Introduction

Coupling community-engaged practices with international experiences provides a rich opportunity to achieve and assess cultural competencies within design education. Cultural competency is essential for student learning and for institutions to meet requirements for global perspectives in design education (CIDA 2014). Community engagement in design education has impacted how culture and design are mediated (Angotti, Dobie, and Horrigan 2011) and integrated into practice (Zollinger et al. 2009). Community engagement is essential to student understanding for applied learning. Boyer (1996) states that the scholarship of engagement includes creating a climate in which the academic and civic cultures communicate more continuously and more creatively. Tying community engagement with international experiences provides students with the ability to gain deeper understanding of the global context of design outside of the classroom. To achieve this contextual understanding, students must be immersed in the cultural, social, economic, and political circumstances of the people for whom they are designing (Asojo 2008). This pilot study includes assessment instruments for our method of immersing students in a culture through a joint study abroad and community-engaged experience in order to achieve cultural understanding.

The Program

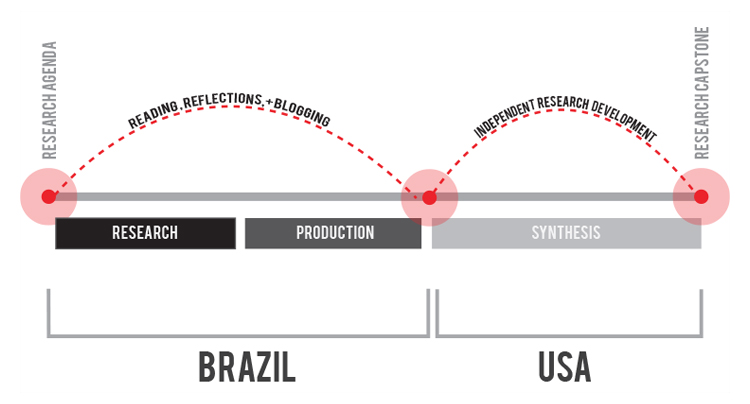

Since 2012, the University of Kentucky, a large public land-grant institution, has offered a Summer Study Abroad Program in Brazil, which includes a series of professional support courses for architecture and interior design students that explore socially responsible design as a means of engaging local stakeholders in shaping their environment and, in the process, building community. Nine students participated in the program in 2013, with eight from interior design and one from architecture. They were a traditional, college-aged population, all females, from sophomore to senior status. None spoke Portuguese. Two of the students had participated in the program previously. I was the faculty member from the University of Kentucky who led the program.

Prior to spending three weeks abroad, students participated in team meetings on campus, Skyped with community partners in Brazil, and began brainstorming design ideas. Upon arrival in Brazil, students worked to design and build a project with the small rural village of Igarai, located 300 km from Sao Paulo. They also completed a sketchbook used to chronicle reflective responses, readings, and observations. Upon returning to the US, students were required to complete an independent research project that was exhibited on campus.

As part of the immersive learning experience and to reinforce the principles of sustainability from an agricultural systems perspective, the group resided at an organic coffee farm near the village. Local community members and leaders visited the farm to speak to students. Students were immersed in the culture by residing on the farm and eating all meals together with the family and the farmers. In order to foster an inclusive appreciation of the community and to generate operational insights into the local methods of construction and the obtaining of material resources, the students visited several sites, including neighboring coffee farms and local businesses. Activities such as coffee tasting, cheese making, and visits to the rain forest allowed the students to gain insights into the local culture, which strengthened the breadth of their understanding.

Engaging the Community through Design/Build

Organizing a community-based design project nearly 5,000 miles from the home campus required overcoming many obstacles. This program was successful in engaging with the community over such distance, and with a short window to complete the project, because of the collaboration that occurred between the community, the students, and myself. The methodology for engaging the village was an ongoing process of finding opportunities, resources, and collaborators that took several years to establish and refine. Building relationships with local stakeholders and finding funding opportunities to support the work were essential.

The program in Brazil came out of my working relationship with a local partner who owned a farm outside of the village. She had a history of connecting community engagement leaders in the United States with many past successful projects. Participating as a designer, I had developed ideas for local public spaces prior to my faculty appointment at Kentucky. The relationship in Brazil developed over two years of community planning and two summers in the community-design process prior to project completion in the summer. Previous projects included a community center on a farm, a community park, and a bus shelter. The success of the previous projects created a positive reputation within the village, access to resources from local businesses, and funding from the local Brazilian government to build the projects. During the summer, design consulting occurred with organizations and social networks, such as a local embroidery group that supports cultural artistic endeavors and provides financial stability to families.

While in the US, collaboration to brainstorm and identify projects to be completed with students occurred remotely via Skype for two and half years. Funding for the projects was a joint collaboration with the community stakeholders and me. Support came in various forms—material donations from local businesses, funding from the local government, support from the school, and participant housing on the farm. This strategy for funding sources was fluid, yet supported in various ways by many contributors.

While in Brazil, the students executed a design/build project—designing and then building on site—selected by the community. The students quickly assimilated to the cultural context, and within three weeks they successfully collaborated with the villagers to identify and create designs for emergent issues that could be addressed during the summer session. These issues included distinguishing between perceived and actual needs, establishing project boundaries, and gathering pertinent information that would enable project completion.

Students and stakeholders established collaborative teams that could further translate the findings from the initial ideation phase into an operational framework that supported theories and practices of Brazilian culture. The teams created a range of interventions, e.g., small design solutions, responding to real-life design issues, with particular emphasis on socially activated design. The limited resources and funding for the project encouraged ingenuity and innovation in approaching design solutions. Community stakeholders sponsored the collaborative projects and supported studio investigations of materials and local resources.

To generate insights into the local methods of construction and the obtaining of material resources, the teams visited sites such as neighboring coffee farms and local businesses. The methods for immersion included interviewing community leaders, working with local schools, and visiting area businesses and farms. Students and stakeholders' collaborative teams developed design interventions. The teams created a range of built designs that responded to real-life issues, with particular emphasis on education design.

The project selected by the community was the small village school. The existing school needed renovation and improved learning spaces. The university students accessed the equipment and teaching tools used by the teachers and established that they were broken, out-of-date, and not supportive of the instructors' pedagogical approach. The students developed questions and interviewed the teachers in order to understand the desired teaching approach at the school. The teachers wanted storage and existing furniture and toys to be repaired. By evaluating the interviews and resources, the students developed designs and a plan to execute the vision of the local teachers. This collaborative, inquiry-based approach allowed the university students to understand the needs of the school and how to effectively design educational spaces through interviews, needs assessments, and observations.

The university students engaged with the local school throughout their time in Igarai. Students conducted site visits and interviews with the school principal and teachers. They conducted a site analysis, held interviews, observed children, noted teaching practices, and met with the teachers in their classrooms. This allowed the community partners to show how they utilized their spaces and resources, and for the students to see how children and teachers behaved within the space. To maximize the limited resources available, the students inventoried existing materials at the school for adaptive reuse in the design project. After these sessions with the community school, the university students met in teams to identify the needs and to begin schematic design.

The design process was greatly influenced by the local resources, e.g., skills, people, and materials. The students learned quickly that they were not able to access a craft store or hardware store in order to realize their design concepts. Guided by local craftsmen, the students worked to create designs in alignment with the materials and equipment available. They worked closely with craftsmen to learn how to fabricate the classroom interventions, e.g., small design solutions, to be able to apply a new methodology of construction informed by a different culture.

Not knowing the language created many obstacles, but also deepened the students' capacity to communicate in other ways. They explained ideas through gestures, expressions, and most importantly, developed their visual communication skills. Sketches replaced verbal explanations, and drawings became the means of communication, which developed their voices as designers.

Assessing the Learning Outcomes

In an effort to explore the effects of community-engaged study abroad, the program was evaluated both qualitatively and quantitatively. Each metric focused on capturing distinct attributes, as will be elaborated, to illustrate the full spectrum of learning. The program was comprised of multiple levels of engagement: student surveys, group discussions, readings, sketching with reflective responses, a design/build project, and a post-program foregrounding individual research. This article focuses on the qualitative assessment, as the quantitative assessment using a survey did not yield sufficient findings.

Readings and Sketching with Reflective Responses

Pedagogically, the course was structured to scaffold learning using various assignments tied to cultural understanding. First, students were required to read articles and book chapters about the history and societal issues of Brazil, community service in design, collaboration, design activism, Brazilian architecture, and culture of place while on location in Brazil. Secondly, students were asked to respond to critical questions related to the reading topics, their daily experiences, and design work completed on site. The questions were derived from the student-learning outcomes for accredited interior design programs. The guidelines for the Council for Interior Design Accreditation (CIDA) referenced for this program were critical thinking, professional values, and processes. The standard for global perspective states, "Entry-level interior designers have a global view and weigh design decisions within the parameters of ecological, socio-economic, and cultural contexts" (CIDA 2014). These criteria are evidenced in the questions we asked students for their reading responses and reflective work:

| What is community and what are its design implications? |

| Describe your experiences working with groups with varying norms and dynamics. |

| How do design needs vary in cultural and social groups with different economic means? |

| What do you perceive to be the contemporary issues affecting interior design? |

| What are the implications of conducting the practice of design within a world context? |

| What knowledge have you developed from your cultural experiences? |

Lastly, the course included field observations to show evidence of the impact of utilizing socially responsible practices. Students documented their observations and field notes in a studio sketchbook. The sketchbook or journal also served as a catalogue of the student's daily reflections and experiences. The exploratory sketching and responsive writing was used to chart learning based on CIDA standards for global understanding and collaboration. These data were analyzed to assess how well students met course learning objectives and how they were personally and professionally impacted by the community-engaged international experience.

Post-Program Individual Research Projects

The rigorous nature of the exploratory sketching and responsive writing captured the intangibles of the experience, and also allowed the student to identify, through reflection, a fundamental research question germane to their personal experience and collaboration. While their research responses took a variety of forms and mediums, the final artifact was both mineable (for future research) and exhibitable (at a fall semester showcase) upon their return to the university. Using the remainder of the summer to develop their research, the students created both the time and space that was necessary to contextualize their Brazilian cultural experience.

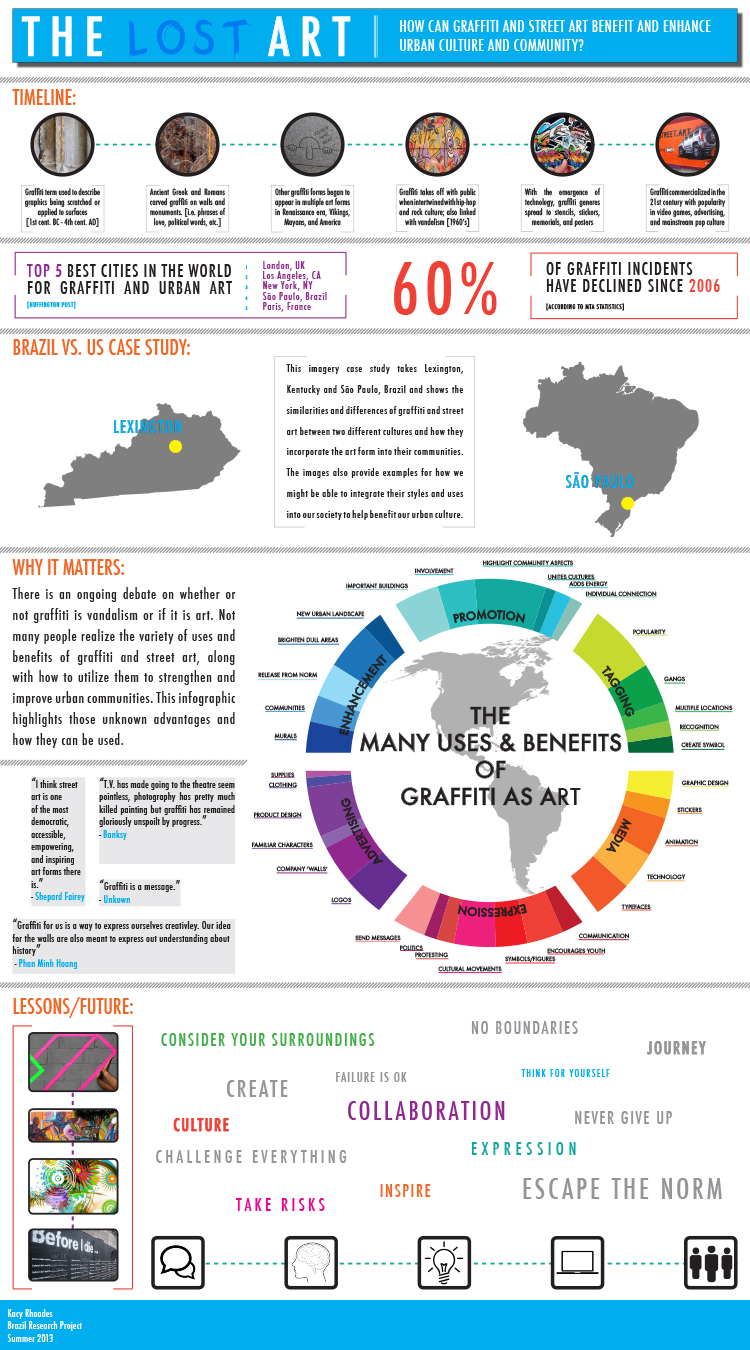

The resulting research projects developed by the individual students were exhibited on campus. Their topics ranged from nature's influence on the built environment to the cultural effects of graffiti. Equally important, the exhibition also demonstrated how socially engaged learning could simultaneously inform the contexts of effective collaboration and learning.

The pedagogical and assessment methods utilized in this program built upon each other. Solely relying on one means of learning and assessment of the final research project would not appropriately reflect the rich outcomes. By layering the assessment of the reading and sketching reflections, the design/build project, and the individual research projects, the program revealed the layers of the experience. The methods also allowed students to gently immerse themselves in their areas of research. Students were not expected to determine a research focus on their first day in Brazil. Not only would that have been shortsighted, it would have robbed the students of exploring their own interests and following their own curiosity. The range of interests were reflective of the diversity of the students themselves. The scaffolding of the learning methodologies allowed students to build a base knowledge of the culture and enabled self-directed learning in the post-program research assignment.

The students had little prior knowledge about Brazilian culture and design. The reading assignments created a base that students could then respond to through the prompts of critical questions. The prompts gave the students direction when reading, guided them to think critically and internalize the meaning of the activities that they did while on site, and created momentum for the work at hand. For design students, the acts of creating, drawing, and making are essential to understanding the built environment. The critical thinking of the journaling gave direction to the drawing and design-build project. The total immersion into the culture throughout the program inspired students to increase their understanding in specific, independent learning.

The success of this scaffolding relies on the willingness of students to be open to new experiences in seemingly new territory and take on independent learning after their return from Brazil. The teacher must, as well, be comfortable with many unknown variables and be able to adapt and respond to changing circumstances. The teacher will not have control over the independent-learning trajectories and must release control over what deliverables and outcomes students might submit for the final project. Although these uncertainties exist, the complexities and diversities in the student work are a great advantage and become a direct reflection on each individual learner's experience.

Student Reflections as Assessment Metrics

Although we can encourage our students to participate in study abroad programs, what learning outcomes do we recognize? Particularly in instances of experiential learning, we need to examine the pedagogical impact of engaging in community-based projects. The student reflective responses illustrated the impact of the experience. Three themes emerged that evidence a transformational learning experience: cultural competency, recognition of community specificity, and design implications. These finding are discussed further in what follows, along with reflection on design/build and the individual research projects.

Cultural Competency

Many students indicated how design could vary in cultural and social groups with different economic means. Students shared personal narratives that capture how their perceptions were greatly different from their actual experiences. For example:

When we first left for Brazil we had in our minds ideas of different projects we wanted and planned on doing. Once we arrived at the school, these ideas totally changed. We began to realize how poor the school really was and that we needed to fix necessities. In my mind I had ideas of cool designed furniture that was modular and flexible. Compared to the projects we have done in school, where money has been no issue and we have designed for middle- to upper-class Americans, this experience gave us a chance to step back and realize that the "needs" for different cultural and economic groups can totally change the outcomes of a project.

The students began to understand how their own values and norms impacted their ability to interpret their surroundings. This provided a transformational learning experience that affected their ideas both as designers and as individuals. Students developed an awareness of their own assumptions and a deeper understanding of how these assumptions impact behaviors and decision making in their own lives. One student wrote:

I have developed knowledge of another culture than my own, in its most basic form. People always "know" that people in other countries and cultures live differently than them, but you never truly know how different people in the world live until you experience it firsthand. You go into the experience thinking, "They speak another language, they eat differently, they look differently, dress differently." But you don't realize that other cultures are actually wired differently. Growing up only knowing one way of life, you don't consider that everyone else probably doesn't function like you do. They don't cram their schedules and run from one day to the next. It's almost humbling, because it breaks down the fact of being human. You start to find what they have in common with you and you connect on those common threads.

Recognition of Community Specificity

Students came to understand how the specific community impacts design. A foundational insight in many of the responses was the importance of relationships and how design and community depend on each other. As one student attested:

Community is the relationships between all people and the world around it. The diverse people and their opinions create a complex and dynamic relationship with the world. The same way that people and designers can change the community, the community can change the people in it. Humans and the community are integrated to create simple existence.

Students stated that the purpose and meaning of design comes from the community it serves. They also realized that design must adapt in order to address current issues. By working with the community in Brazil, the students were able to rethink how and why they design. As this student wrote:

Contemporary design issues include that the architect must rethink traditional terms and concepts of design. Designing something is much more than aesthetics and function. It must be incorporated into the culture. A question to ask the design is what does it mean and what good does it do for the community? It is more than just sustainable design now. The social and economic benefits of the design are a crucial aspect.

Design Implications

Students understood the implications of conducting practice within a different culture. They were able to gain an understanding of how location, building methods, and materials impact design decisions:

Place has a huge impact on design. A location can create or ruin a design depending on if it is built for that particular climate and many other factors. Culture is very different as well; you cannot design for someone unless you understand their specific needs, which may be impacted by the region they are in. In two of my projects, getting to know the people we were designing for totally changed the design of the project.

Students also gained a broader perspective on the design process. They developed a sensibility of how design is truly about the user. Engaging the students in a real-life project, with actual clients, allowed them to understand the specifics of the client's needs and desires. The human-centered design approach was revealed in their writing. For example:

As with any design problem, there is no one solution. As designers, our job is to make sure we solve the problem with the best solution, according to what fits the user's needs. If the solution does not work for the user, then it is not successful design. That's why designers need to evaluate the needs of the client and strictly follow them when designing the solution. A solution that works for one culture, such as modernism with Brazil, will not always function best for another culture. Each culture has their own identity and their specific needs for their design will also be unique. Designers should not be trying to recreate the wheel with every design dilemma, but we should take universal design principles and apply them toward each problem. That way, each design will have similar foundations, but will work for each culture and client.

Design/Build Findings

The design/build projects and independent research supported the learning outcomes of cultural competency, recognition of specifics of community, and design implications of the client, given his/her culture and circumstances. The collaborative nature of the design/build project developed student understanding of the importance of team-based work. One student stated:

After this experience, I have realized that there is a lot more in the world than we can imagine. I have also realized that you can improve a place by even small design efforts. After this experience, design for all has become a reoccurring theme. [ . . . ] I have developed a more open mind towards design and clients in general. Design can be as big or small as you want it to be, and you can truly make a difference in a small way. I have learned to work better in a group and how important teamwork is—especially in design.

Post-Program Individual Research Project Findings

The individual research projects allowed students to develop a research focus on design within the context of another culture. By displaying the work publicly in an exhibit at the institution, it impacted a population beyond the student group who directly participated in the program.

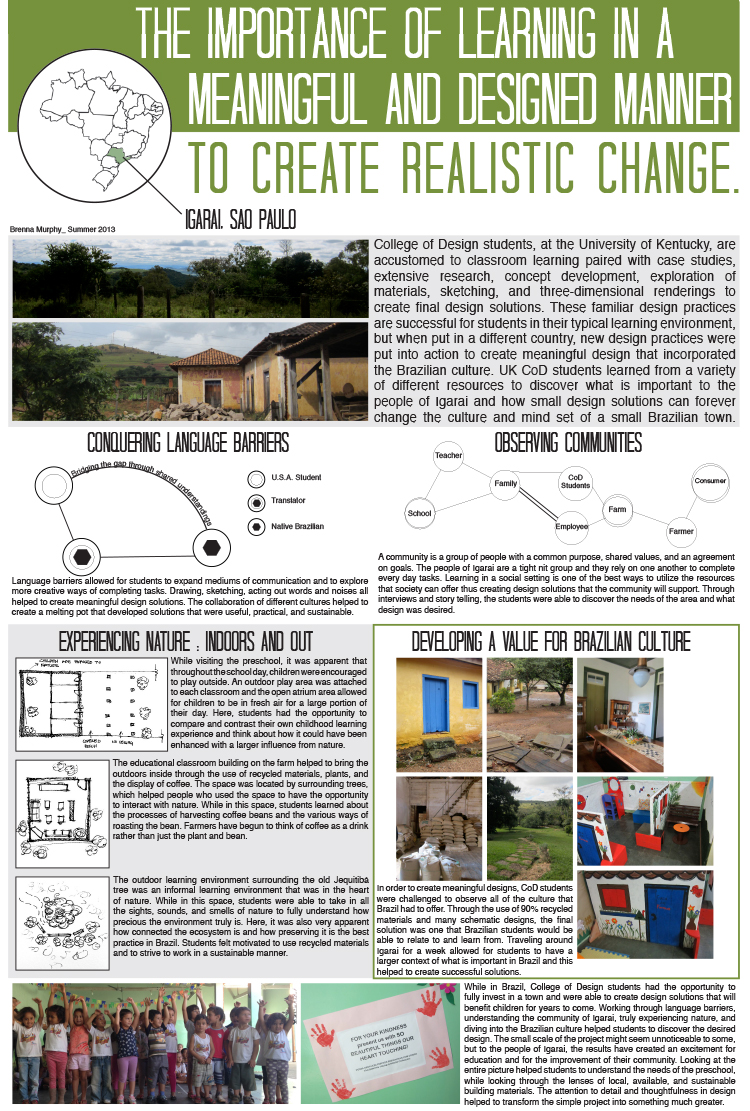

Emergent themes came from the final student projects exhibited on campus. Their ability, or lack thereof, to communicate was evident in the work. One student explored the importance of learning spaces and how they can be translated into meaningful design solutions in order to create realistic change. The project illustrated how she found more creative ways to communicate, using her design skills—drawing, sketching, and building—to manifest her ideas. The role of observational learning was another theme in the research projects. Observing communities, close relationships, and dependence on one another allowed the students to interpret how to leverage resources. One student stated, "Through interviews and story telling, the students were able to discover the needs of the area and what design was desired."

The post-program research projects were a meaningful way to connect the global experiences and contextualize the learning outcomes within the students' own lives. This was evident in the student project about how graffiti art can benefit and enhance urban culture and community. The student was inspired by the urban art presence in Sao Paulo and completed a photographic documentation of street art while in Brazil. Upon returning home, the student looked at the history of urban art in the United States and contextualized it within Lexington, KY. These explorations revealed how the student internalized the experience abroad and was able to contextualize what was learned, in order to apply it critically to understanding her home environment.

Conclusions

The student reflections and post-program projects revealed the transformational nature of the students' learning experience. Experiential learning provided both a broader understanding of the world and a closer and more critical understanding of who they are as individuals. The program developed new priorities in the students' lives and discovery of new interests and career paths. Students exhibited an understanding of working with multiple stakeholders and developed greater multicultural competency. Students became aware of varying socio-economic conditions within other cultures and the implications of sustainable design within different strata. The experiential pedagogical approach allowed students to gain independence as individuals and designers.

The program has effectively illustrated the benefits and impacts of community-engaged design abroad. In a short period of time, the students demonstrated an understanding of design when engaging with local people and methods of collaborating with a community. Because the students were able to create their own new experiences, they deepened their understanding of themselves as individuals and enhanced their ability to critically examine themselves. As one student stated:

The most important thing I learned was that no matter what the situation is there will always be challenges or the possibilities of challenge. I think it's important to learn from [challenges] both as a person and a design student for future life/school/projects. The small appreciation gained can really help us to achieve and make the possibilities endless. The knowledge I developed from [the community in Igarai] taught me appreciation for [other] cultures and communities.

In future research, evaluation of the community perspective as well as the students will be valuable in order to compare and analyze the effects of the experience for all. This would reveal the connection between the learning experience of the students and the value added to the community.

The students developed their own voice and gained self-assurance as fabricators and makers. Their confidence grew as they witnessed their ability to carry a project through to completion. Their critical listening and observation skills became stronger as they became less dependent on verbal communication. The University of Kentucky continues to embrace the program's collaborative context, which, in turn has reinforced the core values of the program. Enduring foundational relationships have been established that continue to benefit the village and the university. The ultimate success of the project is not measured by the built artifact alone, but also by the experience shared by the community and the students.

Work Cited

Angotti, Tom, Dobie, Cheryl, and Horrigan, Paula. eds. 2011. Service-Learning in Design and Planning: Educating at the Boundaries. Oakland, CA: New Village Press.

Asojo, Abimbola. 2008. "Technology as a Tool for Globalization: Cross-Cultural Collaborative Design Studio Projects," Journal of Interior Design, 33 (2), 24.

Boyer, Ernest. 1996. "The Scholarship of Engagement," Journal of Public Service and Outreach 1 (1): 1–20.

Council for Interior Design Accreditation (CIDA). 2014. "Professional Standards 2014," http://accredit-id.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Professional-Standards-2014.pdf.

Gillespie, Joan. 2002. "Colleges Need Better Ways to Assess Study Abroad Programs," The Chronicle of Higher Education. July 5.

Zollinger, Stephanie Watson, Guerin, Denise A., Hadjiyanni, Tasoulla, and Martin, Caren S. 2009. "Deconstructing Service-Learning: A Framework for Interior Design," Journal of Interior Design. 34 (4): 31–45. doi:10.1111/j.1939-1668.2009.01022x.