An integral part of the Spanish curriculum at Occidental College, Span 211 Advanced Spanish for Native Speakers, is a course designed for native Spanish-speakers with different degrees of formal training in the language.1 When the course was created in 1994, it was very common to have several students with no formal knowledge of the Spanish language so the instructor had to focus on teaching the rules of spelling and grammar. However, in recent years the majority of our bilingual students have already taken several Spanish classes, including AP language and literature, entering college with a more solid understanding of the language. Many have also received informal instruction, thanks to their families and communities. Most students are ready to undertake more challenging projects while continuing to develop their communication skills in Spanish. Furthermore, current studies in Spanish heritage language pedagogy have identified the benefits of engaging with the community and including more community-based activities in the instruction of these courses.2

We found excellent opportunities to engage in meaningful collaborations with nearby schools, literacy centers, hospitals, and law agencies serving large Spanish-speaking populations. Since all of these organizations shared an urgent need to have information available in Spanish, we decided to devote one section of the class to the translation of documents for the community. In this context, in 2006, we accepted a request by Sundance Vista, a public housing development in Los Angeles, to translate their governance bylaws. Since it was our first attempt at teaching and doing translation, we made many mistakes. We chose a document that was too long and difficult. We were ignorant of the legal and social context and did not know who would benefit from this translation. We failed to assign the work in an effective way, asking each student to work independently, preventing collaboration and teamwork. The preliminary results were not very positive. We were frustrated by the amount of revision and the responsibility associated with translating a binding document. Gradually the students became uninterested in this assignment and the whole project came to a halt.

We needed a new source of motivation. After consultation with the Center for Community Based Learning (CCBL), we invited a group of people associated with Sundance Vista to our class to explain the significance of having those documents translated. The Spanish-speaking residents told us how inhibited they felt because of the language and culture barriers they faced. Lack of information in their native tongue prevented them from understanding the governance bylaws. They did not know how to choose their representatives for the executive board or how to submit a petition or share a concern. With their candid accounts, the people of Sundance Vista reenergized us, giving purpose and meaning to our task. Because of that collaboration, we were able to complete the translation and enjoy the satisfaction of having done something useful both for the community and ourselves.

For various reasons we did not integrate a translation component into the course until fall 2010, at which time we had a more realistic appreciation of what a good translation for the community entailed. We knew that it required real collaboration among the primary stakeholders—the instructor, the college, the students, and the community partner—to create larger meaning. Our goal was to move from a transactional relationship, addressing an immediate need from the community—i.e., the translation of a specific document—to a long-lasting partnership that could change and evolve to benefit all parties.3 Three years later, what started as a minor component of the class has become a multi-year, cross-sector, cross-disciplinary collaboration. By joining with different departments and centers at the college, we have increased and consolidated our community involvement in health care, legal services, education, and the arts. In conjunction with our community partners, we have developed new forms of engagement such as internships and research, providing our students with meaningful opportunities for linguistic, pre-professional, and civic development. In fact, this paper is in part the result of a collaborative research project that we conducted with two of our community partners, the Public Counsel Law Center and Cedars-Sinai Hospital, along with the students who participated in the class and/or the internship.

Collaboration within the College

We always work in cooperation with our Center for Community Based Learning (CCBL). We have collaborated with them to create meaningful projects, identify the appropriate community partners, and establish good communication channels with the selected organizations to enable long-lasting relationships. We work together with the center's director, Celestina Castillo, and student facilitators in every stage of the process: from the conceptualization of the assignment to the end of semester debriefing and assessment; from punctual assistance with logistics and funds to ongoing intellectual and personal support. Their knowledge, diligence, and guidance are essential pillars of our community involvement. Thanks to their facilitation, we have developed partnerships with seven community organizations: Centro Latino for Literacy, CALS Charter Middle School, Public Counsel Law Center, Legal Aid Foundation of Los Angeles, Disability Rights Legal Center, Cedars-Sinai Hospital, and the Autry National Center of the American West and we have done translations for them throughout the years.

Because of CCBL, we have also partnered with other faculty members at Occidental. For instance, in Fall 2010, Prof. Sharla Fett in the history department was compiling a brief history of health care reform in the United States at the request of a group of promotoras de salud of Los Angeles. These promotoras are community members who serve as liaisons between their community and health, human, and social service organizations providing information and resources. Prof. Fett, along with the students in her HIST 277 Cross-Cultural Perspectives on Women and Community Health class, created a comprehensive document for the promotoras to present at their annual conference. Because the promotoras mostly work with Spanish-speaking communities, they also wanted a Spanish version of the document. Therefore, we teamed up with the history class to produce the Spanish translation. In the process, we expanded the scope of our class, increasing our community involvement and partaking in the production of knowledge within the parameters of another discipline. It was a very rewarding experience for us, and we were happy to learn that 900 copies of the document, 700 in Spanish and 200 in English, were distributed at the promotoras' conference.

In Fall 2012, we initiated a partnership with the Autry National Center Museum to translate the text of a virtual exhibit of California paintings (http://theautry.org/collections/fenyes-biography) into Spanish as a spinoff of an existing venture between the Autry National Center and Occidental College. As these examples show, collaborating with colleagues from different departments and with the Center for Community Based Learning has been essential to establishing mutually beneficial and well-defined relationships with the community, even transcending disciplinary boundaries.

Keeping Students at the Center of the Learning Experience

While engaging in these cross-disciplinary and community partnerships, we have had to keep in mind the students' interests and expertise in order to avoid indifference and frustration. Our students have responded especially well to documents related to education, immigration, and health care. Many of them are considering careers in those fields, and look forward to learning more about specific issues. Short documents—forms, letters, flyers, syllabi—are most suitable to our translation abilities and easiest to fit in our calendar. The students learn basic translation techniques and become familiar with printed and online resources, such as dictionaries and glossaries, before tackling the translation of the first document.

The same spirit of collaboration that permeates the community engagement project pervades the process of translation amongst students in the class. Groups of two or three students are assigned one document and are jointly responsible for preliminary drafts and revisions. Since the students speak different regional varieties of Spanish, one of the main challenges that they encounter is reaching consensus on the appropriate words to use. By negotiating meaning, the students become more aware of language variation in the Spanish-speaking world and increase their sensitivity to different dialects.4 From a linguistic point of view, the translations contribute to the enrichment of the students' communication abilities in Spanish, especially in areas such as grammatical competence, vocabulary acquisition, and writing accuracy. From a pre-professional perspective, the translations provide the students with the acquisition of valuable techniques and knowledge that they can apply in their future careers. As one student articulated in the end of semester survey, "having translating skills, group work experience, and responsibility can be applied to different [professional] fields."

Making Room for the Community Through Action and Reflection

Including the community in our learning endeavors has added a public dimension to our class. Even though many of our interactions take place in the virtual realm, exchanging documents and information electronically, our community-oriented translations have helped us transcend the spatial limits of the classroom and interact with the world outside. Translating for different organizations opens our minds both to the specific problems addressed in the documents and to larger issues regarding social inequality and disparities in the access to information and services. Through our collaboration with law centers, schools, and hospitals we have learned about the struggles of many Spanish-speakers who are unable to exercise their labor, educational, or civil rights because of the lack of documents available to them in Spanish. Even the community organizations trying to assist them have to endure this shortage of relevant materials as well as the scarcity of bilingual personnel.

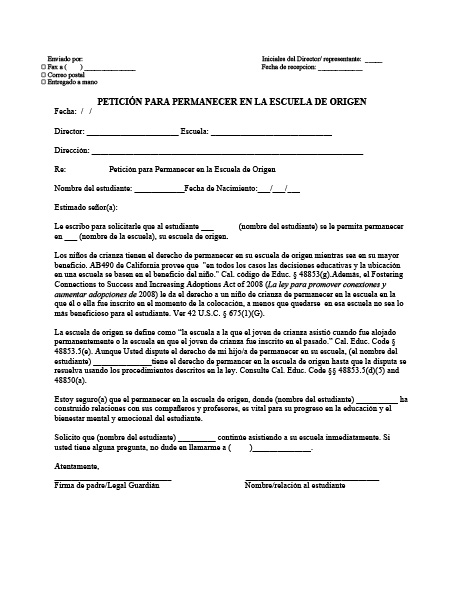

For instance, the representatives of the Public Counsel Children's Rights Project, who handle all aspects of educational rights advocacy, explained to us that "according to the California Education Code many of these documents are supposed to be available in Spanish, but in reality they are not."5 To alleviate this situation, we choose documents that require immediate translation and that are also suitable for my students in terms of length and difficulty. The staff at the Public Counsel provide us with the necessary background information, explaining the legal and social context of the issue at hand, and sharing essential tools such as glossaries and pamphlets, and, more importantly, their professional expertise. We are especially grateful to Ben Conway and Lisa Higuera who are available to us throughout the semester, answering our many questions about specific terms and concepts and putting their knowledge and bilingual skills at our disposal.

The forms that we translate offer facts and explanations to pressing questions, including: What are your rights if your child is about to be expelled from school? Who qualifies for financial aid benefits to go to college? These translations are our material contribution in the process of obtaining social justice. By making information and services accessible to the Spanish-speaking communities we are facilitating their access to basic democratic and human rights that other citizens have.6 As one student declared: "I underestimated what I can really do . . . my language abilities can be used to help others, in this case by translating valuable information for people to have access to." Along those lines, the majority of the students expressed a new perception of their role in the community. Their responses to the reflective section of the final exam consistently establish a correlation between their linguistic progress and their commitment to the betterment of the community both at a personal and a professional level, recognizing their translation skills as powerful tools. We believe that this new awareness of the needs of the community and the realization of their own ability to meet those needs set the students on the right path to become more than just helpers.

Community Members as Mentors: Class Visits and Internship

In another effort to help the students envision different forms of collaboration with the community, as well as foresee their own potential role in those partnerships, we added a mentoring component to the class. To continue to bridge the gap between the public and private spheres, and since most of the students in Spanish 211 are the first in their families to go to college, every semester we have invited several Latino alumni working in the community to share their academic and professional trajectories with us and to demonstrate how being bilingual and able to translate has helped them in their careers. Educators, doctors, therapists, graduate students, and artists have visited our class, providing valuable insights about the professional world and instilling pride and confidence in our students. They have also conveyed the challenges and satisfactions of working with Latino communities in their role as mediators between institutions and people.

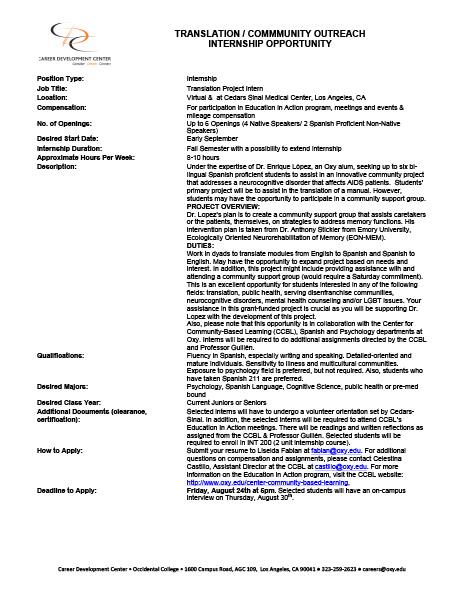

Dr. López's account was particularly compelling. As a neuropsychologist at Cedars-Sinai Hospital in Los Angeles, Dr. López works with HIV positive patients affected by neurocognitive disorders that result in memory loss. The inability to remember important things, such as taking their medications on time, can be extremely detrimental as they need to follow their treatment plan closely in order to maintain quality of life. To help both the patients and their caretakers, Dr. López created a community support group to assist them in developing strategies to address memory functions. Frequently working with Latino populations, he faced the challenge of making those strategies transferable to different languages and cultures. Though bilingual in English and Spanish, Dr. López explained how exhausting it is translating on the spot from the written materials in English for the Spanish speakers. The students were moved by his talk and asked if there was any way to help. After meetings with Occidental faculty and administrators, as well as Dr. Lopez and his team, we created a unique internship opportunity.

During the planning stages, we established that the internship had to be more than a practicum on translation, but also a chance both to explore the professional world and to become more engaged citizens. To achieve those goals, the student interns would be required to do readings and reflection, under the guidance of Celestina Castillo, the director of the Center for Community Based Learning, in addition to their translation work and meetings with Dr. López. Since there was no precedent at Occidental of an internship like this, we had to create a structure. We want to acknowledge the contribution of Liselda Fabian, Internship coordinator at the Career Development Center, who educated all of us about different types of internships, credits, and requirements, and collaborated to create the project description, the calendar of activities, and the intern selection process. Dr. López's feedback and support were essential to our progress. We also consulted with the Psychology Department to identify reading materials for the interns. Given the enthusiasm and hard work of all the people involved, we launched a pilot version of this internship less than three weeks after our initial meeting. Four students from our Spanish for Native Speakers class, who had demonstrated maturity and a desire to serve disenfranchised communities, were selected to participate. The trial experiment worked so well that we continued the internship, expanding its scope and increasing the number of students.

We are about to enter our fourth semester and we could not be happier about the results. The interns are finishing the translation into Spanish of Dr. Anthony Stickler's manual, Ecologically Oriented Neurorehabilitation of Memory, which Dr. López uses in his community program. Having this manual translated into Spanish will be beneficial to health care professionals who work with Spanish-speaking populations in the US and around the world. As Dr. López explained: "The ability to conduct assessment in people's native language is essential to provide correct treatment, offering resources for a better life to groups that are traditionally underserved." The student interns understood the possible repercussions of their work. One of them stated: "Every time I translated a therapy module I kept in mind all the people that this therapy module could potentially help. I also thought about the huge Spanish-speaking population who have HIV that will soon have access to this therapy program as well."

We believe that the success of this internship is based on the cross-sector, cross-disciplinary partnership developed by the Center for Community Based Learning, the Career Development Center, the Spanish Department, and Cedars-Sinai Hospital. By collaborating on all aspects of the internship, from the conceptualization to the logistics, from the connection to the curriculum to the community outreach, we all share ownership of this project, making it viable and sustainable.7 The student interns have played an important role on the longevity of the internship—most have participated for three semesters—sharing responsibilities such as driving back and forth to the hospital and devoting many hours to the revisions of the translations. By working side by side with Dr. Lopez and his team to find solutions to difficult parts of the translation, the interns have proven to be valuable partners for the health care professionals and the community. Likewise, we have taken into account their input to assess and revise the internship, to align our goals and expectations to those of the students and the community partners. We believe that the depth and extent of this collaboration has shifted the students' orientation from helpers to partners. Unlike the class, which was confined to a single semester, the internship provides the space to sustain a project with the community partner over several consecutive semesters, from initiation of a project through completion. Through their work and their reflections we have been able to see their growth as engaged citizens and leaders.

The Research Project

The objective of our collaborative research was to learn about the pedagogical value of translation as a service-learning component in language teaching and, in the process, to study the impact on the students and the community. Part one was a case study of the translation internship at Cedars-Sinai Hospital through interviews with the student interns, Dr. López, and his team. After extensive research in the fields of sociolinguistics, applied linguistics, and the scholarship of engagement, we developed a series of research questions around three issues: language development, civic engagement, and professional preparedness. The participants' responses to our in-person interviews indicated that the pedagogical, pre-professional, and civic goals identified in scholarly studies were fulfilled by the internship. All of them agreed that the internship promoted meaningful and interdisciplinary learning and increased biliteracy development, self-reliance, self-confidence, awareness, and pride. A preliminary version of our findings came together as a poster presentation for the Undergraduate Summer Research Conference at Occidental College, and was later extended to a PowerPoint and presentation at the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages.

Part two of our project, analyzing reflections of the students from the Spanish 211 course vis-á-vis perceptions of the staff from the Public Counsel, is still underway, but parts of it have been included in this piece.

Conclusion

Service-learning is never a transparent activity that accomplishes exactly what the instructor wants to achieve (Butin 2010). That is very true in our case, for we could never have anticipated the transformative nature of the partnerships that we formed by including community-oriented translations in our curriculum. Our collaboration with the Center for Community Based Learning, the Career Development Center, faculty members from other departments, the students, and the community has elevated our teaching and learning goals, increased our public awareness, and fostered meaningful civic engagement. It has also sparked our interest in conducting research to deepen our understanding of service-learning and its implications in our teaching and scholarship. We thus are committed to sustaining these partnerships and look forward to new opportunities of finding meaning through collaborative practices and inquiry.

Notes

1 Our course is entitled Advanced Spanish for Native Speakers because it is open to all students who speak Spanish with a native fluency, whether they are heritage speakers who learned the language as part of their cultural heritage or environmental speakers who learned Spanish in their local or international communities.

2 Following the recommendations of the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages in its National Standards for Foreign Language Education (1999), many Spanish instructors are working towards greater connections with their neighboring communities. This teaching and scholarly trend is documented in several volumes of collected articles, such as Construyendo Puentes (Hellebrant and Varona 1999) and Juntos (Hellebrant, Arries, and Varona, 2003), and the most recent special focus issue of Hispania (2013).

3 I subscribe to the model of transformative partnership proposed by Stewart and Alrutz in which partners should expect some kind of sustained commitment and change (2012, 47).

4 The pedagogical value of activities and assignments that enhance native speakers' awareness of language variation has been underlined by numerous teachers and critics, as demonstrated in Said-Mohand (2011, 94).

5 The California Education Code 48985; 51101; 51101.1; 34 CFR 200.36, as well as the LAUSD Parent-Student Handbook, clearly affirm that "schools shall take all reasonable steps to ensure that all parents/guardians who speak a language other than English are properly notified in English, and in their home language of the rights and opportunities available to them."

6 Along these lines, Calderón and Cadena reflect on the advancement of social justice achieved by simple service-learning projects such as helping immigrant workers obtain their identification cards.

7 The internship announcement shows how the responsibilities are divided among the different collaborators.

Works Cited

American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages. 1999. National Standards for Foreign Language Education. www.actfl.org.

Bugel, Talia. 2013. "Translation as a Multilingual and Multicultural Mirror Framed by Service-Learning." Hispania 96 (2): 369–382.

Butin, Dan W. 2010. Service-Learning in Theory and Practica. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Calderón, José, and Gilbert Cadena. 2007. "Linking Critical Democratic Pedagogy, Multiculturalism, and Service Learning to a Project-Based Approach." In Race, Poverty and Social Justice, edited by José Z. Calderón. Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Hellebrandt, Josef, Jonathan Arries, and Lucia Varona, eds. 2003. Juntos: Community Partnerships in Spanish and Portuguese. vol. 5. Boston: American Association of Teachers of Spanish and Portuguese Professional Development Series Handbook.

Hellebrandt, Josef, and Lucia T. Varona, eds. 1999. Construyendo Puentes (Building Bridges): Concepts and Models for Service-Learning in Spanish. Washington, DC: American Association for Higher Education. Hispania. 2013. 96 (2).

Said-Mohand, Aixa. 2011. "The Teaching of Spanish as a Heritage Language: Overview of What We Need to Know as Educators." Porta Linguarum 16: 89–104.

Stewart, Trae, and Megan Alrutz. 2012. "Meaningful Relationships: Cruxes of University-Community Partnerships for Sustainable and Happy Engagement." Journal of Community Engagement and Scholarship 5 (1): 44–55.