When the American Council of Learned Societies (ACLS) issued its "Report of the Commission on the Humanities" in 1964, it argued that the humanities, "a body of knowledge and insight" that included the "study of history, literature, the arts, religion, and philosophy," was critical to the future of American democracy as a necessary counterweight to a Cold War focus on science and technology (1). But the space race and science funding were not the only lurking threats. As the report's writers looked out over the nation in the early 1960s, they saw leisure as one of the most serious perils facing Americans. They were not alone. In a time when affluence seemed unending, pundits and scholars often wrung their hands about the effects such unprecedented freedom would have on the American character (Binkley 2007). The ACLS report echoed these concerns by predicting that with fewer hours spent at work, Americans would fall into an "abyss of leisure." Tempted by "trivial and narcotic amusements" their minds and mettle would weaken (5). The humanities were the appropriate antidote, which, with their sober questioning about human existence, would act as a bulwark against idleness.

While concerns like these seem quaint today, when the most pressing problem facing many Americans is how to find any job at all, this argument is not just a mere curiosity of the past. Hugely influential, the ACLS report spurred the passage of the National Foundation on the Arts and Humanities Act in 1965, which created the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) and the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH).1 While the ACLS included the arts within the humanities, Congress separated them, creating a highly dubious distinction. The humanities' anti-play attitude is, in part, a result of that division.

As Jamil Zainaldin, historian and director of the Georgia Humanities Council, argues, "It was the most ambitious piece of cultural legislation in American history" (2013, 30). Growing out of the ACLS and with its scholarly inclinations, the NEH and its partners, the state humanities councils, adopted much from the report, including what might be called an anti-play methodology that prized intellectual activities over fun and games.This has particularly affected civic engagement efforts. Since their founding, the NEH and state humanities councils have focused on civic engagement, with the humanities councils leading the charge. As James Veninga, the director of the Texas Council for the Humanities, wrote, "If there is one contribution that state councils have made to American democracy during the past twenty-five years, surely it is this—the expansion of public opportunities whereby citizens have an opportunity to meet and learn" (1999, 150). Former Chairman of the NEH James Leach agreed, seeing the state humanities councils as best suited to address the "need in a democracy for the public to probe deeply the issues of the day in order to ensure thoughtful debate that accommodates and respects disparate views" (2011). Overwhelmingly, civic engagement programs in the public humanities concentrate on intellectual endeavors, from scholar-led public lectures on contemporary topics to community conversation programs centered on written texts. Such programs, though, are often exclusionary through their very structures. Conversation programs around written texts, for example, privilege native speakers who are comfortable expressing themselves in front of groups of strangers.

However, some public humanities organizations, recognizing the limitations of traditional civic engagement activities and wanting to reach new audiences, have embraced play. This essay offers preliminary thoughts on the use of play as a tool for civic engagement in the public humanities. Scholars in fields ranging from literature to women's history to performance studies have argued that play can have a public component (Bakhtin 2009; Enstad 1999; Schechner and Brady 2013). For the purposes of this essay, sports, games, dress-up, make believe, and playfulness are included under the rubric of play. While it is a growing area of scholarship, video games will not be a focus. Public humanities programs privilege face-to-face encounters and allocate their resources for real-world interaction, which is the topic here.

What does play as a practice offer those of us who work in the public humanities? How have state humanities councils, as the most extensive network of public humanities organizations in the country, used play? Where can we look for other models of the humanistic use of play as we seek ways to revitalize civic engagement and democracy? I focus on four uses of play: as a topic of historical inquiry, as physical activity, as civic engagement, and as role-playing the past. Using case studies ranging from a group cycling tour to games played in urban spaces, I show that play connects individuals to each other affectively, creating social solidarity, while offering the opportunity to collectively envision changed social relations. More specifically, play benefits the public humanities in four ways that are key to civic engagement. By bonding people to each other, creating common experiences that can be the starting point for dialogue, play inculcates a sense of community where none existed. It allows people to break out of their alienation through new kinds of interactions with low consequences. Because it has an emotional aspect, play urges people to feel in addition to think, strengthening their ties to each other in ways that intellectual engagement alone cannot. Following from these aspects, play can be used for civic engagement, drawing people into conversations and actions that are focused on shared issues, which is the heart of democracy.

Finally, play is prefigurative. As children well know, through play we recreate the world as we want it to be, envisioning and enacting new relationships. Ever since the National Foundation on the Arts and the Humanities Act of 1965 asserted that the humanities encourage "wisdom and vision" in its citizens, the public humanities has been concerned with imagining a collective future. The belief that knowledge of the human condition can be a guide to civic action is especially critical now when the humanities are being assailed as having little or no value.2 But in order to become relevant to twenty-first-century democracy, the humanities must adopt new methods and practices. Play can be used communally to enact a world with alternative values, even if only for beautiful, fleeting moments.

This essay is based on exemplary, though understudied, public humanities programs from around the country. While state humanities councils, their grantees, and their partners have used play in a variety of interesting ways, they have not analyzed play critically. Public humanists often work in isolation, with little sense of what else has been tried and what has succeeded or failed. In this essay, I archive and connect disparate projects as a call for more work that does the same in order to create spaces for public humanists to learn from each other.

Dancing the Revolution

The publication of Robert Putnam's sociological analysis of civic engagement, Bowling Alone, started a national debate about contemporary citizenship (Putnam 2001). Arguing that Americans were much less involved in their communities today than had been the case in the past (with the demise of the bowling league as his central, play-based example), Putnam's work augured a sad future in which alienated individuals refused to see their mutual dependencies and our civic fabric frayed irreparably. To combat this, universities, foundations, government agencies, and other cultural institutions sought to spur civic engagement through programs, service learning courses, and grants. The Pew Charitable Trust's definition of civic engagement as "individual and collective actions designed to identify and address issues of public concern" focuses rightly on questions of the common good at the heart of civic engagement (NPSCSI 2009).

Play's civic potential derives from its communality. While an individual can play by him or herself, most play takes place with others. Play thus offers a solution to the problem posed by sociologist Craig Calhoun, who argues that individuals need to feel a sense of solidarity—what he calls "peopleness"—in order for democracy to work. He writes that democratic states "require a form and level of 'peopleness' that is not required in other forms of government" because "they offer a level of inclusion that is unprecedented—the government of all the people . . . they place a new pressure on the constitution of the people in sociocultural and political practice" (Calhoun 2002, 153). By incorporating play within the public humanities (the sociocultural realm), greater social solidarity can be created, strengthening the basis of democracy. Cultural historian Johan Huizinga, the creator of play studies, notes that players form a "play-community" which lasts long after the game is over:

[N]ot every game of marbles or every bridge-party leads to the founding of a club. But the feeling of being 'apart together' in an exceptional situation, of sharing something important, of mutually withdrawing from the rest of the world and rejecting the usual norms, retains its magic beyond the duration of the game (Huizinga 1955, 12).

Play catalyzes bonding, creating a sense of community where none existed before. Historians and sociologists have supported Huizinga's theory with case studies. Patricia Anne Masters' research on the Philadelphia Mummers, a group of social clubs that for generations have created elaborate costumes and musical routines to compete during an annual New Year's Day parade, suggests the durability of play-communities (Masters 2007). While there are prizes for the winning clubs, they spend far more in creating their costumes and floats than they receive in winnings. It is the sense of communal engagement, social ties, and pride that motivates the Mummers to continue. While such longevity is laudable, the Mummers have lasted in part because they have controlled who has been allowed to play. Women and African Americans, for example, have participated in the parades only in the last few decades. Tightly knit play communities persevere due to their homogeneity and like-mindedness, a valid warning that not all play or communities are democratic and that social capital, an unqualified good for Putnam, is also a tool of exclusion (Adkins 2005).

Progressive social change can result from play. As Benjamin Shepard has chronicled, activists fighting for funding for AIDS research, to protect community gardens in New York City, and against globalization have all used play to intervene in civic issues and to prefigure different social relations. Such actions—like releasing crickets at an auction of public land—are "a device for group solidarity" that "disrupt what is wrong with the world and generate images of what a better one might look like" (2011, 9). These activists learned such lessons from earlier movements. Civil rights activists of the mid-twentieth century often sang together during marches and in prison. Feminists, too, used play to challenge racial and gender inequality, as historian Anne Enke shows in her analysis of a black women's softball team in Detroit in the 1960s. "Without manifestos or a named feminist agenda, the Soul Sisters publicized a particular non-normative gender performance through aggressive occupation of civic athletic space unusual for women's teams at the time, and they worked to make public athletics more accessible to young women and girls" (Enke 2007, 109). As she suggests, play is a sphere where battles over power can be fought, making it productive for the creation of an engaged citizenship. While in this instance the result was more equitable play for women of all races, play also has a dark history, as powerfully expressed in photos that capture the carnival atmosphere that accompanied many lynchings in early twentieth century United States. For public humanists, understanding both the progressive and regressive aspects of play is necessary in order to utilize it critically.

Being Apart Together: Four Strategies for Using Play

While the previous examples highlight the political nature of play, here I examine programs that connect play to civic engagement's values of public interaction, community connection, and interventions into shared social problems. From using play as a historical topic, to role-playing the past, public humanists have experimented with play. Every year, for example, state humanities councils fund hundreds of historical conferences, symposia, and museum exhibits, with a small number of these taking the history and cultural study of sports as their topic. Sports history, as an accepted subfield of a long-established traditional humanities discipline, is an ideal opening wedge for bringing play into the public humanities. Sports shape communities economically, socially, and politically—from the floating of public bonds to pay for a new stadium to debates over team mascots. Understanding this, the Smithsonian Institution's Museum on Main Street program's newest traveling exhibit, Hometown Teams, will tell the national story of sports in America while the state humanities councils that host the exhibit will use it to highlight local stories in additional exhibits and public programs.

Like all games, sports reflect cultural beliefs while also creating an idealized version of society, one with clearly demarcated rules that ensure fair play, an apt metaphor for democracy. As one scholar of play has argued, "Games are based typically on equality of opportunity among participants. Outside statuses are disregarded, games typically begin from conditions of absolute equality" (Henricks 2006, 132). While sports are competitive, engaging in sports (whether as player or fan) creates a shared heritage that can create play-communities that bond strangers through collective remembering. In their conference "Playing on the Plains: Sports and Recreation in South Dakota," the South Dakota Historical Society found that communal remembering was an unexpected outgrowth of focusing on play. The conference's fourteen invited speakers discussed topics ranging from "Boarding Schools and the Growth of Native American Basketball," to "The Governor's Hunt and the Importance of Pheasant Hunting to the State of South Dakota." The theme of play did not extend to the method of delivery—presentations were lectures or panel discussions—and included both traditional scholars and others, such as sports journalists and the governor of South Dakota. While some participants felt that the topic was insufficiently serious for a history conference, leading to lower attendance than in previous years, audience evaluations suggested that those who came learned a great deal. They even pushed back at the presenters by arguing that stories of gender inequality in sports should have been threaded through the course of the conference rather than concentrated only in one session (South Dakota Historical Society 2012). Of particular value for community bonding was the showing of South Dakota Public Broadcasting's documentary Kings of the Court (2012) about the state's boys' basketball tournaments. Although the topic was playful, these responses showed serious engagement with the issues. Screened during a luncheon, viewers valued the attention given to local communities. Ironically, the rivalry and competition captured on film led to greater interaction and sharing by its viewers.

Play can be more than a topic—it can be a methodology. Physical activity attracts people who otherwise would not attend a public humanities program and, as program evaluations show, deepens the humanities experience by connecting intellect, body, and emotion. Since 2008, the Guam Humanities Council has organized the I Tinaotao 5K Run, which brings together a group of runners in a competitive format that highlights an anticolonial history. After being a Spanish colony for more than three centuries, Guam became a territory of the United States during the Spanish-American War in 1898, though the Japanese claimed it during World War II. These successive waves of colonization ensured that the Chamorros (the indigenous people of the island) were forced to adapt their social, cultural, and religious practices in accordance with their conquerors. It was only with the Guam Organic Act of 1950 that Guam had its own civilian government and not until 1968 that the people could elect their own governor.

With ties to the federal government, the Guam Humanities Council must balance the needs of its people, who include Chamorros and military personnel stationed on the island, with the dictates of federal funding. Given the island's complex history, one of the main goals for the 5K run is to showcase indigenous culture and historic sites. Cultural presentations take place along the route, which includes historically significant places like the Dulce Nombre de Maria Agana Cathedral-Basilica (see Fig. 1) and the Plaza de Espana. The run also encourages "an active lifestyle and environmental appreciation among our residents" (Guam Humanities Council 2013). But why a run? Certainly an exhibit or website could introduce people to Guam's heritage. By physically moving from one historic site to the next, the event gives participants an embodied understanding of the relationship between past and present and different locations and brings well-wishers to the sites to cheer on the runners. Cultural presentations, like ethnic music performances, emphasize the historic importance of spaces that might not otherwise be noticed. Physical activity links "environmental appreciation" with historical knowledge, showing how place impacts culture.

The Illinois Humanities Council's now defunct program Velosophie utilized a similar method—group bike tours—but connected them with community conversations. As a report prepared by the Illinois Humanities Council notes, in Ancient Greece athletics and the humanities were not disconnected as they often are today. "It is the aim of Velosophie," says the report's writer, "to erase and reconstitute these separate spheres by offering them as a synergistic experience, a journey of the mind in tandem with a journey of the body" (Illinois Humanities Council 2006a).3

Cycling was not merely added to a community conversation; it fundamentally changed the way that participants approached the readings and shaped their viewpoints. Physical activity structured the conversational outcomes. Importantly, too, unlike many other humanities council community conversation programs that bring together groups of strangers with little or no connection to each other, Velosophie was a shared experience. By gathering at the end of a long day of cycling to discuss a text, Velosophie tried to "create or nurture opportunities to think and talk with one another" through common texts that "provide a fresh and neutral common point of reference, allowing conversation to move beyond private experience, professional expertise, or settled opinion" (Illinois Humanities Council 2008). Facilitators ensured that the discussions connected the shared experience of the group cycling tour with the texts, envisioning a symbiotic process in which play informed and deepened community engagement.

A small sample of evaluations from participants in the 2006 Velosophie program on "Pain and Pleasure" suggests that the program encouraged participants to reflect on their bodily experiences through the texts. As one rider commented, "I did think about various aspects of pain & pleasure while on tour." While she focused on her solitary experience (thinking about the themes, rather than discussing them with others), others commented more directly on the interactions that brought this activity into the realm of the civic. One said that the "discussions were ones I wish I could more often initiate over dinner with friends." While we would expect that a program like Velosophie would try to mirror what happens among a group of friends, in this instance the rider is acknowledging the barriers to probing conversation that the habits of friendship can bring. The shared experience of cycling bonded the group. The reading and discussion portion helped structure and ease people's interactions as they rode together. Another rider noted "lots of minor discussions during the week" among participants about the tour's themes (Illinois Humanities Council 2006b). As Putnam argues, people must feel connected in order to create an active civic sphere: "Informal types of sociability . . . are very important in sustaining social networks" (Putnam 2001, 95). They are built through interaction, what Putnam calls "doing with" (as distinct from "doing for") others. Velosophie can be seen as Putnam's "doing with" put into action.

Physical activity in western culture is often utilized as a means of reshaping the self (Foucault 1988). The humanities views intellectual effort similarly—one can become a better, more informed, more thoughtful, worldly person through education. Individuals may gravitate towards one or the other in their efforts at self-making; Velosophie offered participants a chance to merge these two poles of the American impulse towards self-transformation, the athletic and the intellectual, showing their common core in defining the self. The cycling tour filled days with biking; nights were free. As one rider responded to a question of why she or he signed up for the discussion program, "to format my nightly activities." While this individual would have gone on this cycling tour anyway, the reading-and-discussion helped to give his or her time a shape, to structure what otherwise would have been free time into an activity deemed more productive in ways that even the ACLS would laud. Another rider summarized, "It accomplished its declared purpose—to create a different frame through which to see and relate to other riders. It generated a common experience & vocabulary & reference" that brought riders who didn't know each other together and used play to augment each experience (Illinois Humanities Council 2006b). The civic engagement aspect of this program would have been further strengthened had the discussion sessions focused on contemporary social problems rather than philosophical questions.

Play as a topic that encourages collective remembering and as physical activity that can be both communal and intellectual merge in the extraordinary Spirit & Place Festival, organized by the Polis Center at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis (IUPUI). Play was the festival's theme in 2012, which included events about play (Insert Coin to Play, about video games), that used play (Musical Machinery Workshop), and play-based interactive experiences (GAMESpot). Overall, forty-six programs, presented by ninety-eight partner organizations, drew more than 19,000 people over the course of ten days. The goal of the Spirit & Place Festival is civic engagement. As the organization explained in its 2012 brochure, the festival stimulates "civic vibrancy by linking disparate people and organizations, mobilizing ideas, and forging personal and institutional connections in a time when civic participation is in decline" Polis Center 2012). Local arts, humanities, and religious organizations propose festival events, which are judged according to a theme selection rubric that places "civic engagement" and "public imagination" at the top. A keynote public conversation closes the festival. The report on the 2012 Festival noted that attendance at the conversation has steadily decreased over time, suggesting that the broadcast model, in which the audience listens as others discuss a topic, has lost currency to more interactive programs (Polis Center 2012a).

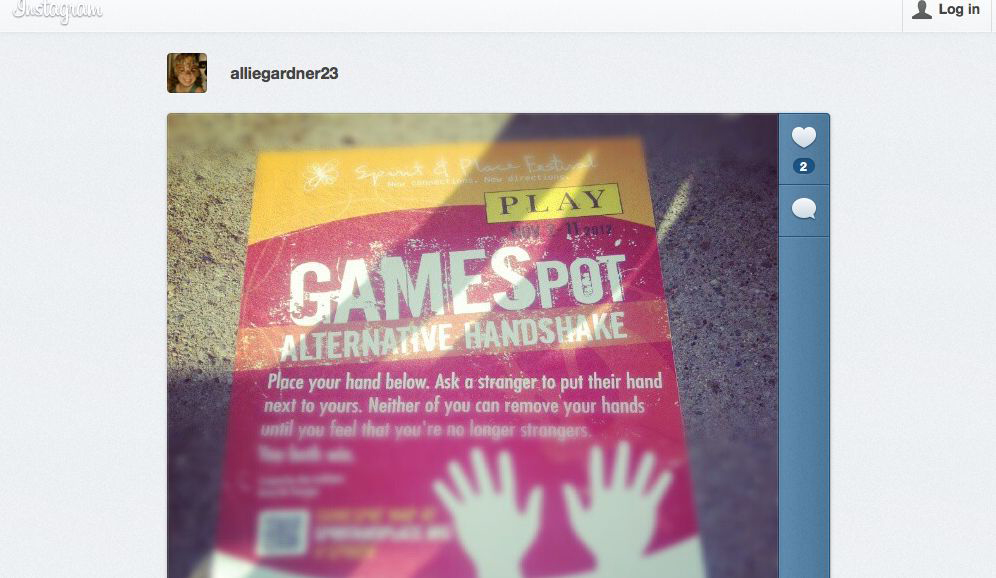

Indeed, one of the most successful programs of the 2012 Spirit & Place Festival was a series of place-based games called GAMESpot, which uses sidewalk decals that tell passersby to play a site-specific game (click here for a map of all GAMESpot locations). "Architectural Charades," for example, asked a player to "choose a visible building and try to get the other players to correctly guess which building you're thinking of by doing a physical impression of it without speaking." This activity encouraged players to engage with the built environment—something they may never have done before—in a playful way. Rather than only seeing buildings for their function, the game brought a lighthearted attitude to the city street. While postindustrial cities have been envisioned as landscapes of play for tourists and the wealthy by developers who build sports arenas, upscale entertainment complexes, and convention centers, GAMESpot offered a different kind of urban play, which engaged people affectively, physically, and creatively with the city (Norris 2003; Polis Center 2012a).

Other games encouraged interaction with strangers. The "Alternative Handshake" decal included the image of two handprints next to each other and asked a player to place their hand in one (see Fig. 2). That player is then instructed to "ask a stranger to put their hand next to yours. Neither of you can remove your hands until you feel you're no longer strangers. You both win." Although it's unclear whether anyone attempted the "Alternative Handshake," social media shows that other interactive activities did bring strangers together. "Abbey Road" asked players to recreate the iconic Beatles album cover. Facebook comments on a picture of a group playing the game note that a young woman who was a stranger to the others saw what they were doing and joined in the activity, which was uploaded as a picture to the site (see Fig. 3). Commenters raved, saying "Love! Love!! Love!!!"

As Zygmunt Bauman has noted, the postindustrial city has been designed to reduce the possibility of interactions, due to the perception of danger from unknown others. Games like those described here renegotiate relationships between individuals and the city and between individuals. They are only lightly rule bound, offering opportunities for chance and spontaneity that are impossible in more scripted kinds of play, but can be completely absorbing. GAMESpot utilized play defined both as activity and as an attitude of playfulness, and was, according to festival organizers, "stunningly successful with extensive community participation and spectacular branding value" (Polis Center 2012). However, like Velosophie, the organizers did not take the next step of connecting the positive feelings engendered by the games to social questions about the role of development or gentrification in reshaping the city that logically follow from them.

As these varied examples show, play can create civic engagement through sharing stories, physical activity, a playful attitude, and interaction with strangers. There is another aspect of play, though, that when added to these offers a powerful model for civic engagement—role-playing. Theorists of play dating back to Huizinga have defined the loss of the self as an essential aspect of play, which shows its relationship to theater and ritual (Schechner and Brady 2013). How can the public humanities encourage civic engagement through role-playing? After all, the fundamental role to be played in a democracy is that of citizen, which is predicated on the notion of a rational person with rights and responsibilities. Role-playing seems, at first glance, to be its opposite. However, historical role-playing can spur public engagement and discussion about the past even though, as public historians like Cathy Stanton have argued, making connections between historical issues and the present can be difficult (Stanton 2006). The following example of using role-play to engage people with history demonstrates how it can be tied to civic engagement. Even more powerfully, the connections this makes are affective as well as intellectual.

Annually since 1994, the Baltimore neighborhood of Hampden, a formerly predominantly white, blue-collar neighborhood experiencing gentrification, has become the setting for HonFest, a street festival created by the owner of a neighborhood cafe. While this festival was not the product of a public humanities organization, it is a public heritage event, which utilizes historical themes and images. The festival "celebrates" a white, working-class female icon known as the Hon, though many in the neighborhood are critical of it. The archetypal Hon is a 1960s diner waitress, the kind of blue-collar woman who asked "how ya doin', hon?" when she took your order and meant it. The Hon is best known for her look—a carefully curated collection of midcentury kitsch like cat's-eye glasses, blue eye shadow, and beehive hairdos—and attitude. As Linda, a woman I interviewed at HonFest in June 2008 explained, "Hons were big-hearted, gregarious women who worked hard and played hard. . . . They appreciated a raunchy joke and only made fun of people who knew it was a joke."

The creation of the Hon as icon is already playing with the past. Prior to HonFest, no one had used the word Hon to describe a type of person. It was simply a shortened form of the word "honey," used within a particular demographic. But since that time, many have adopted it as the heritage of the neighborhood and city, though not without controversy. As Denise Whiting, the festival's creator, suggested in a June 10, 2010 article in The Baltimore Sun, "The genius of Honfest is, it gives people permission to have fun and lets them step outside themselves for a moment. They can let their defenses down and be the person they are inside — the genuine person who has heritage in their heart" (Sessa 2010). Whiting's statement suggests the potential for civic engagement. A shared heritage centered on the Hon, based in part on playfulness and role-playing, allows individuals to "step outside themselves for a moment" and become part of a group—Hons or Baltimoreans. Missing, though, is the fact that the heritage of Hon is not shared by all, as demonstrated in 1994 when a state legislator advocated permanently changing the "Welcome to Baltimore" sign on Interstate Highway 295 to read "Welcome to Baltimore, Hon." Mayor Kurt Schmoke refused, seeing Hon as meaningful primarily to Baltimore's white, working-class population, a group whose numbers had been decreasing for decades.

HonFest, as an example of public play, is prefigurative. It is a vision of what its creators believe the city of Baltimore and Hampden should look like, and who should represent the neighborhood. Ironically, but not surprisingly, HonFest's "celebration" of working-class women became popular just as blue-collar residents were leaving the neighborhood. The use of Hon as an image for Hampden or Baltimore must be understood in this context, as new residents moved there in part because of the neighborhood's reputation as being quirky and safe in contrast to the larger city of Baltimore, which has wrestled with high crime rates. Furthermore, Hampden's history of using de facto measures to maintain racial homogeneity has given it a deserved reputation as unfriendly to people of color. But on the streets of Hampden during HonFest, women dressed in outrageous costumes as Hons create a different conception of public space. By role-playing as Hons, they playfully enact the Hon persona in public, express their creativity through their carefully composed outfits that reference white, working-class women's history, and, for a core group, connect with their family history and others through discussions of the lives of white, working-class women in Baltimore. Such acts are civic in nature and, taken as a whole, offer an example of the civic possibilities of role-playing.

One of the Hons' central activities is playing with the past through costuming. While many women who attend HonFest purchase neon-colored beehive wigs, others create outfits and personas that reference the history of white, working-class women's lives. As historians like Nan Enstad have examined, working-class women used mass-produced cheap fashion to create a class-specific culture distinct from middle-class women (Enstad 1999). Hons focus on the post-World War II period, an era of working-class stability and affluence, especially for whites, that was expressed in dazzling new styles, from highly teased beehive hairdos to pointed cat's-eye glasses that looked like the fins on a new Oldsmobile. By carefully (though exaggeratedly) recreating these styles, Hons revive a class-specific taste culture.

In their revivals, Hons may also attempt to draw connections to Baltimore through references to history, geography, or folklore. Charlene, who became Baltimore's Best Hon in 2009, for example, created the identity of Blaze Char for her Hon performance, a play on the name of the famed Baltimore burlesque queen, Blaze Starr (see Fig. 4). Not only is Charlene's style exuberant and eye-catching, her outfits carefully honor Baltimore's past, including the use of painted screens, a Baltimore folk tradition dating back to 1913. Window screens were decorated with images that allowed the people living in the houses to see out, but not for passersby to see in. Charlene, who took a class on screen painting, created two Hon outfits that included painted screens, including one of a pink flamingo, a reference to Baltimore native son John Waters' film of the same name. In doing so, Charlene exhibited Baltimore folk art as part of a reenactment based on a popular-culture icon and her working-class family history. Indeed, when she described her image of a Hon in 2012, Charlene talked about her grandmother, who served as a model for the white, working-class icon. But she was not alone in using the role-playing of HonFest as a means of publicly honoring women of the past. Susan, who won Baltimore's Best Hon competition in 2005, dressed up as a way to pay homage to her mother, who raised her as a single parent, helping to ensure that she rose from the working to the middle class. When she won the competition, Susan wore her mother's cat's-eye glasses as a memorial. These connections spur many conversations at HonFest. As neighborhoods like Hampden eliminate working-class public spaces like diners and dime stores in favor of privatized spaces or stores geared for middle-class consumers, at HonFest women dressed as Hons reclaim public space in order to joke and reminisce about their own class histories in a kind of vernacular heritage (Smith 2006).

All of this is done through playfulness. Hons joke, laugh, and flirt with strangers because they are role-playing. By taking on this other persona, these women break down the barriers to civic engagement, which includes fearfulness of strangers in public. While these interactions usually remain playful, fairly often they lead to discussions of Baltimore's history. For example, in 2008, I observed two middle-aged women at HonFest dressed as Hons, talking about how their ascension into the middle class was made more difficult due to their accents, which marked them as being from Baltimore's working class. Such a conversation, which took place in a public space, offered a rare critique of the American mythology of upward mobility due to effort.

Role-playing, and play more broadly, allows individuals to tap into emotions, affecting the depth of engagement. The women at HonFest, like any serious reenactor who returns every year and invests time and money to play with other identities, are drawn by an emotional connection that not only serves their individual purposes but also connects them with a community. By playing a role, these people actively create a public sphere. However, such role-playing can be problematic. The use of heritage discourse at HonFest erases the racial conflicts that were central to the creation of neighborhoods like Hampden so that new middle-class residents and tourists can play at being working class for an afternoon. At the same time, thousands of people are drawn to this playful environment, suggesting that there is room for public humanists to involve themselves in such activities, helping to contextualize and historicize them, while leaving their pleasurable aspects intact.

In assessing these examples of play within the public humanities, I have intended to archive and connect what are otherwise ephemeral and discrete programs. While more work is needed in this area, this preliminary investigation suggests certain model programs that join play, public humanities, and civic engagement that could be expanded. Velosophie's merging of shared physical activity with facilitated discussion melds the body and mind in productive ways. Imagine using this model with discussions focused not on abstract philosophical ideas, but on local issues relevant to groups of cyclists, such as climate change or urban sprawl. GAMESpot's subversion of the atomization of contemporary urban life is valuable, but could be made more so if combined with a specific action to follow—perhaps by including information on zoning laws or proposed development projects for players to read and discuss afterward. HonFest also creates community in the midst of urban anomie, but given the history of racism and gentrification in the neighborhood there is more to be done. Giving festival attendees the opportunity to tour a historical exhibit about the women of the neighborhood, perhaps staffed by Hon docents, would deepen the impulse towards historical reenactment and contextualize the event, while acknowledging what it does well—bringing people together.

Classrooms, too, can be invigorated through this kind of play. Reacting to the Past is an innovative pedagogical model that utilizes historical role-playing in order to turn students into participants in their education through their need to immerse themselves in primary sources in order to effectively "play" the game. The teacher becomes the game master with students running the classes, learning scholarly writing through papers about the topic, and public speaking by giving speeches to convince fellow players to take their side. Students in Reacting classes exhibit greater engagement in their course materials; while it was developed for college classrooms, there are indications that it could work in high schools as well (Higbee 2008).4

When Martha and the Vandellas sang "Dancing in the Street" in 1964, the song equated joyous physical activity with politically motivated revolt in the face of racism and urban disinvestment. While the examples examined here are not calling for revolution, they share the belief that play can lead to civic engagement—in spite of the fact that the public humanities has traditionally privileged rational and intellectual activity over play. Clearly, both are critical to a revitalized democracy. As Craig Calhoun argues, social solidarity "needs to be a realm of cultural creativity and rational discourse, and a realm of mutual engagement" (2002, 171). Play—as "cultural creativity" and "mutual engagement"—can spur social solidarity, whether through reminiscing about local teams and sport heroes, shared physical activity, or role-playing. Incorporating play as one of the methods of the public humanities strengthens its ability to engage with a diverse public. However, if we are interested in addressing social inequities, than both civic engagement and play are insufficient in isolation. Used together in critically informed ways that understand their respective limitations, they represent a potential source of energy for the public humanities. While its roots in the scholarly realm make this a radical step, state humanities councils and other public humanities organizations have already made much headway in shifting the public humanities away from its elitist origins. Embracing play would be another powerful way to extend this democratizing impulse.

Notes

1 While the ACLS included the arts within the humanities, Congress separated them, creating a highly dubious distinction. The humanities' anti-play attitude is, in part, a result of that division.

2 In 2012, the state of Florida debated whether to charge college students with a humanities major higher tuition, in order to incentivize focusing on areas of high job growth, such as engineering, even though those courses cost universities more to provide. This proposal came amid debates about the value of the humanities in terms of employment and education, which spurred Congress to commission a report from the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, "The Heart of the Matter," that argued that the humanities are intrinsically important to a vibrant American economy, especially in the face of greater global competition.

3 Many of the sources used in this section are internal organizational documents about specific programs provided to me by interviewees at those organizations.

4 I saw firsthand the effectiveness of the Reacting to the Past model during a visit to a class taught by Dr. Abigail Perkiss, Kean University, who used the module, "Greenwich Village, 1913: Suffrage, Labor and the New Woman," for a historical methods course for undergraduates during Spring semester 2013. The students learned how to play the game over the course of the period, many of them becoming caught up in it and urging their fellow classmates to take their point of view in a historical debate over women's rights.

Works Cited

ACLS (American Council of Learned Societies). 1964. Report on the Commission on the Humanities. New York: ACLS.

Adkins, Lisa. 2005. "Social Capital: The Anatomy of a Troubled Concept." Feminist Theory. 6 (2): 195–211.

Bakhtin, Mikhail. 2009. Rabelais and His World. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Bauman, Zygmunt. 2000. "Urban Battlefields of Time/Space Wars." Politologiske Studier 7. Accessed 15 January 2009. www.politologiske.dk/artikel01-ps7.htm.

Binkley, Sam. 2007. Getting Loose: Lifestyle Consumption in the 1970s. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Calhoun, Craig. 2002. "Imagining Solidarity, Cosmopolitanism, Constitutional Patriotism, and the Public Sphere." Public Culture 14 (1): 147–171.

Enke, Anne. 2007. Finding the Movement: Sexuality, Contested Space, and Feminist Activism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Enstad, Nan. 1999. Ladies of Labor, Girls of Adventure: Working Women, Popular Culture, and Labor Politics at the Turn of the Twentieth Century. New York: Columbia University Press.

Foucault, Michel. 1988. "Technologies of the Self." In Technologies of the Self: A Seminar with Michel Foucault, edited by Luther H. Martin, Huck Gutman and Patrick H. Hutton. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press.

Guam Humanities Council. I Tinaotao 5K Historical Run. Accessed 21 March 2013. http://www.guamhumanitiescouncil.org/5krun.html.

Henricks, Thomas S. 2006. Play Reconsidered: Sociological Perspectives on Human Expression. Chicago, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Higbee, Mark D. 2008. "How Reacting to the Past Games 'Made Me Want to Come to Class and Learn': An Assessment of the Reacting Pedagogy at EMU, 2007–2008." The Scholarship of Teaching and Learning at EMU 2 (article 4). http://commons.emich.edu/sotl/vol2/iss1/4.

Huizinga, Johan. 1955. Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play Element in Culture. Boston, MA: The Beacon Press.

Illinois Humanities Council. 2006a. Internal Report on Velosophie. Chicago, IL.

———. 2006b. Internal Summaries of Evaluations of Velosophie. Chicago, IL.

———. 2008. Internal Overview of Velosophie. Chicago, IL.

Leach, Jim. 2011. "Re-Imagining the American Dream: The Humanities and Citizenship." National Endowment for the Humanities. http://www.neh.gov/about/chairman/speeches/re-imagining-the-american-dream-the-humanities-and-citizenship.

Masters, Patricia Anne. 2007. The Philadelphia Mummers: Building Community Through Play. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Norris, Donald. 2003. "If We Build It, They Will Come! Tourism-Based Economic Development in Baltimore." In The Infrastructure of Play: Building the Tourist City, edited by Dennis R. Judd, 125–167. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe.

NPSCSI (National Park Service Conservation Study Institute). 2009. Stronger Together: A Manual on the Principles and Practices of Civic Engagement. Woodstock, VT: NPSCSI. http://www.nps.gov/civic/resources/CE_Manual.pdf.

Polis Center. 2012a. Internal Spirit & Place Festival Report. Indianapolis, IN.

Polis Center. 2012b. Spirit & Place Festival Brochure. Indianapolis, IN.

Putnam, Robert. 2001. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Touchstone.

Schechner, Richard, and Sara Brady. 2013. Performance Studies: An Introduction. London: Routledge.

Sessa, Sam. 2010. "Honfest 2010 Spreads Its Flamingo Wings," Baltimore Sun, June 10. http://articles.baltimoresun.com/2010-06-10/entertainment/bs-ae-family-hon-fest-20100610_1_honfest-baltimore-icon-denise-whiting.

Shepard, Benjamin. 2011. Play, Creativity, and Social Movements: If I Can't Dance, It's Not My Revolution. New York: Routledge.

Smith, Laurajane. 2006. Uses of Heritage. New York: Routledge.

South Dakota Historical Society. 2012. Internal Evaluation Report for Playing on the Plains: Sports and Recreation in South Dakota. Pierre, SD.

Stanton, Cathy. 2006. The Lowell Experiment: Public History in a Postindustrial City. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press.

Veninga, James F. 1999. "Humanities Councils and the Current Crisis of Democracy." In The Humanities and the Civic Imagination, edited by James F. Veninga, 146–158. Denton, TX: University of North Texas Press.

Zainaldin, Jamil. 2013. "Public Works: NEH, Congress, and the State Humanities Councils." The Public Historian 35 (1).