All artists are alike. They dream of doing something that's more social, more collaborative, and more real than art. —Dan Graham (quoted in Bishop 2012)

While education has always been my day job, I was trained within a traditional studio art practice. For a long time, I imagined "teaching" and "making" as separate. Now I recognize that one constantly informs the other and neither practice is ever going away. At the core of my art practice, I look at what it means to be human, and to attach humans to one another across class, race, and life circumstance—through simple gestures of art. Increasingly those gestures include acts of neighboring, mobility, presence, and creating collective social spaces.

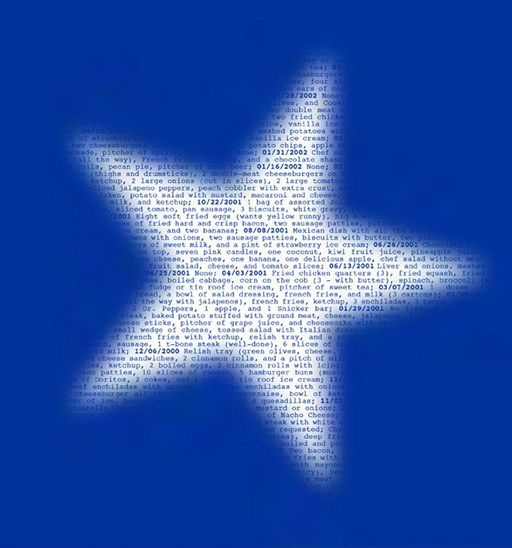

My earlier sculptural works were object and research based, massaging a social issue through a specific anecdote or a small lens. In a body of work called Last Suppers (2004), I cast the final meals of people on death row, hoping to turn a polarizing national debate into an empathic conversation about food choices, and circling back with empathy about the death penalty.

Alongside the nine different sculpted meals, I hung this simple bronze plaque as a reminder that the original last supper was imagined as a gesture of forgiveness, and recognition of our concrete humanness.

When the New Museum of Contemporary Art purchased property on the Lower East Side of New York City in 2003, I was part of Counter Culture, a public art exhibition curated by Melanie Cohn, to introduce the Museum to the neighborhood before it broke ground. Each of the six artists in the exhibition was invited to select a neighboring institution or business to partner with in the creation of a new work.

I chose to partner with the Bowery Mission, both a public soup kitchen and a shelter for men in rehabilitation. The men who lived in the Bowery building ran the public soup kitchen and cleaned and sustained the facilities. I created a mobile pushcart /street store. I referenced the Lower East Side's turn of the century immigrant and pushcart tradition and Claes Oldenburg's 1960s project in that neighborhood called The Store by calling my own project This Store Too. I invested the museum's commission in purchases and exchanges I made with men that I met through chapel services and lunch at the Bowery Mission for several months leading up to the opening of the museum exhibition. I bought drawings, hair, sentences, poems; exchanged t-shirts, coconuts, needle and thread, and silver eating utensils. I altered everything into a saleable product: hair dreadlocks became boutonnieres, poems got silkscreened onto salvaged bits of quilt, and memories and buttons became stitched cloth survival kits and hand-printed rolls of toilet paper. The Bowery Mission preaches core Christian values and that the rehabilitation of a person is financial, physical, and spiritual. Although I did not agree with other parts of their interpretation of Christianity, the three concepts of financial, physical, and spiritual were deeply connected to how I saw myself as an artist and in relationship to my practice.

Everything that I created was then sold on the street. This Store Too remained in operation as a public mobile store for the length of the nine-week exhibition. I operated as a street vendor for eight hours a day and hired three men who were affiliated with the Bowery Mission to work with me. Together, we made all business decisions and bought, sold, and traded while I stitched, sewed, collected, cast, and printed.

The pushcart and the concept of the store lasted for three years, travelling to Miami, Seattle, Syracuse, and then back to NYC. The "business" traded $10,000 in small, handmade merchandise over that three-year period, including lavender and ylang-ylang soaps for sleeping; yellow scarves displayed for my brother-in-law, a Gulf War vet, that his mother and I had crocheted; and objects that reflected hundreds of trades and exchanges. In 2008, the pushcart culminated in an exhibition curated by Patti Phillips at Dorsky Gallery in Queens, NY.

This Store Too was an influential project for me as an artist, moving me outside gallery and museum walls and towards "social sculpture," where dialogue and the relationships that accompanied the store were equal to the object making. The project was grounded in exchange—the economics of an artist's cottage industry—and was for me a new model of collaboration. It veered away from and challenged the models I experienced in academia, with vertical hierarchies and rarified notions of expertise and scholarship. In This Store Too, I created a reversal of who was giving and who was receiving, what had value and who or what determined value, and who held expertise. The work was about food, shelter, clothing, warmth, access, reciprocity, place, dignity, and shame.

To paraphrase Lucy Lippard from The Lure of the Local, architects create space, whereas artists create place (1997).

Feeling a sense of place and the mindset of a college student would seem to be inherently contradictory. Most students that arrive in Syracuse, NY, where I teach at Syracuse University (SU), or anywhere for that matter, probably never think about the needs or issues of that place, nor do they give it a second thought after they leave.

An important outcome of a curriculum that I developed in 2007, for art and architecture students at Syracuse University, was to instill a sense of rootedness and an ecological sensitivity to an inherently transient student population. Much of this work has grown out of my own desire for a sense of rootedness by addressing the landscape and context within which I live.

In the summer of 2008, faculty member Sarah McCoubrey and I declared ourselves "artists in residents" along the shores of Onondaga Lake in Syracuse and gained entry into 1,400 square feet of the contaminated Solvay Waste Beds. While I painted miniature landscapes on recycled photography glass, we taught a studio art class that took as its subject matter Onondaga Lake—at one time declared the dirtiest lake in North America. Onondaga Lake, until recently, was the elephant in the room. At that time, except for a few pockets of environmental scientists, neither the city nor the campus talked much about the lake. Yet the lake tells the history of the city through its plant and fish population, industrial waste, sewage, and salt—the iconic resource of that city. In the Lake Project class, students created scenic viewing stations and used performances of washing, rowboat rentals, and interviews with lakeside joggers' to explore, through their senses, one of the city's most telling landscapes.

In 2007, Syracuse University's then-Chancellor Nancy Cantor invited me to propose a project that would bridge the campus and the Syracuse City School District, with its high school graduation rate of just 48% and 31 different languages spoken. When I visited the city high schools, in order to talk about the University and school district sharing curricula and resources, the schoolteachers and administrators' overriding complaint was about lack of physical space within the schools.

Josef Beuys, a German conceptual artist in the 1970s, said, "Sculpture is not an object or a thing —but is how we as artists can mold and shape the world in which we live" (1974, 48). In 2007, I developed a curriculum named after this concept—"New Directions in Social Sculpture" (MLAB Builds!)—in order to address the lack of space and of arts education in the crumbling city schools. This was the first time in my teaching that I specifically used art and design to address real-world social concerns.

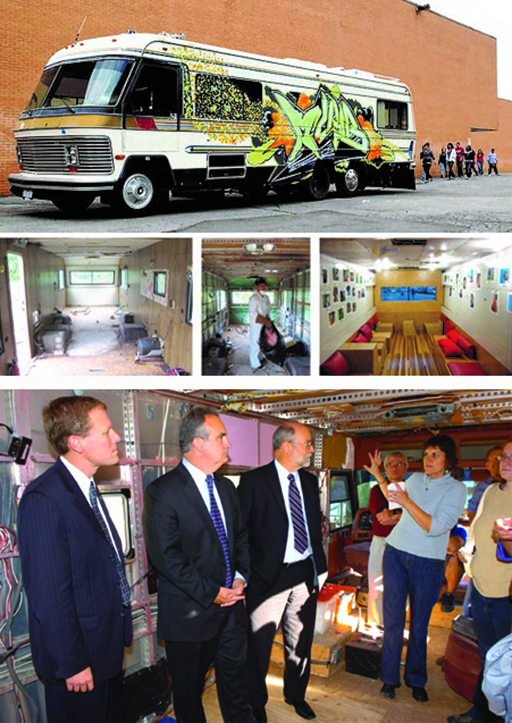

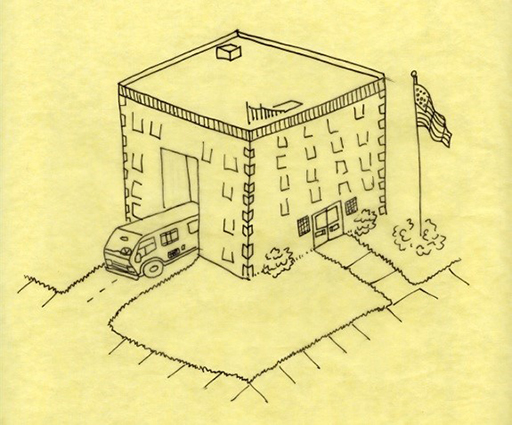

MLAB Builds! began with the purchase of a 1984 American Eagle RV. With a total of $30,000 from two grants, my yearlong class of nine students gutted, renovated, and then programmed this used RV into a mobile digital lab, poetry library, and community gallery in order to offer arts education to city schools. With a set of cameras, a set of art and poetry books, and two graduate student teachers, the refurbished MLAB has travelled to 12 city schools a year—over three years offering art and creative writing programs to elementary, middle, and high school students.

MLAB created a liminal zone—a new geography—attached to, but outside of, the school building. It was a threshold space that moved from place to place, sharing a single set of resources, triggering new creative experiences by being both within and outside of the traditional school classroom. As a design model, I adapted what the artist Doug Ashford (a founding member of the 1980s artist collective Group Materials) introduced me to, which is that everyone does everything. The assembly line production of the scrap floor exemplified this concept. We created an open, transformable classroom space where students were able to perch at different heights on stools that also became countertops using drawing boards that reversed as cushion seating. The "classroom" itself was decentralized, with no central place for a teacher to sit, instead encouraging individualized work or one-on-one or small group dialogue.

In Syracuse, NY, at a private university within a relatively depressed city, there is the assumption that one side of the population is privileged and therefore has the capacity to give, but does not have needs itself. The other side is poor and would be the natural receiver. I would suggest instead a relationship of community and reciprocity—or the Senegalese concept of MBOKK (family)—we all exist as human and therefore need (and have skill sets) equally. Our community and our collaboration could begin from this place. I learned about this concept from a sculpture major and Honors College student, John Cardone '10, and felt it articulated my experience of collaboration with the three men from the shelter on the Bowery and describes the collaborative design model of 601 Tully—the final project discussed here.

University backing is a necessary backdrop to this design work. Chancellor Nancy Cantor, a chief supporter when this work was created, articulated a mission of "scholarship in action," which encouraged collapsing the borders between city and campus in favor of a citywide campus partnership and learning laboratory. She reinvigorated the historical American college tradition as institutions for public good. There were three core initiatives as part of her city engagement. The Near West Side Initiative involved a reinvestment in one of the poorest neighborhoods in the country, the West Side of Syracuse, with green infrastructure, arts, and education. The Connective Corridor was essentially a cultural map and bus route linking campus to downtown. Say Yes to Education was an investment in the city schools, both socially and educationally, with the promise of college scholarships to young people for low-income families. My interest was to create one project that embodied the missions and goals of all three initiatives as a way of investing in the city and capitalizing on the new sources of funds that were made available because of these initiatives—but not necessarily directly to artists.

Mel Chin, the conceptual contemporary artist and sculptor who created the seminal ecological artwork Revival Field, introducing plants for soil remediation, said a decade ago that "ecology is the new sculpture" and, more recently when we spoke, avowed that "plants are the solution for the future." Gordon Matta-Clark, also a sculptor in the expanded field, uses architectural interventions in neglected urban areas to reveal unjust social conditions. While many architects (and artists) function in the public realm through the structures they build or actions they take, Matta-Clark works reductively to reveal the (overlooked) site as it already exists—through cuts, frames, lenses, pinholes, and neighborhood and building selection—allowing us to see it again or more fully.

601 Tully, named after its street address, was an abandoned residence on the West Side of Syracuse that I renovated, with college students, into a neighborhood art museum and center for education. Both Mel Chin framing toxic soil and Matta-Clark drawing a circle through which we view urban blight, help to reveal an existing site. I would add to these broadened definitions of sculpture, neighboring. In the case of 601 Tully, it is the collaboration and gathering of the mixed expertise of neighbors in order to invent a new space that is porous and in a state of flux, and also becomes an anchor in an otherwise transient neighborhood.

Although 601 Tully is characterized as an architectural renovation project—and was in fact cross-listed as a Professional Practice architecture class and as a sculpture elective at SU—601 Tully was developed, conceived, and executed through an artist's lens. At the groundbreaking ceremony for example, dignitaries, deans, politicians, and school kids were handed paper, pencils, and drawing boards. I led the crowd of 160 people in a blind contour public drawing lesson—an observational drawing exercise typically taught to art students—which allows for deeper perception merely by disallowing the artist to look at their paper, forcing them only to study the subject that is before their eyes. Through much of the renovation project (to the discomfort of the contractors), I intentionally did not predetermine what the building would become, but rather let it take shape in response to the evolving desires of the neighborhood. The second week of class, we held an informal focus group, with the college students learning from the residents by asking: 1. What is the history of the building? 2. What is the history of the neighborhood? and 3. What did they envision this abandoned building becoming?

On February 4, 2010, with the help of project architect Anda French and Home Headquarters, the class went before the city zoning board in order to make the case to change the zoning of 601 Tully from a residence to a small business. The city zoning meeting was more like a community barn raising—with hundreds of signatures collected in favor of the redevelopment of the property and impassioned speeches given by neighbors, including the local grocer, high school guidance counselor, and high school kids.

601 Tully began in 2009 with the purchase and renovation of an abandoned residence on the West Side of Syracuse, the ninth poorest neighborhood (by zip code) in the country. The 1,900-square-foot abandoned home across from a middle school and a city park had become a local drug haven. Over the course of seven semesters, and now in its fourth year of programming, my rotating college classes designed, built, and programmed this house as a contemporary arts and education project space that links university, neighbors, and artists in the coproduction of culture. Whereas MLAB was about creating a liminal or threshold space for learning—a mobile classroom that shared a limited set of art supplies and books with a maximum number of student while using geographic shifts as creative prompts—601 Tully is entirely about being in place, providing a social and public anchor space in the neighborhood, and permanence. Whereas MLAB could reach nine hundred different K–12 students in an academic year, 601 Tully has 4,000 annual visitors; many of them are repeat visitors who come in every single day.

601 Tully is two miles and 31 languages from campus. I moved my teaching to this building, bringing along 76 students in the design/build phase, several MLAB alum, and several extremely wise high school students from Fowler, the local school. In the first two years we re-zoned, re-designed, and built and now, in the fourth year, we sustain 601 Tully both as an ongoing curriculum, a living sculpture, and a small neighborhood art museum.

My goal was to create a public space that was porous and could evolve to define itself —where people with varying backgrounds and agendas could exist together—with art, education, ecology, and job creation at its core. All programs at 601 Tully are free to the public and grow out of a partnership between artist, neighbor, and university.

Each semester we invite a new artist to work in the space and help them find local partners. We ask them to imagine the building itself as a living sculpture. Dan Sieple, an American artist based in Berlin, created a wooden bird feeder from 10-ft lengths of 2 in. by 4 in. wooden planks that he notched together. They traversed 31 of the neighboring property lines on Tully Street. Staten Island artist Tattfoo Tan, with third graders from nearby Seymour Dual Language Academy, created a Nature Matching System mural linking color and nutrition (phytonutrients). Funded by a grant from the CNY Community Foundation, my Fall 2013 college class developed the curriculum.

The actual and conceptual life of a butterfly was the departure point for 601 Tully's inaugural exhibition, which placed humans and butterflies together in a microhabitat inside of an art gallery. Michelle Molly, a grad student in the class, describes in the exhibition panel that the Butterfly Effect exhibition introduced the 601 Tully site not as an object in the field, but as part of the field, and embodied the philosophies of 601 Tully as a sensitive, dependent ecosystem operating between university and neighborhood ecologies. 601 Tully is a concrete site, a curriculum, an idea, and an artifact of collective experience that, like the butterfly effect, can appear at times random or out of place, but is actually part of a complex, interlocking system.

The centerpiece of the exhibit was a living butterfly habitat constructed by students from my 2010 Artist and Social Profit interdisciplinary class, using local reclaimed materials.

As artists, we are able to move into and between interstitial spaces in a way that is mostly nonthreatening; art practice can be peaceful and ecological and stir the senses. Art is observation and seeing, imagining and re-envisioning—which I believe is what creates change. Privilege is invisible to those who have it. If we make privilege more visible, we may move toward a more just society. I encourage artists/students—whose work is in part defined by making the invisible visible—to make this a part of their artist/citizenry.

When asked to measure the value of an experiment like 601 Tully, I think in terms of relationships, of human evolution; a return to what it means to be healthy and human and how we affect people's ability to fulfill that. Have we restored the physical, the financial, and the spiritual—have I offered that to my students and to our neighbors—and is that even a relevant goal in the eyes of a university? Our success stories at 601 Tully could read more like personal testimonies—from the 104 students who continue to recognize this class as a central part of their college education; to the local high school students who chose college rather than the marines, gangs, or running away; and the neighbors who are now employed by the arts space. What it means to be human and to be a university, should be measured in part by how well one acts as a good neighbor. If a university thinks about its own butterfly effect, it could realize that even if it chooses to pull up its drawbridges, it still is a part of the living ecosystem that makes up a city and a society. I simply believe it has cut its wings.

Conversation between Marion Wilson and Rick Lowe, September 9, 2014

MARION WILSON: I've been thinking a lot about an idea I call neighboring. I don't know if this is a word that you've thought about, but it may best describe 601 Tully's role on the West Side.

Joseph Boyce says that "everything is art and everyone is an artist; thinking, experience, is a social sculpture." Mel Chin says, "Ecology is the new sculpture." I'd say that "neighboring is a new form of sculpture," particularly as it frames 601 Tully, Project Row House, Watts Tower, and possibly the Re-Build initiative that Theaster Gates started in Chicago. Can you talk about neighboring as a generative practice or idea?

RICK LOWE: I think that all of those things are kind of connected. Neighboring implies that there is connection with people that are around a certain place. It is different than community; the connection should be based somewhat on full participation. There is a lot of creativity in saving one's environment and there is certainly a sense of ecology that wraps it all together. Looking at the diversity of people within a particular place and thinking of them as neighbors signifies something that is more sustainable than otherwise.

There have been people saying this for a long time. There has been discomfort with isolating art out of its own place by itself and realizing that in isolation is probably not the most healthy place for art to survive. It has to survive within a context—other aspects of life. I would use the term—you have to be good neighbors because of wanting a sustainable possibility for the future.

MARION WILSON: Great. Yes. One of the ways that I began to think about being a neighbor was in opposition to being seen as an institution. Every step of the way I have had to be cognizant of how and who I was representing (as an employee of the University), which even led to certain design decisions. The college students needed to be aware that, in a sense, they were uninvited guests in a neighborhood that was not their own, and how that would feel.

We built trust by showing up and working there every day, slowly remaking the building at 601 Tully. I think people began to see us as less an institutional arm of the University and more as people in the neighborhood. A different kind of trust was built. For many students this experience was life altering. That is not necessarily something that I had imagined in the beginning, but it clearly was something that allowed all of us to function much more meaningfully in that context.

RICK LOWE: You are saying in the context of an institution or the context of the neighborhood—it was a hindrance?

MARION WILSON: In the context of the neighborhood. The idea of an institution is very different than the idea of a neighbor. Syracuse University is an institution engaged in the large-scale endeavor called neighborhood revitalization. I think that when I went into the West Side, even though I came as a faculty member and clearly a person from the university, which is one of the largest employers in the city (although most people on the West Side had never been on the campus), it became apparent even in our design solutions that we were functioning in an anti-institutional way. Our relationships were key; we needed to slow down the pace at which we worked.

Now when I talk to the middle school principle right next door, although we have different employers, we share the same physical corner so we naturally have a different relationship. The institutional boundary, merely by the fact of my being there, is erased. Our context becomes more of similarity and less of difference. I think this is much more effective. Being treated as a neighbor felt like a privilege that we have earned.

RICK LOWE: I think you are using the term neighboring —and particularly putting institutions in that context—in a way that allows for a certain kind of vulnerability and a different kind of empathy with people in the context that you are in. It is hard for institutions to do that. It's hard for institutions to show vulnerability. They can show empathy and they are probably more likely to show that than vulnerability, because they are so committed to sustaining themselves and to sustaining an identity that can't do that. I think that is really what good neighbors do; they empathize with one another, and also understand and allow in the act of being as vulnerable as each other, because you are all kind of relying on each other—neighbors. You are not self-sufficient. I mean, you can be a neighbor by proximity but being neighborly is very different.

MARION WILSON: Yes, and you succeed and fail together . . . I like what you said. You know, there has been a lot of talk about community and redefining community, not using the word community —what does it mean, does it have an "other" implied, and I think it is a word that I don't use anymore. I talk about neighboring more than community building. I am more comfortable using the word neighboring. I think it has more possibilities as an idea.

RICK LOWE: I haven't used the word neighboring, but I have constantly considered the differences between neighborhood and community. People use community a lot, but community is such a broad thing. I think that neighborhood puts things in a little bit of a frame. And it offers a possibility of a kind of vulnerability that I was talking about earlier, because it's not a defined space, although there is a spaciousness to it. Communities can be around ideas and thoughts—those are great associations and ways to come together. The difference—neighborhood is a little more specific about a particular space and how you relate, communicate, and operate within that space. There is a different kind of sensitivity that comes along with it. So, how do you deal with the people? Then you are within a neighborhood.

MARION WILSON: I really charge the university to recognize that whether they are in small cities, or any city, or any town—they share the same struggles that a city or a neighborhood struggles with. They must recognize their shared collective responsibility towards that, which is very different from the traditional definition or role of scholarship. It is within the early mission of a university to act as an instrument of public good. A university should have a relationship to the public—and not just a relationship that reinforces themselves as the experts—that's not a relationship. I think that universities as systems, their structures, and traditional scholarship move us away from this. This is a constant challenge for me. What kind of neighbor are you going to be; do you engage in reciprocity—these for me are both scholarly and ethical questions. What kind of citizenship and social justice are we practicing and participating in?

RICK LOWE: My sense about universities is that for the most part they function more from the framework of community than neighborhood. I say that in the sense that—there are communities of universities and academic communities, and how things happen academically—in those conversations happening across the globe, right? So people at Syracuse University are in conversation with their community of academic disciplines across the world. But, it is not a sense of gravitating towards being a neighbor is the place that they are. I think they function much more comfortably in the context of community than neighborhood because they don't have any real commitment to neighborhood. I think that is just an expensive hub—the world that we live in now with technology, we have what we call citizens of the world now, right? They don't really even think of that as their neighborhood, because they don't have a neighborhood, they don't need a neighborhood, because they have a community. Their community is this network of associations throughout the world. So, they go into their homes and where they are and they meet their best friends that are in a different state or different country, and they communicate with them that way and they travel to see them. There is no real sense of a need for neighborhood in the kind of modern, technological era. I think that it just kind of eats away at our ability to have some of those key elements of what I think are required for good neighboring, and that is being empathetic with your neighbors and knowing who they are.

MARION WILSON: And it's hierarchal. The further you are away from your own neighborhood, the more esteemed your scholarship might be seen.

RICK LOWE: Absolutely. I find it amazing how universities are doing great research and spending incredible amounts of resources in places that are across the country and the world, and similar convictions are right next door to them. They don't see it. They don't get it.

MARION WILSON: I also want to talk with you about education, and I want to quote Paolo Freire. I think you have said and I have said, there are always kids around. There are always kids around 601 Tully. No matter what kind of event, no matter what, there are always six or seven kids that are right there and I want to tease out their experience with artists in this kind of setting; and how that experience functions in relationship to their more formal school setting. I know you have mentioned the constant presence of neighborhood kids at Project Row Houses.

RICK LOWE: Oh, yeah.

MARION WILSON: Paolo Freire, the Brazilian scholar and educator, wrote Pedagogy of the Oppressed, which was important to me when I first started teaching in New York City. As Richard Shaull writes in his Foreword, "There is no such thing as a neutral educational process. Education either functions as an instrument that is used to facilitate the integration of the younger generations into the logic of the present system and bring about conformity to it, or it becomes the "practice of freedom," the means by which men and women deal critically and creatively with reality and discover how to participate in the transformation of their world." ([1968] 2000)

That is kind of a lofty way of talking about the possibilities for school kids hanging around 601 Tully and seeing the practice of a different kind of education. I do notice that there are many kids who never want to be in school, but they always want to be at 601 Tully. Neighborhood kids frequently drop in and sit in on my college classes. They gravitate towards what is happening at 601 Tully as a different kind of school, of education. It is adult and serious. Or rather, adults who are taking them seriously.

RICK LOWE: When you were reading that, I was thinking about something else that is the dark side of that beautiful, idealistic way of thinking about education. The dark side I remember as kind of being—a light went off for me on the dark side of it when I was reading, I think, Aristotle's Politics. He was talking about the role of the state. One of the roles of the state was to determine who gets to learn what and how much of it. Looking at the state as governing education and educational offering. I think about this all the time. There is something about the way educational institutions apply education that is almost as if they are intentionally not make it interesting for certain people. So it alienates them from the process of education or the possibility of education. Even when you talk about it in terms of engaging on a community level, I think that is one of the ways that decisions about who gets to learn what happens. If you are educating in ways that you guys do at 601 in a neighborhood where kids have a chance to see and be a part of that neighborhood and learning in the context of the neighborhood, it is much more interesting and there are many more possibilities for them. But, generally, most educational institutions do not offer that kind of educational opportunity, where people get to learn within their community context. So dealing with any number of social service issues that happen around most university areas, the tools to deal with that—there are people that have tools to deal with that and they are dealing with them in different parts of the world all over. But they are not dealing with them in the context of the neighbors that are near them. To me, it's almost in fear that they will figure it out. If you educate them in their own neighborhood, they are going to know how to deal with some of these issues on their own. Why would we want them to know how to deal with these issues that they are dealing with because that's freedom? The education in that sense is freedom, and it is very powerful. Something thats still like—there is an institutional desire to not make education accessible to people—to their neighbors, to people that are in that context.

MARION WILSON: I think it also has to do with authority and, obviously, control.

RICK LOWE: Of what? Say that again?

MARION WILSON: Authority and control, which usually lie in the hands of—in this particular case it would lie in the hands of the teacher. I will just give one example, which in building 601 Tully—it was interesting because on the one hand, I felt as a professor completely vulnerable and not in control or not an authority figure, which I should be as a professor. But also, I was in control of the fact that I was giving up control in order to make the project evolve in a way that it needed to evolve. So, one example was—which again is a kind of a design thing—I arranged for the purchase of the building, and we knew we were going to redesign it, but we never decided until the second year what it would actually be. Which is very disconcerting to architects and city planners, zoning boards and construction managers. They used to say to me, "Marion, in four words, could you just tell us what the building is going to be?" But it wasn't ignorance—it was necessary. The building needed to evolve based on the way that it would be used in the partnerships that were developing. I mean, I knew to some extent what it might be. That it was educationally zoned, and artists would inhabit it, and I would move my college teaching there. But it needed to lay in this space of openness and ambiguity to see how it was going to be used, to see who walked in the front door; and then tease out the priorities. So, that's one way of giving up authority. I was teaching a class on designing this building. But what was it going to be? It sounds flakey, but in fact it was intentional and important.

And then there's this notion of collaboration. I know you have experienced this idea of collaboration and expertise. Universities and scholars are supposed to have expertise, right? I mean that is what they think they have. But we are in a neighborhood that I know nothing about and at very best I'm an uninvited guest, and that's the same with the students. I had no expertise about the neighborhood. So to immediately make a collaborative team where a high school student who grew up in the neighborhood is an expert in the same way that I might be an expert in conducting a focus group. You know what I mean? It's where education doesnt become a hierarchy, but rather it becomes a kind of sharing of information as opposed to just kind of one person pouring information into another.

RICK LOWE: I hear you. I think that I'm kind of saying the same thing. But I'm a little bit more cynical than you are. There is a real fear in this country of poor and working class folks becoming powerful and learning what that means. How do you take something like what you are doing at 601 Tully as just a symbolic gesture to say, "What I have is the goal to fix this house but not to tell you what it is. We are going to allow you to be in a process to figure out what it is yourself. So you then have the knowledge and information about how this happened."

Also, if you are speaking of institutional education as delivered by our schools, colleges, etc., I think you are more optimistic than I am. If you consider the black community historically, "education" has been a source of limitation rather than freedom. Carter G. Woodson wrote about this in his book The Mis-Education of the Negro (2005). Black people and communities managed to achieve what I believe was a higher level of freedom through scrappy freethinking and entrepreneurial spirits than we have as "educated" folks. As Woodson explains, schools and colleges were training black people to be educated slaves to someone else's creative entrepreneurialism. In other words, black people were being miseducated away from the creative, entrepreneurial practice that brought us out of slavery into viable economic and cultural communities. I think it was Mark Twain who said this in a humorous way: "I never let my schooling interfere with my education." So while I would agree that education is a practice of freedom, if we attached all meaning of education to institutional learning, it can turn out to be quite the opposite.

Work Cited

Aeschbacher, Peter, and Michael Rios. 2008. "Claiming Public Space: The Case for Proactive, Democratic Design." In Expanding Architecture: Design as Activism, edited by Bryan Bell and Katie Wakeford, 84–91. New York: Metropolis Books.

Bishop, Claire. 2012. Participatory Art and the 2012 Politics of Spectatorship. London: Verso.

Beuys, Josef. 1974. Quoted in Art into Society, Society into Art by Caroline Tisdall. London: ICA.

Lippard, Lucy R. 1997. The Lure of the Local: Senses of Place in a Multicultural Society. New York: The New Press.

Shaull, Richard. [1968] 2000. Foreword in Pedagogy of the Oppressed, by Paulo Freire. New York: Bloomsbury.

Woodson, Carter G. 2005. The Mis-Education of the Negro. New York: Dover.