.org.

Public Testimony. 2015a. Class rehearsal for Open Mic, Esteban Torres High School, Los Angeles, CA, May 22, 2015.

———. 2015b. Open Mic, Esteban Torres High School, Los Angeles, CA, May 27, 2015.

Robinson. Ken. 2001. Out of Our Minds: Learning to Be Creative. Chichester, UK: Capstone.

Rolling, James Haywood Jr. 2013a. Swarm Intelligence: What Nature Teaches Us About Shaping Creative Intelligence. New York: St. Martin's Press.

———. 2013b. Arts-Based Research, New York: Peter Lang Publishing.

Shimshon-Santo, Amy, ed. 2010a. Arts = Education: Connecting Learning Communities in Los Angeles. Irvine, CA: Center for Learning Through the Arts and Technology, UC Irvine.

———. 2010b. "Arts Impact: Lessons from ArtsBridge," Journal for Learning Through the Arts (6) 1.

———. 2015. #Elara Moves. Los Angeles: Creo Worldwide.

Sirmans, Franklin, and Yael Lipschutz. 2015. Noah Purifoy: Junk Dada. New York: Prestel, in conjunction with the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

United States Census Bureau. 2015. "Quick Facts," Accessed on July 17, 2015. http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/06/06037.html.