In every scholarly project that I have pursued, there is an aha moment in which not the answer but the fundamental riddle of what I am investigating becomes clear. It does not occur early in the project, for it depends on the preparatory work of false starts and first research. Nor is it some grand, culminating epiphany. Rather—for me anyway—the aha moment tends to come in a second wave of work, catalyzed by something material and specific, a photo in a folder, a detail in a story, that illuminates a landscape into which I have already ventured. When it happens, the scope and implication of the project begin to sharpen with an almost aesthetic pleasure.

This essay starts in such a moment, one summer day in 2006, in the abandoned mills of Lewiston, Maine. I was visiting the offices of a community history museum—Museum L-A—with which I was collaborating on a traveling exhibition about textile millworkers in twentieth-century Lewiston. I was the director of a center for community partnerships at Bates College (located in Lewiston) and served as the lead faculty investigator for the project. My students had done archival research and examined dozens of oral histories, reconstructing the social world of the largely Franco American workers who had labored in the mills 1. Our team was starting to sketch Weaving a World, as the exhibition would be called, and I was meeting that day to report on our progress and look over a folder of materials newly donated by a retired millworker. It was a document in that folder that prompted my aha moment: an invitation to a 1966 banquet honoring long-time employees of the Bates Manufacturing Company. So startling was the invitation, so unexpected and complex the questions it provoked, that it had the effect of reframing the argument of the exhibition. Or rather, it helped me find the argument in the first place.

The invitation also sparked a second aha. For it illuminated not only the what of our exhibition—the experience of Lewiston's millworkers—but also the how of it: the dependence of our project on collaboration, reciprocity, and dialogue. These values have long been touchstones of the civic engagement movement in higher education, at Bates Colleges and elsewhere. Yet my meeting in the mills suggested something more: that such mutuality between academic and community partners could ground not only institutional values and community-based pedagogy, but scholarly practice as well. The invitation did not turn up, after all, in the gloved quiet of some archive, scrubbed clean of the place that produced it. I was privy to it because of the bonds of work and trust that had brought me to the mills. It had power as a document because it was first of all a gift—one that invited me in turn to bring the scholar's gifts of contextualization and analysis to bear on a community partnership. In illuminating the millworkers' world, it illuminated as well the value of public scholarship—the value of making knowledge with the community, not just about it—in understanding that world.

This essay addresses both implications of that aha moment. It offers an argument about the history of ethnic millworkers in twentieth-century Lewiston, one that challenges the common assumptions with which that history is remembered by community members, outsiders, and scholars alike. And in so doing, it offers an argument for the generativity of public scholarship, one that challenges the marginality of such scholarship not only within the research academy but also within the civic engagement movement. These claims are interdependent—the essay argues for the value of public scholarship by doing it. On the one hand, it speaks in the voice of the engaged historian who, in the course of a local research partnership, discovered fascinating implications for our understanding of modernity—implications salient to both the mill town and the academy. On the other, it speaks in the voice of the civic engagement activist, presenting a brief for the importance of knowledge-making in public. In shifting between those voices, it aims to make audible the internal fugue of the public scholar.

Figure 4: Weave shed, Bates Mill No. 5, Museum L-A Director Rachel Desgrosseilliers with school visit. 2004.

Museum L-A was headquartered in Building No. 5 of the old Bates Manufacturing Company, a weave shed that once housed hundreds of power looms. The building is part of a mile-long complex, stretching down the Androscoggin River from the Great Falls that once formed the economic heart of Lewiston-Auburn. At the height of the twin cities' prosperity, after World War II, tens of thousands of weavers worked day and night in the long, brick structures. Global competition began to shutter the mills in the 1970s; by the summer of 2006, the raw space was being subdivided for small businesses and non-profits like Museum L-A. The museum is in fact a response to this deindustrialization and the historical rupture that resulted. Its mission is to honor social memory and at the same time make historical story-telling a catalyst for economic development and community building (Museum L-A 2007). Claiming space in the mills was a way to reclaim the connection between past and present.

My meeting that day was part of a long-term partnership between Bates College and Museum L-A. For several years, faculty, students, and staff had worked with the museum on oral history, archival, curatorial, and exhibition projects. Anthropology, economics, history, and American studies courses had conducted more than one hundred interviews of retired textile millworkers.2

Students served as summer interns and work-study staff, codifying the collections, working as docents, and conducting education programs; some wrote their senior theses on the museum. College faculty and staff served on the Board of Directors.Weaving a World was an important chapter in this partnership. In 2006, Museum L-A was still a young, raw-boned institution, open two mornings a week, as much an attic as an exhibition space. Its leaders were ambitious not just to collect the raw materials of community memory, but also to interpret them in all their human power. Weaving a World was one of the first efforts to distill, tell, and test such large stories. It portrayed the hardscrabble lives and cultural resilience of the millworkers' world between the Depression and the decline of the textile economy. Designed to be portable—six eight-by-ten panels mounted on pop-up metal stands—the exhibition opened in 2008 and ran for a year in the museum's mill-floor exhibition space, after which it was made available for display across New England and Quebec. It was a prototype—compact and temporary—for stories that the permanent installations would eventually tell.3

I was meeting that summer day with Rachel Desgrosseilliers, the Executive Director of Museum L-A, to brief her on the progress of student research for the exhibition and look over some recently donated materials. Desgrosseilliers is herself a product of the history that the museum aims to honor. Her father worked as a weaver for the Bates Manufacturing Company for thirty-five years, eventually going stone deaf from the clatter of the looms. She has led an extraordinary life of civic leadership: first as a nun with an MBA, who directed Lewiston's Catholic hospital; then as a lay businesswoman who founded an important Francophone cultural festival; and finally, late in life, without any training in museum studies or history, as a museum director dedicated to a labor of love and historic preservation (Desgrosseilliers 2006; Desgrosseilliers, personal communication). Collaborating with Rachel Desgrosseilliers is an education in the riches of civic agency hidden in "ordinary" communities. Collaborating with her on a history museum is an education in the centrality of the past as a repository of that civic agency.

Figure 6: Derelict Jacquard loom, Museum L-A, 2006.

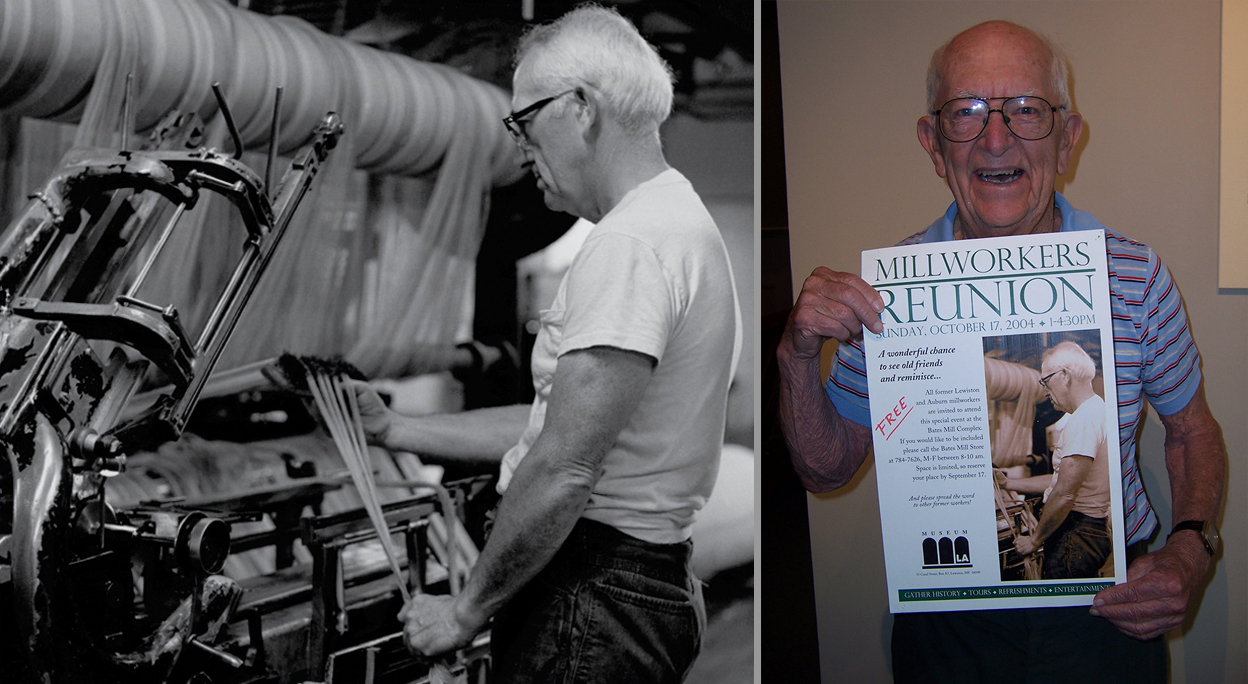

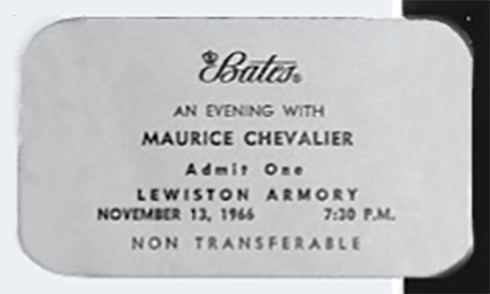

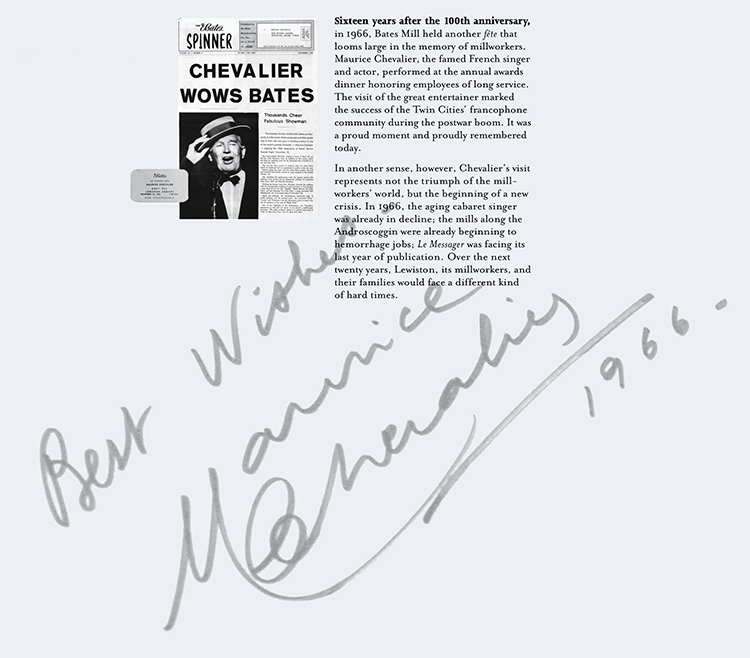

We meet amidst broken looms and photographs, hiring records and newsletters, that she and others have carefully saved from the dumpster. She is showing me her latest treasure, a manila folder of memorabilia donated by Roland Gosselin, an elderly veteran of Bates Mill. Like Rachel Desgrosseilliers, Gosselin has a fascinating story, invisible to outsiders beneath the surface of his life as a retired, nearly deaf weaver. I already know a bit of the lore that surrounds him—that he enjoyed some local celebrity for the community theatricals he produced and the parade floats he created each year for St. Jean-Baptiste Day, an important festival in the Quebecois and Franco American calendar. Opening the folder, we see family portraits of Gosselin's parents and grandparents; all three generations worked in the mills. There is a Christmas snapshot of Gosselin himself in uniform during the Korean War, as well as street photos of the parade floats for which he was famous in town. These are wonderful documents, but they are not surprising. They testify to the importance of family, work, and ethnic Americanism—themes we knew to be central—and I make a note to consider them for selection in the exhibition. And then I take a little breath with the kind of geeky thrill that only the adventures of research can bring. I have pulled out an invitation to a formal gala honoring long-time workers from the Bates Manufacturing Company in 1966. On the back is written, "Best wishes, Maurice Chevalier."

Aha. Or to be more precise, huh? What on earth was the French singer and Hollywood star, by then aging but still world-famous, doing at an employee celebration in a Maine mill town in the 1960s? What led him to autograph the invitation? I was not surprised that Roland Gosselin had preserved this treasure; his donating it four decades later only underscored its personal significance and his trust of Museum L-A as a steward of memory. Yet the social meaning of the invitation, with its long-cherished inscription, brought me up short. It opened a window on the horizons that surrounded the millworkers' world, linking our community partnership with currents of modern cultural history that I have spent many years studying. Why did the urbane Chevalier come to town? What did his visit mean for our understanding of the millworkers' world? And what did it mean that this document had surfaced in a community research project, gifted by a retired weaver? To start to answer these questions, I need to set aside the story of Gosselin's invitation and take up the history of public engagement and public scholarship in American higher education.

III

By the time my career took a turn toward public work in the late 1990s, what we now call the academic civic engagement movement had been going strong for many years. Its history has multiple taproots in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries: the land-grant tradition; the settlement movement; workers' education programs; the lineage of experimental colleges like Antioch, Marlboro, and Hampshire; the demands of Vietnam-era students for educational relevance. In the 1980s, these threads of activism and institutional change came together in a broad effort to renew the democratic and public purposes of higher education, a conjuncture symbolized above all by the 1985 founding of Campus Compact.

In the quarter-century since then, a commitment to civic engagement and community-based educational work has spread across the American academy with astonishing speed and breadth. Campus Compact boasts more than eleven hundred institutional members, and specialized consortia like Imagining America have taken root in nearly every sector of higher education. There are dozens of journals dedicated to public work, community-based research, and service learning. Perhaps most impressive, surveys suggest that some thirty thousand faculty are teaching community-based courses—a number comparable to the size of the largest disciplinary associations (Campus Compact 2010). In a time of tumultuous disruption across higher education, the growth of civic engagement as a movement—not simply a practice—is among the most consequential changes.

It is a sign of our movement's maturity that this growth has catalyzed ongoing discussion about what exactly "higher education for the public good" should mean. The last decade has seen particularly intensive reflection, experimentation, and debate, during which students, faculty, staff, and administrators have developed new ethical frameworks, deeper practices, and more ambitious organizational models. Most fundamental was a sea change in the ethos of the movement, away from service to communities and toward partnership with them. Earlier models of service-learning and volunteerism were critiqued—often by service leaders themselves—for privileging student experience over community benefit and for a charity framework that invited well-intentioned undergraduates to anoint themselves community benefactors. In place of an older paradigm framing "the community" as a landscape of deficits came a new commitment to mutuality and collaboration—a commitment to the view that academic and public partners each bring distinctive needs and assets to their work together. The shift in ethos prompted new models of practice—most of all, a turn away from the self-contained service-learning course toward sustained, integrative projects. Multidisciplinary and multiyear, such partnerships would be educationally transformative, offering faculty the opportunity to weave together broad areas of the curriculum in problem-based education, offering students the opportunity to weave together their intellectual, personal, and civic development. Equally important, they would be socially transformative—deep enough and long enough to link practical community needs to systemic issues of policy, power, and justice. This expansion in the scale, duration, and ambition of public work in turn required new organizational agencies within colleges and universities. The Harward Center for Community Partnerships at Bates College was only one of many dozens of centers and programs founded in the past two decades to support civic engagement across the curriculum, to coordinate public work on campus, and to serve as the "address" for community concerns and relationships.

In short, the civic engagement movement has evolved values, practices, and strategies that embedded public work in curricula, in the internal organization of academic institutions, and in the consortial landscape of US higher education. At its best, it has not only deepened student learning but also worked with communities to solve public problems and co-create public cultural resources like Weaving a World. Yet for all these achievements, I would argue that the movement has languished in advancing public scholarship, especially faculty-led public scholarship. Even among engaged faculty, we tend to bring our students into the public sphere more readily than we bring our own scholarly gifts and energies. We do not always trust that community partnerships and public work will be generative for our knowledge-production and writing—or trust that our deans and chairs and fellow scholars will agree.

Of course, such a summary claim requires some qualification. There are strong counter-traditions of action research and community-based scholarship in the social sciences and the helping professions. There are new service-learning and outreach journals, as I noted above. And many institutions offer rich opportunities for undergraduate community-based research, often yielding important student contributions to project partnerships. (See, for example, "Community-Based Learning Initiative," Princeton University; "Community-Engaged Research," Bates College.) Conversely, it is undeniable that faculty have very good reasons not to focus their scholarship on the public and its problems and its stories. The state of play within most disciplines and the reward system within most institutions tend to incentivize scholars to disengage their intellectual curiosity from their civic and community life. Academic socialization is not an iron cage, but it is a river current, and it is exhausting to swim upstream for very long.

Yet, even taking account of these counter-examples and extenuating causes, I would argue that public scholarship remains an afterthought—or an unfinished task—of the civic engagement movement. We have not committed ourselves deeply and collectively, in sustained practice and theoretical reflection, to the notion that democratic citizenship and academic scholarship require each other and will deepen each other. And that is a shame. For civic engagement will flourish in the American academy only when scholars take seriously our gifts of knowledge-making and meaning-making as democratic gifts, meant to be offered for and with public collaborators; and only when our colleagues, our disciplines, and our institutions reward such gifting as legitimate and productive. This entails something more than convincing colleagues to swim against the current; most scholars do not want to live like salmon. It means re-directing the inertial push of academic socialization, not by abandoning our commitment to scholarly and creative work, but by understanding civic life as a medium for such work. It means bringing into public the capacities that make us scholars and artists: intellectual curiosity, analytical subtlety, research craft, doggedness, playfulness, and passion.

Until we do, until we trust (and demonstrate) the intellectual value of civic engagement, we will collude in keeping our democratic commitments marginal within the academy. What is more, we will shortchange our public collaborators, depriving them of the full measure of our attention. And by missing the opportunity to include them in our community of inquiry, we will deprive ourselves of the questions and discoveries that they catalyze—deprive ourselves of the encounter with Maurice Chevalier. It was, after all, because of Bates' partnership with Museum L-A that I was able to be there in the mills to open Roland Gosselin's folder. It is because of my academic vocation that I can help make sense of what was inside.

How is it, then, that Gosselin came to have the invitation signed by Maurice Chevalier? Research began to provide some answers. The oral histories turned up many reminiscences of Chevalier's performance at a November 1966 Service Awards banquet, hosted by the Bates Manufacturing Company (G. Bergeron 2006, 9; Morin 2006, 6). It was Roland Gosselin who contacted the singer, as he himself confirmed.4 His oral history adds more detail:

[W]hen Maurice Chevalier came to Lewiston, I was [volunteering] for [the local community] theater so . . . I was the head man at the Armory for the set up and the lights for Maurice Chevalier. And I, of course I talked to Maurice Chevalier and he . . . gave me his autograph. And Bates [Mill] had given him a floral to-do . . . in the backstage room where he was, and he gave it to me to bring it to my mother. . . . I still have the dish [for the] floral arrangement. . . . (Gosselin 2005, 8)

The company newspaper offers an enthusiastic glimpse, probably also penned by Gosselin, of the gala. "The Lewiston Armory rocked with cheers as thousands of enthusiastic Bates employees and their guests . . . gave a standing ovation to one of the world's great showmen," the Bates Spinner reported under the headline "Chevalier Wows Bates." "Jaunty and debonair, the world-famous entertainer sang of youth, romance, and the passing years" (Bates Spinner 1966; Gosselin 2005, 8). In the most literal sense, then, answering the question of why Chevalier had come to town was straightforward. He was performing for his public, and Roland Gosselin, the de facto festivities impresario of Franco Lewiston, had done much to make it happen.

Yet the invitation also suggested issues more complex than the mere fact of Chevalier's appearance. It underscored the cultural ambition of the local Francophone community in its heyday, as well as the pride with which its achievements are recalled today. With its heavy stock and scrawled signature, the card added gravitas, the aura of the artifact, to our exhibition. George Washington slept here; Maurice Chevalier sang here. In that sense, Chevalier came to town for just the same reason that, during the depths of the Great Depression, Lewiston's Franco American working class funded the construction of the grandiose Basilica of Saints Peter and Paul, the second largest church in New England (Thomas and Ward 1999). Both were monuments to the community's "survivance," as Franco elders put it, evidence of the heft of its enduring identity.

Survivance: One cannot make sense of the millworkers' world and how it is remembered without understanding the resonances of this key word. It expresses a core value of the French Canadian and Franco American experience—not simple survival, but a commitment to the sustaining of identity, solidarity, and culture in the face of defeat, displacement, and external pressure. Against the Anglo Canadian supremacy and the Acadian expulsion, against the hardships of emigration and industrial labor in Gilded-Age America, against the whiplash of ethnic denigration and then middle-class assimilation in the twentieth-century US—against all of these challenges, survivance was a communal battle-cry for ethnic institution-building, cultural protectionism, Catholic loyalism, and linguistic preservation. Like the Jewish story of the exodus, the discourse of survivance has been supple and adaptable, offering a metanarrative in which the sheer heroism of Francophone resilience in the face of past defeats and present dangers has guided the community through history.

Yet the word was as much a call to action as a frame for memory, especially in New England, where hundreds of thousands of French Canadians emigrated between 1880 and 1920. Every mill town had its "petit Canada" district, its Francophone newspaper, its fraternal associations, its French Canadian parishes and parish schools, often as resistant to the Irish church hierarchy as to Protestant hostility (Gosnell 2007, 1345; Jacobson 1984) So central was "the Survivance Movement" to Franco American social history, that it provided the organizing paradigm for the first wave of academic research into that history—often by scholars with personal roots in the community. "Franco American historiography . . . has emphasized the centrality of 'La Survivance' to the immigrant generation's migration and acculturation experience," notes oral historian Celeste DeRoche, "recount[ing] the institution building that became the centerpiece of an heroic effort to maintain French Canadian cultural, religious, and ethnic integrity" (DeRoche 1996, 45).

Survivance proved an essential theme of Weaving a World, informing our community partners' understanding of the project, student research, and my own analysis in drafting the script. The exhibition brought together a rich array of materials—some donated by retirees, others unearthed by Bates undergraduates—that laid out the infrastructure of survivance in Lewiston-Auburn. There were sports pages from Le Messager (the Francophone daily published until the late 1960s); photographs of snowshoe clubs, parish classrooms, and St. Jean-Baptiste Day parades; oral vignettes of ethnic loyalty and interethnic conflict. "Millworkers made more than just bedspreads," one panel explained:

They created a close-knit community of families, neighborhoods, and ethnic and religious institutions. Their social life could be insular and even defensive. Yet the ethic of loyalty and mutual care enabled millworkers to endure the hardships of migration and economic depression. Franco-American elders have a phrase for this experience: la survivance. The phrase means something deeper than mere survival, more than just the capacity to outlast adversity. La survivance marked a kind of stubborn resilience that, in the hard times of the early 20th century, created a rich communal world.

All this underscored the significance of Roland Gosselin's invitation. For the act of bringing a Francophone icon to honor veteran millworkers was itself a celebration of this "stubborn resilience," an act of survivance. And so was preserving the card that Chevalier autographed, and so was gifting it to Museum L-A forty years later. Survivance was not just a theme of Weaving a World; it was one of the project's constitutive goals. The exhibition reconstructed a social world that had sustained identity and community in the teeth of the mill economy. And by telling that story, it would continue to sustain identity and community in the aftermath of that economy.

V

Yet there is something too neat in subsuming Chevalier's visit under this theme. For even at their proudest, invocations of survivance always carried an undertone of insularity, of defensiveness and defiant provincialism. They told a story of stubborn Franco resistance to the threatening realities of the wide world. And if the invitation signified anything, it was precisely Lewiston's connections with the wide world, a world where international performers, mill town banquets, and immigrant workers were somehow interwoven. The invitation posed questions about the interconnections between local ethnic communities and mass culture that the framework of survivance could not fully explain—questions on which I could bring to bear other resources. For, as it happened, Chevalier's visit engaged important issues within my academic community.

Cultural studies scholars long tended to assume that the institutions of commercialized amusements and consumer culture—the world of Maurice Chevalier—were fundamentally homogenizing. The effects of mass culture, it was argued, could be extrapolated from the metropolitan centers and corporate purveyors from which it was delivered to places like Lewiston, Maine (see, for instance, Lears 1994; Leach1994; Sklar 1994). Other research, however, has challenged this unidirectional model. American studies scholars have unpacked the ways in which ethnic, class, rural, and regional communities responded to the forces of consumerism and mass culture, refracting its messages, making it their own (Cohen 1990; Heinze 1990). Scholars of globalization have explored the ways in which diasporic communities—Vietnamese immigrants, for instance—create distinctive "glocal" realities linked by transnational circuits of media, consumption, and style (Lieu 2011; Robertson 1995).

Such research points to the distinctive agency of supposedly provincial places like Lewiston within the supposedly homogenous landscape of celebrity and entertainment. It suggests that Chevalier's visit might have been part of a Francophone geography that linked Quebec, the Francophone US, France, and other places in a common cultural archipelago. It intimates that Gosselin's invitation might have been part of a larger dialogue among metropolitan and non-metropolitan milieus, a circuitry of needs and affiliations, which complicates our conventional wisdom about "cosmopolitan" and "provincial" communities. Were Franco-Mainers paying homage to Chevalier, to the influence of Hollywood, Paris, and Manhattan in their lives? Was the singer paying his dues to the local worlds—especially bilingual worlds--within which he had to seek a following?

These are an academic's questions, far from the concerns of Roland Gosselin and Rachel Desgrosseilliers. They are provoked by my peculiar position on the borderlands, so to speak, between my community partners and my scholarly colleagues. The civic engagement movement needs to inhabit those borderlands not only for teaching and public problem-solving, but also for scholarly work. I left Museum L-A that summer day prompted to revisit some of the most interesting issues in modern cultural history: issues concerning the lived experience of modernity and the interweaving of local, national, and transnational affiliations; issues that brought together students of US consumer culture, sociologists of globalization, historians of Quebecois emigration. The invitation was inviting me to act as the "scholar" in "public scholar."

Which would also strengthen, of course, the public value of my academic work. By owning the scholar's voice, by carrying its debates and literatures into the mills with me, I could bring new insights to bear on the needs of my partners. The researcher's lens is often diminishing and reductionist, we know. Yet if framed by an ethics of collaboration, it can be illuminating and empowering—even when it challenges the received wisdom of our community collaborators. The story of Chevalier's visit presented an opportunity (even a responsibility) to push back at the received picture of Franco American community as local, insular, and defensive—a picture shared by insiders, outsiders, and historians alike. It suggested instead a complex play of local and global forces, of communal loyalties crosscut with cosmopolitan connections. A mill town company invited an international icon to town, mobilizing his urbanity to celebrate itself and its workers—all staged by a local weaver and community impresario. It required the gifts of both Franco American memory and cultural studies to bring that complex reality into focus.

Figure 10: Parade float, St. Jean-Baptiste Day, date unknown. Roland Gosselin, standing at right, designed the float.

VI

This dialogue between my partners and my colleagues ended up recasting the argument of Weaving a World. But first it prompted more research and reflection. It led me to look for other evidence where the hardscrabble lives and communal bonds of survivance were interwoven with stories of inventiveness, creativity, and cultural boundary-crossing. The oral histories turned out to contain many such stories. Some described everyday acts of self-fashioning and even transgression in the face of local norms. "I came back from the Army and went to the mill," Cecile Burgoyne recalls of her World War II experience in the Women's Air Corps. "And at that time I brought back my fatigues, . . . and I wore pants [to work]. Of course it was the talk of the town, but I didn't care!" (Burgoyne 2005, 4)

Lionel Audet was less rebellious, but his oral history told a complex story of constraint, obligation, and self-initiative. One can hardly imagine a background that more fully embodied the survivance narrative. Audet's father, an immigrant from rural Quebec, worked in the Androscoggin Mill for two decades, raising nine children on the outskirts of Lewiston as a widower. Audet vividly describes a childhood without indoor plumbing or heating, with patriarchal priests and interethnic scrapes between Irish and French Canadian boys, but also with crucial moments of communal care:

My father was making eleven dollars and seventy-five cents a week, so he couldn't afford to hire anybody to take care of us. . . . One week I would stay home and take care of the three-year old [brother and] the next week I'd go to [high] school. . . . So, I wasn't going to graduate. So this nun that I had she says, you can come in any time you want. You got time at night, Saturday or Sunday . . . I'll spend all the time I can with you to try to get you caught up. And she succeeded . . . I didn't graduate with honors, but I graduated. If it hadn't been for her, she was like a mother to me. (Audet 2006, 16)

Audet seemed destined to follow his father into a lifetime on the mill floor, until World War II intervened. After four years in the service, the once-desultory high-schooler used his discharge benefits to take correspondence and night courses on business and textile production. He entered the Libby Mill as a sweeper and bobbin boy, but within a few years, he was asked to be a supervisor and began mastering the mill's processes, department by department. He retired forty-four years later as the plant manager (Audet 2006).

These lives were lived at once within and without the millworkers' world. They straddled and tested its limits, shifting and sometimes challenging the social dispensations of class and gender for which members of the community were supposedly meant to settle. The results could sometimes transform not only the individuals themselves, but also the community as a whole. Consider the story of Henry Goulet, a Depression-era loom tender who had worked in the very weave shed where I first visited Museum L-A. It was Goulet's innovative tinkering on Jacquard looms in the Bates Mill that enabled production of the famous Bates bedspreads, with their nubbly, intricate designs, on which the Lewiston textile economy depended after World War II (Sun Journal) 1999; Fred Lebel, personal communication). The most popular of these designs, the George Washington bedspread, was a fixture in American middle-class bedrooms during the 1950s and '60s, sold in department stores, on wedding registers, and through the Manhattan showroom of the Bates Manufacturing Company—always with a tag that read "Loomed To Be Heirloomed." ("Most Famous Bedspread" n.d.) It is no exaggeration to say that this immigrant inventor saved Lewiston from the decline that other New England mill towns suffered in the face of Southern competition. Goulet's innovations staved off deindustrialization for fifty years.

Yet the most striking stories in this archive of self-agency were not about upward mobility and shop-floor entrepreneurship. They involved solidarity and empathy that crossed the barriers of ethnicity and faith. Survivance, after all—the sustaining of identity, language, and memory in the face of external threat—might always devolve into tribalism. Even today, in the weave shed of the Bates mill, you can see stenciled rows of green shamrocks and blue fleur-de-lis that testify to the ethnic divisions of the millworkers' world. And yet, there were also many stories in which such divisions were overcome: a shop-floor translator who conciliated resentments among Anglophone and Francophone weavers, or the refusal of a Franco youth to strikebreak against the (largely Anglophone) shoemakers in the great Auburn strike of 1936 (Frechette 2006, 5–6).

World War II was a particular crucible of change, dissolving communal divisions in the solvent of national conscription and global conflict. "My four years in the service [were] a major education," Lionel Audet recalls. He had been reared to believe that "you don't associate with anybody that's not Catholic, . . . because, you know, anybody that's not Catholic is going straight to hell." Military service broke open this parochialism:

I had never . . . slept away from home overnight once. . . . So now I'm in [with] . . . Polacks, Irish, Lithuanians, Italians, . . . Germans, Russians . . . all in the same company. . . . I realized . . . we're all actually worshiping the same God basically. . . . [T]his business, you know, being the only way you go to heaven is you have to be a Catholic, that's a lot of hooey. (Audet 2006, 16)

The war provided an even more searing lesson to Emeril Bergeron. He took part in the liberation of Buchenwald:

[T]here was a place, a round building, it was all cement, . . . and they had small benches here and there, and a rope. So they'd stand the prisoners on that, tie the rope, and then one guy would go by, after they were all tied up, he'd kick the bench off and they'd hang. Can you imagine a human being, and as smart as the Germans were, to do that? . . . [F]or a person that had never been . . . out of Lewiston, it's quite a thing to . . . just see those bodies, you know. (E. Bergeron 2006, 21)

Such evidence may seem too anecdotal, too exceptional. Few millworkers' children after all grew up to be plant managers; fewer retooled the looms or witnessed the horrors of the Holocaust. These stories were largely known in community lore, but they were known as curiosities, as granular vignettes, not as touchstones of social memory. It was Gosselin's invitation that prompted us to lift them up, connect them, and interrogate their meaning. Taken together, they challenged the notion of a proud but insular community girding itself against a host of external threats. Rather the research suggested the opposite: that the currents of the wide world—the nationalizing effects of patriotism and war, the enticements of mass culture, the assimilationist pressures of education, economic growth, and consumerism—were already present inside the community, like Chevalier at the gala, inflecting its traditions, crisscrossing its institutions, redefining the terms of survivance. It suggested that community members engaged this hybrid reality with dynamic, creative, sometimes transformative acts of self-making, change-making, and boundary-crossing. And they did so precisely as loyalists within the community, whose loyalty reflected not insularity and reaction, but rather an expansive embrace of American modernity that wove a new kind of tough-minded, cosmopolitan localism through the millworkers' world.

VII

No one exemplified this complex reality more than Roland Gosselin. He started work as a sweeper in the Bates Mill at sixteen—the youngest one could be legally hired—but quickly learned industrial weaving from veterans on the shop floor. At the same time, he developed what would become a lifelong passion for music, theater, and stage design, fueled by early visits to New York City. "I was only sixteen, seventeen years old when I went to the Metropolitan Opera, to the opera, and so I started loving classical music," he recounts in his oral history. Like Lionel Audet, military service took Gosselin away from the shop floor and Lewiston—and surprisingly, enabled him to connect his love of the theater (and New York City) with new aspirations. On a furlough with friends in Manhattan, he began to search for work, hoping to use his penchant for design and spectacle to make a living as a store decorator and window-dresser: "[M]y idea was to go work in New York and then to go to school to learn decorating and do the decorations in [department] stores" (Gosselin 2005, 6, 7).

Soon after his discharge, Roland Gosselin did in fact receive an offer "from one of the leading men's department stores" (Gosselin 2005, 2). Yet, by a cruel irony, it came just a few days after the death of his father. He was the oldest of nine children, and he turned down the Manhattan offer, returning to his weaver's job at the Bates Mill to take care of the family. "[When] all my brothers . . . got married, I was the one, [the] witness for them because my father was already dead . . . I was the father image, [and] whenever they got married, I gave them big prizes" (Gosselin 2005, 7). Gosselin did not abandon his love of music, theater, or New York City. He amassed a record collection of more than five hundred operas. He produced plays for the local Catholic high school, created his famed parade floats for St. Jean-Baptiste Day, and designed many community drama productions. "So this is how come I joined [the Lewiston-Auburn] Little Theater," he explains, after recounting the story of the lost position in New York, "as an outlet, as an outlet . . . I worked on the first musical they did, Showboat, and then, and we went along and then I remember I did Carousel, I did The King and I, I did Song of Norway, I did Fiddler on the Roof." He made annual pilgrimages to Manhattan to attend the Broadway theater and the Metropolitan Opera: "I used, every year I used to take a week and go to the plays in New York, I used to go see three, four plays, I used to go to the opera, see one or two opera. And that was like an offset for me, to do that. And a lot of this was done alone. I used to travel alone, I used to go alone and come back" (Gosselin 2005, 6, 7).

I did not know Roland Gosselin well, and I do not want to sentimentalize his experience. In one sense, his is a common American working-class story—that of the unfair distribution of life-chances and the generous, resilient ways in which people make the best of those chances as they honor their attachments to family and community. What he made of his circumstances was quite remarkable. Gosselin served as President of the Lewiston-Auburn Little Theater and of the Richelieu Club, a Franco American fraternal association. After many years as a weaver, he became the business agent for the textile workers' union local in the Bates Mill. He edited and wrote for the Bates Spinner, the company newspaper (Gosselin 2005). And his literacy was valuable in another way. It was well-known among unlettered millworkers—Rachel Desgrosseilliers' father was one, and she herself explained this to me—that Roland Gosselin would teach you to sign your name or personally endorse checks and paystubs for you. Yet in another sense, these achievements make Gosselin's story all the more heartbreaking—one of lost chances "offset" (as he puts it) in solitary pilgrimages to New York and the public pleasures of community theater.

His life, in short, embodies the weave of communal bonds and boundary-crossing that characterized the millworkers' world. It is this complexity at which the story of the invitation hints. Maurice Chevalier was an apt symbol for it. By the time he visited Lewiston, his career was itself a Franco American hybrid, a simulacrum of "Parisian" sophistication presented (alongside Piaf songs and Cartier-Bresson photographs) to a largely American public. His performance drew on this persona, mixing cabaret standards, Hollywood hits, and "a salute in song to the city of Lewiston, to the tune of 'Hello, Dolly'" (Bates Spinner 1966). The adoring audience in the Armory would have felt itself addressed as bilingual citizens of a trans-Atlantic republic of song. All of this was tacit, of course. Millworkers' memories do no more than invoke the feeling-tone of importance that the star's presence bestowed (G. Bergeron 2006, 9; Morin 2006, 6). Yet for Roland Gosselin, the gala was a signal event in a life of family and community loyalty mixed with a quiet, sometimes secret urbanity. His oral history dwells on the importance of Chevalier's visit, and yet he does not parse its personal meaning (nor connect it to his own visits to New York) (Gosselin 2005, 8). All we learn is that he designed the stage and lights for the concert, and that Chevalier thanked him with the autograph that he donated to Museum L-A forty years later. Would Roland Gosselin have found my reading of the invitation—my sense that it illuminated the history of his community in unexpected ways—self-evident, or outlandish, or just a bit overdone? I have no idea. I do know that it reshaped our exhibition.

VIII

Weaving a World comprises six panels, eight feet high and ten feet long (along with a smaller, introductory panel). These are affixed magnetically on the front and back of freestanding, pop-up aluminum matrix structures. When the pop-ups are collapsed, and the digitized panels rolled in strips, the exhibition stores in seven plastic barrels that fit into a minivan. When it is fully assembled—which takes about three hours—visitors walk through an array of gently curved, high display walls, sequenced in chronological and thematic order. Each panel is a digitally printed ensemble of interpretive text, oral history passages, photographs, documentary visuals, and captions.

The panels can be viewed here.

The exhibition offers an account of the millworkers' world that mirrors the complexities and tensions uncovered in Gosselin's story. The first half unpacks the forces shaping the mill economy in the early twentieth century: water power, the technologies of loom and mill, the harsh realities of Quebecois emigration, industrial labor, and economic depression. It portrays the social world within which millworkers sustained themselves in and against these conditions. There are photographs of hockey leagues and snowshoe clubs, maps of ethnic enclaves, memories of communal support like Lionel Audet's struggle to complete high school. The second half, moving forward to wartime and postwar Lewiston, complicates this account of survivance, exploring the ways in which millworkers engaged the wider currents of American modernity that cut across their community. We learn of Franco American patriotism, of working-class home ownership, of the cross-ethnic realities of upward mobility, consumer culture, and trade unionism. Cecile Burgoyne's rebellious dress practices are recalled, as well as Lionel Audet's military service, Henry Goulet's inventions, and the George Washington bedspread. Of course we see Roland Gosselin's invitation to "Admit One" to "AN EVENING WITH MAURICE CHEVALIER," and below it, digitally lifted and enlarged, the scrawled words, "Best wishes, Maurice Chevalier 1966."

The exhibition concludes with the mill closures and deindustrialization that made the historical reclamation of the millworkers' world so important—and the emergence of a community commitment to public memory that made it possible. It culminates, in short, with Museum L-A as itself the next chapter in the story of survivance and change. Two photographs of Rachel Desgrosseilliers, side by side, capture this shift from the history of work to the work of history most vividly. In one, the young nun smiles, next to her father on the shop floor; in the other, the contemporary museum director addresses a crowd of visiting schoolchildren in the old weave shed of Bates Mill No. 5 (See Fig.3 and Fig. 4).

Weaving a World, in short, bears the traces of the dialogue that produced it. It is the outcome not simply of an institutional partnership between a liberal-arts college and a local museum, but of an intellectual exchange between communal memory and academic scholarship—an exchange that deepened and complicated both. The exhibition challenges the received notion that the ethnic mill town sustained itself through proud, stubborn resistance to the wide world. It challenges the received notion that mass culture, consumerism, national politics, and deindustrialization were solvents that simply disembedded ethnic millworkers and their families from their communal identity. And in the process, it presents a story in which communal memory is both commemorative and transformative, both inward- and outward-facing, both local and cosmopolitan—both in the heyday of the mill economy and in its aftermath. That was the point of Roland Gosselin's story, after all: the millworkers' world already contained within itself the dialectic of Broadway and Bates Mill. Only in the dialectic of public scholarship could the full complexity of that world come clear.

IX

All scholarly work takes place in communities of inquiry and practice. Through them we construct and contest and recast, ongoingly, what counts as useful knowledge, good questions, strong answers. Within the academy, these communities are largely constituted by disciplinary expertise; their regimes of peer assessment, professional associations, and specialized publications determine how knowledge gets pursued, produced, and validated. The practice of public scholarship has the potential to enlarge the process, by including non-academic collaborators in the community of practice, by redefining who counts as a peer. The burden of my essay has been that such an enlargement of the circle, such a commitment to academic-community reciprocity and dialogue in the pursuit of knowledge-making, is generative for both scholarly work and community life.

This claim has implications beyond the story of Lewiston's millworkers. Taking public scholarship seriously means disrupting long-cherished norms about how research is formulated, where and how it is presented, how and by whom it is evaluated. It means challenging disciplinary orthodoxies that have cast a cold eye on public collaboration as a threat to their authority and rigor. Happily the academy boasts many models of great scholarship grounded in the public work of their authors. In my own field, E. P. Thompson's magisterial Making of the English Working Class could not have been written except in response to his activism and trade-union teaching; C. Vann Woodward's paradigm-breaking Strange Career of Jim Crow was catalyzed by research for civil rights litigation during the 1950s. To be clear, there is a humbling distance between these masterworks and Weaving a World. Yet to be equally clear, the legitimacy of engaged scholarship should not depend on its attainment of masterwork status. Rather, I would argue, we want an academy in which support (not mere acceptance) of public scholarship permeates our institutions and our disciplines.

Taking seriously the intellectual value of public work—the scholarly value of listening to Roland Gosselin—means opening the institutional space for new kinds of faculty careers and research practices. We will need, of course, meetings in the mills: times and spaces for reflective conversation with community partners about the intellectual implications of our partnerships. We will need new and rigorous models of tenure and promotion that incentivize, assess, and reward excellence in such engaged work (Ellison and Eatman 2008). We will want to experiment with new genres of writing and exhibition (and the development of innovative publication platforms like Public). We will want to revisit the ethics of research, amending policies—for instance, those on intellectual property and human subjects—that presume the autonomy of the research scholar and the passivity of the research subject. ("Roland Gosselin" and "Rachel Desgrosseilliers" are not pseudonyms but the names of actual partners and peers, whose story I tell with their permission.)

For some scholars, all this may seem too much, placing at risk important safeguards of the scholarly vocation. It asks faculty to reconceive the social compact that governs our labor and our access to resources, not by making public engagement a goal of every scholar's work, but by making it a collective commitment of our institutions. And so it is important to remember that engaged scholarship will be a joy as well as a responsibility, calling on us to be playful, exploratory, curious, and rigorous. Anyone who has taught a service-learning class knows the exhilaration that our students express when they "get out of the bubble," as the saying goes, activating liberal learning in the practice of public life. As public scholars, we too will be vivified by closing the circuit between our intellectual vocation and our civic life, jazzed (as I was that day in the mills) by whom we encounter and what we discover in the borderlands.

X

In writing this essay, I suddenly remembered that my father used to sing to my brother and me, in his burlesque way, a hit of Maurice Chevalier's from his Depression-era childhood: "If ze nightingale could sing lak you, he'd sing much sweeter zen he do/Cause you brought a new kind of love to me." Only in researching Maurice Chevalier's career did I figure out why it was that If The Nightingale Could Sing Like You stuck in my father's head so much that he would croon it to his young sons thirty years later. The answer, curiously enough, involves the Marx Brothers. There is a scene in Monkey Business in which the brothers need to disembark a cruise ship in New York and have lost their passports and are stuck. It turns out that none other than Maurice Chevalier himself—playing himself—is on board, and that Chico has pinched the singer's papers. One by one, each brother presents the stolen passport, and certifies to skeptical customs officials that he is Maurice Chevalier by singing, "If ze nightingale could zing like you." Even the mute Harpo straps a gramophone on his back and lip-synchs Chevalier's own performance.

It is a wonderful moment: immigrant Jews appropriating a more famous voice for their own purposes, as Bates millworkers would do decades later (Lieberfeld and Sanders 1995, 104). So was finding it on YouTube. Not quite the aha revelation of Gosselin's invitation, but a moment that illuminated why my father, who adored the Marx Brothers, ended up giving me my own little token of Maurice Chevalier. And not coincidentally it seems exactly the right way to end an essay about and of public scholarship. For above all, a public scholar needs to learn what both Chevalier and the Marx Brothers knew: how to cross borders and sing in many voices.

Acknowledgements

This essay (like the exhibition it discusses) has benefited from many institutions and individuals. I am grateful to Museum L-A for permission to draw on its oral history and archival collections, as well as the University of Southern Maine/Lewiston-Auburn College, the Lewiston Public Library, the Androscoggin Historical Society, and the Muskie Archives, Bates College for use of their archival holdings. Most of the documentary research was done by Bates students in my History In the Public Sphere seminar (2006, 2008); I want especially to recognize Thomas Burian, Jessica Dumas, Nate Purinton, Eliza Reed, Julia Simons, and Mike Wilson.

An embryonic version of the essay ("Making Use of All Our Faculties: Public Scholarship and the Future of Campus Compact") was commissioned for an online anthology of "think-pieces" for the twentieth anniversary of Campus Compact; my thanks to Compact for inviting me to contribute. Revised versions were presented at Bowdoin College, the University of Denver, the University of Miami, the University of Richmond, Ohio State University, Duke University, and Concordia University (Montreal). I am grateful to the many listeners and readers who offered feedback, especially Robin Bachin, Erica Lehrer, Steve Conn, Megan Granda, and Stephanie Browner.

This is not the place to acknowledge all those who contributed to Weaving a World: Lewiston's Millworkers, 1920–2008; they are credited in the exhibition itself. Three individuals, however, deserve special thanks. Professor Hannah Smotrich (Stamps School of Art and Design, University of Michigan) designed Weaving a World with nuance and empathy, deepening my understanding of the millworkers' world as she gave it graphic form. Rachel Desgrosseilliers, the Executive Director of Museum L-A, has been an inspiring partner since our first brainstorm about a traveling exhibition that would "show the heart" of the millworkers' world. No one embodied that heart better than Roland Gosselin, whose gift of a keepsake to Museum L-A proved so central to this work of public scholarship. I hope that my story does honor to his.

Works Cited

Audet, Lionel. 2006. Interview. Student Mill Worker Oral History project, Museum L-A Collection. Bates College. "Community-Engaged Research," http://www.bates.edu/harward/cbl/community-based-research/.

Bates Spinner. 1966. "Chevalier Wows Bates." November.

Bergeron, Emeril. 2006. Interview. Student Mill Worker Oral History project. Museum L-A Collection.

Bergeron, Gerard. 2006. Interview. Mill Worker Oral History project, Museum L-A Collection.

Burgoyne, Cecile. 2005. Interview. Student Mill Worker Oral History project, Museum L-A Collection.

Campus Compact. 2010. Annual Membership Survey Results: Executive Summary. Boston, MA: Campus Compact.

Cohen, Lizabeth.1990. Making a New Deal: Industrial Workers in Chicago, 1919–1939. New York: Cambridge University Press.

DeRoche, Celeste. 1996. "'I Learned Things Today That I Never Knew Before': Oral History At the Kitchen Table." Oral History Review 23 (2): 45–61.

Desgrosseilliers, Rachel. 2006. Interview. Student Mill Worker Oral History project, Museum L-A Collection.

Ellison, Julie, and Timothy K. Eatman. 2008. "Scholarship in Public: Knowledge Creation and Tenure Policy in the Engaged University." Imagining America: Artists and Scholars in Public Life. www.imaginingamerica.org.

Frechette, Emile. 2006. Interview. Mill Worker Oral History project, Museum L-A Collection.

Gosnell, Jonathan. 2007. "Between Dream and Reality in 'Franco-America.'" The French Review 80 (6): 1336–49.

Gosselin, Roland. 2005. Interview. Mill Worker Oral History project, Museum L-A Collection.

Heinze, Andrew. 1990. Adapting to Abundance: Jewish Immigrants, Mass Consumption, and the Search for American Identity. New York: Columbia University Press.

Jacobson, Phyllis L. 1984. "The Social Context of Franco-American Schooling in New England." The French Review 57 (5): 641–56.

Leach, William. 1994. Land of Desire: Merchants, Power, and the Rise of a New American Culture. New York: Random House.

Lears, T.J. Jackson, 1994. Fables of Abundance: A Cultural History of Advertising in America. New York: Basic Books1995.

Lieberfeld, Daniel and Judith Sanders. 1995. "Here Under False Pretenses: The Marx Brothers Crash the Gates," American Scholar 64 (1): 103–108.

Morin, Lilliane. 2006. Interview. Mill Worker Oral History project, Museum L-A Collection.

"Most Famous Bedspread in the World, The." n.d. Museum L-A Collection.

Museum L-A. 2007. "Our Vision." http://www.museumla.org/Our-Vision.

Princeton University. "Community-Based Learning Initiative." http://www.princeton.edu/cbli/.

Robertson, Roland. 1995. "Glocalization: Time-Space and Homogeneity-Heterogeneity." In Global Modernities, edited by Mike Featherstone, Scott Lash, and Roland Robertson, 25–44. London: Sage Publications.

Sklar, Robert. 1994. Movie-Made America: A Cultural History of American Movies. New York: Vintage Books.

Sun Journal. 1999. "Bates Mill Recovers from Depression." September 25.

Thomas, E, Donnall Jr., and Ellen MacDonald Ward. 1999. "The Cathedral That Nickels and Dimes Built." DownEast Magazine, January.

Notes

1 Bates students did archival research for Weaving a World, and helped to distill its themes and structure, in my seminar History in the Public Sphere, taught in the spring semesters of 2006 and 2008. Student teams also worked as summer researchers on the project in 2006 and 2007.

2 After a widely attended millworker reunion in 2004, students in courses taught by Professors Margaret Creighton, Elizabeth Eames, and Heather Lindkvist interviewed retired millworkers. The oral histories were donated to Museum L-A and collectively archived as the Student Mill Worker Oral History project. The museum also received grant funding to commission oral historian Andrea L'Hommedieu to conduct several dozen additional interviews; these have been collected and archived as the Mill Worker Oral History Project. I draw on both collections in this essay; quotations are cited by the page number of interview transcripts.

3 Roland Gosselin, personal communication. Gosselin was a member of the Millworker Advisory Committee, a group of retired elders with whom my students and I vetted our research and interpretive thinking.

4 Rachel Desgrosseilliers was particularly emphatic about the importance of survivance in our planning conversations. Research by undergraduate Nate Purinton was particularly important in mapping key practices and institutions of Francophone solidarity.

5 It should be noted the Lionel Audet was interviewed both by oral historian Andrea L'Hommedieu for the Mill Worker Oral History collection and by Bates students Thomas Burian and Eliza Reed as part of the Student Mill Worker Oral History collection. The first focused especially on Audet's experience in the mills; the student interview engaged more personal issues of childhood, religion, and military service.