Social innovation is collaborative action to bring about change in institutions that marginalize collective needs or preserve inequalities (Turner, 2013). Increasingly, design is embracing social innovation in response to the deepening crisis of limited resources and other environmental challenges. The purpose of design for social innovation is to envision and determine ways in which new kinds of products, systems, or perspectives enable those with needs that have been marginalized to collaborate, rethink routines, and go beyond institutional limitations in order to realize a common goal (Turner, 2013). It encompasses a broad range of issues including housing, food, healthcare, education, transportation, poverty, and a sense of community.

Collaboration is one of the key features of social innovation design (Thackara, 2005; Manzini, 2015). In the collaborative process, designers must evolve from being individual authors of objects or buildings to becoming facilitators of change among stakeholders (Siu, 2010; Thackara, 2005). This shift is instructive for community design. Increasingly, scholars and researchers, especially in the west, make efforts to involve users in the design process through participatory tools and methods.

In China, most cities lack citizen engagement due to traditional administrative top-down management. In general, public life is deficient and boring and citizen participation is far from active. Encouraging and facilitating citizen participation is crucial for realizing a sense of citizenship and bringing back urban vitality (Siu, 2010). Design can provide tools and methods, thereby playing a proactive role engaging citizens as activists and change makers.

This paper presents a case study of a collaborative design process aimed at amplifying the everyday ingenuity of people in their living communities. Ingenuity is the quality of being clever, original, and inventive, often by applying ideas to solve problems or meet challenges. The authors of this essay, who also facilitated the workshop, believe that ingenuity is not the exclusive ability of designers but of everyone. The participants' on-the-ground creativity is triggered by the real context of needs, resources, principles, and capabilities. They are the "heroes" shaping a sustainable lifestyle (Meroni, 2007).

Workshop participants are both co-creators and ultimately, the users of the products developed. When we involve users, we ask two main questions. One, how do we perceive the user innovation; and two, how could these "creative seeds" grow and spread more widely?

Germane to the first question, Kretzmann and McKnight (1993) state that the building of communities should be from the inside out. They suggest that to explore the ingenuity of ordinary people, we should wear an "asset lens." They propose asset-based community development (ABCD) as an alternative to a traditional needs-based or deficits-based approach. The ABCD mode stresses community assets including geography, human resource, skills, and space, which help get rid of a needs-driven dead end. As Kretzmann and McKnight write, historical evidence indicates that significant community development takes place only when local people are committed to investing themselves and their resource to the effort. In this paper, we describe how we applied an asset-based approach to our project.

In response to the second question, we explore an approach to scale up these ideas in contemporary communities. We introduce Sweet Home, a self-organized senior club in Qu Yang community with rich local assets including shared space, a pro-active retired teacher, and elderly volunteers. In order to explore how to implement an assets-based approach and exert more impact through design, participants from a university (Tongji University), a commercial enterprise (Marimekko), and a community self-organization (Sweet Home) joined in a two-week workshop. Using textiles as the main material, the participants made a series of micro-changes in their daily environment, which drew great public attention after the workshop.

We also discuss community-based learning. We acknowledge that for a long time, design education in China has taken place in a relatively closed environment -- in the classroom, library, or research lab. Much design knowledge produced by universities is focused on collecting and analyzing data for problem-solving. Community-based learning provides students with a practical context in which to learn how to apply ideas, conceptions, and theories regarding social issues. With increasing emphasis on user involvement, the design outcome can better and more practically meet social challenges and tackle complex and wicked problems. In such an environment, students have to deal with more design issues than shape, material, and color. Both teachers and students must give more attention to the uncertainty of the design process. In order to promote collaborative design education, a long-term mechanism is needed for sustainable cooperation and social engagement.

The result of the project discussed in the paper is a joint force of diverse stakeholders including designers, academics, students, and local community residents and organizations. Both collaboration and participation play important roles as catalysts. The collaboration with designers as well as other professionals provides constructive support and critical suggestions. Had there been no user participation, this story would not have happened. For Marimekko, the project provided a useful context to see how Chinese people, especially ordinary citizens, perceive their western textile branding. Design students acted as inspirations for new ideas and facilitators during the cooperative process. Local people's initiatives are the best prototypes of creative living.

Background

Under the present-day Chinese community agency system, neighborhood committees, sub-district offices, and community centers jointly exert their influences at different jurisdictional levels coupled with a top-down decision making model. Currently in Shanghai, 4,079 streets are organized into 144 communities. Scholars are critical that community development is too tightly managed with low rates of spontaneity (Chen, Cooper, and Sun, 2009). Triggering local engagement and strengthening a sense of community attachment is a big challenge. We describe here a case study of how this challenge is being addressed by one group of community residents and student designers.

The community is one of the most important contexts for social innovation design, creative activities, and services that are motivated by the goal of meeting social needs (Mulgan, 2006). Chinese academics tend to deem design know-how and frameworks for social innovation and change deficient, although design researchers and educators are making an effort to establish an engaged framework, methodology, and practice.

This paper introduces a collaborative workshop held in Shanghai in 2012 followed by an evaluation in 2014. Design practitioners took a proactive path to test how design could contribute to positive changes for an aging community through collaboration between university students and a local, self-organized elderly club. We believe that the project provides lessons for campus-community education practices. It also has implications for aging communities in cross-cultural and trans-disciplinary settings globally, illustrating what design can contribute to public life and communities with or without higher education partners.

Community Self-organization

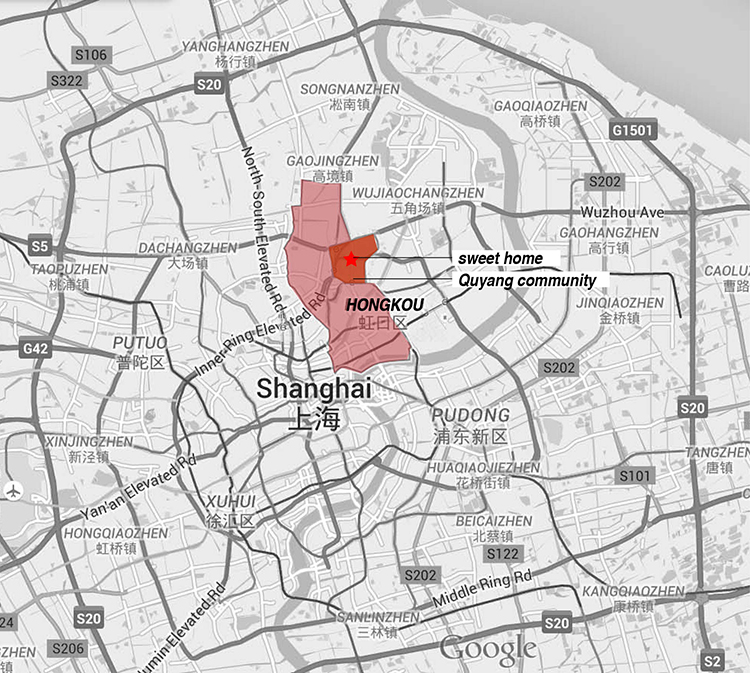

This paper introduces a self-organized senior club in Shanghai, China that local people call wen-xin-xiao-wu (Sweet Home). Sweet Home is located at the top of a 24-story, old-style residential building at No.620 Qu yang road, in the Hongkou district of Shanghai (Figure 1).

Its establishment owes much to a community activist—specifically, a retired teacher, Xiuhua Hu. When she moved into the building in 2010, she found the relationship between neighbors was indifferent and remote. Yet forty-six percent of the building residents were elderly, many of whom needed daily gatherings to enrich retired life. Therefore, she mobilized several community volunteers to renovate an abandoned room into an activity space freely open to all the building's residents (Figure 2).

The community club developed a set of self-support learning programs, including classes in computers, drawing, dancing, and English. Through the program, the elderly exchange their knowledge and skills with each other for lifelong learning. For example, they invited a retired computer teacher to teach others basic computer skills such as Photoshop. By exchanging specialty skills, local people have built richer social capital and closer neighborhood connections with each other than ever before. Most of the elderly living in Sweet Home feel satisfied that they can meet together in a new public space and socialize with their neighbors. Many newspapers and other mass media have reported on its achievements (Zhu, 2013).

Kretzmann and McKnight have stressed that communities could not be rebuilt only by focusing on their needs, problems, and deficiencies; rather, community building starts with the process of locating the assets, skills, and capacities of residents, citizens' associations, and local institutions (Kretzmann and McKnight, 1993). Sweet Home has rebuilt a sense of community belonging by integrating community assets such as spare space, time, human resources, knowledge, and intelligence. Self-organization thus becomes a constellation of local creativity and ingenuity initiated by community intellectuals and follower volunteers as an alternative to top-down management.

An Aging Community Meets Marimekko

Marimekko, a Finnish design company renowned for its original prints and colors, has made important contributions to art and fashion since the late 1960s. For an inquiry into the relevance of its branding philosophy—"a cultural phenomenon guiding the quality of living"—in the Chinese residential environment and to promote school-enterprise cooperation, a Tongji faculty member proposed linking Sweet Home, Marimekko, and the College of Design and Innovation, Tongji University. This campus-community collaboration took place in Shanghai from May to June 2012. The program was a component of the course Urban Reading and Narrative Environments (UREN). In the course, students examine the urban area as texts and images to understand spatial narrative and urban semiology. Students are also required to uncover potential problems and value of people's daily life imbedded in the urban environment.

The six Chinese students and fourteen foreign students from Aalto University and Politecnico de Milano who enrolled in Tongji's UREN course participated in the two-week campus-community program. They came from different design specialties including product design, environment design, and product and service design. In addition, 32 residents from the local community, largely volunteers from Sweet Home, actively cooperated throughout.

With the theme of "small differences, big changes" proposed together by Marimekko and faculty members from Tongji University, the workshop aimed to explore the role of color and emotion in daily habits, traditions, personalities, and rhythms of everyday contemporary urban life. It gave full play to fabric in the community environment and helped to enhance the visual identity of self-organization to be more beneficial to the entire community. The initiators also hoped to discuss the role of designer and local people in the collaborative process and in what ways design can motivate local ingenuity for a better community environment.

Co-creation with Communities

Before entering the community, students received a project background and training in research methods including culture probes and interviewing. They were divided into four groups according to their research interests. Each group conducted its own research with the support of volunteers from the local community. The first week was focused on building mutual trust and identifying problems; the second week, on the co-design process.

The first group used culture probes and in-depth interviews to grasp the experience of people's daily life. Cultural probe is a method of gathering inspirational data about people's lives, values, and thoughts (Gaver et al., 1999). Here the method was used to understand community members' daily activities and identify the places they visit most often. The probe kit included a single-use camera, a personal diary, and guidance on using the material (Figure 3).

After three days, the photos and diaries were collected and became the basis for student interviews with community members, to dig out more meanings from these initial sources. The research evidenced that community members preferred to spend their spare time outside the home enjoying nature and exercise in the parks, and interacting with their fellows. The photos communicate the elderly Sweet Home participants' appreciation of living aesthetics and the importance of family.

Then a co-creation workshop was organized with community members. Provided with fabric, paint, colors, cardboard, and other materials, participants decided to make useful everyday items such as mobile phone bags and volunteer uniforms (Figure 4). The workshop also helped the local community to build a brand identity.

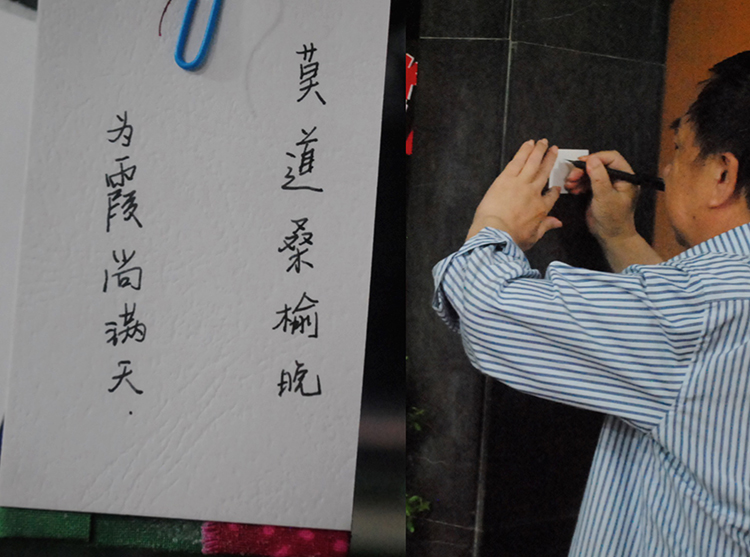

The second group was organized around textiles and employed interviews, matching games, and collaborative workshops. Their task was to apply the North European textile in Chinese everyday life environments and create products to tell stories about the community. Students first collected individual stories from residents to understand their personal values. Afterwards, students identified nine recurring keywords: memory, collaboration, optimism, warmth, organization, happiness, peace, family, and healthiness. In the second stage, students invited the residents to play a matching game associating fabric patterns with the keywords. The selected fabric was used to decorate the old lamps (Figure 5) and mailbox. The redecoration of the mailbox also involved residents' participation. Cards covered with Marimekko fabric were hung and residents were encouraged to write any wish, quotation, or greetings they wanted to express to their families or neighbors (Figure 6). The facade of every mailbox was identified by different fabric according to residents' preferences from the results of the matching game (Figure 7).

Group three focused on photo frames, approaching their task through interviews and storytelling. The group initially had difficulty identifying a way into collaborative design.

After immersive, in-depth, informal chatting with the residents, the students realized that local people's personal stories and living experiences were valuable community assets worth sharing with peers and future generations. By collecting the residents' photos from past decades, dating back to their childhood, the group created "sweet memories"—a simple photo frame covered by fabric and photos pinned onto a board (Figure 8). Residents were encouraged to add captions and texts to explain the stories. The photo wall is still in use.

Group four made curtains informed by interviews and co-design. The idea of making curtains came from local residents because the interior environment of Sweet Home was dim. The students, with the participation of residents, made the fabric into curtains, warming the atmosphere of the activity space (Figure 9).

The four groups produced not only material entities but also gatherings of people dealing with matters of concern (Huybrechts, 2014). Fabric proved to be an effective medium to generate dialogue between designers and users and interactions between students and the elderly (Bjögvinsson et al., 2012). From local people sharing stories to connecting students' design abilities and residents' sewing skills, the students' imaginations were enlarged beyond traditional college design.

After the workshop, senior residents made nearly a hundred sachets with Marimekko fabric and Chinese silk as souvenirs for the foreign students and for the other elderly people living in the building (Figure 10). The program thus triggered local people's creative actions. Design played a positive role in amplifying the ingenuity of the local community.

Project Evaluation

In 2014, the authors conducted a post-evaluation with a focus on the role of co-design through a questionnaire and semi-structured interviews. The authors sent the following to each of the 20 design students and one representative from the local community:

| Please describe your feelings and experience in the process by giving adjectives--for example, happy, disappointed. |

| Please grade the performance of the co-creation process between student designers and the community members from zero to seven. |

| What was the contribution of local residents? |

| What was the contribution of student designers? |

| Please give advice to improve the workshop. |

Meanwhile, in-depth phone interviews took place between a project manager and two Chinese students, two foreign students, and one local resident, for deeper understanding of their experience. Each was about thirty minutes long. The interviews were semi-structured based on the above five questions but varied according to each interviewee's responses.

Eighteen students submitted completed questionnaires. Most said they had a deep impression of the workshop (4.22 out of 5). They had many positive experiences, describing the process as "fun, interesting, helpful, fresh, happy, diversity, satisfied, inspired, and surprising," However, a few students mentioned that it was "disappointing and disordered" because it was "hard to start and get people involved."

Regarding the contributions of local residents, students considered local people as "participators, beneficiaries, and living experience providers," with the most frequent contribution identified as residents' sewing skill. A community representative noted that the local people regarded themselves as mainly expressing user needs and sharing their sewing skills with students.

Regarding the contributions of student designers, community members said that local people greatly appreciated their youth, vitality, and ideas, which brought happiness and positive changes to the community. Due to environmental upgrades in the workshop, Sweet Home was recognized as one of the most beautiful neighborhoods in the Hongkou district in 2013 and won funding for further renovation. The students felt that they made positive changes that enriched community public life. As one student described, some "semi-finished" products that they made during the workshop encouraged local people to continue the creation process after the workshop.

Student and residents offered three major suggestions to improve the workshop: * Provide more icebreaking and alignment with the community during the preparation phase of the workshop since the building of common trust is a key step to co-creation.

| Identify a clear expected outcome beyond merely the process of collaboration. |

| From the residents' perspective, set up the project with clearer time lines so as to reduce disruptions to their normal pace of life. |

Reflections

Community-based teaching is meaningful for research, education, and community development. The Sweet Home workshop was a fresh experience for most of the students and aging residents who participated. Compared with traditional courses, designers were given opportunities to get closer to the design objectives—real residents and built environment rather than abstractions as usual. They could know users' daily life and preferences better. The case embodies four principles:

1. "Assets lens" rather than "needs lens"The case of Sweet Home evidenced that a self-organizing community has many assets such as the potential for good community cohesion and rich activity experiences, which build on long-term social interactions between residents. Undergraduates lack design training in transforming such community assets into positive design elements. In the beginning, some of them felt limited to the design purpose of problem solving and they could not identify the role of design and designers in the process. As one student said:

At the beginning of the workshop, it seemed we were going to change a lot in that community, but when we arrived there, they clearly didn't want to change anything in their organization. They wanted just to decorate their place, and this took away all the meaning of design.

Therefore, we should encourage students to wear glasses with "assets lenses" rather than only "needs lenses;" in other words, use design to stimulate people's ability and make new meanings rather than only to solve practical problems, which is how design education in China has been framed. We believe that the exploration of local assets and opportunities through certain design methods is also beneficial to community.

2. The value of uncertainty in co-creationA participatory project always involves uncertainties and risks (Huybrechets, 2014). As the project manager mentioned, the first half of the workshop was messy "because different people have different understandings and expectations of the project." The students wanted to make high-quality design works that normally are considered functional, beautiful, and eye-catching, while residents preferred more practical uses of the fabric. There was a mismatch of needs bringing chaos and uncertainty to the co-creation design process. This suggests that students need more training to face and deal with uncertainty in design methods and know-how, which may be lacking in traditional design education.

3. Re-adaptation of design methodsProper design research methods, especially in participatory situations, help students explore community assets and facilitate the design process. Different design and research methods employed in this project, such as culture probes and interviewing, facilitated understanding of the users. Such methods were mostly borrowed from western academic contexts. Some of the residents did not fully accept culture probes as they felt it was unreasonable to make them take photos for three days. Unfamiliar or improper design methods may make users feel uneasy and therefore we urge adaptation of participatory design methods in future practices for different culture contexts.

4. Long-term designer-user interactionsLast but not least, how to sustain design participation in a community is a key question for similar projects. It takes time to integrate professional skills and users' creativity. Teaching-based community projects are limited by the amount of time and teaching management such projects require. The next step of our research will be thinking through how to sustain community participation through continuing the teaching process but even more, by opening participation between designers and local people.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the residents of Qu yang community for sharing their life experience with us. We also thank the Hong Kong Polytechnic University and Tongji University for research funding. In addition, we express our appreciation to Marimekko® for making the project happen by providing the fabric.

Work Cited

Bjögvinsson, Erling, Ehn, Pelle, and Hillgren, Per-Anders. 2012. "Design things and design thinking: Contemporary participatory design challenges," Design Issues, 28 (3): 101-16.

Chen, Bin, Cooper, Terry, and Sun, Rong. 2009. Spontaneous or constructed? neighborhood governance reforms in Los Angeles and Shanghai. New York: School of Public Affairs, The City University of New York.

Gaver, William, Dunne, Tony, and Pacenti, Elena. 1999. "Design: Cultural probes," Interactions, 6(1), 21–29.

Huybrechts, Liesbeth. 2014. Participation is risky: Approaches to joint creative processes. Amsterdam: Valiz.

Kretzmann, John, and McKnight, John. 1993. Building communities from the inside out: A path toward finding and mobilizing a community's assets. Evanston, IL: The Asset-Based Community Development Institute, Institute for Policy Research, Northwestern University.

Manzini, Ezio. 2015. Design, when everybody designs: An introduction to design for social innovation. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Meroni, Anna 2007. Creative communities: People inventing sustainable ways of living. Milano: Edizioni POLI.design.

Mulgan, Geoff. 2006. The Process of Social Innovation," Innovations, Spring 2006, 145–162.

Siu, Kin Wai Michael. 2010. "Social equality and design: User participation and professional practice," The International Journal of Interdisciplinary Social Sciences, 5(3), 473–489.

Thackara, John. 2005. In the Bubble: Designing in a Complex World. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Turner, Matthew. 2013. Tête-à-tête. Hong Kong: The Hong Kong Polytechnic University.

Zhu, Minwu. 2013. "Yi-ge-ren-ji-huo-yi-zhuang-lou," Retrieved March 13, 2015, from http://newspaper.jfdaily.com/jfrb/html/2013-11/17/content_1115488.htm.