Introduction

A rising number of US college students are participating in study abroad programs with a desire to engage in work with people from different cultures (Keen and Hall 2009; Altbach and Knight 2007). Such programs rely on increasing cross-cultural knowledge and building a collaborative environment. When successful, these programs are mutually beneficial for faculty, students, and communities. What tools are available to build faculty and student understanding of cultures that are different from their own?

Cross-Cultural Competence

Cross-cultural competence (sometimes referred to as intercultural competence) is the range of knowledge and skills that help individuals adapt to cross-cultural environments (Williams 2009). Cross-cultural competence has been measured through subjective changes in an individual's behavior based on exposure to knowledge. Measures have been extended to include external outcomes (Howard-Hamilton, Richardson, and Shuford 1998), such as the ability to complete tasks effectively with others in such an environment.

There is disagreement about the ways to compare subjective and objective measures of building cross-cultural competence, but the literature reflects some common themes. They include strategies that build people's capacities in the areas of knowledge, empathy, self-confidence, and cultural Identity (Williams 2009). Knowledge refers to information about culture and people's behavior. Empathy includes understanding the feelings and needs of others. Self-confidence references the state of being self-aware and knowledgeable of one's own motivations and emotional health. And cultural identity refers to knowledge of one's own culture. Deardorff's Pyramid Model presents the development of these competencies as a system of layers built upon key attitudes in individuals that predispose them to engaging a different culture (Deardorff 2006). These attitudes include respect for others, openness to other cultural perspectives, and a curiosity that allows tolerance of ambiguity. Through additional layers, including access to cultural information and skill development, individuals are able to communicate desired internal and external outcomes from their cross-cultural experience. Deardorff's Pyramid Model was developed for a different pedagogical context. However, layering and coupling internal and external outcomes is conceptually consistent with the pedagogical goals of many study abroad courses.

Building Cross-Cultural Competence: International Service-Learning

In design-oriented study abroad curricula, immersion in a different culture sets the stage for, but does not guarantee, the development of cross-cultural competencies. Recent interest in the intersection of cultural anthropology and design has produced a range of approaches for engaging with different cultural contexts in order to collaborate to solve design challenges. From Setha Low's work (Low and Lawrence-Zuniga 2003), to Beebe's Rapid Assessment Process (Beebe 2001), to IDEO's Human Centered Design Toolkit (2011), processes developed by social scientists are applied to design and planning. A critique of these approaches is that they they are generally extractive. Many are designed to reduce the time commitment for establishing relationships with key collaborators in different cultures, and to meet the needs of often short-term design processes. However, the short-term outcomes can potentially address community issues and approach equity between visitors and locals.

These hybrid "design anthropology" strategies share an emphasis on a cocreational approach. Visitors (design students and faculty) and local people co-articulate the problem(s) to be solved and desired outcomes, and codevelop the course. This process affords interactions and relationship-building that allow participants to examine their capacities in areas affecting their own cultural competency. An emphasis on pre-course preparation defines milestones that provide feedback loops to enhance the process, measurable outcomes, reflection, and assessment, all interconnecting with cross-cultural competency capacity building. This is especially true for international service-learning projects that include the goal of making a positive contribution to a different cultural community and seek a collaborative process.

The following case study offers lessons learned about challenges and opportunities when applying these approaches to service-learning in Ghana, West Africa.

Design and International Service-Learning: Ghana International Design Studio

The Ghana International Design Studio began in 1997 out of linkage agreements between NC State University (NCSU) and Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST). Over 100 participating faculty and students have immersed themselves in a different cultural context than their own.

The majority of participants had never been to Ghana or Africa, and a majority of the students had never been outside of the United States.

The studio was created to directly engage Ghanaian "makers": the artists that still create traditional crafts in geographically specific areas.

Initially, the goal of the studio was for US faculty and students to engage with Ghanaian artists as peers, sharing a common interest in design. Through careful study (hands-on experiences, photography, and journaling) of traditional ways of making in the settings where artists work, US students were charged with creating their own original work, informed by their study. Faculty assessed levels of student understanding through the quality of their finished design work and their visual representations of traditions in Ghana. Final deliverables were completed and presented in the US, not in Ghana. This format maximized time in Ghana for research and documentation, but excluded Ghanaian partners from participating in the culmination of students' work.

In 2010, a reflective survey was distributed to past Ghana International Design Studio participants in order to gather information about their experiences (Boone et al. 2013). The survey focused on several areas, including the most effective learning experiences during the studio. Although students recognized the value of formal educational activities, including lectures and formal demonstrations, they also expressed a desire for more non-formal and student-initiated learning. Additionally, demand for service-learning grew in Ghana with the emergence of several nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) asking for design assistance with local challenges. The convergence of shifting student preferences and increased service-learning demands gave the impetus for reworking the studio into a service-learning model. The 2011 studio marked the first such attempt.

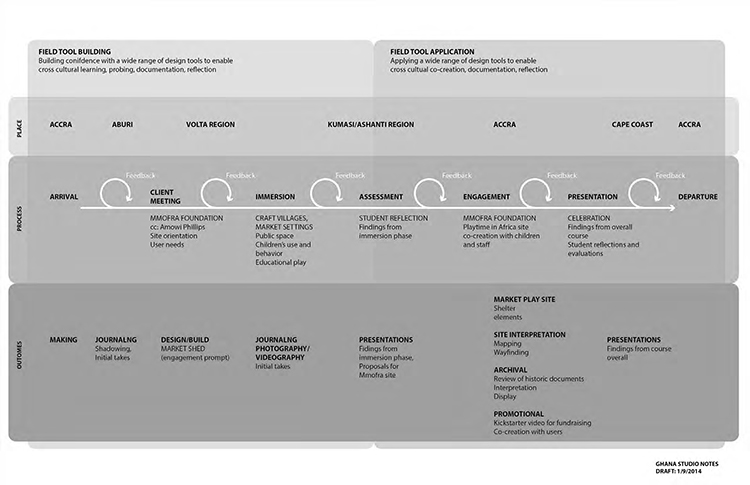

In what follows, I describe experiences with tools derived from studio activities in 2011 and 2014. They illustrate engagement approaches derived from methods for building cross-cultural competence to enhance collaboration between US faculty and students and Ghanaians. The tools are grouped in order to follow the experiences of students that range from transferring information gained about Ghanaian culture, to translating that information into knowledge through various interactions with Ghanaians, to transforming that knowledge into cocreated design outcomes spanning art, design, and planning.

In the beginning of the 2011 and 2014 studio courses, students were asked to embody the spirit of a famous Ghanaian proverb: "Don't say that your mother's soup is the best until you have tasted the soup in everyone's pot." In other words, students were encouraged to transfer their observations (describe and not interpret) about Ghanaian culture and society to documents they could reference later. This was an aspiration; review of student journals and design work revealed student comparisons between their own traditions and those of Ghana. Through NCSU and Ghanaian faculty interaction, students were encouraged to use their impetus to compare cultures as a way to frame questions for future study.

Journaling

Daily journaling was required of all students. Faculty assigned short written and field sketch problems, as well as daily reflective entries recounting student experiences. Students were asked to use their journals to document their thinking, questioning, and process, not just to inscribe concepts and solutions to problems. Faculty reviewed the journals and identified themes for future study. Although most students came from design disciplines, most reported that they had not previously used their journals as rigorously as they did in the Ghana studio (Boone et al. 2013).

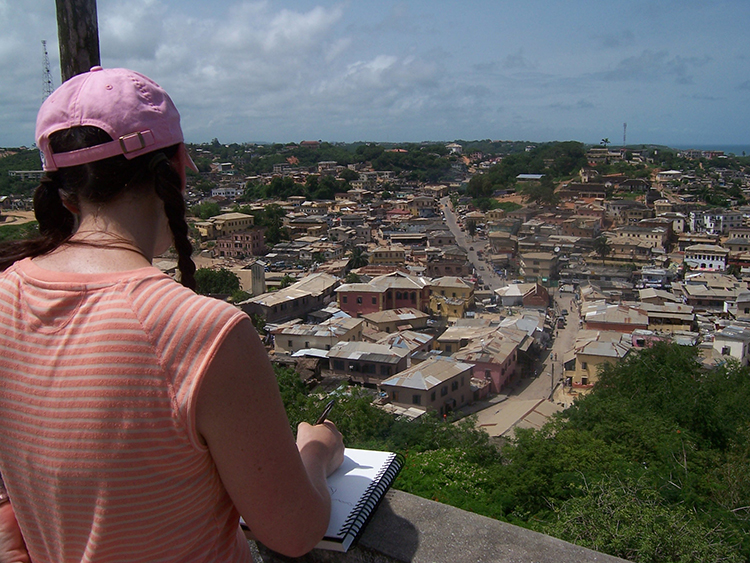

Students identified a commitment to journaling as an important part of the process of increasing their comfort with documenting unfamiliar sites, events, and people. As the studio progressed, journaling was used to document students' experiences in a traditional craft village, as well as the process of making different Ghanaian art and design artifacts. In a field study in a traditional metalworking village, students were not allowed to bring their cameras and relied solely on their journals to document the complicated "lost wax" metalworking technique. In craft villages popular with visitors, artists were accustomed to short-term interactions with visitors, the exclusive use of photography, and the sale of their work. The accumulated experiences with visitors prompted artists to sometimes be defensive and unwilling to be photographed, for fear of exploitation. Some artists reported finding pictures of themselves, their families, and their work online without their consent. However, when they saw students and faculty sketching, asking questions, and listening intently, the artists became more open, descriptive, and attentive to student questions. In some cases, artists wrote and drew their own descriptions of the process in student journals. The depth and clarity of information exchanged, as well as the rapport created between students and Ghanaian artists in field study, improved with a focus on journaling.

Informal Engagement of Key Informants

The course begins with intensive study of Ghanaian culture and society, an introduction to Ghanaian history, traditional beliefs, languages, societal roles, and rituals. At this stage of the program, the course is highly mobile, and builds educational opportunities around different craft village excursions. This involves a combination of lectures, demonstrations, and field study. Students reported through their daily journal entries, as well as course evaluations, that this formal and directed introduction was valuable to their transition into Ghanaian landscape and studio work (Boone et al. 2013).

In the Aburi Hills overlooking the capital city of Accra, Dr. Kofi Asare Opoku has a farm that he uses in order to convey to NCSU faculty and students the complex relationships between Ghanaian spiritual beliefs, cultural practices, and environmental values. Dr. Opoku is an internationally recognized expert in Ghanaian traditional religion. At his outdoor visitor reception area, known as Anansi Okra, he described the traditional relationships Ghanaians had to the land, including the medicinal uses of native plants. He demonstrated traditional greetings, including giving visitors water. After a verbal description of the surroundings, Dr. Opoku guided visitors around the site, explaining the traditional names and uses of vegetation and the relationships between plant communities and cultural practices.

Dr. Opoku's engagement with faculty and students represents an informal key to informant process, whereby a community expert provides outsiders with unique community insights and frames community situations (Payne and Payne 2004). Rather than structured by formal interviews, Dr. Opoku provides formal lectures and guides tours to define and give context to key aspects of Ghanaian culture. Key informants reflect on their own social status and on the level of trust established with outsiders. In Dr. Opoku's case, his status as a university professor and his long-standing relationship with NCSU faculty affords a level of trust between him and the program participants. NCSU faculty and students are able to confirm or deny the veracity of Dr. Opoku's expert knowledge on traditional Ghanaian cultural practices through their own first-person interactions with other Ghanaians.

The students are then encouraged to pursue self-directed studies framed by the Ghana International Design Studio project. Translating broader cultural awareness into more focused study, in order to inform design study, is a critical bridging process between initial immersion and project work.

Direct Observation and "Shadowing"

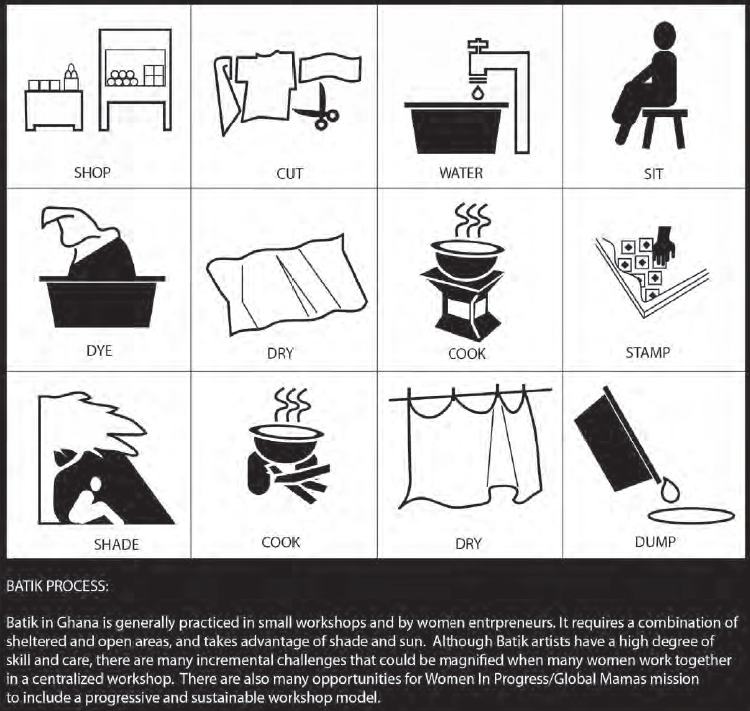

Students were charged with developing concepts for Women-in-Progress/Global Mamas (WIP) fair trade workshop for the batik industry, but they had no previous experience with batik or the cottage industries where the cloth is made. After meeting with WIP, students were encouraged to spend a day observing an existing batik workshop with the components required for their new concepts. Students secured permission to photo and video the site, and spent a day in the facility, attempting to be minimally disruptive (Czarniawska 2007). They observed the entire batik process, discerning issues and opportunities presented by the site, and the needs of the users. By "shadowing" the women in the industry, the students were better informed and better able to generate more directed interviews at a later date.

Interviews

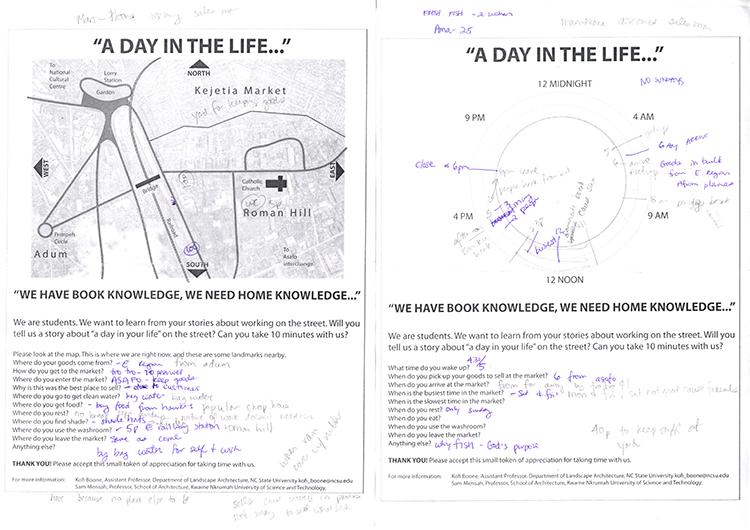

Students who were asked to investigate the environmental conditions faced by street traders in Kejetia Market began with direct observation of market conditions and street-trader locations.

Kejetia Market is the largest open-air market in West Africa, with thousands of market stalls. Street trading is technically "illegal" but if traders pay a "tax," they are allowed to use the streets surrounding the market to sell their wares. The items for sale cover a wide range, from refurbished clothing and electronics from Europe and the US, to seasonal fruits and vegetables, to CDs and DVDs. Over the course of a week, students returned to the market daily, establishing informal relationships with street traders and gaining permission for interviews about their daily lives. This informal experience and relationship building in the market guided students to develop formal interview questions (Crowley 1999).

Students engaged street traders using two tools. The first was a map and aerial-view drawing of the market area, designed to help traders locate their location and the other resources they use on a daily basis (bathroom, food, water, etc.). The second was a diagram modeled after a clock face, used to locate activities based on time of day. The map and aerial view were difficult for street traders to understand and use. However, the clock face diagram was understood and proved an effective means for street traders to document their daily activities.

The use of both tools revealed information about the after-hours issues of street trading, including networks for getting their products, security at night, and the distance that many street traders travel to occupy their spots around the market.

Drawing

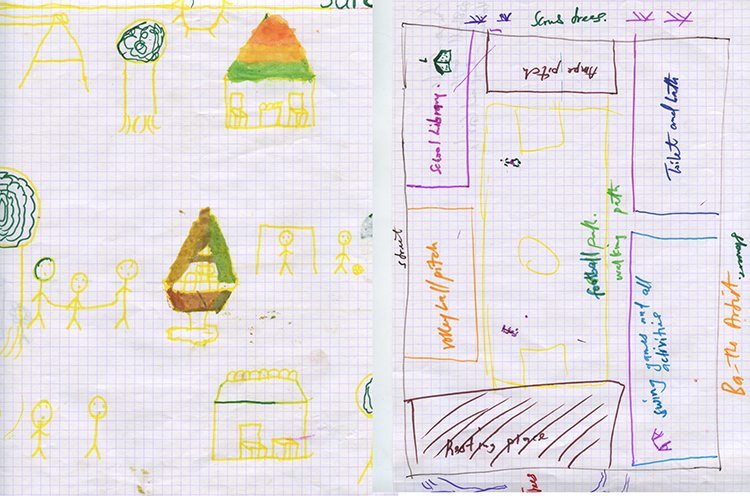

Students working on concepts for revitalizing Asanteman Park in Kumasi organized a children's drawing workshop.

Children were recruited by our Ghanaian partners. The children led a walking tour of the park, pointing out the places they liked, disliked, and wanted to change. Then, the children were divided into small groups to work with teams of our students on drawings conveying their "dream park." The US faculty and students did not sufficiently prepare the drawing exercise and did not get the results desired. Children under 10 years old are concrete thinkers and do not communicate abstract thinking effectively (Roos 1998). Although there were some drawings showing potential park layout ideas, asking the children to draw their "dream park" resulted in many drawings of figures engaged in favorite activities: soccer for the boys, and ampe (a traditional jumping game) for the girls.

Design Games

Students, working with WIP on fair-trade-workshop concepts, translated their observations of the batik process into icons to be used in design games with batik artists (Sanoff 2000). Each icon represented a different use and program element. Batik artists were asked to arrange the icons in patterns that reflected their preferred arrangement of spaces and uses.

Ghanaian artists easily understood the icons and were eager to share their ideas on ideal arrangements. The resulting diagrams were very beneficial to the project. The batik artists conveyed that the process helped them to better understand the project goals and their own programmatic needs.

Traditional Artefacts and Performances

Students toured regional craft villages prior to engaging in their design projects. In Ghana, many cultural traditions are expressed through visual and performing arts. Traditional education is based on apprenticeships, and local art and craft traditions are passed to the next generation through the making of artifacts. Although mastering dance, drumming, and songs is too complex for the duration of the course, understanding the basic symbolism of visual arts traditions is possible.

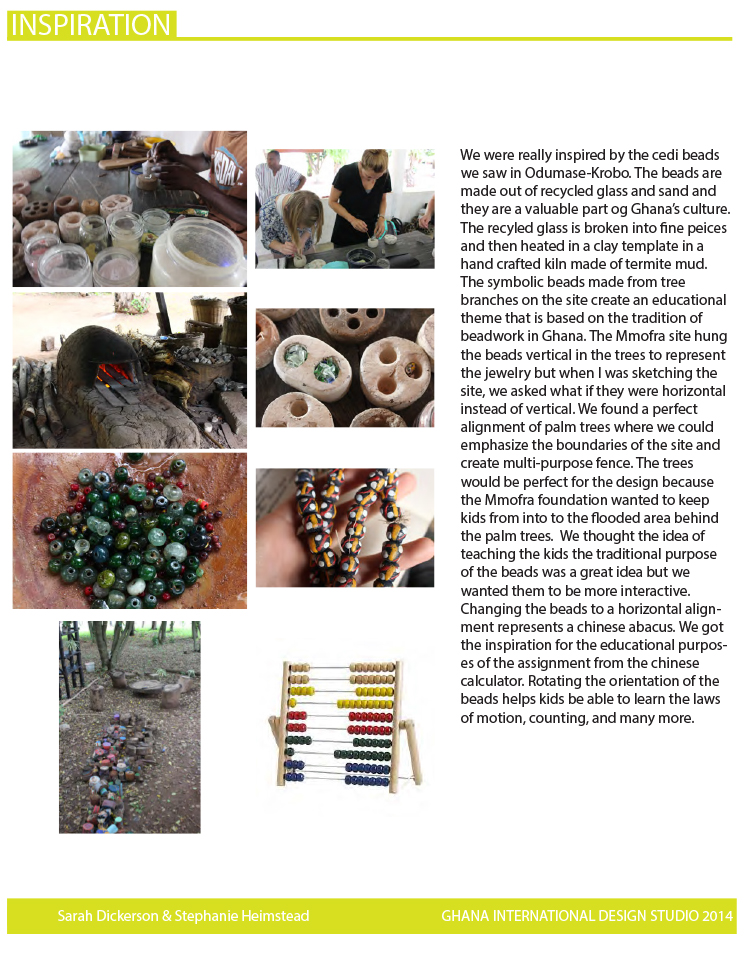

For example, students spent time in Ghana's Volta region in order to participate in the making of Krobo glass beads. Bead making is a local industry that produces artifacts used in rituals honoring the puberty rites of Krobo girls and symbolizes their successful transition to womanhood. The sizes, shapes, patterns, and colors all convey meaning. In an interesting contemporary twist, artists now use recycled glass bottles retrieved from local restaurants, bars, and hotels.

Students began with an overview of the glass-bead-making process, as well as an orientation to the spatial layout of functions in the craft industry.

Then students were invited to make beads, replicating the traditional process.

However, they were encouraged by Ghanaian artists to create their own patterns, color pallets, and symbols. During the bead firing and cooling process, students were invited to participate in a demonstration of rituals using the beads, including traditional dances. By making beads and participating in demonstrations of their associated rituals, students gained perspective on a complex cultural context.

Additionally, by participating in the making of artifacts and performing of rituals, students conveyed their interest in and respect for learning about traditional belief systems.

Informal Encounters: Peer-to-Peer

The Ghana International Design Studio was structured around a mixture of formal and informal learning experiences. Not unlike traditional US-based studios, substantial learning occurred outside contact with instructors. Students engaged in design work with Ghanaians, especially in their age group, learning informally from unstructured leisure activities with their international peers. While working with the Mmofra Foundation on their Mmofra Place/Playtime in Africa site, US students befriended Ghanaian collaborators and engaged in numerous after-hours activities, including visiting extended families, bars, nightclubs, and other social activities.

This type of interaction was discouraged in the early years of the Ghana program due to the unfamiliarity of the nonacademic context of Ghana and the potential risk to US student safety. However in recent programs, the balance has shifted to include more opportunities for students to form their own relationships independent of the formal class environment. This has engendered a higher level of trust between US students and their Ghanaian peer group. Additionally, it has provided a means of learning about contemporary and metropolitan Ghana. The course structure, emphasizing traditional culture and forms of making, has often given short shrift to emerging cultural trends, including the increasing reliance on technology, urbanization, social media, and the influence of global popular culture. The key informants involved in the program tended to shun discussions of these modern influences, assuming that US students were already aware of these factors and that they ran counter to "authentic" Ghanaian values. However, students reported that it was these peer-oriented, contemporary social interactions, that were based on the discussion of things held in common, that forged trust, increased their ability to understand less familiar aspects of Ghanaian culture, and forced them to engage in critical reflection on their own cultural norms.

The last part of the program is dedicated to the application of lessons learned in Ghana to a design project initiated and completed during the program. Contrasting with the earlier and more mobile phases of the program, the last part of the program focuses on design work associated with a single location Faculty and students remain in this single location until the design work is completed. Having transferred initial findings about Ghanaian culture and translated those findings through direct engagement with Ghanaians, students are now charged with transforming places and artifacts in a manner that communicates their awareness of Ghanaian culture and society.

In the early years of the program, this transformation resulted in student artwork displayed in US galleries. However, this prevented Ghanaian participants from experiencing the culmination of program work. The model changed when the studio adopted a service-learning approach. Currently, studio efforts are completed while in Ghana, with results reviewed with Ghanaian colleagues.

Visioning

Students working with WIP developed plans for a fair-trade workshop and batik industry. WIP was losing market share to larger, industrialized batik factories in Asia, and wanted to scale up from the informal backyard batik workshops that are the majority of its enterprise. However, they did not want a typical factory layout. WIP was interested in preserving aspects of craft village culture within their new facility. Using documentation of other craft industry settings, students developed a series of alternatives built around a traditional Ghanaian courtyard setting, arranging elements to frame a multipurpose outdoor space.

The students observed the difficult, and at times dangerous, settings of the batik artists' young children, and proposed an onsite daycare/school setting. The vision plan was used as the basis of feasibility studies led by Architects Sans Frontieres International.

Prototyping

Students working with WIP on new batik patterns to increase market share in fair-trade children's clothing prototyped new patterns and stamping processes. Having documented the range of symbols, color palettes, and themes associated with diverse craft traditions across Ghana, students used them as inspiration for new materials. Students teamed with batik artists and joined them in their cottage industry locations, often in their backyards. Students learned the batik process and produced finished cloth for display and WIP review. This educational process was patterned after lessons learned from IDEO's Human Centered Design Toolkit and emphasized the importance of creating physical mock-ups (prototypes) to refine the process (2011). The production of design prototypes was highly impactful. Ghanaians were able to interact with physical artifacts in the short term. And since the methods by which they were made mirrored their own processes, they were able to offer directed feedback about their qualities, strengths, and weaknesses.

Students working with Mmofra Foundation were charged with developing prototypes for educational play equipment and activities for use at the Mmofra Place/ Playtime in Africa site. Combining direct observations of children playing in a range of Ghanaian settings, interviews with children, as well as design elements from craft traditions, students created a variety of elements and experiences for testing and refinement through interaction with children.

Students hosted a demonstration day at the site where area young people came and tested student proposals. The use of prototypes provided people with hands-on testing of design proposals. This allowed people to provide feedback and insights that guided design refinements.

Conclusion

The Ghana International Design Studio has implemented a range of techniques to enable collaboration between US faculty and students and Ghanaian artists. Initially, the program was designed with the desired output of original works of student art inspired by their careful observation and documentation of Ghanaian art and craft. The numerous repeat visits by US faculty, as well as the intercollegiate partnerships with Ghanaian faculty, established trust between faculty members and favored a more directed and formal educational approach.

However, as course expectations on the part of students and Ghanaian collaborators shifted to include aspects of service-learning, design processes adapted to include an expanded range of engagement and cross-cultural competency tools. Preparing, using, and evaluating this expanded set of tools did impact the structure of the course and reframed the experience into three areas: initial immersion and documentation (transfer), direct engagement with potential users of studio project outcomes (translation), and project delivery (transformation). This new structure was used to modify to the previous one: leveraging the value of immersion in traditional craft villages to provide opportunities for students to learn about Ghanaian culture and society in the settings where design occurs.

With an enhanced set of engagement tools, as well as intermediate steps to foster student comfort with predesign investigation, the course has been transformed to afford meaningful collaboration with Ghanaians. In addition, informal personal encounters have created opportunities for students to learn through peer-to-peer interactions and other social activities, building trust and cross-cultural competence. The development of this competence was observed through the quality of students' transformational work reflected in their journal writings, interaction with Ghanaian peers, and Ghanaian reception of design outcomes.

Future work could extend the nature of cross-cultural engagement into intercultural and transcultural territory. In some ways, the interactions between US and Ghanaian partners has been framed by the focus on traditional arts and culture as a common touchstone for local and visitors interested in "real" Ghana. Rapid urban growth in Ghana is largely fueled by migration from rural areas of overwhelmingly young people seeking a cosmopolitan alternative to traditional village life. A burgeoning concern in Ghana is how to prepare a generation of young people for an urban future in which people are as dependent on information and technology as they have been on agriculture and craft traditions. Kwame Anthony Appiah writes about an emerging global cosmopolitanism that does not deny the specific cultural traditions of places like Ghana, but more fluidly incorporates global influences including media, fashion, and commercial activities (Appiah 2006). In this context, how could US students and Ghanaian partners not only benefit from cross-cultural exploration of traditional culture, but also leverage the lived experiences of US students in urban environments to better prepare the next generation for urban growth in Ghana? Immersion in Ghanaian cities may challenge previous roles that characterized cross-cultural situations, rotating expertise between partners in the interest of forming new global community identities.

Work Cited

Altbach, Phillip G., and Jane Knight. 2007. "The Internationalization of Higher Education: Motivations and Realities," Journal of Studies in International Education 11 (3–4). School Press.

Appiah, Kwame Anthony. 2006. Cosmopolitanism: Ethics in a World of Strangers. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Beebe, James. 2001. Rapid Assessment Process: An Introduction. Lanham: AltaMira Press.

Boone, Kofi, Carol Kline, Laura Johnson, Lee-Ann Milburn, and Kathleen Rieder. 2013. "Development of Visitor Identity through Study Abroad in Ghana," Tourism Geographies 15 (3).

Cromley, Ellen K. 1999. "Collecting Data on Activity Spaces," in Mapping Social Networks, Spatial Data, & Hidden Populations, edited by Jean J. Schensul, Margaret D. LeCompte, Robert T. Trotter II, Ellen K. Crowley, and Merrill Singer. Lanham, MD: AltaMira Press.

Czarniawska, Barbara. 2007. Shadowing: And Other Techniques for Doing Fieldwork in Modern Societies. Copenhagen: Copenhagen Business School Press.

Deardorff, Darla K. 2006. "Identification and Assessment of Intercultural Competence as a Student Outcome on Internationalization," Journal of Studies in International Education 10 (3).

Howard-Hamilton, Mary F., Brenda J. Richardson, Bettina Shuford. 1998. "Promoting Multicultural Education: A Holistic Approach," College Student Affairs Journal 18 (1): 5–17.

IDEO. 2011. Human Centered Design Toolkit.

https://www.ideo.com/work/human-centered-design-toolkit/

Keen, Cheryl, and Kelly Hall. 2009. "Engaging with Difference Matters: Longitudinal Student Outcomes of Co-Curricular Service-Learning Programs," Journal of Higher Education 80 (1).

Low, Setha M., and Denise Lawrence-Zúñiga, eds. 2003. Anthropology of Space and Place: Locating Culture. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Payne, Geoff and Judy Payne. 2004. "Key Informants," in Key Concepts in Social Research Methods. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications Ltd.

http://srmo.sagepub.com/view/key-concepts-in-social-research/n28.xml

DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781849209397

Roos, Gun.1998. "Pile Sorting: 'Kids Like Candy,'" in Using Methods in the Field: A Practical Introduction and Case Book, edited by Victor C. de Munck and Elisa J. Sobo. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press.

Sanoff, Henry. 2000. Community Participation Methods in Design and Planning. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Williams, Tracy Rundstrom. 2009. "The Reflective Model of Intercultural Competency: A Multidimensional, Qualitative Approach to Study Abroad Assessment," in Frontiers: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Study Abroad 18: 289–306.