Reading the career narratives of publicly engaged scholars in Imagining America's "Tenure Team Initiative on Public Scholarship" and contemplating the themes of this issue of Public provoked these authors—a doctoral candidate, an assistant professor, and an administrator at the same tier-one university—to think about their own journeys. These narratives of hybrid artists, designers, educators, and scholars might be beneficial to others in finding solidarity, identifying practices, and contemplating how to curate a career and navigate the siloed disciplines of academia.

Doctoral candidate Kate Collins gives the first account. Currently in the Department of Arts Administration, Education and Policy at Ohio State University, Kate's journey is one of personal discovery. She refers to herself as someone "in-between," and her career as a hybrid artist/educator/scholar. Kate has cultivated a career path that reflects her values of social justice, entrepreneurship, community building, and interdisciplinary collaboration. Her primary objectives as an educator are to work with youth and undergraduates in their formative years in order to understand the various roles of an artist, and to explore how artists can impact society and contribute to positive social change.

Susan Melsop, in the second narrative, describes three strands of her integrated career path: architectural pedagogy, a personal-spiritual journey, and the pursuit of a tenured academic position in design. She integrates teachings from Buddhism and practices of mindfulness into her scholarship and teaching, and explores relationships between design-build pedagogy and participatory place-making in an effort to advance socially engaged design and sustainable community development. Susan shares her experiences and concerns as an educator in an architecture school. In a tenure-track position, she finds opportunities to develop community design-build studios that engage urban youth in codesign and construction processes. She creatively expands design education beyond the campus and reimagines design processes as inclusive activities for social transformation.

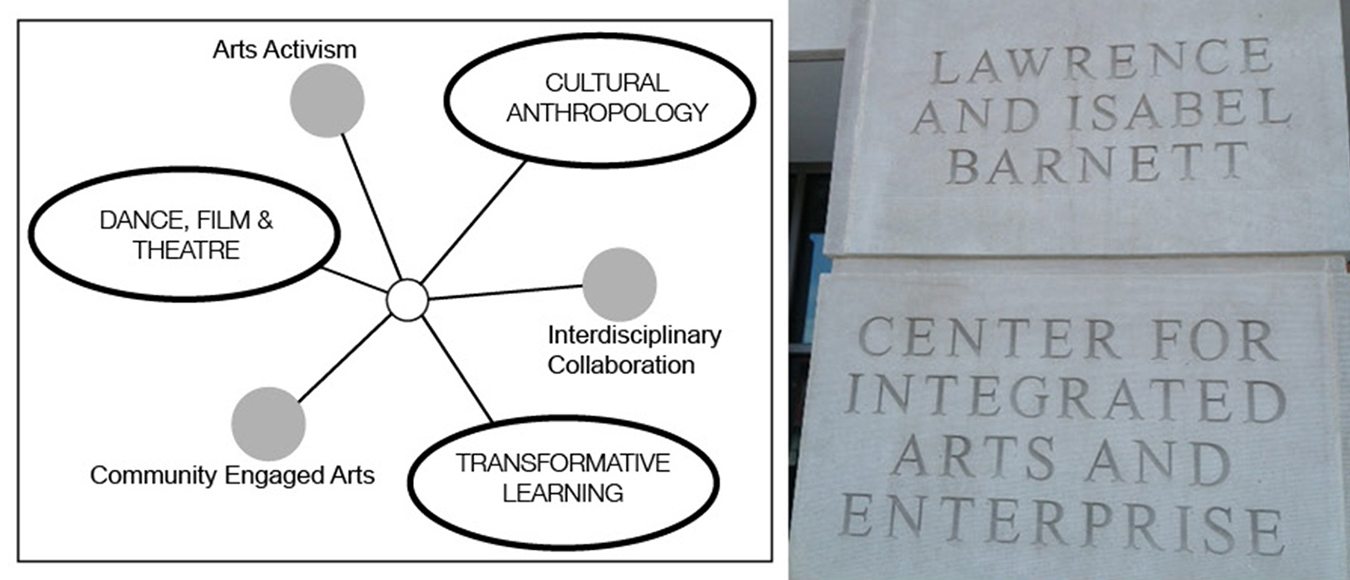

Third, Dr. Sonia BasSheva Mañjon, director of the Barnett Center for Integrated Arts and Enterprise, describes an evolving path from cultural and ancestral knowledge to engagement as artist, administrator, and anthropologist integrating interdisciplinarity and hybridity. Participation in arts and culture was cultivated in her household growing up. Language, food, and movement all shaped her being and sustained her career path in community arts, arts administration, and academe. Her building blocks were dance, business practices, and the ability to construct something out of nothing. Her comfort with interdisciplinarity led to her success in developing the Center for Art and Public Life, a community arts major, and sustained community partnerships. Her journey transitions from artist to scholar, administrator to vice president, and back to artist/scholar.

Hybridity: Embracing the Places In-Between

Kate: I am an artist/scholar/educator with an increasingly hybrid arts practice. I am committed to introducing other artists to the potentials of hybridity. As a university arts educator, a shift toward hybridity is crucial to provide student artists with a broader vision of how to create a meaningful life in the arts. In this model, art-making includes not only self-expression, but also community organizing and entrepreneurship, where artists facilitate communication and exchange, fostering public participation around challenging social issues. This outlook, which I have cultivated for close to twenty years, is in stark contrast to how I was trained as an artist.

Growing up, life was all about becoming the prized "triple threat"—dancer, singer, and actress. Throughout my undergraduate BFA acting training, I passionately aspired to Broadway and film. However, upon arriving in New York City to pursue a long-anticipated career as an actress, these passions quickly dissolved. I was disillusioned by the prospect of chasing after national commercials for years to achieve financial stability. I was disheartened by roles without pay that required nudity, and the constant superficial emphasis on my physique, my hair, my teeth, and my wardrobe. Stunned by the number of exceptionally talented 30 and 40 somethings, too many of whom were still struggling artists, I resolved to do something different. The problem was not knowing what other options existed for a livelihood as an artist. Sadly, the culture of my undergraduate program and amongst my peers was that anything that smacked of a "backup plan" was perceived as evidence that one was not a serious artist. This story is not unique to me, or to theater; many young artists face this same struggle. Like any proud, hard-core artist, I clung tightly to a myopic outlook . . . until for some reason, I didn't.

My career transition began with sitting on the floor of a Barnes & Noble pre-widespread Internet access, poring through books for ideas of other ways to put my artistic skills and talents to good use. I was at a loss. I considered drama and dance therapy, but was ultimately inspired by educational theatre. Despite little exposure to it, I gravitated to art-making that focused on social impact. After two years of employment in educational theatre, I began an MFA Theatre program. I continued my work as an independent community-engaged artist, a director of education for a regional theatre company, and an administrator and faculty at universities. In 2006, I became full-time faculty in theatre. Attending conferences such as Imagining America provided opportunities for me to converse with colleagues from across the nation in other arts and humanities disciplines. From these convenings, commiserating with equally frustrated colleagues, I realized that many US colleges and universities continue to offer students a narrow vision of the arts and artists in society. Institutional change has been slow for many arts departments. When arts faculties and tenure plans are entrenched in outdated values, students continue to replicate these outlooks and practices. Feeling boxed in and frustrated with reproducing old models, I decided to pursue a doctoral degree. This has enabled me to further study, imagine, and articulate a more expansive university arts education, which I believe is critical in today's society in order for artists to have more sustainable lives in the arts. Pursuing a doctoral degree in an arts education program rather than theatre also provides a much-needed critical distance from my original discipline, allowing me to actively and aggressively reevaluate my future as a university-based arts educator.

Currently, my studies involve delving into art historian Grant Kester's (2004) conception of the dialogical aesthetic, where discursive exchange becomes the medium of expression and process-oriented collaboration becomes the product. In response to Kester's queries about how artists prepare for ethical engagement in such work, I am compelled to introduce young artists to art-making that fosters intercultural and intergenerational collaborations and relational exchanges. These process-oriented practices invest in dialogue and empathy, and bridge building and border crossing between those who have not been able to come together to solve problems and address differences.

It is not my belief that all of my students should become community-engaged artists. But beliefs about what it means to be an artist form early, and all can benefit from a broader outlook. We cannot wait for students to attend graduate school to offer them critical learning opportunities and hands-on experience with engaged art-making; hence, my particular interest in collaborations between youth and undergraduate artists in their formative years. Practices of community-engaged arts offer pivotal occasions for challenging long-held notions of the aesthetic, opening up critical conversations about access, and pushing at the boundaries of the artists' role in society. Furthermore, these lessons provide essential opportunities for young artists to see that success in the arts can take many more shapes and forms than typically addressed. Sonia and Susan, who similarly prioritize dialogic engagement and systemic change through their practices with youth and undergraduates, validate these concerns and provide me with a small but critical network of support here at OSU.

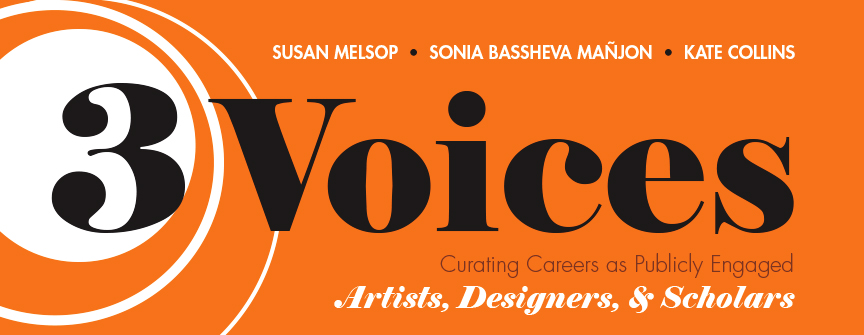

At present, I am finishing my doctorate; my mind is open to what comes next. Imagining America's Tenure Team Initiative report argues that to "encourage top-notch scholarship that contributes to the public good, we need to look hard at the culture of the academic workplace, including the places and spaces in which we do our best work today" (Ellison and Eatman 2008, iii). To do the work I care about most, I gravitate to the spaces in-between that allow me to act as a bridge builder, mediator, and facilitator. I feel most at home, most productive, between universities and the surrounding communities, faculty, and administration; between artistic disciplines, youth, and adults; and between the various socio-cultural identity groups. As I proceed with my search, I seek guidance and support from colleagues like Susan and Sonia, who have traversed similar paths and can help me navigate these waters, and I keep my eyes open for those spaces of possibility—those spaces in-between. (See Fig. 1.)

The Braiding of Lived Experience

Susan: Weaving together multiple strands of lived experiences is my modus operandi. While I do not separate my personal life well from my professional work and aspirations, my strengths lie in translation of these experiences into emotional intelligence, empathy for others, and questions of self. Living in São Paulo, Brazil for a few years as a child instilled in me the value of diversity and multiculturalism. Exposure to a culturally diverse metropolis with intense socioeconomic disparities was dramatic and traumatic. The socio-cultural sensitivities derived from these experiences have profoundly impacted my consciousness, personal growth, and professional development.

I am trained as an architect and educator, yet my deep interests reside in Eastern philosophies and cultural anthropology. These inform much of my teaching and research. I have taught undergraduate architecture studios and have had opportunities to develop graduate seminars that focus on sacred space, full-scale construction, and multicultural learning. Seminars on sacred spaces of Japan expand ways of learning and thinking about architecture. These courses were informed by my postgraduate studies in philosophical-religious traditions of Japan, Buddhist art and iconography, personal practices of mindfulness, and mind-body synchronicity. Most architecture pedagogy in the US is informed by traditions and cultures of Western civilization; philosophical traditions, belief systems, and built environments of other parts of the world are grossly overlooked. This misses an opportunity to expand our thinking and challenge our cultural perceptions and ways of being in this world.

The seminars on sacred spaces of Japan provided me with opportunities to unpack Cartesian conceptions of self and a patriarchal sense of individualism with students. The learning was transformative; the in-depth study of a culture outside Western civilization fueled our imaginations to think beyond what we had come to know as "true." Suzi Gablik reminds us of "the possibility of constellating a self beyond the egocentric one that has risen to power in the modern world" (a compelling notion raised by David Michael Levin), and urges that we as individuals reimagine our interdependence and interconnectedness as "radically related" (1991, 176, 178). As rich as these ideas are, they often remain abstract for students since they have little opportunity to enact practices of democracy within design processes or embody ontological questions of self through empathic design practices. My studies in Tibetan and Zen Buddhism and Yoga have influenced my interests in "whole person" learning, synchronizing mind, body, and spirit. Whole person learning is affective learning. That is, a transformative change occurs affecting one's emotional, mental, and psychophysical state. The essence of becoming is the cultivation of mindful awareness of one's relation to and place in the world.

Following many years teaching as an architecture adjunct, I moved into a tenure-track position, and from an architecture school to a design department. This move provided opportunities to expand my design-build pedagogy and transformative learning coursework. The department chairperson encouraged me to develop interdepartmental, interdisciplinary courses. Building on my relationship with a local nonprofit, I proposed an interdisciplinary service-learning course inspired by the design-build pedagogical model Samuel Mockbee developed for the Rural Studio at Auburn University. Mockbee was instrumental in orchestrating construction projects to serve residents of Hale County, Alabama, one of the poorest counties in the United States. With an emphasis on cultural exchange, I employed participatory design and codesign methods in order to engage urban youth in my design-build coursework. My interests lie in the investment of the creative capital of youth and in providing opportunities for design students to practice social equity through design processes. My studies in psychosocial development, multiculturalism, and collective place-making inform my teaching approach and research interest in socially engaged design practices. As the first of its kind in the department, the then chairperson enthusiastically endorsed the new course. It attracted students from across the campus interested in experiential learning and design-build opportunities with community members.

The social innovation methodologies of Theory U developed by Dr. Otto Scharmer and the convivial tools created by Dr. Elizabeth B.-N. Sanders have influenced the integration of my teaching, practice-based design research, and service (Boyer 1990). I published in the area of community-engaged pedagogy and social design. Two university awards for my service-learning teaching and community engagement gave me the impression that my trajectory toward promotion with tenure was on track—until it wasn't. When it came time for my review, questions arose about scholarship.

As an integrated, collaborative practice, my design-based research does not fit within conventional modes of disciplinary-based evaluation. While many colleagues recognize the value of my work, others are not familiar with engaged scholarship or how design processes can be employed for inclusivity and social change. National consortia such as the Engagement Scholarship Consortium and Imaging America are not on their radar. For many of my colleagues, design research has been driven by industry and commercialization, not humanitarian concerns. As a tenure-track candidate, it was my responsibility to articulate the necessity of this type of design pedagogy, demonstrate the value of advancing design tools for interdisciplinary and collaborative work, and assess the impact of my community engagement. Socially engaged design is an emergent field. As such, challenges exist in evaluating its practice and scholarship.

Making alliances across departments and providing examples of other scholars' community-engaged work demonstrate the seriousness of this work. Collaborations with Kate and Sonia provide me a small network of like-minded academics and a safe space to continue pursuing socially engaged design. Our contribution to the Imagining America 2013 conference indicates the expanding nature of interdisciplinarity and the growing fields of community arts and social practices. The adoption and adaptation of the visual tools we developed for seminar participants validates the usefulness of new communication tools to advance engagement practices.

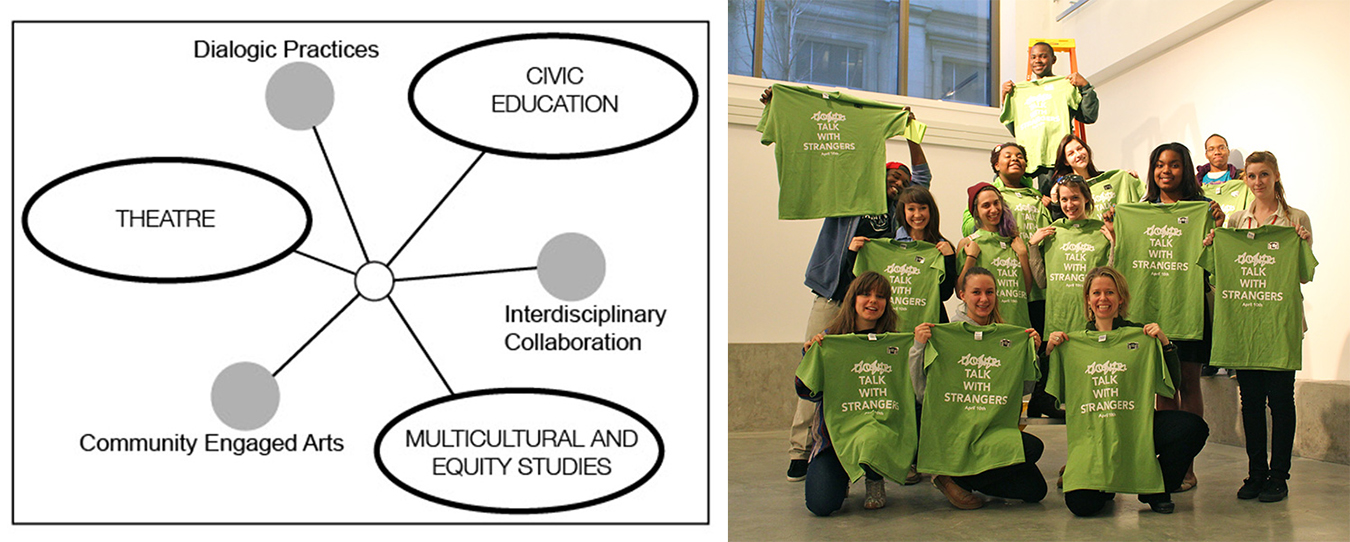

Like a braid, the strands of "lived experiences" of my professional, personal, and academic life are woven together to form a whole. (See Fig. 2.) This integrated approach provides me the wisdom, compassion, and resilience to carry on.

Evolving Ways of Being

Sonia: My world has always embodied hybrid and evolving ways of being. Growing up in a Dominican household, language was fluid—the exchange between Spanish and English forming a Spanglish dialect was constantly corrected by my abuela but encouraged by Mami. Dancing merengue, salsa, and bachata at home, while studying ballet and modern dance at school, filled my soul and trained my body for the flexibility and coordination I would need while interacting with different people on multiple projects. My world became a collaborative evolution, open to exchange and multiple ways of looking, and most importantly regarding my place within it.

This all shaped my development as an artist. As an undergraduate, I developed an Ethnic Art Festival at UC Berkeley in order to explore and explicate the many voices and cultural identities that would become my career focus. I majored in business and dance. I finished my undergraduate degree at UCLA in World Arts and Cultures, which provided everything I needed to complete my development: theatre, dance, folklore/mythology, ethnomusicology, visual cultures, arts activism, and critical ethnographies.

Graduate school gave me a way to articulate what I was feeling, experiencing, and working toward. Studying cultural anthropology fueled my need to work in community that later became the basis for a PhD in transformative learning. Like Susan and Kate, I adopted an integrated approach to learning and teaching through community-engaged pedagogy and campus-community collaborations. It was the perfect combination to my artistic work in dance, theatre, video, and photography and my scholarship in participatory-action research. I juxtaposed art with scholarship.

I became director of the Center for Art and Public Life at California College of the Arts (CCA), which challenged both the institution and the community in defining what enables transformative change and how education integrates with art and community in producing and sustaining that change. The culture of CCA was one of rediscovery, creating a place and space in which to approach new ideas in academe involving civic engagement, community partnerships, and new academic programming. A new president and the approaching 100th anniversary of the College made for fertile ground in which to explore the interdisciplinarity of the artist/scholar connecting with community in solving problems, and engaging students in that process. This process didn't happen without consequences: questions being raised in the tenure and promotion process that did not value engaged scholarship; junior faculty having to abandon this work in early career choices; and the ushering in of the new Center for Art and Public Life and the new community arts major that had civic engagement and community partnerships as primary foci. Faculty were apprehensive about committing to involvement in the Center, even if they believed in the mission, until the impact on career trajectory and time commitment could be further explored. Developing outside university partnerships and collaborations (community, corporate, foundations, and government) helped guide the college to a level of acceptance and ultimately participation across departments and disciplines.

As I brought the Center into national consortia of universities and colleges committed to sustained educational practices through art and community partnerships, the dialogue that Imagining America was beginning on tenure and promotion and defining public scholarship was producing language that proved useful in our internal processes. Working with such partners as Maryland Institute College of Art, Columbia College Chicago, Xavier University of Louisiana, and others, we hosted a series of national convenings to initiate and support this work and create common language that could contribute to the tenure process, curriculum development, pedagogy, and community-campus partnerships. We sought to develop and implement a peer review process to critically examine curriculum, pedagogy, practice, theory, and projects. The Community Arts Journal, an online publication of the Maryland Institute College of Art, helped to ground us in this work and create scholarship. First-year submissions focused on critical pedagogy, campus-community partnerships, values and beliefs in community practices, and aesthetic forms. National convenings and publications contributed to an understanding of how to do this work in the academy and received acknowledgement that contributed to the tenure process and curriculum development.

As I participated in the dialogue around cultural activism and art production, the overarching objective was to support community arts, not only as a field of study through the development of the first BFA in community arts in the fall of 2006, but also as a call to activism through community engagement and campus-community partnerships. As I examined and critiqued the service-learning pedagogy used in the academy and questioned the benefits and reciprocity to, for, and with community, many questions and debates occurred. In our collaborations with community, were we cognizant of equitable distribution of funds and resources? Did we recognize the need for capacity building between the academy and the community in planning and implementing community-campus partnerships? How did we ensure the long-term commitment of the academy in sustaining these partnerships? Or did the academy only participate in community partnerships for the semester that the classes were offered or until funding was depleted? These questions would continue to be debated throughout my tenure as director of the Center.

Coming full circle, I am back in an academic position and program at Ohio State University that supports my scholarship and teaching, and once again building a center that will incorporate the campus-community paradigm that I believe is at the nexus of civic engagement, scholarship, and curriculum development. Reconnecting with colleagues from my earlier CCA days, such as Kate, and new colleagues such as Susan, has led to new collaborations. The three of us presented a seminar, Designs, Structures and Spaces: A Dialogue Integrating Undergraduate Student Engagement for the 2013 Imagining American National Conference. Expanding on the ideas presented in Full Participation: Building the Architecture for Diversity and Community Engagement in Higher Education (Sturm et al. 2011), we codeveloped concept maps to help the user identify support systems and relationship builders to support engaged work either as a faculty member or as a student. Our collegiate relationship also helps to sustain our work as engaged scholars, artists, and designers.

The lesson I have learned throughout my professional life is that the process may be challenging, but the outcome is worth the journey. By not allowing myself to be isolated by one art form, one type of position, or one institution or organization, I've evolved into an interdisciplinary way of being. The benefit is the ability to adapt to change and survive any trial. These multiple experiences have given me strength to persevere in any environment, knowledge to share with my students, and support to offer my colleagues on similar journeys. (See Fig. 3.)

Reflections

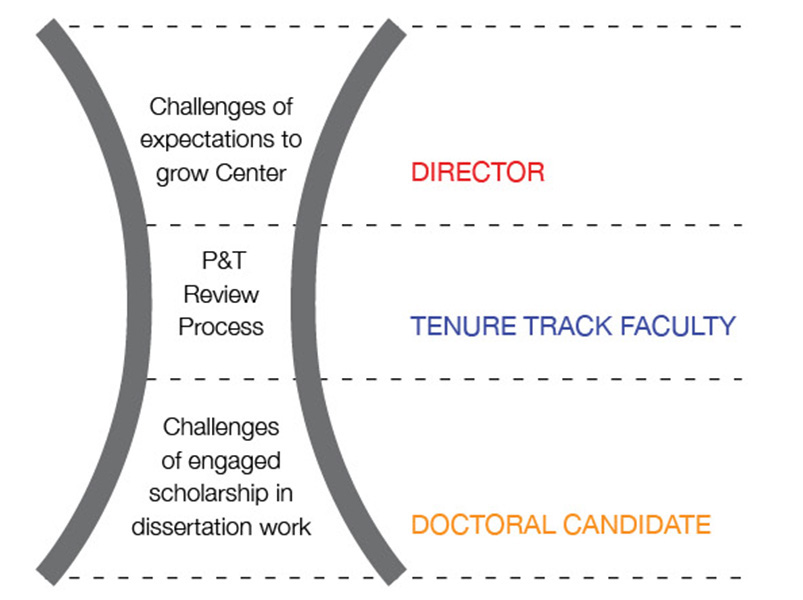

Although our backgrounds and current positions are different, shared values, principles, and practices bring us together. A director has vast opportunities and high expectations to expand engagement and create entrepreneurship in the arts. A tenure-track faculty member faces departmental pressures to validate the scholarship of socially engaged practices and demonstrate the advancement of the discipline through engagement. A doctoral candidate has flexibility in shaping a study that reflects one's passions, as well as challenges that come with expectations of focusing on theoretical inquiries over creative practice. The abstract image of an hourglass provides a visual of the research pressures felt at the rank of a tenure candidate, while the top and bottom of the hourglass indicate the expectations and expansive opportunities at the rank of an administrator and doctoral candidate. (See Fig. 4.)

The support we provide one another becomes all the more vital when we consider not only how much stamina community-engaged practices require, but also the varying degrees of validation these types of practices demand within our departments, colleges, and universities. We are all hybrids. We are all ever evolving. We are all invested in integrated practices. Helping each other find the will and inspiration to continue honoring these qualities within ourselves and to keep pushing against the boundaries of the traditional frameworks and structures that we exist within has been the vital role we play for one another.

Work Cited

Boyer, Ernest L. 1990. Scholarship Reconsidered: Priorities of the Professoriate. Princeton, NJ: Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching.

Ellison, Julie and Timothy K. Eatman. 2008. Scholarship in Public: Knowledge Creation and Tenure Policy in the Engaged University. Syracuse, NY: Imagining America.

Gablik, Suzi. 1991. The Reenchantment of Art. New York: Thames & Hudson.

Kester, Grant H. 2004. Conversation Pieces: Community and Communication in Modern Art. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Strum, Susan, Timothy Eatman, John Saltmarsh, and Adam Bush. 2011. Full Participation: Building the Architecture for Diversity and Community Engagement in Higher Education. Syracuse, NY: Imagining America.