Organized in 2009, Artists in Context (AIC) is a flexible organizational framework that assembles artists and other creative thinkers across disciplines to conceptualize new ways of representing and acting upon the critical issues of our time. AIC has identified eight of these issues—Nature, Health, Consumption, Justice, Learning, Belief, Nation, and Shelter—and supports both New England-based and national artists whose existing work and ideas for future projects are centered on these themes.

Through the Artists' Prospectus for the Nation, a multimedia compendium of artists' projects that exemplify the highest standard of contextual contemporary art practice, AIC helps to define the role of artists as researchers, collaborators, public intellectuals, and catalysts for social advancement. Participating artists range from the most established, such as the internationally renowned Alfredo Jaar, to those in early stages of their career, such as these artists who are interviewed here: Sara Hendren, Cathy McLaurin, and Nadia Afghani and Unum Babar.In the fall of 2012, these students collaborated with Jaar who, with support from AIC in partnership with Harvard University's Cultural Agents Initiative, taught a Public Interventions course.

Setting the Stage and Realizing the Vision

While the impulse to make art in the service of promoting a better world or moral good is centuries old, in this era of late-stage capitalism, artists increasingly trade the platform of the expert art world for the real world because the times demand it. Today, growing numbers of artists leave the silo of art and link their practice to the broader culture, which is in desperate need of their creative re-visioning and finely honed skills. Our political process has been reduced to theatrical antagonism; corporations have assumed individual rights; our reliance on science and technology continues to distance us from that which gives us life; and bioengineering threatens to erase the idiosyncrasies that make us who we are.

Over thirty years ago, Roman Verostko, former professor at the Minneapolis College of Art and Design and early pioneer of algorithmic art, anticipated the socially integrative practices of artists that we witness today. In a paper presented by Verostko, "A Futures Outlook on the Roles of Artists and Designers," at the First Global Conference on the Future, held in Toronto, Ontario, in July 1980, he addressed the prospective role some artists play in shaping the consciousness of an era. His focus was a post-industrial society where the emphasis on the production and consumption of goods and the exploitation of natural resources to achieve that end must be replaced with a greater sensitivity and understanding of the inter-relation between human activity and all other matter.

Verostko wrote,

I think we will see the artist less and less concerned with . . . forms, as it were, of "my experience," "my concept." These will be replaced more and more with forms pointing towards the quality of our experience of the world. Or we may have forms which focus our attention on alternative ways of designing and arranging human experience for the greater realization of self and community.Given these value shifts, we may experience a new kind of artist more integrated regionally in our everyday world, our nature centers, our market place, and our industry. And the artist in such a context and engaged this way may not have a name. In such an event, a strange thing shall have happened; the artist will be 'Every Person.' Art and life will be one. (Verostko 1980)

AIC takes up Verostko's vision in furthering art that places foremost value on context and common purpose. While fitting into a historical continuum of artists engaged with the social sphere, the contemporary manifestation of social practice represents a renewed commitment and new approaches to art as a vehicle of functionality and utility, the creation of new knowledge, and systemic transformation.

Connected and Consequential

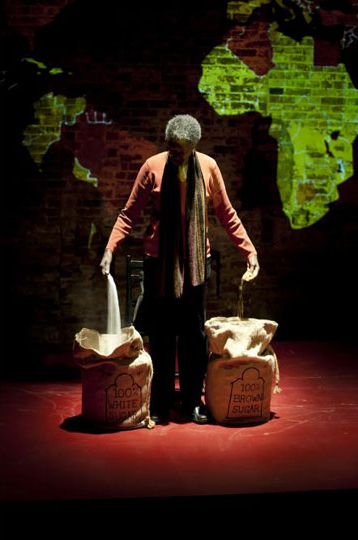

To highlight and encourage this type of contemporary art practice, AIC created its Connected and Consequential Program (2010–2013), which offered opportunities for artists to interact, think, and collaborate with creative minds from academia, the private and public sectors, and local communities. AIC organized four Connected and Consequential conferences: in Boston, MA; Providence, RI; Portland, ME; and Northampton, MA. Each convening offered case studies of social practice from that particular region and included a keynote speaker, discursive sessions, and professional artists training sessions focused on research methods, collaboration, new forms of organizing and producing, theory, and new technologies. For example, in Boston, Robbie McCauley's SUGAR was one of the featured projects. Robbie, who is herself diabetic, is concerned about health disparities reflected in the social, historical, and global scope of diabetes. She created the piece by combining fragments of her personal experience with the stories of others affected by diabetes, which the artist collected through the creative tool of story circles. A story circle is a simple form wherein people sit in a circle and listen to stories based on their interests and concerns. At the start, the circles require a facilitator, who frames the gathering. After listening to all who choose to talk, the facilitator then gives cues for dialogue—for people to comment and exchange with one another from what they have heard. The process facilitates connection, laughter, performance modes in telling stories, heightened understanding, and compassion among the participants.

AIC arranged several multi-session story circles for Robbie at community health centers, including the Mattapan Community Health Center and Hearth, an organization that provides shelter for formerly homeless elders. AIC also connected Robbie with medical and public health professionals who acted as advisors and collaborators and with whom she has sustained a long-term working relationship.

Through the story circle process and her engagement with medical experts, McCauley constructed the SUGAR project to represent many different perspectives on diabetes, and therefore created a more textured understanding of the disease. Often buried in statistical information that can render us passive are the personal, complex narratives that connect us on a visceral level and give issues greater meaning.

At the Providence convening, AIC presented Ellen Driscoll's Distant Mirrors, which focuses on the implications of society's oil and plastic production. The project consists of a floating public artwork made from recycled plastic and a content-rich website dedicated to her research on oil and plastic production/consumption. To realize the work, Ellen worked in collaboration with the Rhode Island Recovery Corporation and landscape architect Ponnapa Prakkamakul.

As a report to the national field on this regional work, AIC organized a conference in 2013, Artists and the Future, for funders and knowledge leaders to learn more about contemporary contextual practices and the value being created at the intersection of art and medicine, art and technology, art and justice, and art and environmental health. The national conference consisted of case studies of artists working with other experts on new approaches and a panel on alternative methods of cultural production.

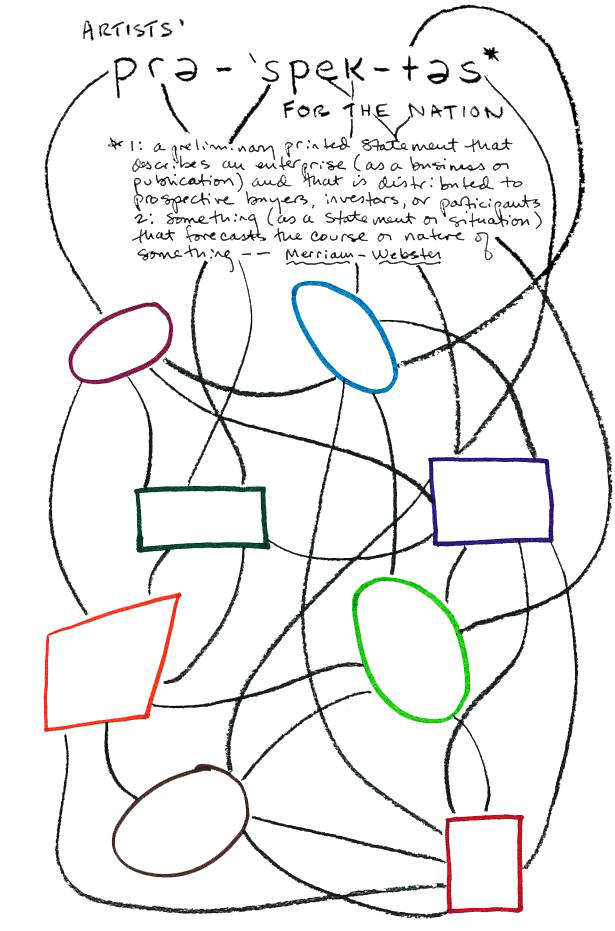

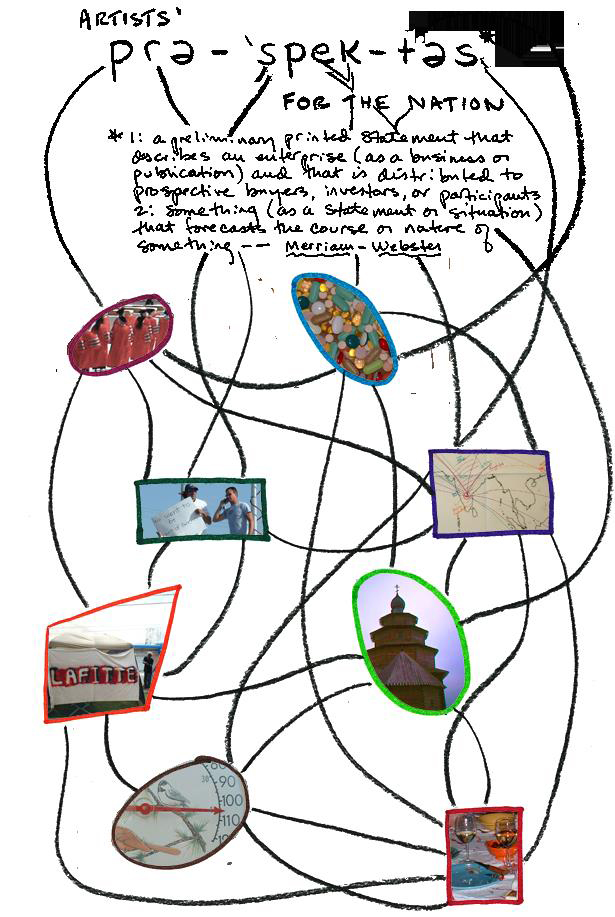

The Artists' Prospectus for the Nation

AIC's other main project, the Artists' Prospectus for the Nation, is a bold attempt to capture this remarkable work and disseminate it broadly. The mission of the Prospectus is to be a catalyst of change, provide a dynamic platform for artists and designers to engage people and communities on important issues of our time, and offer ways to restore a sense of agency around those issues. It is a curated group of artists whose collaborative and transdisciplinary research, writing, and projects offer arguments, models, and solutions to redress and improve contemporary, real world challenges. It highlights artists who seek to compose rather than critique, to be integral forces within society rather than observers or critics.

Late in the twentieth century and into the early twenty-first century, art has been deeply intertwined with global market systems. Art is measured by its economic power, the desire for its consumption, and the return on investment it provides. Curators, gallerists, and others involved in the art market system fiercely protect their institutional purview to adjudicate the value of art.

AIC created the Artists' Prospectus for the Nation to challenge the notion that art created outside the dominant art world is not art, and to issue a call for a critical discourse that could and should frame social practice in art. We have assembled projects whose use and aesthetic gesture are intermixed to create examples of cross-sector research and integrative thinking. The projects reflect that elusive middle space, or heated core, where aesthetic form and purposeful content converge powerfully to change the way we perceive, think, and act.

Contemporary artists who seek systemic transformation traverse multiple disciplines, fields, and sectors and co-mingle their form of knowledge with other forms of knowledge, experience, and methodologies. Their practice reflects a vital reconciliation of reason and intuition in the transmission of knowledge.

Grant Kester, in his introduction to Gallery as Community: Art, Education, Politics contends that "The crucial issue . . . for all of us moving forward into the future, will be how to reconcile the forms of knowledge and affect generated by autonomous critique with the need to create new solidarities and new collaborative relationships" (Steedman 2012, 16). He is, of course, suggesting that we expand our notion of art and artist beyond the museum and gallery in order to produce the change that a sustainable future demands. We must see artists anew, as collaborators, researchers, and facilitators of change. Similarly, we must see artful thinking as a valuable form of knowledge that when integrated with other forms of knowledge allows us to see, think, and act more holistically, justly, and sustainably.

The Advent of Sociological Art: Fred Forest

One of the most influential artists to challenge the parameters of the dominant art world is Fred Forest. Born in 1933 in French Algeria, Forest became intrigued with new media technologies and was influenced by the cultural unrest of 1968. He was drawn to the avant garde tradition that challenged the boundary between art and everyday life, and was influenced by the theoretical underpinnings of the French Situationists, Marshall McLuhan's philosophy of communication (McLuhan, 2008), and Umberto Eco's idea of the open work (Eco, 1989)—conceptual practices in which an art work has no definitive end point.

Beginning in the late 1960s, Forest aspired to a utopian form of social practice operating as art. As early as 1967, Forest organized a series of participatory and community-based art activities that laid the foundations for the Sociological Art movement to follow.

In their "Manifest 1 of the Sociological Art" (published in Le Monde in October 1974), Fred Forest, Hervé Fischer, and Jean-Paul Thenot articulated the principles of a collective structure for art and artists primarily concerned with the fundamental theme of sociological research and action:

The collective of sociological art, by its artistic practice, has the tendency to put art in question, to put in evidence the sociological facts and to "visualize" the elaboration of a sociological theory of art. The collective of sociological art fundamentally resorts to the theory and methods of social sciences. . . . It puts the art in relation with its sociological context . . . and draws attention to . . . [a] new theme in the history of art, and that implies also a new practice. (Fischer, Forest, and Thenot 1974)Forest's initial sociological walk took place in Sao Paulo, Brazil, in the context of the military regime. The context was key to Fred's interest in animating public space (Bianco 2011).

Through advertisements placed in the national press, the artist recruits participants in a "sociological promenade" through the working class district of Brooklyn on the outskirts of the city, during the course of which he comments on aspects of the urban environment and interviews merchants and residents about the social conditions in which they live. (Forest 1973)

A re-animation of the walk took place in Brooklyn, NY in 2011, during a six-month residency made possible by Residency Unlimited.

The quest to create a space for critical questioning, to stimulate "the interrogative conscience of all" (Fisher, Forest, and Thé not 1977) is the impulse that defines most serious art. Presently, there is an urgent need to open up the tightly controlled fabric of contemporary society, motivated by capital markets and self-interest, as reflected in the popular movement Occupy Wall Street. Artists today seek to create similar platforms, such as online interactive storytelling sites, environmental health clinics, and competitive games, in order to provide the space for citizens to consider the complexity of issues that we face, to re-consider standing societal conventions and attitudes, to re-engage as participants, and to perceive and ideally take a better path forward.

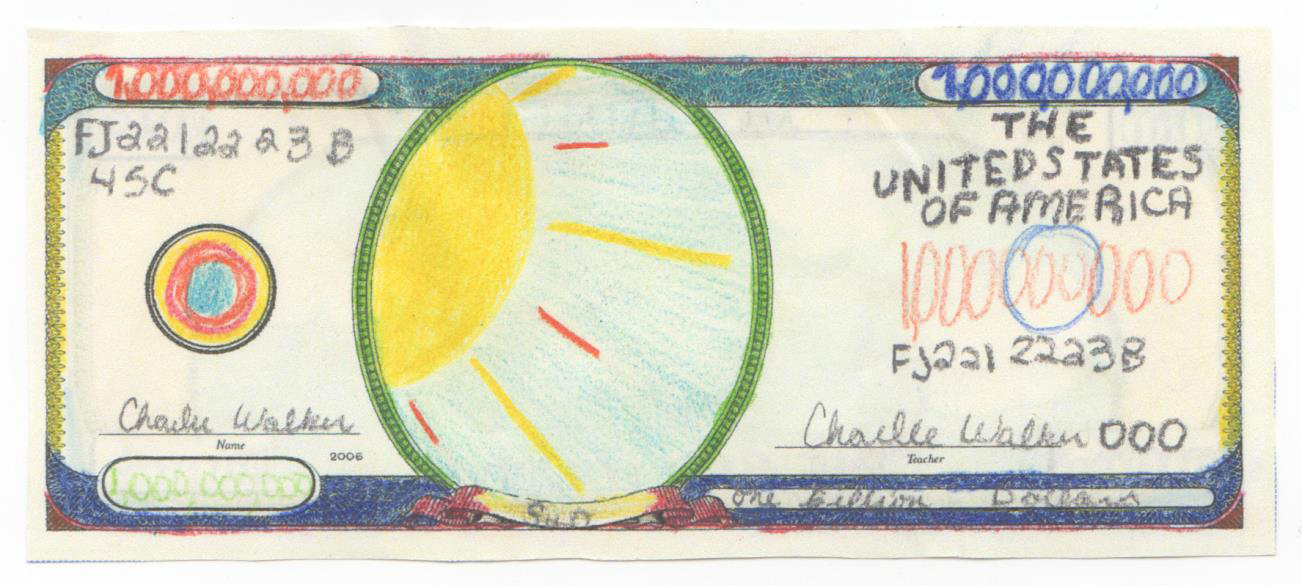

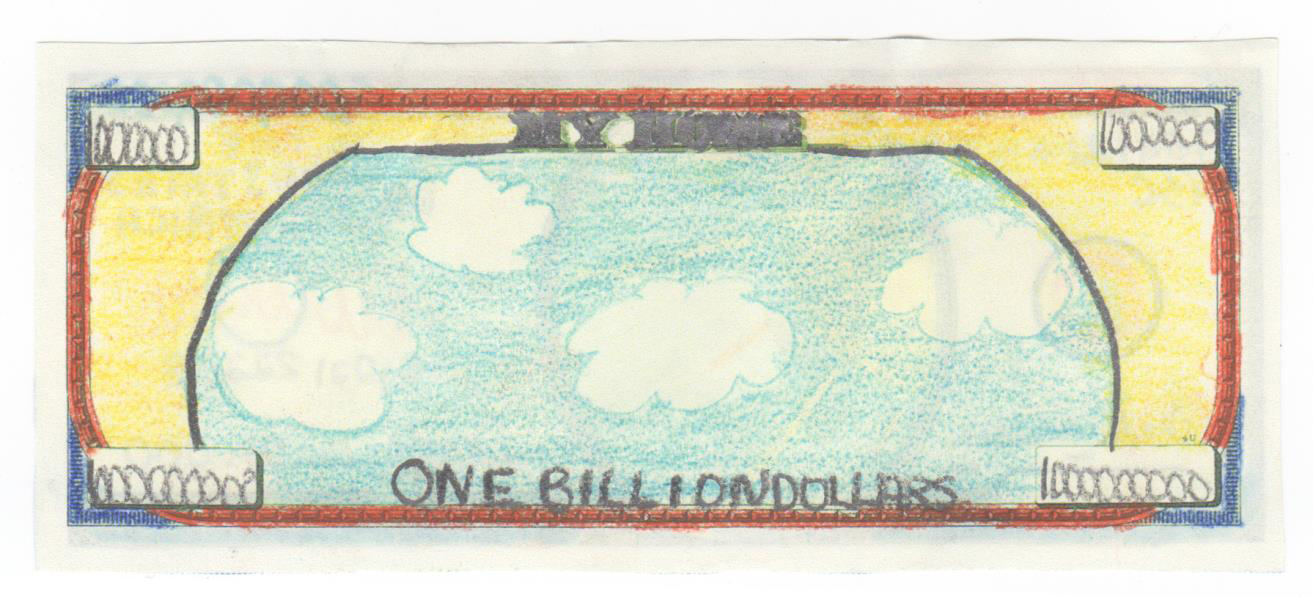

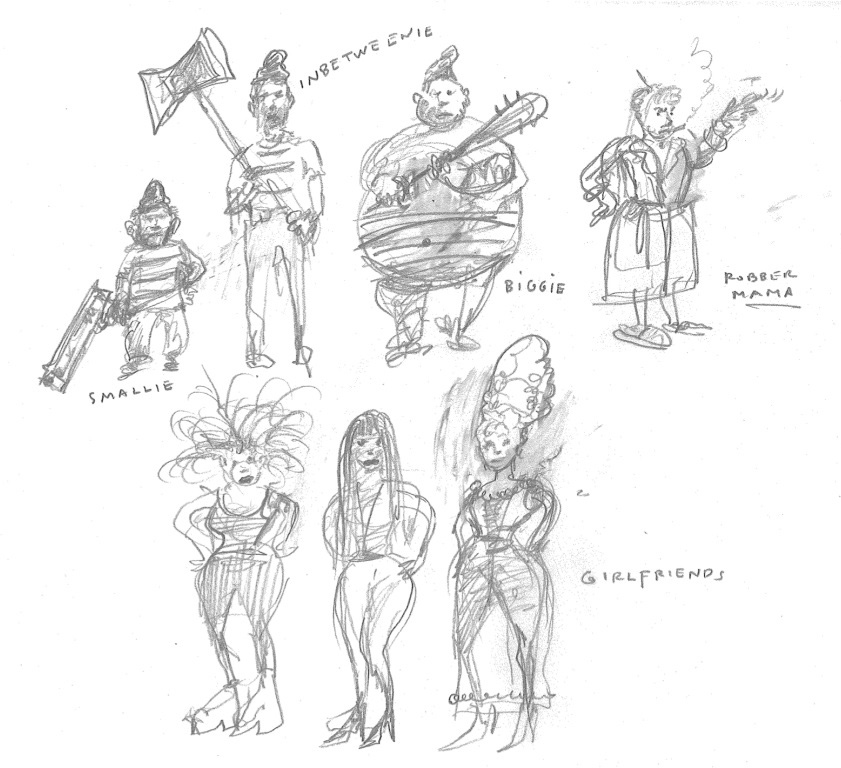

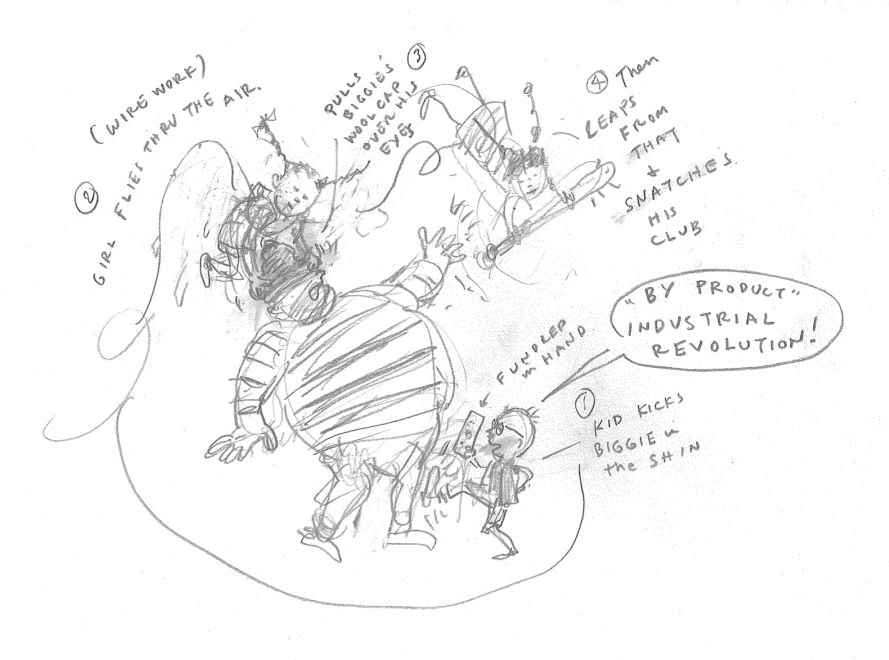

An example of how these ideas take form is Mel Chin's collaborative project, Operation Paydirt (2006–present), which strives to make people aware of the dangers of childhood lead poisoning. Focused initially on a section of New Orleans, where the problem of lead contamination preceded the notorious devastation of Hurricane Katrina, Mel is collaborating with scientists, environmental protection agency officials, politicians, community and workforce development officials, landscape architects, municipal and national health departments, and others to develop a national campaign to protect children against lead contamination. In the process, Mel and his collaborators seek to engage the entire nation in the project by creating a vehicle for awareness and action. People across the country are drawing "fundred" dollar bills while learning about the causes and effects of lead. Fundreds are original, hand-drawn interpretations of US $100 bills. The goal is to collect millions of these unique artworks and present them to Congress in a symbolic act to represent the concern of the American people and their request for an exchange of actual funding and innovative solutions to the national crisis of childhood lead poisoning. The Prospectus Project related to Operation Paydirt is Neurotoxic Element, a hip hop music video that is one element in a portfolio of strategies to raise awareness, educate, and engage stakeholders.

Perhaps the most significant point of contact between Fred Forest and contemporary Prospectus artists is the belief that "art is a discipline with the specific aim of creating a hybrid of all forms of knowledge, an original conceptual tool that allows us to explore our lived existence, while all the while reconciling body and mind, the concrete and the abstract" (Romberg 2006).

Prospectus artist Natalie Jeremijenko's Environmental Health Clinic offers an example of the transdisciplinary form of knowledge to which Romberg refers. The environmental health clinic is a conceptual tool composed of multiple bodies of knowledge—art, design, biochemistry, physics, neuroscience, and precision engineering—that encourages us to re-imagine our relationship to nature. No single body of knowledge or discipline is privileged over another. All work together, in energetic combination, to create a platform where the concrete and abstract, mind and body, visible and invisible, converge to engage us fully in our experience of the depth and complexity of our interconnections with nonhumans.

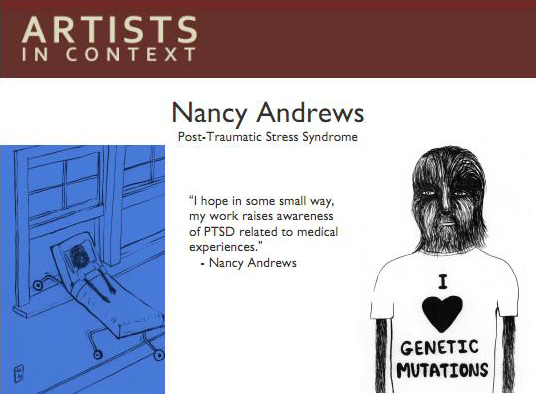

By inserting their artful ways of knowing and producing into many different fields, such as physical and social science, medicine, community health, autism, environment, technology, politics, and immigration, Prospectus artists broaden the approach to the issues beyond that which is visible, concrete, and provable through fact. Artists bring a uniquely embodied set of symbolic languages and performative strategies to these issues. Nancy Andrews' Delirious drawings, for example, offer a complex, ambiguous, and ethical portrayal of a patient in an Intensive Care Unit (ICU). Doctors at Brigham and Women's Hospital, who saw the drawings and films Andrews made about her experience in the ICU, volunteered that the visual work had given them a new and different perspective on delirium, and had made visible to them what had remained invisible. The work revealed what science could not: a personal, visceral, passionate, and visual representation of a chaotic mind in a delirious state. Dr. Gerald Weinhouse, Associate Physician, Brigham and Women's Hospital Assistant Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School, has launched a new research study on the effects of music on ICU patients, inspired, in part, by what he learned from Andrews' visual work. Andrews was also asked to be a consultant on a medical research study at the University of Nebraska School of Nursing. The study focuses on a set of evidence-based practices, the ABCDE bundle of practices (Balas et al. 2012), that performed collectively can improve outcomes for ICU patients.

Kelly Dobson's Womb Room offers an example of how artists are working beyond a single discipline to create new forms for the future. Dobson moves fluidly between the realms of digital media, machine design, public performance, and social systems. In addition to her extradisciplinary investigations, Kelly collaborates with other experts from other fields. She is creating a neonatal project in collaboration with Women and Infants Hospital of Rhode Island, having formed relationships with several of its Neonatal Intensive Care Unit medical personnel. The project addresses the human needs that are present in the neonatal environment—critical needs that are overshadowed by the clinical imperatives of contemporary medicine.

Fred Forest wrote in 1985, "Where are the frontiers of art situated? . . . There is no frontier. Art is an attitude—a way of relating to something, rather than a thing in itself" (Forest 1985). This is my answer to the question of whether art that is purposeful, with intended outcomes, is still art. The artfulness of Kelly's Womb Room is not the object itself; rather, the artist's attitude toward health and well-being as a constellation of biological, social, and affective factors carries much more impact than the resolution it provides.

Building A Frame

Contemporary art practices engaged in expanded social, political, environmental, health, and other cultural issues deserve "a dialogue of critique," according to Gavin Kroeber, a participant in the Boston Connected and Consequential conference. The field of social practice art—also known as new genre public art, dialogical art, relational art, and hybrid art—is a complex domain of activity. There is no consensus about the critical discourse that could or should frame it.

Developing the Artists' Prospectus for the Nation as a collection of curated projects was envisioned as one early step in the process of building a frame around contemporary art practices that are connected to the ideas of use, utility, and usefulness. AIC selected the title The Artists' Prospectus for the Nation to indicate that artists are creating, in collaboration with other thinkers from a variety of fields, useable, implementable proposals to help society think and act in new ways.

Through the lens of the Prospectus, the public can learn more about the role artists play as researchers, collaborative thinkers, shape-shifters, and bridge-builders in society, who seek to engage them as participants in re-thinking existing narratives important to their lives.

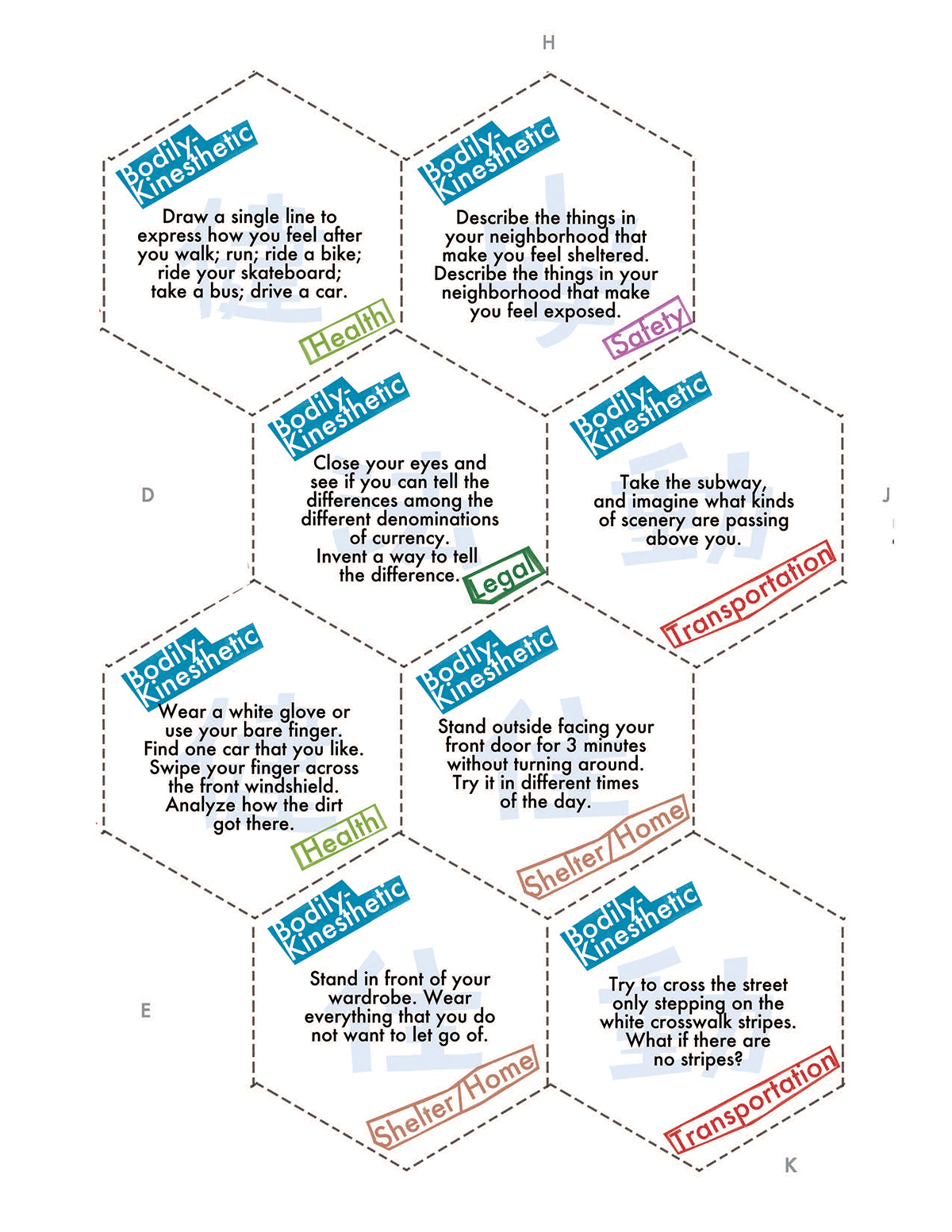

The Prospectus was originally conceived as a tri-part project: a website, a print publication, and a box containing multiples of objects related to the projects documented in the Prospectus, such as small paintings on recycled plastic from Ellen Driscoll's project FastForwardFossil; a placemat designed for the project Sugar; the Process of Elimination Card Game; an AgBag kit, designed as a protocol of the Environmental Health Clinic; Creative Determinant of Health cards and poster; and a graphic short story from the project Loupette.

The idea of the box comes from Marcel Duchamps' Boite-en-Valise (Box in a Suitcase) (1934–1941). Duchamp's questioning of the sacred nature of rare and unique works of art, evidenced by his "most significant works cleverly arranged inside each little box like a traveling salesman's wares" (Taylor 2012), informs AIC's impulse to represent art that is outside the context of expert culture and that flourishes in a public, amateur, and useful way.

The vision is to create a deluxe edition of boxes and present them to public policy and knowledge leaders, in order to generate a re-thinking of the critical issues of our time and public policy in this country. At present, the Prospectus exists as a website where people are able to download a selection of the objects.

Both Duchamp's oite en ValiseB and the Artists Prospectus for the Nation seek to challenge conventional thought about artistic processes and the rarified boundary of art. Each is filled with individual works of art, but the framing device of the box and the prospectus are perhaps the most creative acts of all.

Platforms for Change

Re-framing our perception and reception of art underlies the intention of dadaism, the sociological art movement, and today's artists who graft their practice creatively together with other forms of knowledge. The pursuit of collaboration with thinkers and practitioners outside of the art discipline is essential to achieve a systemic engagement with society.

Brian Holmes describes the impulse of artists to reach beyond their own discipline:

At work here is a new tropism and a new sort of reflexivity, involving artists as well as theorists and activists in a passage beyond the limits traditionally assigned to their practice. The word tropism conveys the desire or need to turn towards something else, towards an exterior field of discipline; while the notion of reflexivity now indicates a critical return to the departure point, an attempt to transform the initial discipline, to end its isolation, to open up new possibilities of expression. This back and forth movement, or rather, this transformative spiral, is the operative principle of what I will be calling extradisciplinary investigations. (Holmes, 2007)

Claire Pentecost's essay on the public amateur highlights the increasingly integrative role artists occupy in society and the opportunity they seek to engage other expert cultures:

The artist becomes a person who consents to learn in public. This person takes the initiative to question something in the province of another discipline, acquire knowledge through unofficial means, and assume the authority to offer interpretations of that knowledge, especially in regard to decisions that affect our lives. The point is not to replace specialists, but to enhance specialized knowledge with considerations that specialties are not designed to accommodate. . . .

. . . Our culture asks too high a price of society when it insists on narrow professional specialization. Conforming to this demand divides our intellect from our emotions, our imagination from our efforts, our pleasure from our worth, our verbal and analytic capacity from other creative talents, and our ethics from our daily lives. (Pentecost 2009, 2)

Artists included in AIC's Artists' Prospectus for the Nation are not concerned with holding their expertise above other expertise. There is an ethic of shared experience, knowledge, and effects embedded in the work. They look for ideas and meaning beyond their own imaginations and chart a map that spans across ideas, physical places, and disciplinary affiliations. They engage the expertise they need or introduce themselves to new forms of knowledge or practice (engineering, permaculture, biomedical research) to devise, implement, and insinuate new approaches to the critical issues of our time.

We are witnessing a further evolution in art that addresses the disconnection in our society. It heralds the emergence of platforms that offer people the opportunity to unpack complexity, make sense of it, and have an effect on issues that seem intractable. These platforms also reinforce the fact that we are encased in one giant feedback loop; that we are all inextricably linked to each other, to things, and to nature; and that every action we take has a consequence. These platforms entangle different bodies of knowledge and different ways of knowing a subject and therefore offer a more holistic and contextualized understanding of an idea, issue, or challenge. We are more richly informed if we combine the scientific and technical side of a subject with its intuitive and narrative interpretation. If we add a third component, the component of power, these platforms represent a new architecture for change in society. Artful ways of knowing and practicing, when integrated equitably into society's system of knowledge production, have the potential to generate new questions, new priorities, new attitudes and behaviors that will help us to define, build, and inhabit a more responsible future.

Works Cited

Balas, Michele C., Eduard E. Vasilevskis, William J. Burke, Leanne Boehm, Brenda T. Pun, Keith M. Olsen, Gregory J. Peitz, and E. Wesley Ely. 2012. "Critical Care Nurses' Role in Implementing the 'ABCDE Bundle' into Practice." http://www.aacn.org/wd/Cetests/media/C1223.pdf.

Bianco, Mike. 2011. "From Brooklin (1973) to Brooklyn (2011): An Interview with Curator Ruth Erickson." http://temporaryartreview.com/from-brooklin-1973-to-brooklyn-2011-an-interview-with-curator-ruth-erickson/.

Eco, Umberto. 1989. The Open Work. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Fischer, Hervé, Fred Forest, and Jean-Paul Thenot. 1974. "Manifest 1 of the Sociological Art," Journal Le Monde, October 10.

———. 1977. "Manifest IV of the Sociological Art," Journal Le Monde, February.

Forest, Fred. 1973. "Sociological Promenade in Brooklin." Web Net Museum. http://www.webnetmuseum.org/html/en/expo-retr-fredforest/actions/09_bis_en.htm#text/.

———. 1985. "For an Aesthetics of Communication." Plus Minus Zero.

Grynsztejn, Madeleine. 2013. "Realities Represented." Aesthetica, 52–53.

Holmes, Brian. 2007. "Extradisciplinary Investigations: Toward a New Critique of Institutions." European Institute for Progressive Cultural Policies.

Latour, Bruno, and Peter Weibel, eds. 2005. Making Things Public: Atmospheres of Democracy. Cambridge: ZKM and MIT Press.

McLuhan, Eric. 2008. "Marshall McLuhan's Theory of Communication: The Yegg." Global Media Journal, 1 (1): 25–43.

Pentecost, Claire. 2009. "Beyond Face." http://publicamateur.wordpress.com/2009/01/18/beyond-face/#more-34.

Romberg, Osvaldo. "Art and Society: The Work of Fred Forest." 2006. Exhibition catalogue essay for Art and Society: The Work of Fred Forest at the Slought Foundation, Philadelphia, PA.

Steedman, Marijke, ed. 2012. Gallery as Community: Art, Education and Politics. London: Whitechapel Gallery.

Taylor, Michael. 2012. "Marcel Duchamp, The Box in a Valise. " Lecture at the Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire.

Verostko, Roman. 1980. "A Futures Outlook on the Role of Artists and Designers: Art as if People Mattered." FUTURICS 4: 269–278.