Summary and Goal

An adult day center with programming for people with dementia and adults with developmental disabilities. A nursing home (serving nearly 75% people with dementia). A robust group of elders in independent apartments. An Intro to Women's Studies class and a class of acting students, both at an urban, public university. In a yearlong, collaborative project, this diverse group came together to explore how the dreams and opportunities for women have changed across the generations. We share it here in order to relay lessons we learned about creating and implementing arts-based practices that speak across curricular disciplines, cognitive and physical abilities, cultural backgrounds, generations, and academic and community settings.

The Creative Trust, an alliance formed to foster life-long learning through the arts, was born in 2012 as a way to maintain and deepen partnerships among aging services providers and arts educators. Trust members include traditional retirement communities, as well as services/programs to reach elders who are living at home (home-delivered meals, volunteer visit/call programs, etc.). Elders, arts students, and faculty who teach engaged arts courses are also part of the team attending our open, quarterly meetings. See http://creativetrustmke.com/ for more.

The idea for the project came from a UW-M Theatre Department meeting when, after selecting the musical Little Women for the season, a colleague asked Anne Basting what kind of community-engaged project she could do surrounding it. "You do Little Women—I'll do Slightly Bigger Women, " Basting said—and so it was slotted into the season in the spring "alternative/black box" space.

The novel Little Women tells the story of the four March sisters growing up in Concord, Massachusetts. Their father is off fighting in the Civil War, and their mother (Marmee) struggles to make ends meet. The sisters have distinct personalities. The oldest, Meg, is quite serious and rule abiding. Josephine, who goes by Jo, dreams of being a writer and creates melodramas for her sisters to perform. She pushes against all codes of society that restrict the roles of women to the home front. Beth is quiet and thoughtful, and acts as a foil to Jo. She catches scarlet fever and dies in the course of the novel. Amy, the youngest, is confident and brash and is determined to return the family to its former economic status by marrying a wealthy man. Laurie, the lonely neighbor boy being raised by his wealthy grandfather, is warmly enfolded into the March sisters' games and dreams. Laurie falls in love with Jo, but after she rejects him, he eventually marries Amy.

The gold standard in engaged theater is "of, for, and with" the community one works with. In this case, it would mean that the elders and students would shape the content, perform, and attend. But production schedules, curricular needs of the Theatre Department, and student schedules do not fit the schedules of elders, particularly given our aim to engage multiple sites and people with cognitive and physical disabilities. How could we create a flexible project with opportunities for meaningful expression, engagement, and representation in the public presentation of the work?

Process and Curriculum

We drew on the themes and story of Louisa May Alcott's 1868 classic, Little Women, to guide us, including letter writing (creating a "mailbox in the hedge"), exploring gender roles as the March sisters do in the melodramas they enact in the attic, and exploring "castles in the air"—students' dreams of who they hope to become. In the September Creative Trust meeting, we arranged for care communities to host screenings and post-show discussions of the three film versions of Little Women (1933, 1949, and 1994). While students were invited and care communities promised snacks, few students actually attended. The discussions were vibrant. Basting asked one group of elders to raise their hands if they had read the book and nearly all of the roughly 25 people gathered did. "I read it 19 times," said one woman. "It was a revelation."

At that same September Creative Trust meeting, Basting arranged to hold workshops in the care communities, assisted by students enrolled in her Performing Community class and Theatre BA students working on their capstones assignments in community arts. We held three types of workshops: 1. "What is Ladylike?" which explored gendered movement; 2. "Castles in the Air," a discussion of who they dreamed of becoming, and what social forces shaped those dreams; and 3. "Changes," a discussion of historical changes that shifted what dreams are possible, and what changes still need to take place. We audio-recorded and transcribed the workshops, making sure the sound quality of participants' comments was high enough to use in the performances, if desired.

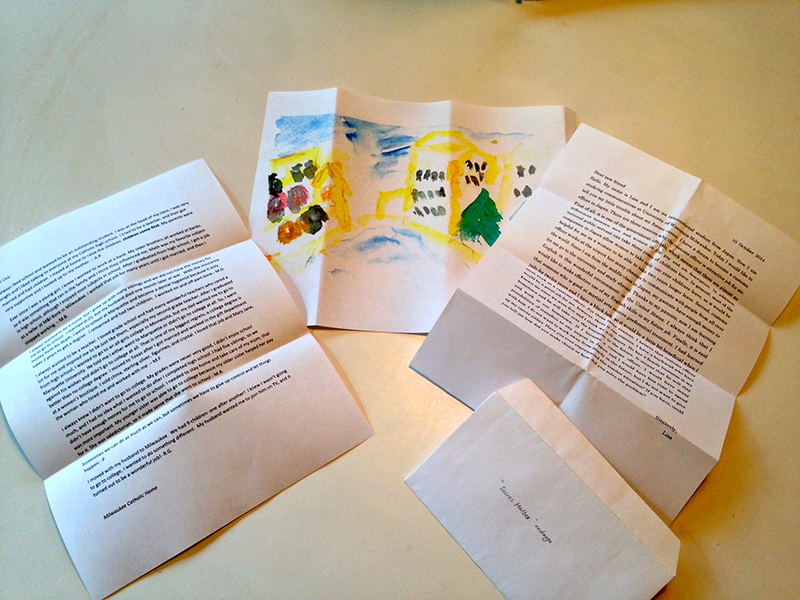

Women's Studies Instructor Casey O'Brien and Basting collaborated on an assignment for O'Brien's Introduction to Women's Studies class, in which students would write a letter (preferably by hand) describing their own "castle in the air" and what social pressures shaped that dream, either positively or negatively. O'Brien would copy the letters (with student consent) and Basting would deliver them to mailboxes created by the care communities. The staff at the care communities would coordinate the delivery of the letters the elders wrote in reply, back to Basting, who in turn passed them on to O'Brien and her students. We arranged two exchanges.

To accompany this project, O'Brien assigned Little Women and discussed it alongside other course materials, examining the roles gender plays in organizing society in Alcott's world. To prepare students to correspond with the elders, O'Brien assigned students to "write a letter about a seminal moment in your life when you knew what you wanted to 'become when you grew up.'" Students were further asked to "reflect on your locations at intersections of identity and privilege that affect what is possible for your career." (See The 'Secret Mailbox' Letter Writing Assignment for the complete assignment prompt. ) These reflections became the locus for our semester-long examination of the social construction of gender. Although the students' personal letters were not shared with their classmates, the letters served as a primary text for each student, as through them, students were asked to analyze ways in which gender identity reveals and conceals career possibilities.

The letter exchange was a profound experience for both the students and the care communities. Students wrote long letters, some of them hand decorated and including photos or gifts, detailing their life dreams and family stories. While students did not know to whom they were writing the first round of letters, several openly shared stories of emotional abuse or struggles with sexual identity. Some students shared stories of the generational and cultural challenges of being the first child to attend college. The majority struggled with choices of careers—identifying dreams, but with no shortage of uncertainty that they could achieve them. At first, staff reported that the elders were cautious in responding to the long and very personal letters—perhaps evidence of generational differences in comfort with "over sharing." But in response, perhaps following the young letter writers' lead, they told stories of their own dreams, how they evolved, and their support of, and astonishment at, the boldness of the young women's dreams. Some elders shared stories of loss of spouses and living amidst grief. They told stories of their first jobs, of their children, and of the limited choices they faced as young women. In some instances, staff read the letters aloud to participants with dementia, and as a group they responded with stories, thoughts, and even paintings.

In class, students read and discussed the letters they received from the elders. They were touched by the elders' personal stories and paintings. One student could not read her letter in class because the voice of her pen pal reminded her of her recently deceased grandmother. Others read letters that eloquently detailed their lives, marriages, children, and grandchildren. Many wished the students well on their career paths, lamenting that they did not have the same opportunities as young women.

Basting analyzed the letters thematically, and pulled highlights of the exchanges to share in the eventual playscript. In O'Brien's class, students talked about being moved by the encouragement of the older women, especially those students whose choices were not popular in their own families. Students also observed the dramatic increase in the choices available now, including expression of gender and sexuality, and gender roles in both work and personal life. Reading the life experiences recorded in the letters from the elders put the course content in context, and made the concepts of our joint courses more real and meaningful.

As the fall went on, Basting selected students to work as cowriter, assistant director, sound and light designer, and props designer/master. Cowriter student Tina Binns and Basting outlined a structure that would introduce the characters and themes from Little Women, feature the voices of the elders in the form of both letters and audio, and use dialogue to directly engage audiences in envisioning changes that still need to take place in order for people to reach their full potential.

Performance and Engagement

While some audience members might have seen the musical (which ran the month before Slightly Bigger Women in the same theater space), we were careful not to assume any previous knowledge of the story. The opening scenes establish the time and place, as well as the sisters' relationships as they playfully prepare for Christmas, wistfully dreaming of gifts they can't afford. The stage directions describe the actions as "almost Hallmark sickly sweet," suggesting that we are already commenting on the time period and consciously creating a layer between actor and role. This space between character and role continues to widen during the performance, as the characters begin to question their own plot lines and social codes, and as they learn that their world is actually embedded in 2015.

In the world of the play, Jo March has written a book about the lives of her sisters and family. The first of three sections portrays several scenes from the novel, including preparations for Christmas; the portrayal of a melodrama (of Jo's creation) featuring "Lady Zara;" a picnic at which the girls share their dreams of who they will become; and the frantic search for Meg's glove. Jo calls for her book (an enormous and heavy black book, dutifully brought in by the warm and cheery Marmee) on several occasions, in order to correct the action. Pretty Meg will marry Laurie's tutor, the humble John Brook. Beth will die of scarlet fever. Amy will marry Laurie. Jo will become an acclaimed writer and marry the German tutor. Laurie will go into his grandfather's business and look out for the fortunes of his beloved March family. "The book" is a metaphor for the social constraints the characters feel; eventually the sisters rebel against playing the same roles and plot lines.

Beth grows particularly frustrated and demands they redo the scene, and this time, she gets to live. Frustration reaches a breaking point as the sisters bicker over a lost glove that Meg needs in order to attend a party. Jo opens a hope chest to look for it—only to hear the voice of an elder say, "Gloves are stupid."

In the second section of the play, the March sisters' four hope chests are transformed into portals to the future, containing voice recordings from the workshops and letters from the exchanges between students and elders. The sisters, Marmee, and Laurie leave their bickering aside and are drawn together to marvel at the historical changes revealed by their hope chests.

Energy builds as the characters read letters about young women wanting to become detectives, dancers, and doctors. There seems no limit to the possibilities. They eagerly restage the scene in which they picnic and share their "castles in the air," only now they dream bigger, guided by a mysterious new knowledge of the future. Amy still longs to be an artist, but when asked what kind, she says, "I see myself smeared in chocolate in a black box theater." Beth is overwhelmed by the choices, but settles on becoming an "MD/PhD communicable disease specialist." The characters jubilantly dance to "Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy." Yet there are hints that there are still changes to be made, and in the third and final section, the house lights come up and the characters are shocked to see the audience, with Beth exclaiming, "They are all wearing pants!"

Bravely, with clipboards magically pulled from the hope chests, the actors venture forth to ask spectators, "What changes still need to take place?" The actors ask simple questions at first, to warm up the audience and to build their own confidence in talking to people from the future. "Hello," braves Jo. In each show, an audience member eventually responds in kind, sending the performers into an excited titter. "Is this 2014?" followed Jo. (No, 2015.) Slowly, the questions became more complex as the cluster of actors (clumped together out of fear of what might come next) shuffled comically from one section of the audience to another. "Have you been . . . watching us . . . this whole time?" (Yes.) After this initial audience engagement, Jo orders her team to split up and gather responses onto the clipboard. They fan out in pairs and ask more pointed questions. They gather the responses, and shout them to each other with excitement as they come in. "Do people still die of scarlet fever?" asks a sheepish Beth. (No, says the audience.) "Who wins the Civil War?" asks Marmee, and the answer is greeted with much celebration.

Finally, the characters ask questions about what changes the audience thinks still need to take place. Responses fall into similar categories in the rehearsals (with sample audiences) and in the performances, including: a woman president, more funding for education, and more equal roles for men and women in work and home life. Replaying the melodrama from the first scene one last time, the performers add these elements to the Lady Zara story. Each night is a unique performance, but it usually includes Lady Zara as president and Rodrigo as her supportive househusband. Inspired by these visions of the future, Jo vows to write a new book, and Marmee suggests it's time for them to go out into 2015. "What will you do?" she asks. One by one, the performers drop character and articulate their own visions for the future and their place in it. The play ends with a rousing version of Queen Latifah's "Ladies First," overlaid with the voices of the elders describing their visions of the future captured in workshops earlier in the year.

The structure of the play was challenging for beginning acting students. It combined Brechtian acting techniques (such as using stylized gestures); improvisation in movement, content, and character development; elements of docudrama (the reading of segments of the letters aloud); and ultimately, the ability to drop character and authentically play one's self. Dress rehearsals took place in the care communities, enabling the participating elders to be active audience members and see and respond to how the workshops were evolving into a performance. Student designers created the show to travel easily: simply four plastic tubs to act as "hope chests;" a computer and speakers to play sound; and a large, empty poster frame. The community sites themselves provided elements like tables and chairs.

Audiences at the Jewish Home and Care Center and at EastCastle Place were raucous. Hearing their own voices emerge from the hope chests, listening to their letters read aloud, and seeing how their input shaped the script itself had a powerful impact on the elders, as they and staff both reported to us.

We also arranged two matinee performances in the Theatre Department's black box space, and promoted the Sunday matinee as the time for the letter writers to meet face-to-face. The elders who attended had a rewarding, intergenerational experience with younger audience members. Because the Introduction to Women's Studies class had met the previous semester, O'Brien had little leverage to compel them to attend. Of the students who did attend, two had their letters featured in the performance. One of those students, whose letter detailed being distanced from her Polish-immigrant father because of her sexual identity, remarked to O'Brien that hearing her letter read out loud was "an emotional experience." She went on to explain that being accepted by these contemporary actors, portraying nineteenth-century characters, made her experience "very real." It seemed transformative for this young student to gain acceptance from her community, where she did not have it from her father.

Finally, assistant director Devlin Grimm designed an interactive lobby display to engage audience members and cast/crew after the performance. Posters provided historical context for Little Women, including information on the popular transcendentalism of the time; the letter exchange; and questions encouraging audience members to write their own thoughts about needed change and clip them on strings with clothespins. The display grew with each performance, as the actors added cards with audience feedback gathered after each show.

Watch a brief video of excerpts of the production here https://vimeo.com/126529779.

Click here to read the full and final script of the performance of Slightly Bigger Women.

Discoveries

The framework of a large, collaborative, arts-based project gave students, elders, and staff permission to express themselves in ways they might not otherwise have done. The project provided a grander purpose and a venue for public sharing of work that generated social capital—meaning and value—for the participants. The variety of activities created multiple ways for people to participate, depending on interest and ability. Not everyone involved in the project was interested in, or able to, perform in the play. We successfully found alternative ways to engage elders in the project, including the letter exchange, film screenings, workshops, and audience participation. By staging dress rehearsals in the care communities themselves, we were able to bring the performance to those who might not otherwise be able to attend, and to give them the first look and the ability to provide feedback for shaping the final product.

The use of Little Women as a theme/prompt effectively fostered intergenerational collaboration and exploration of gender. Among the generation currently in their 80s and 90s, there are strong and positive memories of the characters from Alcott's book. "That Jo March could be a writer was a revelation," said one woman during a conversation about the limited roles women could choose from (usually nurse, teacher, wife/mother, or secretary). The March family's neighbor Laurie (Theodore Lawrence), also plays with gender roles—he longs to be a musician, but his grandfather insists he go into the family business. The March sisters play male roles in the original melodramas they perform in their attic, and are horrified when Jo invites Laurie to perform with them, as social codes of the day were critical about women on the stage.

Teaching Little Women in a contemporary Women's Studies class runs the risk of appearing passé, as students assume that the gender roles would not speak to their twenty-first-century lives. However, the book proved surprisingly rich for the students to engage in discussions of gender norms. Reflecting on reading Little Women, one student remarked on what seemed to her to be its anachronistic, underlying gender norms:

Because Little Women was written so long ago, it is easy to see differences in gender norms. . . . Many of the norms of this period seem to be very antiquated by today's standards—a specific example being when Jo voices her disappointment at not being able to be a soldier or attend college. The girls' jobs, specifically Meg's job as a nanny, show the limited employment options during this time. However, Amy and Meg's concerns about their appearance and desire for beauty illustrate that some gender norms persist through time. The fact that some of these gender norms seem antiquated shows that they are socially and culturally constructed; our culture has changed with time, which has resulted in changes to our norms. The unchanging aspects of gender norms (the focus on female beauty) illustrate the fact that patriarchal societies have been using many of the same strategies to oppress women historically.

Illuminating gender mores as a socially and culturally constructed process, students could better see how gender and sexual norms and expectations are defined by the historical location in which they exist. With Alcott's vivid descriptions of gender standards, pressures, and policing, students could better understand that gender is not fixed or universal; rather, it is fluid and always changing. Furthermore, by pairing an examination of Little Women with our "Secret Mailbox Letter Exchange," students received personal details directly from women born in the early–mid-twentieth century, exposing them to the evolution of American gender norms and expectations spanning over a century.

Reading a fictional account of the constraints placed on women's dreams in the nineteenth century and nonfiction accounts from elders in the twentieth century provided a foundation for understanding concepts such as "biological determinism" and "the glass ceiling." Many students were stunned to learn about the lack of career options and the obstacles in place for the elders in the letter exchange. Students could read about these lives and realize the chasms dividing Alcott's generation, the elders' generation, and their own. Between each of these generations were women galvanizing the first and second waves of the women's movement.

We cast a transgender actor, Graham Billings, as Laurie, which added another layer to gender performances in the production. It is possible that audiences were not initially aware of the casting choice. Issues of transgender representation never emerged in the audience dialogue section of the play, or in the handwritten responses that filled the lobby display. But during rehearsals and in the production process, Graham's presence raised the level of awareness among the cast and crew of gender construction in dialogue/text, costuming, vocal choices, and physical movements. In the final sequence of the play, the casting choice became clear as the actors shed character and performed "themselves." Invited by Marmee/Youa to join the voices from the letters and hope chests and enter 2015, the performers each say something they want to do to continue the change, before leaving the stage area. Graham delivered his line with a burst of confidence: "I will take the theater world by storm and become a leading transgender playwright!"

Dance/movement sequences, choreographed by Dani Kuepper, played with the shifts in gender performance—evolving from staid, minuet-like movements in the opening dance, accompanied by the song "Ding Dong Merrily on High," to more frenetic jitterbug movements with "Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy of Company B," and finally, to the exit music and free-flowing movements of contemporary dance with Queen Latifah's "Ladies First."

We struggled to bring the letter writers together in person. Of the students from the first semester Women's Studies course, only a few made it to the performance. The elders we interviewed expressed regret they weren't able to meet in person. "I felt very close to her," said one woman. When Basting asked if she thought they all shared more because they weren't going to meet, she said, "I think you might be right." In future projects, we would build the meeting of generations into the process. We were surprised by how powerful a bonding experience the letter exchange turned out to be. In a cultural moment when media and political forces commonly pit generations against each other, students in Introduction to Women's Studies remarked that corresponding with the elders helped them better understand and respect their grandparents' generation, and gave them a clearer sense of the achievements of the women's movement in the United States. In their final reflection papers, student performers expressed enthusiasm for how performing in a context of collaboration with the elders deepened their understanding of their own paths forward and their performance choices.

WMNS 201

Fall 2014

Instructor O'Brien

The 'Secret Mailbox' Letter Writing Assignment

What is your "castle in the air"? Earlier in the semester, I mentioned I would assign you to write a letter about a seminal moment in your life when you knew what you wanted to "become when you grew up." We will share these letters in a "secret mailbox" (like the one Laurie and the March sisters share in Little Women) with a group of elders at local assisted living homes throughout Milwaukee. In the letter, describe the moment, or series of moments, that culminated into the decision to pursue a certain degree, career, life. Be sure to include details!

These letters should thoughtfully reflect on your locations at intersections of identity and privilege that affect what is possible for your career. By that, I mean, in what ways do certain careers seem more attainable, possible, or attractive for you, given your class, race, gender, religion, ethnicity, age, education, geographic location, historical setting, culture, etc. Make sure to take account of how the intersection of these identity markers factor into your career choices. As a woman, do you have the same options, encouragement, training, and socialization to consider a full range of choices for a career? How might your options and opportunities be different now than they were for woman 60 years ago? And how does your range of choices differ from that of contemporary young men?

As you write, think about ways in which gender has determined roles and opportunities for the March sisters and Laurie in Little Women. Think, for instance, how Jo expresses her "disappointment at not being born a boy" so she could serve in the military with her father. Later, she goes on to "wish" she could go to college like Laurie. While you don't need to write about these connections in your letter, I hope that reading and discussing the book will help you "see" such connections.

The elders will return letters sharing their own stories with you. After you receive a return letter, I would like you to write at least one response this semester. I will collect your letters at the start of class next Friday. You may handwrite or type your letter. Address your letter to your "new friend" or your "pen pal." You may put it in a nice envelope and decorate it however you'd like.

Please make a copy of this correspondence to turn in to me so I can share the letters with Anne Basting in the Theatre Department. As mentioned earlier, Anne is collecting these letters for the Slightly Bigger Women play based on "coming of age" stories. She would like some of these stories to come from our class! What an awesome opportunity to contribute to an artistic performance!