Introduction

In Imagining America's call for submissions for this issue of Public, titled "Hybrid, Evolving, and Integrative Career Paths," the editors posed several intriguing questions:

What alternatives to siloed, static, or linear job trajectories do public scholars, designers, and artists generate? How are skills associated with one discipline applied to something else, in some cases by moving between an academic position and on-the-ground engagement? (2014)What I hope to contribute here is some reflection on how we can claim our work as interdisciplinary in the broadest sense, not just crossing the boundaries of academic disciplines such as history and literature, but drawing from entirely different epistemologies. Even though our work is often viewed more narrowly because of professional position or institutional home, we can conceive our work in a much broader sense. Much of my career has involved work that I call hybrid, in my case the translation between expert models of knowledge, which are often embodied in institutions of higher education, and experience models of knowledge, which are often embodied in community-based organizations or networks. This hybrid work of translation has changed forms depending on my professional positions and institutional homes over the years, but remains a theme in my life's work. I recognize that it is the space between these seemingly oppositional models of knowledge that I find most challenging and fascinating.

Contrary to claims that humanities disciplines have little practical application, I demonstrate here concrete ways in which the study of nineteenth-century American literature yields a model for nonconfrontational work between partners in which privilege and need have created a power imbalance.1 Having read in detail about the historical conditions of African Americans enslaved in the United States, I can more fully appreciate why a white face might often be received with distrust or even anger in an African American community today. I take it less personally that a black person looking at me might only see my white skin and make any manner of assumptions about me. Having studied narratives that uncover the justification of cruelty in the mask of benevolence, I am more suspicious of claims made by outsiders that they have come to help a particular community. Examining the ingenious ways in which African Americans have resisted white hegemony over the years highlights for me the resilience of a long-suffering people. Learning that even African Americans sometimes owned slaves, and that even slaveholders sometimes helped other slaveholders' fugitive slaves escape, complicated my understanding of human motivation. These experiences make me more able to recognize connections between race and benevolence among groups involved in humanitarian efforts today.

The early part of my career—nearly two decades of work in the burgeoning late twentieth-century community-based learning (CBL) movement within higher education—eventually led me to pursue a doctorate in nineteenth-century African American literature.2 The term community-based learning is sometimes used interchangeably with service-learning and community engagement. Community-based learning has been defined in various ways, but the definition used by the National Service Learning Clearinghouse, as quoted and commented on by the Center for Teaching at Vanderbilt University, provides a quick, useful, and concise definition:

Community engagement pedagogies, often called service learning, are ones that combine learning goals and community service in ways that can enhance both student growth and the common good. In the words of the National Service Learning Clearinghouse, it is a teaching and learning strategy that integrates meaningful community service with instruction and reflection to enrich the learning experience, teach civic responsibility, and strengthen communities. (Center for Teaching 2014a; Center for Teaching 2014b; Great Schools Partnership 2014)

The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching defines community engagement in this way:

Community engagement describes collaboration between institutions of higher education and their larger communities (local, regional/state, national, global) for the mutually beneficial exchange of knowledge and resources in a context of partnership and reciprocity. The purpose of community engagement is the partnership of college and university knowledge and resources with those of the public and private sectors to enrich scholarship, research, and creative activity; enhance curriculum, teaching and learning; prepare educated, engaged citizens; strengthen democratic values and civic responsibility; address critical societal issues; and contribute to the public good. (Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching 2014)

I, too, sometimes use these terms interchangeably. More important than what term is used, however, is that within the context of one's work, the partners involved have a negotiated understanding of what they mean by the term they use to describe their joint community project.

Facilitating community-based learning over the years provided me with a new framework for relating my stories to those of others and for understanding my own positionality. Sociologist Gerard Delanty's observation that

Citizenship takes place in communicative situations arising out of quite ordinary life experiences. . . . [A]n essential dimension of the experience of citizenship is the way in which individual life stories are connected with wider cultural discourses (2002, 65)resonates particularly well for me.

Working in African American communities showed me my white racial identity from another perspective. The dynamic of power in benevolent relationships—especially when race is involved—is highly nuanced and complex, as will become clearer later in this article. I began to interrogate my own position in relation to those in need and to African American groups in particular. I questioned my motivation to engage in this kind of community work and grappled with my own feelings about the imbalance of power inherent in benevolent relationships. The more I learned, the more I realized what I didn't know. I came to see how my own cultural identity limited what kinds of perspectives I had been exposed to, and that it took real effort to seek out alternative perspectives. I began to view culture as a powerful influence when working toward social change. Understanding an individual's or a group's culture creates a spirit of openness and a foundation for building trust.

Reflections on the Early Part of My Career

My community-based learning work engaged me in ongoing discussions about what it means to do good for others and what effects helping others can have on the involved parties. Because my community-based learning work took place in and around the racially mixed environment of Washington, DC, this period in my professional life sharply focused my attention on diversity and inclusion. Working primarily with majority-white institutions of higher education, I was often in the position of sending white students out to serve black communities (what I term racialized benevolence).3 With others' guidance, I soon began to appreciate the problematic nature of such an arrangement.

The intersection of race and benevolence became even more complicated. At one point I was the sole white person in a community service program—the white program coordinator of a mentoring program, initiated by black undergraduate students, which worked with black middle school students. The mentors graciously taught me how to navigate the social relations within their group. Then there came a day when a blond-haired, blue-eyed student entered my office to express her interest in becoming a mentor in the program. I found myself awkwardly explaining that while white students were welcome to serve as mentors in the program (in fact, we had one white student in a group of about 15 mentors at the time), by design the majority of mentors were black. She politely explained to me that although I assumed she was white, she came from a mixed racial heritage. I had to examine my assumptions about race as a fixed identity.

On another occasion, one of our male mentor leaders apprised me of his inability to hail a taxicab from the front gates of our prestigious university. He challenged me to reflect on business owners' perceptions of young black males, even those who might be attending a highly selective university. In the course of my work, I learned that there was a Black National Anthem and how to sing it. I had been ignorant of a significant symbol of cultural identity for African Americans because, as an outsider, I had few, if any, opportunities to encounter it. In my community work, however, such opportunities were increasing dramatically. As a white person, I had been socialized to understand race as a fixed identity. In the context of the community-university partnerships I was involved in, I was experiencing a wider range of racial identities and beginning to view them as less fixed, more fluid. Racial identity was much more than skin color and was not necessarily a fixed identity because it could change according to context. I started thinking more carefully about the cultural work necessary for social change. Broadly conceived, cultural work signifies the ways we make meaning of our daily lives, deepen our understandings of diversity, and free ourselves from bondage in our own thinking. In my situation, this meant understanding how the legacy of historical events and figures shape the present, seeking out multiple perspectives about issues of concern in our communities, and documenting the stories of different cultural groups.

How Experience Led to a Research Topic

All of these moments of racial identity awareness served as background when I chose my graduate courses and research topic for my dissertation. I was drawn to what has been called benevolence literature, the literature of philanthropy, poorhouse stories, and the like. The depiction of acts of benevolence—the voluntary provision of care or generosity toward someone in need—was a staple of the sentimental literature that was popular in the United States and Britain in the nineteenth century. Sentimental narratives sought to engage readers' emotions by depicting scenes of distress and tenderness.

Even in the nineteenth century, benevolence was a contested term, evoking ideas and values such as charity, humanity, good intentions, and goodwill, but one that activists across the political spectrum engaged . . . and argued over, at times vehemently (Ryan 2003, 9–10). Benevolence was a widely used term, but there was little consensus over what it meant or to what projects it could be applied. For some, it meant wishing others well; for others, it signified positive actions taken on someone's behalf. Some groups believed benevolence consisted merely of almsgiving; others viewed it as a means of alleviating, but not eliminating, poverty. Still others used it to describe efforts that would reform broader social structures.

One common but naïve view of benevolent action is that it consists of the more privileged giving to the less privileged, with all the benefit flowing from the presumably altruistic giver to the presumably grateful recipient. Yet the community-based learning movement has turned a critical eye to the inevitable power dynamics among benefactors and recipients. Some researchers in the field have questioned if such good works have done harm to communities being served. For example, Chris Koliba asks, Does service-learning contribute to the privatizing or downsizing of citizenship practices . . . or can service-learning be understood and practiced as a vital antidote to this troubling trend? (2004, 57) Others have argued that benevolence can actually solidify the inherent social inequality between benefactor and recipient and often serves only as a marker of difference, whether social, racial, or economic.

One of the first things I noticed about the literature I was studying—benevolence texts—was that they paid close attention to the social, political, and historical context in which they were produced. They were firmly grounded. The second thing I noticed was that they often involved different kinds of reversals, some of which were ways of turning situations of powerlessness into situations of agency, both for individuals and for marginalized social groups. I decided to build upon earlier literary critics' observations that these narratives not only evoked sympathy for the downtrodden but also sometimes masked power differentials in the social relations of the purveyors and the recipients of benevolence.

Among these benevolence texts, some reversals of subject positions involved white benefactors and white recipients. For example, Louisa May Alcott's novel, Work (1873), depicts a white woman, Rachel, who was a former recipient of charity going on to become a benefactor to other young white women. Christie befriends a fallen woman named Rachel. Much later in the novel Christie suffers her own crisis and considers suicide, but is rescued by Rachel. Other texts depict a benefactor eventually coming to need the very services she herself had been providing to others, such as a female nurse to Union soldiers during the Civil War becoming ill and being nursed by the more ambulatory of the recovering men, as in Alcott's Hospital Sketches (1863). Such reversals posit a kind of equality among the benefactors and recipients, especially because the benevolence is reciprocated.

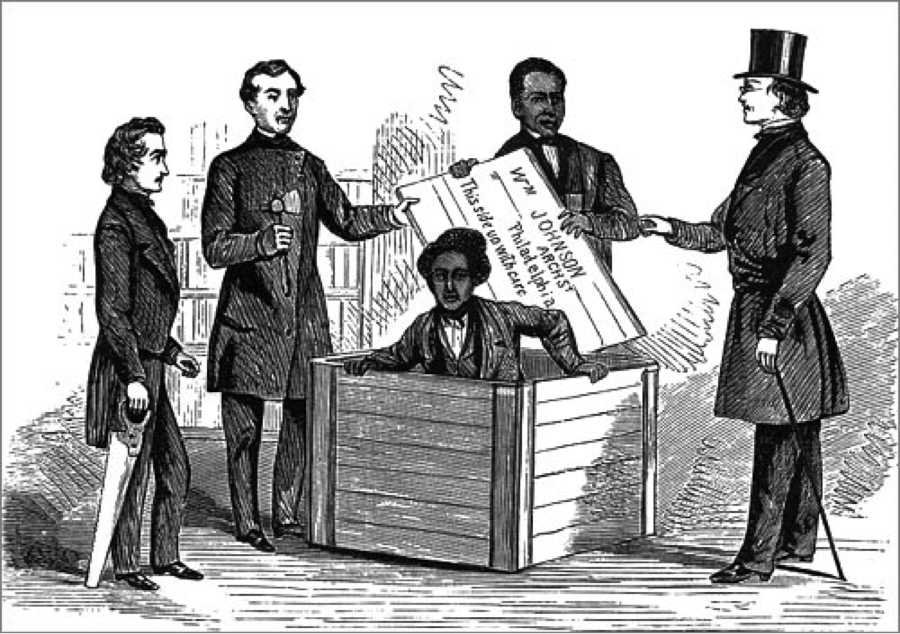

Reversals in other benevolence texts foreground race. Readers of the Narrative of the Life of Henry Box Brown, published in 1851, know how Henry gained his freedom. Assisted by friends, he literally shipped himself in a large box to the address of a Quaker home in Philadelphia.4 This man, enslaved because of his race and considered merely property or a commodity by slave owners, took the degrading identity with which he had been labeled, and literally used it to transform that identity. He willingly turned himself into a commodity, a package that could be shipped, in order to gain freedom and humanity, leaving his previous status as property behind. At his destination, abolitionists opened the box and welcomed him into their midst.

In Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom by William and Ellen Craft, published in 1860, an enslaved husband and wife disguised themselves as master and slave, traveling in plain sight from slavery in Georgia to freedom in Philadelphia. The light-skinned Ellen took on the demeanor of the master, mimicking him all too accurately, and William acted the part of the slave. Here, reversals of expectations were at play. Who would expect an enslaved individual to dare pass as a white master and perform the role so well that no one realizes it? Who would expect a slave to remain in public view, playing the deferential servant all the while, on the way to freedom? The Crafts were not dependent on white benevolence; they mostly accomplished their escape by their own wits. Once in Philadelphia, the Underground Railroad network assisted them.

William Wells Brown's account of his own escape from slavery, which he published at the beginning of his novel, Clotel, relates how Brown cleverly convinced his master's sons to teach him the alphabet (Brown 2000, 216). Although it was illegal to teach slaves to read, Brown circumvented this law. He regularly supplied the boys with barley sugar, a favorite type of candy. They served as his daily tutors for three weeks, by which time he had learned the basics and could teach himself. Here the roles of benefactor and recipient are blurred. Brown shows kindness to the boys by giving them candy. But his kindness has an ulterior motive; it induces them unwittingly to give him the gift of literacy. They don't understand the import of their gift, but Brown does. Under the guise of a benevolent scene, there's something else happening. Brown's kindness to the boys is actually street smarts.

There were many options I could have pursued in my research. The numerous examples of reversals of traditional positions in the benefactor-recipient relationship were fascinating, but too varied to categorize. Not only were there reversals in the literary texts, but often in the lives of the authors as well. For example, Harriet Jacobs, much later in life, learns that some of her former master's relatives have fallen on hard times. Knowing that they live nearby, she prepares a generous dinner for them and delivers it personally. I was quite surprised at this compassionate response, when deep resentment was easily justified. Nonetheless, Jacobs serves as a benefactor to her former master's family (Yellin 2004, 246). I finally decided to focus my research on scenes in which African American authors demonstrated their agency and equality as citizens by reversing black positionality within the traditional benefactor-recipient dynamic.

Benevolent acts are not simply moral or virtuous but also socially structured, influencing what individuals within that society choose to do and how those acts might be received. Narratives of benevolence often mask power relations of subjection and coercion (Hossfeld 2005, 11). Ironically, many slaveholders justified slavery by saying they were benevolent masters, men who gave heathen Africans Christianity, and civilized, fed, and clothed them. I sought to understand what happens when nineteenth-century African Americans (often formerly considered commodities themselves) act as benefactors rather than recipients. In the same way that the nineteenth-century American discourse of benevolence names and produces identities and power relations among rich and poor, white and black, slaveholder and enslaved, benefactors and recipients, the African American authors whose texts I examined subvert the identities of white benefactors and black recipients by reversing their roles. My four chosen texts attempt to reframe expectations about black-white benefactor-recipient relationships and imagine possible futures that overturn the racialized benevolence dynamics that the authors saw operating in their own worlds. The authors of these texts reenvision and rescript the racialized roles that are often played out in acts of benevolence. While certain nineteenth-century ideologies promoted the idea of the grateful slave or the enslaved as happy and contented, these four authors use role reversals to show how oppressed groups subvert this mythology of benevolence.

This deep interest in questions of power in benevolent relationships led me to a then-new area within literary criticism that was interrogating these issues within mostly nineteenth-century sentimental literature. I soon realized, however, that the authors of those critical works had studied primarily texts written by white authors, almost all of them women, that depicted the benevolence of white, mostly middle-class benefactors—again, almost all of them female—toward those in need. Given the social and historical realities of that period, African Americans constituted a major class of those on the receiving end of these acts of benevolence.

This recognition eventually led me to wonder about how the power relationships implicit in benevolence might operate when the subject positions were reversed—when the benefactor was black and the recipient was white. Thus began my reading of more than sixty narratives written by eighteenth- and nineteenth-century American authors.5 Perhaps not surprisingly, given the precarious position of most African Americans as they were just beginning to emerge from bondage, few such depictions appeared in written narrative, whether because they were rare or beyond the imagination of most Americans writing at the time. Even when I narrowed my search to texts written by African Americans,6 I could find only four narratives that depicted black benevolence toward white recipients. These four narratives, though tiny in number, address significant issues and suggest a larger world of black persons acting with benevolence toward white persons. I had found a vein of literature so rich that I would continue to explore it for several years.

Four African American Narratives and the Reversals They Contain

The first of these texts, Absalom Jones and Richard Allen's A Narratives of the Proceedings of the Black People (1794), is a historical account of the 1792–1793 yellow fever epidemic in Philadelphia, written by two leaders of that city's free black community. The next two texts, written mid-nineteenth-century, are memoirs that depict the authors' journeys from slavery to freedom: Harriet Jacobs's Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861) and Elizabeth Keckley's Behind the Scenes (1868). (After achieving freedom, Keckley worked in the White House as Mrs. Lincoln's personal seamstress.) The fourth text, Charles Chesnutt's The Marrow of Tradition (1901), is a novel based on the post-Reconstruction Wilmington, North Carolina race riot of 1898. These four works, which roughly span the nineteenth century, cover three major events or crises in the history of African Americans as citizens: disagreement over the status of African Americans surrounding the adoption of the American Constitution, the turbulent national debate accompanying the Fugitive Slave Act and Emancipation, and the imposition of Jim Crow laws following Reconstruction. These four narratives all respond to and challenge the dominant literary and political narratives and discourses of their time, thereby also functioning as counter-narratives to previously studied nineteenth-century American benevolence texts that often focused on white-to-white or white-to-black benevolence. Individually and collectively, these four texts destabilize the status quo, display black agency, declare African American readiness for full citizenship, and press us to reshape the dominant American narrative regarding benevolence.

These texts taught me about some extraordinary, little-known instances of black benevolence toward white recipients (among both historical figures and literary characters) and introduced me to black commentary on white benevolence. For example, Absalom Jones and Richard Allen organized the black community to nurse the sick and bury the dead during the several-months-long epidemic of yellow fever in Philadelphia in 1793. (However inaccurate, at the time it was believed that people of African descent could not contract yellow fever. Richard Allen did come down with yellow fever, and was hospitalized for several weeks.) A white publisher praised Jones and Allen for their services, but insinuated that some of the other black nurses pilfered from white homes. That compelled Jones and Allen to write a response defending the work of the black nurses.

In another case of black-to-white benevolence, Harriet Jacobs speaks of Miss Fanny, a sympathetic white woman who asks how she can help when Jacobs is punished by her master:

She condoled me in her own peculiar way; saying she wished that I and all my grandmother's family were at rest in our graves, for not until then should she feel any peace about us. The good old soul did not dream that I was planning to bestow peace on her, with regard to myself and my children; not by death, but by securing our freedom. (Yellin 2000, 89)

This statement signals a failure of sympathy, Miss Fanny's resignation to the belief that the only escape from slavery was death, not integration into society. This belief prevailed even among sympathetic white friends. Jacobs rejects Miss Fanny's pity and plans to enact her own escape plan, through which she will bestow peace on Miss Fanny, a metaphorical act of black-to-white benevolence.

In the third text, Elizabeth Keckley explains how she supported her owner's family of 17 people for over two years with her seamstress skills, when their fortunes declined. Keckley's motivation was not strictly benevolence, but rather a strategy to protect her aged mother from being sold away (1868, 44). As a final example, in Charles Chesnutt's novel, a black doctor, Dr. Miller, decides whether or not to save the child of the town's leading white supremacist. This white man had earlier rejected Miller's services as a physician on account of color, and had fomented a race riot in which the doctor's son was accidentally but mortally injured (1901, 320).

In addition to portraying black benevolence to white persons, these four texts also offer critical commentary on white benevolence. In defending the black nurses, Jones and Allen state they can "assure the public that we have seen more humanity, more responsibility from the poor blacks, than from the poor whites" (10) They tell of a poor black man who gave a dying man a drink of water after several white people had passed by without attempting to help. Indeed, they state, "Many of the white people, that ought to be patterns for us to follow after, have acted in a manner that would make humanity shudder" (19). Beyond the economic support Keckley gives to her owner's family and the compassion she shows to the bereaved Mrs. Lincoln, she also depicts herself in the role of caring benefactor more commonly filled by white middle-class women in the sentimental literature of the time. Keckley not only organizes volunteers to provide charity to soldiers and the formerly enslaved, but she persuades Mrs. Lincoln to assist her, thus instructing the First Lady on her proper role as a woman. (1868, 114)

In the Chesnutt novel, Dr. Miller's black wife, Janet, confronts her white half-sister, Olivia, who has not acknowledged their kinship. Olivia finally recognizes Janet as her lawful sister and offers her the inheritance that she rightly deserves. Janet rejects this supposed benevolence, because "it had come . . . in a storm of blood and tears; not . . . from an open heart, but extorted from a reluctant conscience" (328). Infuriated at Olivia's offer, Janet declares, "My mother died of want, and I was brought up by the hand of charity. Now, . . . you offer me back the money which you . . . have robbed me of!" (328)

Of my four selected texts, only Jacobs's text explicitly addresses benevolence between slave owners and the enslaved, as well as the sexual exploitation of enslaved women by their owners. For example, Jacobs refutes the pro-slavery argument that enslaving Africans gave them the benefit of Christianity. She condemns the hypocrisy of Christians who "send the Bible to heathen abroad, and neglect the heathen at home. I am glad that missionaries go out to the dark corners of the earth; but I ask them not to overlook the dark corners at home. Talk to American slaveholders as you talk to savages in Africa. Tell them it is wrong to traffic in men" (Yellin 2000, 73). Jacobs inverts the image of the "heathen abroad" to signify the "heathen at home," the slaveholders who buy and sell human beings as property. In another instance, Jacobs reinterprets white persons' "gifts" to the enslaved, demonstrating that even sincere gifts can carry personally painful social messages. Jacobs relates how, when her daughter is christened, her father's old mistress "clasped a gold chain around my baby's neck. I thanked her for this kindness; but I did not like the emblem. I wanted no chain to be fastened on my daughter, not even if its links were of gold" (Yellin 2000, 79). The mistress's presumably good intentions only remind Jacobs of the constant threat of sexual exploitation that slavery will pose for her daughter as she grows up.

What Students Can Learn from Benevolence Texts

Knowing the social, political, and historical context of both American racism and American benevolence can help us understand how they developed, what conditions their existence, and what often connects them. Although I dutifully took an Introduction to Sociology course as an undergraduate, and learned that race was socially constructed, it was not until graduate school that I more fully grasped how the social construction of race changes from one place to another and one time period to another. Similarly, models of benevolence, including models of racialized benevolence, are also socially constructed and historically grounded rather than unconditionally virtuous because, for example, white benevolence to blacks has been shown to frequently involve the social control of blacks. In contrast, black benevolence to whites frequently serves as a form of resistance. It should not be surprising that racism and benevolence are connected today, were intertwined in the nineteenth century, and might have been so since the European settlement of what is now the American nation.

Benevolence remains a prominent theme in the American psyche today. Racialized benevolence, particularly benevolence from white benefactors to black recipients, often follows close behind. Writing amid a flurry of white American celebrity activists turning their attention to Africa at the beginning of the twenty-first century, adopting black babies and raising funds for the fight against AIDS, journalist Andrew Rice observed: "Indeed, the word 'Africa' has become a brand, synonymous with misery and moral obligation"(Rice 2006). These celebrities apparently are not adopting black babies from Baltimore or Detroit or, for that matter, white babies from Portland or Minneapolis, at the same rate that they are adopting black babies from Africa. Rice complements what literary scholar Susan Ryan asserted about the nineteenth century when she stated, "the categories of blackness . . . (or, at times, a generic 'foreignness') came to signify, for many whites, need itself"(1).7 American benevolence has evolved as a set of practices embedded in a racialized society since the nation's colonization by white Europeans.

Much of my professional life I have explored how students can be, in literary scholar John Ernest's words, "active readers of history"(2004, 8–10) and share historian James Sidbury's concern with the relation of discourse to action (2007). I expect my work to advance students' understanding of the connection between narrative and ideology, between the stories Americans tell themselves and the beliefs and behaviors that those stories justify. My hope is that students who might ordinarily dismiss the nineteenth-century texts I have examined here as melodramatic and distant from today's concerns, engage with texts like these and see how they complicate the intersection of race and benevolence. For twenty-first-century students, discussing race in the context of the nineteenth century might seem less threatening than tackling current racial issues. Once they have been exposed to new points of view about race and benevolence in American history and literature, perhaps students will become more able to engage in civil dialogue about race relations and benevolence today. It is easier to recognize racialized benevolence in the present day when you have seen it in the past. We can point out the operation of power dynamics in benevolent relationships in the nineteenth century more easily because we have some distance from that historical time and cultural milieu. Because we are immersed in our own cultural milieu, it is harder to identify the power dynamics in benevolent relationships today, unless we have some other point of reference.

Texts such as the four I have addressed here can help students make meaning of these new forms of ancient human problems. In my Politics of Giving course, students read excerpts from the four African American-authored texts I selected, and then we discussed current newspaper articles such as "How Can We Help the World's Poor?" by Nicholas Kristof of the New York Times (2009) and "Beyond Me; I Wanted to Help. But It's Not That Simple" by Michael Dobbs of the Washington Post (2005). Kristof's article discusses humanitarians' deeply divided positions on the subject of foreign aid to poor people in developing countries. Dobbs' article addresses the complications of giving aid in the wake of the tsunami that hit Sri Lanka in 2004. When students put these texts in conversation with one another, they can see patterns of racialized benevolence that would have been much harder to identify in one isolated article. Used along with current humanitarian discourse, the four African American-authored texts I have discussed can stimulate students' imaginations and prod them to more fully understand the dynamics of race and benevolence. It can also lead them to interrogate their own positionality in the benevolence dynamic. As books written for a social purpose, that are both literary and historical, the authors of these four texts pay close attention to the social conditions of black people. They examine and intervene in events hostile to African Americans because of their concern with the relation of discourse to action. They encourage readers to become critical readers of history, too, because historical understanding can lead to and, indeed, sometimes compel, moral action.

Conclusion

Learning how benevolent acts in nineteenth-century literature are not simply moral or virtuous but also socially structured, can give students tools for uncovering how such acts that they witness or in which they participate are socially structured today. This is an example of the humanities, which are so often deemed impractical, as a model for understanding the imbalance of power that frequently haunts what was called benevolence in the nineteenth century and is more commonly called humanitarian efforts or social activism today. Going back a few centuries gives students perspectives on how racism developed and changed over time. Although we could ask students to directly consider their racial identity and socio-economic positionality in the world, and specifically in their humanitarian efforts, this type of questioning arises more organically when it is done indirectly, as through the nineteenth-century African American literature I have discussed here.

An area of research in psychology called theory of mind examines a person's ability to understand the emotions, thoughts, beliefs, and intentions of others. Developing a theory of mind is considered by some a precursor to developing the capacity for empathy. David Comer Kidd and Emanuele Castano of the New School for Social Research have conducted research suggesting that reading literature improves the intuitive ability to understand others' emotions, thoughts, beliefs, and intentions; in other words, to read other people. Kidd and Castano state, "The worlds of literary fiction are replete with complicated individuals whose inner lives are rarely easily discerned but warrant exploration" (Sapolsky 2013). I would apply the same thinking to the literary tradition I have analyzed and to current social change movements, both replete with complicated individuals whose inner lives we should explore. In 1893, Charles Chesnutt wrote to a friend that "in my intercourse with the best white people of one of the most advanced communities of the United States, . . . hearing the subject of the wrongs of the Negro brought up, . . . I have observed that it is dismissed as quickly as politeness will permit" (McElrath and Leitz 1997, 81). Over one hundred years later, what progress have we made in this regard?

In a country where many people fear talking about race, struggle to facilitate productive or even civil dialogue about race, and would benefit greatly from healing the wounds of racial oppression, the narratives by African American authors discussed here can give us a healthy start. Historian Stephen G. Hall eloquently describes the gift these authors have given:

Nineteenth-century [African American] writers clearly saw themselves as something more than members of disconnected and scattered groups, helpless chattel, or brute, subhuman creatures. They viewed themselves as men and women of intelligence and erudition and as active shapers of the world they inhabited . . . African American intellectuals demonstrated how conversant they were with the wellsprings of American intellectual culture. (233–234)

As an African American intellectual concerned with the moral progress of the American nation as a whole, Chesnutt once noted in his journal that the purpose of his novels was not "so much the elevation of the colored people as the elevation of the whites—for I consider the unjust spirit of caste . . . a barrier to the moral progress of the American people" (Brodhead 1993, 139–140). Chesnutt sought to use literature "to accustom the [white] public mind to the idea of social recognition for black people"(Brodhead 1993, 140). Even his writing is an act of benevolence to white readers.

Many literary critics view African American literature as an integral part of American literature. Among the general public, however, African American literature and American literature are too often viewed as separate entities. The literatures, histories, and fates of black and white Americans are inextricably intertwined. In the words of literary scholar Michael Levenson, "Every site of cultural control and subjugation . . . is also a potential site of agency and change" (Morgan 2004, 15). We have more work to do in order to achieve that transformation; dusting off benevolence texts from nineteenth-century African American literature will help us get there.

Notes

1 I want to thank my reviewers who articulated this much more clearly than I originally had. I also owe a debt of gratitude to Steve Koppi, my spouse and intellectual partner, whose astute reading of and thoughtful comments on drafts of this article substantially improved it during the revision process.

2 See http://hdl.handle.net/1903/13181 for abstract and full text of my dissertation.

3 I use the dichotomous terminology of the nineteenth century, "black" and "white," because that is the language of the literature that I am constantly reading. It also illustrates the legacy that still pervades American society. I firmly believe that the concept of race is socially constructed, but the social consequences of having black or white skin are still all too real. I prefer the term "African American" to "black," and many people who self-identify as being of African descent prefer that term for ideological reasons. As several examples in this article illustrate, the signifiers "black" and "white" are deceptively simplistic. That said, I sometimes use "black" and "African American" interchangeably, a slippage that elides important distinctions. Given that marking racial identity or skin color (again, not the same thing) several times in one sentence can become linguistically cumbersome, I simply often revert to the terms "black" and "white."

4 These friends are racially unmarked in the text, but research indicates that it was one white man and one free African American man who helped him with his escape. He was received by abolitionists who were members of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society in Philadelphia. The abolitionists are also racially unmarked in the text, but the Society is known to have included both black and white members.

5 See Appendix of my dissertation at http://hdl.handle.net/1903/13181 for a complete list of these authors and which works of theirs I examined. From this list I chose my four key texts. Authors included James Fenimore Cooper, Lydia Maria Child, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Herman Melville, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Elizabeth Stuart Phelps, and many others.

6 Authors ranged from Olaudau Equiano, David Walker, and Maria Stuart to Charlotte Forten Grimke, Martin Delany, and Frances Harper.

7 This work is one of five book-length studies that I recognize as key predecessors to my project.

Work Cited

Alcott, Louisa May. 1863. Hospital Sketches. Boston: James Redpath.

———. 1873. Work: A Story of Experience. Boston: Roberts Brothers.

Brodhead, Richard H. ed. 1993. The Journals of Charles W. Chesnutt. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Brown, Henry Box. 1851. Narrative of the Life of Henry Box Brown. Manchester, England: Lee and Glynn.

Brown, William Wells. 2000. Clotel: or the President's Daughter, A Narrative of Slave Life in the United States. ed. Robert S. Levine. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's. Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. 2014. Classification Description: Community Engagement Elective Classification Definition. Accessed March 10, 2014. http://classifications.carnegiefoundation.org/descriptions/community_engagement.php

Center for Teaching. 2014a. "What is Service Learning or Community Engagement?" Vanderbilt University. Accessed March 10, 2014. http://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/teaching-through-community-engagement/#what

———. 2014b. "A Word on Nomenclature," Vanderbilt University, Accessed March 10, 2014. http://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/a-word-on-nomenclature/

Chesnutt, Charles W. 1901. The Marrow of Tradition. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin & Company.

Craft, William, and Ellen Craft. 1860. Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom; or the Escape of William and Ellen Craft from Slavery. London: William Tweedie.

Delanty, Gerard. 2002. "Two Conceptions of Cultural Citizenship: A Review of Recent Literature on Culture and Citizenship." The Global Review of Ethnopolitics 1 (3): 60–66.

Dobbs, Michael. 2005. "Beyond Me: I Wanted to Help, But It's Not That Simple," Washington Post, February 27. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/articles/A55199-2005Feb26.html

Ernest, John. 2004. Liberation Historiography: African American Writers and the Challenge of History, 1794–1861. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. Great Schools Partnership. 2014. The Glossary of Education Reform. Accessed March 10, 2014. http://edglossary.org/community-based-learning/

Hall, Stephen G. 2009. A Faithful Account of the Race: African American Historical Writing in Nineteenth-Century America. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

Hossfeld, Leslie H. 2005. Narrative, Political Unconscious, and Racial Violence in Wilmington, North Carolina. New York: Routledge.

Imagining America. 2014. "Hybrid, Evolving, and Integrative Career Paths. Call for submissions to Public," Vol. 2 Issue 2. http://imaginingamerica.org/blog/2014/01/06/reminder-jan-30-is-the-deadline-for-submissions-to-publics-next-issue/Jacobs, Harriet A. 1861. Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Boston: Published for the author.

Jones, Absalom, and Richard Allen. 1794. A Narrative of the Proceedings of the Black People During the Late Awful Calamity in Philadelphia, in the Year 1793. Philadelphia: William W. Woodward. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HMS.COUNT:1115398

Keckley, Elizabeth. 1868. Behind the Scenes, or, Thirty Years a Slave, and Four Years in the White House. New York: G.W. Carleton & Company. http://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/keckley/menu.html

Koliba, Christopher. 2004. "Is Service-Learning and the Downsizing of American Democracy: Learning Our Way Out," The Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning. 10 (2): 57–68.

Kristof, Nicholas. 2009. "How Can We Help the World's Poor?" New York Times, November 20. McElrath, Joseph R. Jr., and Robert C. Leitz, III, eds. 1997. To Be an Author: Letters of Charles W. Chesnutt 1889–1905. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Morgan, William M. 2004. Questionable Charity: Gender, Humanitarianism, and Complicity in U.S. Literary Realism. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England.

Rice, Andrew. 2006. "Misery Chic," New York Times, December 10.

Ryan, Susan M. 2003. The Grammar of Good Intentions: Intentions: Race & the Antebellum Culture of Benevolence. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Sapolsky, Robert M. 2013. "Another Use for Literature," Los Angeles Times, December 29. http://www.latimes.com/opinion/commentary/la-oe-sapolsky-theory-of-mind-20131229,0,2431766.story#ixzz2t2kgS0Qj, accessed 2/11/14.

Sidbury, James. 2007. Becoming African in America: Race and Nation in the Early Black Atlantic. New York: Oxford University Press.

Troppe, Marie. 2012. "Black Benefactors and White Recipients: Counternarratives of Benevolence in Nineteenth-Century Literature." Ph.D. dissertation, University of Maryland. Accessed January 16, 2014. http://hdl.handle.net/1903/13181.

Yellin, Jean Fagan. 2000. Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

———. 2004. Harriet Jacobs: A Life. New York: Basic Civitas Books.