Introduction

For the past 40 years, Alternate ROOTS has been a champion of, and resource for, artists, cultural workers, and progressive movement building in the southern United States. Immigration to the South has increased dramatically since the early nineties and this boom continues through the present. According to the Migration Policy Institute, four of the five states with the largest percentage growth of immigrants between 2000 and 2012 were in the South (Zong and Batalova 2015). As a network of artists committed to creating work rooted in community, place, tradition, or spirit, it is vital that we are allied with the South's immigrant communities and invested in globally engaged creative practice domestically.

This year, two of Alternate ROOTS Partners in Action projects shine a light on the experiences of immigrant communities in the Deep South. Both artists are themselves multilingual immigrants. Elise Witt, a Swiss-born daughter of Nazi Germany survivors, serves as the director of music programs at the Global Village Project in Decatur, GA. Drawing on her 40-plus-year career as a musician, Witt is working with a team of educators and artists to develop curriculum that empowers teenage female refugee students to navigate their new world with confidence and creativity. In New Orleans, Ecuadorian-born, New York/New Jersey-raised Torres-Tama employs the poetry, visual, and performance art practices he has honed over decades to ensure that the enormous contributions Latina/o immigrants made to post-Katrina reconstruction are not forgotten. Earlier this year, Nicole Gurgel, ROOTS' content developer, spoke with these longtime members about their globally engaged creative practices.

By bearing witness to immigrant experiences in the South, Witt and Torres-Tama's collective body of work resists and complicates the black/white polemic that has long defined both the region and the nation's racial paradigm. Positioning their work within the context of European colonization, cross-Atlantic slave trade, and late-twentieth-century US imperialism, Witt and Torres-Tama reveal the ways in which global conflict and resistance to it has been, and continues to be, woven into the fabric of the South. As artists, their work not only illuminates these issues, but also underscores the power and value of engaging with them through the arts.

Music as Metaphor

A Global Perspective on Harmony

"English is Weird" and "I See You with My Heart." Words and music by Elise Witt.

There are songs that we create, where we bring in words and phrases from every student's culture. I'm working with a group of about 35 students, in which there are probably 80 languages; most of my students speak at least three if not four, five, or six languages. Being a language fanatic, my goal has always been to learn all the languages in the world. Well, at GVP I'm at least adding some phrases in Oromo, Karen, Arabic, Lingala, Kirundi—the list goes on!

We created a song at the beginning of the school year to get to know each other. It's a song of welcome. It was originally inspired by an artist friend of mine, Masanko Banda, who is from Malawi. He told me, "In Malawi, when we greet each other, we say 'I see you with my eyes, I see you with my heart.'" I started thinking about that, and created a little chant using that phrase. On top of that I layered a harmony using the word "welcome." Then students taught us how to say "welcome" in their cultures. And we started layering the words polyrhythmically together to create a vocal collage. This version uses Arabic, Swahili, Hindi, Oromo (from Ethiopia), Kirundi (from Burundi), Pashto (from Afghanistan), and Karen, Karenni, and Chin (from Burma). I love how all of these rhythms can fit together and become that braid of harmony, where we're singing in different languages—they all interweave, and welcome us in. One plus one plus one equals one!

Bearing Witness to Latina/o Immigrants and the Post-Katrina Rebirth

Verde Extra Alien Green. Poem and performance by José Torres-Tama. Click to open pdf of poem.

If we dare to be honest, the first true "illegal aliens" in the Americas were the European colonizers. This beacon of democracy, the United States of Amnesia, was founded on the near genocide of native people, the enslavement of Africans to build empire, and the appropriation of the northern territories of Mexico, from Texas to California, in order to manifest imperial destiny. This is not myth. This is the historical legacy kept in the shadows, but it haunts the nation. Thus, it has a tough time living up to its mythic propaganda as capital of the free world because this troubling history affects the racial divides today.

The country embraces forgetting and urges its people to forget, as well.

I prefer to remember, because knowing the past allows me to better negotiate my future. I dare to carry my immigrant status like a badge of honor, and my mother was brave enough to make the leap from Guayaquil to New York City with her only child, a suitcase full of hope, and barely a few words in English with which to negotiate our passage. Upon arrival into the United States through Miami, I was immediately designated as a Permanent Resident Alien and we were given our green cards to go with the "alien" motif.

Thus, the Latina/o immigrant experience, the underbelly of the American Dream mythology, and immigrants' rights drive the thematic thrust of my work. Post-Hurricane Katrina, I have been on a creative crusade to make sure that Latinas/os and the immigrant workers, who have been a big part of our reconstruction, are acknowledged in the post-storm narratives.

In late October 2005, I met a young Puerto Rican man who told me he had worked for a contractor who promised to pay him and the other 300 men $3,600 for three weeks work. On the day before the big payday, the New Orleans Police Department raided their encampment—a gutted-out abandoned factory where they slept on cots. Acting like Immigration Agents on a raid, the police ran the workers away. This young man was the only one with citizenship papers, and when he confronted the contractor for his rightful pay, he was told that if he wanted his money he would have to go to Birmingham. He had no English to protest this violation and was left homeless. When I met him, he was with an even younger Mexican boy, maybe 17 years old, who was also a victim of this wage heist. Multiply $3,600 times 300 men, and you have more than a million in unpaid wages. This is one wage theft episode of hundreds taking place in New Orleans since Hurricane Katrina.

If we ever have the courage to investigate these violations, the post-Katrina era for Latina/o immigrant laborers will mark one of the most significant periods of labor abuse in this country's history. In the summer of 2009, the Southern Poverty Law Center announced that 80% of the post-Katrina immigrant laborers of New Orleans were victims of wage theft. That is an atrocious number, but not surprising for a city that was once a major slave port when cotton was king.

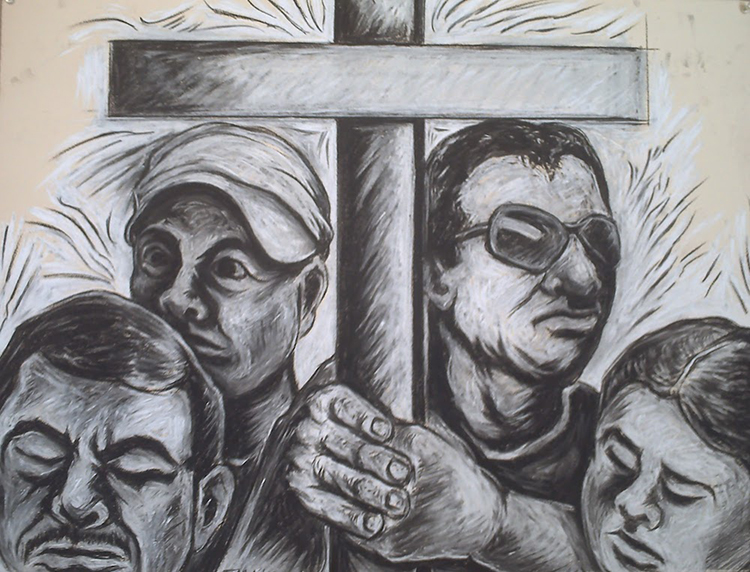

The group that has been doing incredible work to bring this message forward is the Congress of Day Laborers/El Congreso de Jornaleros, and they are actually immigrant reconstruction workers themselves. They have become protagonists and activists in their own fight for human rights because of the oppression they've experienced in the form of wage theft, police brutality, and deportations.

At a Congress of Day Laborers' protest for International Workers' Day on May 1, 2012, the wife of a day laborer gave emotional testimony that her husband suffered a Rodney King-style beating by Jefferson Parish policemen that February. After a week of searching, she finally located him in critical condition at a local hospital. Her husband was in a coma for two months from the beating, and his cranium had to be held together by multiple rods. Because of their undocumented status, they were afraid to report it. This fear and silence is common for immigrants who fear the authorities as much as they fear criminals who target them because they often carry cash on their persons from construction jobs.

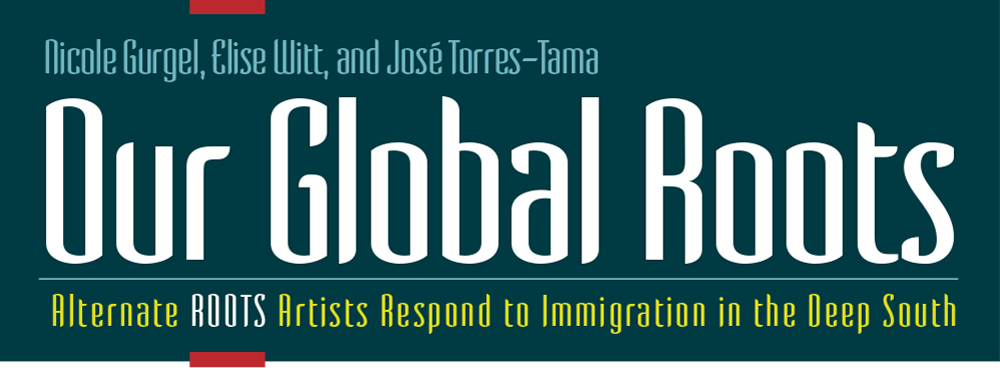

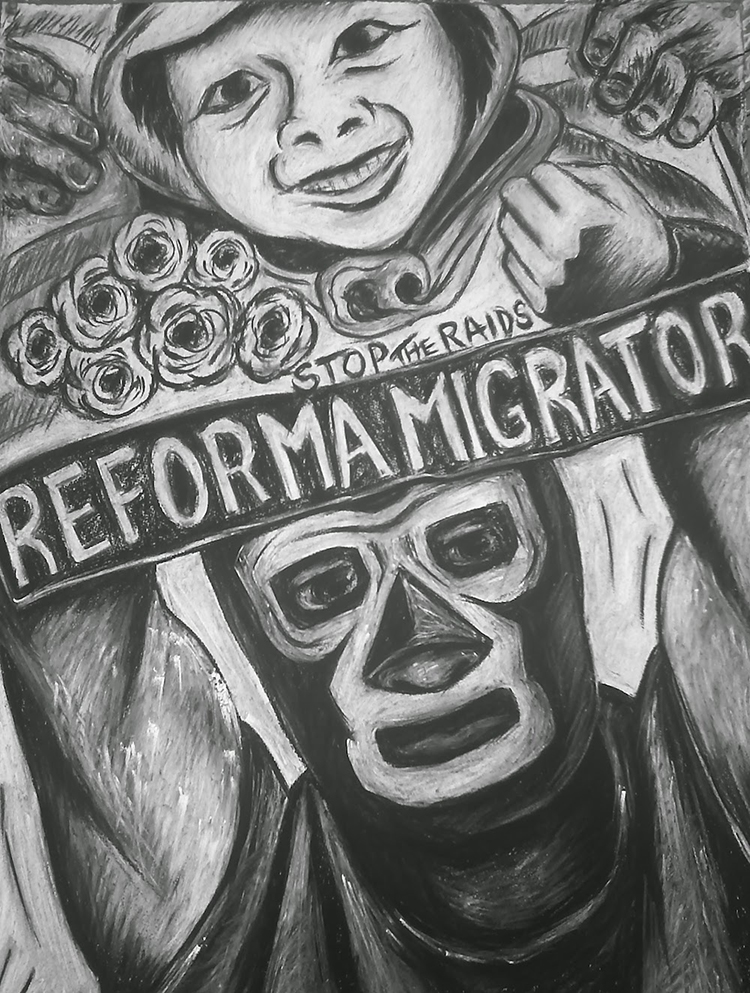

I have been fortunate enough to bear witness to this contemporary civil rights movement, photographing and filming protests since 2010. My performance piece, ALIENS, IMMIGRANTS & OTHER EVILDOERS (2010), is informed by stories of immigrant laborers. With the blessing of the Congress of Day Laborers, I developed a series of drawings and photographic assemblages called Somos Humanos/We Are Human (2013) that chronicles this movement of immigrant workers fighting for their human rights.

I think the best any artist can do is to bear witness. In the Latin American tradition, the artist has a social responsibility to document and articulate the people's struggle—la lucha de la gente. My art is driven by social justice concerns, and I hope that my creative work can serve to expose these difficult truths as we approach the tenth anniversary of the storm.

It's very much inspired by El Teatro Campesino, the theatrical arm of Cesar Chavez's United Farm Workers' Movement, and their tent shows on flatbed trucks in the sixties and seventies. Luis Valdez, El Teatro Campesino's legendary founder, and his troupe went out in the fields and performed for immigrant farm workers, and made the plight of farm workers public with truck performances in front of California union halls. Valdez was actually inspired by Federico Garcia Lorca. Lorca felt that theater was being taken hostage by the bourgeois, and would take his troupe on trucks and perform for gypsy workers in the olive groves in Granada. Basically, it's a means to get the work to the people and into the barrios, and to create work about the heroic nature of immigrants who have been continuously diminished and dehumanized.

We need to engage in a paradigm shift and include a larger population of color that is affected by the lingering legacy of systemic and institutionalized racist practices in the South. The current social justice struggle in the South is more than just a black and white struggle. Latina/o immigrants are being targeted with the same racist vitriol that was once exclusively directed at African Americans. Racism has diversified and other people of color experience the lingering legacy of institutionalized white supremacy that still haunts our black brothers and sisters in the Deep South.

In 2011, Georgia—where Alternate ROOTS is based—passed one of the most draconian anti-immigrant laws in the country. Modeled after Arizona's SB1070, the Georgia law and Alabama's anti-immigrant bill that followed were set up to attack the immigrant community. All Latinas/os became suspects—whether you were with or without papers. If you were a brown Mestizo Latina/o or "Latina/o-looking," the local police in both states could stop you and ask for papers. In Alabama, teachers were asked to become informants and alert officials if they believed their grammar school students were undocumented. South Carolina also joined this new Confederacy, and passed it's own "Juan Crow Law" in 2011, in order to redirect a racist agenda towards Latina/o immigrants. Even more disturbing is that the language adopted is these new anti-immigrant laws resembles language in the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 and 1850 that imposed penalties on those who aided and transported runaway slaves. Substitute "illegal aliens" for "fugitive slaves" and you have a haunting legacy.

If we have any conscience at all, we need to ask ourselves, "What price are other people paying for the freedoms we enjoy as part of the empire?"

I'm a big believer in public activism and taking to the streets to collectively call out these injustices. It's 2015, and having a multiracial president has not stopped the brutality against black and brown men. In fact, the biggest fallout towards people of color post-Obama was actually the brutalization of black men and immigrants across the country. And while Mr. Obama has decided to take executive action on Immigration Reform, this has not come from finally making good on his initial '08 campaign promise, but because of relentless public demonstrations of millions of Latinas/os across the country. Young Dreamers and hundreds of undocumented people went on hunger strikes in front of the White House. Some chained themselves to its iron gates, shaming Obama's administration and it's brutal deportation apparatus. He's deported more than two million immigrants—more than any other president before him. It's a tragic metafiction reality that the multiracial son of an African immigrant ascends to the presidency and becomes the "Deporter-in-Chief."

As an artist who's socially engaged, I'm stunned by the dichotomies that persist in the so-called land of the free. And what we saw at the end of the year was the importance of taking it to the streets and challenging regressive beliefs. We have to question how far we have come when we still have to make a case that Black Lives Matter and that No Human Being Is Illegal!

We are all the people, and we are in desperate need of a major paradigm shift.

Conclusion

These creative, community-based projects emphasize the necessity of a global paradigm when developing publicly engaged art or scholarship with US communities. Globalized US communities are not a new demographic reality, but a continuation of this nation's immigrant history and reflective of its global violences: colonization, slavery, and imperialism. Torres-Tama's work documenting Latina/o immigrants' civil rights battles in New Orleans underscores the ways in which the struggle of new peoples of color in this region mirrors older struggles. Wage theft and police brutality of immigrants, whose legal recourse is compromised by their citizenship status, is part of the legacy of state-sanctioned un(der)paid labor in the South. Witt's work at the Global Village Project highlights the fact that the tens of thousands of refugees who have arrived in Decatur are from exactly those parts of the world where US policies have historically interfered, leading to war, chaos, and displacement. Both artists address the fact that institutional racism and anti-immigrant policies dehumanize entire groups of people whose labor is readily exploited by the same system that forces their migration and vilifies them upon arrival. Witt and Torres-Tama's globally engaged practices speak to the necessity of evolving beyond the black/white racial paradigm so prevalent in the US imaginary, and examining the ways in which the old and continual struggle for civil rights in the South is reflected in the lives of these newly arrived Southerners.

As artists, Torres-Tama and Witt illuminate these truths aesthetically. Witt's music and work at the Global Village Project reflects a complex, multiracial paradigm. Songs like the multilingual "I See You with My Heart" and the playfully critical "English Is Weird" create spaces of radical welcome. Through polyrhythm, what Witt calls "interesting, not totally expected harmonies," and the belief that every voice has something to offer, her music affirms the possibility of multiple truths peacefully coexisting. Torres-Tama employs a vast repertoire of mediums—visual art, poetry, performance, and now a mobile Teatro Sin Fronteras—to bear witness to Latina/o immigrant experiences in the reconstruction of New Orleans. Locating these contemporary struggles within the long arch of US and Deep South history, he underscores the importance of holding the past and present together. In doing so, he echoes James Baldwin: "The great force of history comes from the fact that we carry it within us . . . history is literally present in all that we do" (1985).

Torres-Tama and Witt shed light on struggle, while illuminating a principle that Alternate ROOTS holds dear: as artists, the beauty we seek is bound up with justice. Last November, ROOTS Executive Director Carlton Turner published an essay on Americans for the Arts' ARTSblog, whose title posed the question, "What Is Beauty Without Justice?" Acknowledging that aesthetics has a complex, hegemonic history, he describes ROOTS's understanding of it as, "it's not just where you end up, it's also how you got there" (2014). This understanding of aesthetics—that process is as important as product and beauty devoid of justice is an empty prospect—is reflected in both Witt and Torres-Tama's work. Torres-Tama's Teatro Sin Fronteras almost literally reflects the idea of "it's how you got there." In meeting immigrant communities where they are, this mobile gallery and performance space emphasizes the power of art that is deeply embedded in and accessible to community. Witt "gets there" by building songs collectively, honoring every language and every person in the room. Through music and mobile teatro, these artists forge alliances with immigrant communities, create spaces of radical welcome, and bear witness to the beauty inherent in our struggle for justice.

Work Cited

Baldwin, James. 1985. The Price of the Ticket: Collected Nonfiction, 1948–1985. New York: St. Martin's Press.

Gonzalez, Juan. 2000. Harvest of Empire: A History of Latinos in America. New York: Penguin.

Klein, Naomi. 2007. The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism. New York: Picador.

Turner, Carlton. 2014. "What Is Beauty Without Justice?" ARTSblog. Americans for the Arts. November 19. Accessed February 1, 2015.

Zong, Jie, and Jeanne Batalova. 2015. "Frequently Requested Statistics on Immigrants and Immigration in the United States," Migration Information Source. Migration Policy Institute. February 26. Accessed February 26, 2015.