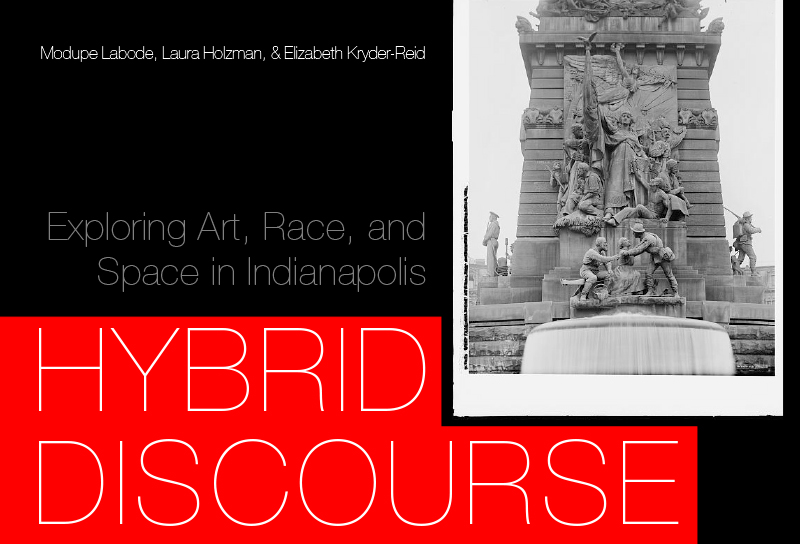

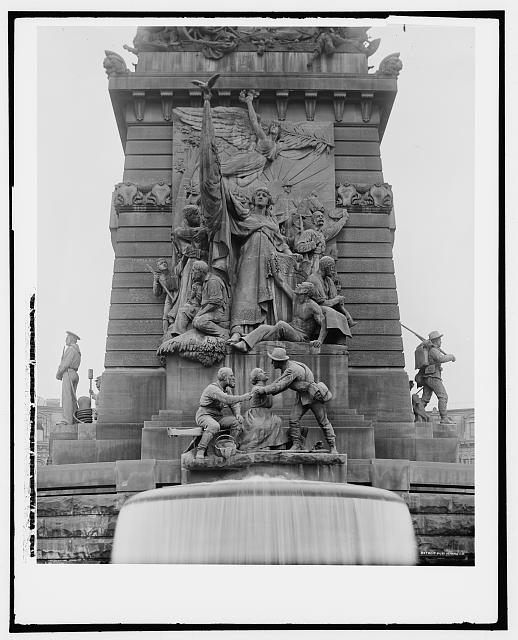

The symbolic center of Indianapolis is the 1901 Soldiers and Sailors Monument located on the central circle of the "Mile Square" plan for the city, which was laid out in 1821 (Scurch 1994, 1007–8). Nearly hidden amid the embellishments on the ornate limestone structure is an African American figure, a kneeling freedman (fig. 1). 1 His outstretched right hand clutches broken shackles, which he presents to an apparently indifferent goddess. A few blocks from the Soldiers and Sailors Monument, the Indianapolis Cultural Trail, a bicycle and pedestrian path, curves through the city's downtown. Public art installations dot the trail.2 Beginning in 2007, a proposed work of public art commissioned for the trail, Fred Wilson's E Pluribus Unum (Out of Many, One), was the locus of vigorous and disjointed public exchanges about race, history, power, and aesthetics—concepts that underpin civic life but are rarely articulated. In December 2011, the sponsoring agency canceled Wilson's commission. The proposed artwork would not be realized, and with the project's termination, there seemed to be little will by the media or others involved in the dispute to publicly engage with the complex issues of art, race, and representation.

Even so, extended debate surrounding the sculpture elicited painful memories, revealed community tensions, and provided opportunities for individuals to express frustrations with long-standing social and political dynamics in the community. These emotions remained raw even after the dispute was no longer in the public spotlight. It appeared that, with the end of formal discussion about E Pluribus Unum, Indianapolis residents lost the opportunity to discuss race and representation in their city. In 2012, however, faculty members from the museum studies program and other departments at Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis (IUPUI) conceived of a symposium to facilitate dialogue about the key themes of art, race, and space that controversy over E Pluribus Unum had raised.3 Building on engaged practices developed at museums and historical sites (Ševčenko 2010; Rosenberg 2011), as well as on existing relationships between faculty members and community partners, the symposium was a hybrid event that combined university and community resources, expertise, and communication practices in a manner that brought together diverse voices in constructive conversation about challenging topics. After further introducing the proposed artwork and the events that led to its cancellation, this article will provide a detailed overview of the structure of the symposium that facilitated constructive conversation around Wilson's work and the broader themes it engaged.

The Indianapolis Cultural Trail and E Pluribus Unum

The Indianapolis Cultural Trail (ICT), a project of the Central Indiana Community Foundation (CICF), was launched in 2006 and completed in May 2013 (Penner 2006, A1; fig. 2). A goal of the eight-mile bicycle/pedestrian path is to connect the downtown's cultural attractions, government buildings, hotels, and entertainment districts. Diverse stakeholders, including art lovers, cyclists, real estate developers, and elected officials, supported the project, and commentators have praised its focus on enlivening downtown Indianapolis. The meaning of "culture" on the ICT is not fixed; trail promoters alternately refer to culture on the site as high-culture venues, such as theaters; popular culture activities, including sports and dining; and cultural objects, such as public art installations.

The ICT not only links cultural districts but also traverses the city's historic landscape of racial inequality. Policies of urban renewal, highway construction, and suburbanization have been formative in shaping Indianapolis's contemporary downtown. The racial politics of these policies, however, are often invisible to the city's twenty-first-century residents. One segment of the ICT runs along Indiana Avenue, a former African American business and entertainment district that flourished during the racial segregation of the first half of the twentieth century. The ICT also proceeds through the IUPUI campus, which stands on what was once the site of a working-class, predominately African American neighborhood, the presence of which is now indicated only through historic markers (Gray 2003, 42, 46–63; Mullins 2003, 1–25; Pierce 2005, 80–82).

In addition to its other functions, the ICT is designed to showcase public art that is financed through a privately funded endowment. In 2007, the CICF announced that it had commissioned Fred Wilson, a black conceptual artist, to create a piece of public art for the trail.4 His proposal, E Pluribus Unum, appropriated the African American figure on the Soldiers and Sailors Monument. Wilson's renderings depict the same man, his position now rotated so that he appears to be rising (fig. 3). His outstretched arm no longer reaches to a Caucasian goddess, and a banner representing the African Diaspora has replaced the broken shackles that he used to hold. The initial site for the sculpture was on city-owned property in front of a municipal government building. Wilson chose this site for its proximity to the Soldiers and Sailors Monument and its visibility (Labode 2012, 397). In his artist's statement, Wilson expressed hope that the artwork would provoke dialogue about race relations, history, and the nature of heroism.5 (Wilson, n.d.).

After the CICF approved his proposal, Wilson traveled to Indianapolis to speak with community members about his artistic practice and the ideas that informed E Pluribus Unum. Between February 2009 and October 2010, the CICF and the ICT held several open meetings in which they invited individuals across the city to learn more about Wilson and his project. Attendance at the meetings was modest. By September 2010, however, individuals and groups, most of whom were African American, began to publicly voice opposition to E Pluribus Unum. The project's detractors offered varied reasons for their resistance to Wilson's work. Some viewed the image itself as retrograde; in a widely circulated letter to the Indianapolis Recorder (Robinson 2010), the city's major African American newspaper, the writer asserted that the figure was "ape-ish" and compared E Pluribus Unum to a lawn jockey.6 Others argued that in a city with few representations of black people, replicating the freeman in Wilson's work did not present the unambiguously positive image of African Americans that they felt was needed. Many referred to E Pluribus Unum as a "slave sculpture" and argued that the work commemorated slavery, an era that should not be so memorialized. Opponents were also troubled by the proposed site for the sculpture: on a corner near a branch of the county jail and in front of a municipal building that houses, among other agencies, courts. Drawing a connection between slavery and the overrepresentation of African Americans in the penal system, protesters interpreted the presence of a "slave sculpture" as a cruel mockery. Others faulted the selection process as hierarchical, unable to accommodate public input, and ultimately undemocratic. Those opposing the work indicated that they had little interest in using the project as a focus for dialogue; they wanted the CICF to cancel the project.7

Although the proposed E Pluribus Unum generated significant discourse, it had not yet effectively fostered dialogue. In other words, many people were talking about the sculpture—some were even directly addressing issues related to art, race, and space—but the ideas circulated in the absence of reciprocal exchange. A public meeting in October 2010 was a turning point. After Wilson spoke, a group of people opposed to E Pluribus Unum effectively wrested control of the meeting from the moderator, who was posing questions that audience members had submitted on note cards, by speaking out of turn. They transformed the meeting into a session in which they forcefully advocated canceling the project. The heated tone of some of the exchanges convinced many—including those who had not been at the meeting—that public dialogue about the sculpture was impossible. 8

After this meeting, the CICF suspended the project. Over a year later, the agency convened four public meetings to discuss whether to proceed with the commission (McLaughlin 2011). In December 2011, the CICF announced that its board of directors had voted to cancel Wilson's commission, stating, "Over 90 percent of the participants [in the community conversations] were against the project" (Central Indiana Community Foundation 2011).

With E Pluribus Unum canceled, misconceptions flourished about the nature of the controversy and its racial politics. Wilson did not make a public statement. The media had reported the controversy in a diligent but superficial manner, so few people had access to the rationale of those who supported or opposed the artwork. Those who had hoped that the artwork would provide a platform for civic dialogue were also confounded.9 Some optimistically asserted that, even though the work would not exist, it had achieved Wilson's goal by allowing the public to engage with important issues of art and race (Gund 2012; Vetrocq 2011).10 People on all sides of the controversy concurred that the public meetings had not served as a space for the exchange of ideas raised by the work. They also agreed that Indianapolis needed to discuss its history of racial and class inequality, as well as the ways in which people participated in their city's government and cultural organizations. It was in this atmosphere that we proposed holding a symposium on some of the issues raised by the artwork.

Why a Symposium?

Organizing our campus–community conversation as a symposium, a particularly academic—and often hierarchical—form of discourse, may appear initially paradoxical. To the faculty members who developed the event, however, numerous factors made the symposium format appealing. First, we believed that it was important to contextualize theE Pluribus Unum project in the local and national landscape of racialized geographies and political and social power dynamics that had shaped the previous public debates. The controversy surrounding E Pluribus Unum raised a plethora of fascinating and difficult concepts, ranging from the nature of "community" to the ongoing legacies of slavery. We were concerned that ranging too widely would dilute the impact of the symposium and try the patience of many participants. Therefore, we focused on three concepts—art, race, and space—which were familiar to most people, foundational to the controversy, and often only receive superficial attention in public discourse. Further, a symposium, as a contained event, would provide valuable opportunities for students, especially those in the Museum Studies Program, to participate in a form of civic engagement. Finally, the university offered a venue that was not overtly aligned with any specific group of stakeholders.

While we were convinced of the value of the symposium format, we realized that it might be exclusionary and alienate members of the public, given the perceived disconnect between academic and community approaches to knowledge and the different vocabularies employed to talk about the cultural practices surrounding the E Pluribus Unum controversy. Further, because of scheduling difficulties, the symposium was slated to occur at the IUPUI campus on a Friday; we recognized that the weekday time would be an obstacle to many.

As we developed the symposium, we took care to address these challenges. We turned to colleagues at the university and museums for suggestions about how to foster an inclusive environment. These ideas continued to develop throughout the planning of the symposium, with input from moderators, students, and others who were committed to providing a space for discussion. We envisioned that the audience for the symposium could be wide, including students, academics, professionals working in museums and other cultural organizations, and interested members of the public. We alerted the ICT staff and those involved in the protests against E Pluribus Unum to our project. Although we invited representatives from these groups to attend, we decided that it was important to clearly articulate the symposium as a university-sponsored and university-organized event. In this way, delineating rather than blurring the line between campus and community allowed us to create a new forum for dialogue, a forum that was open to divergent views but that was at a spatial and temporal distance from the previous discourse about E Pluribus Unum.

Hybrid Structure, Varied Voices

The Art, Race, Space Symposium combined traditional academic components with formats more commonly employed in community forums, museum education initiatives, and student-centered learning environments. In addition to formal presentations from invited speakers, the symposium offered platforms for audience engagement that included personal reflection, face-to-face interaction, and virtual communication. In this section, we provide an overview of the symposium's structure and offer our analysis of these elements.

The symposium featured three sessions, each comprising three 30-minute presentations, followed by time for moderated discussion among the scholars and audience comments (fig. 4).11 Invited speakers shared a wide variety of perspectives, both disciplinary and ideological. Presenters included key players in the debate over E Pluribus Unum, as well as academics who specialized in anthropology, history, art history, architectural history, and visual culture. The symposium concluded with a round-table discussion that gave presenters and other attendees the opportunity to engage in small-group conversations related to the topics of the day.

Our first session offered an overview of the circumstances surrounding the E Pluribus Unum commission and the public debate that ensued. Rather than beginning with scholarly voices, the symposium started with a panel of nonacademic stakeholders. This approach allowed us to frame the day's conversations by first defining the terms of the debate that had prompted the symposium without creating a situation in which the speakers felt compelled to debate one another. In addition to providing attendees with a common starting point, it also established nonacademic expertise as a valid and significant voice in the conversation.

Fred Wilson opened the session with a presentation in which he shared examples of public art projects that he finds particularly compelling (fig. 5). Although this talk did not address E Pluribus Unum directly, it surveyed the professional creative context in which his proposal for E Pluribus Unum operated. Wilson's modest, insightful talk was important because it introduced audience members to the artist behind the canceled project. This was his first public appearance in Indianapolis since a public meeting in October 2010; his presence effectively reminded those in attendance that there was a human behind the accounts and rumors surrounding E Pluribus Unum. His talk also provided a valuable visual foundation for understanding the artist's work.

Next, Mindy Taylor Ross, curator of public art on the ICT, took the podium. Speaking publicly about the project for the first time since its cancellation, she offered an overview of the process of commissioning public art on the ICT in general, and E Pluribus Unum in particular. Ross laid out what she termed "just the facts" in an attempt to clear erroneous perceptions about the commissioning process. Amos Brown, a local radio personality, columnist, and outspoken critic of E Pluribus Unum, next spoke. Brown provided a rousing summary of the arguments that opponents of the sculpture project articulated. He averred that most of the people who protested did not oppose Wilson the person, but the process by which the art was selected. 12

The second session featured three professors whose research relates to the central themes that formed a historical and spatial context for the discourse surrounding E Pluribus Unum.13 Richard Pierce, a historian at the University of Notre Dame, contextualized the recent debates by offering insight into historical efforts of self-representation by Indianapolis's African American communities. He analyzed the city's twentieth-century political culture, in which African Americans attempted to negotiate with white power brokers for greater representation while maintaining hard-won material and legal gains. This strategy yielded mixed results and often left African Americans out of crucial political and economic decisions affecting their lives. Paul Mullins, a professor in the Anthropology Department at IUPUI, continued the exploration of the local context. Drawing on his long study of race, representation, and African American visibility in Indianapolis, he considered the remaining material traces of African American culture across the city and reminded his audience that the building in which we gathered was built on the site of a former African American neighborhood. By calling attention to the fraught landscape on which our symposium was held, Mullins demonstrated that scholars can be willing—sometimes eager—to question our own institutions to develop knowledge that can work for the benefit of a nonacademic public. Dell Upton, an architectural historian at the University of California, Los Angeles, spoke about his current study of public sculpture in the American South. His talk explored the interplay between racial politics and monuments dedicated either to Confederate soldiers or the Civil Rights era. He described a "dual heritage" discourse in which communities interpreted these monuments and memorials to vastly different eras as separate and equivalent, one for whites and the other for African Americans. Upton offered an opportunity for symposium participants to begin placing the Indianapolis experience into a broader, national context.

While our second panel drew scholars from a range of humanities-based disciplines, the third panel featured three art historians.14 Bridget Cooks of the University of California, Irvine, first analyzed other protests featuring African American representation, including the 1969 Harlem on My Mind exhibition, and described protesters' seizing the "opportunity to say no" as an assertion of self-definition and control. She then invited listeners to analyze E Pluribus Unum as they might have done had it actually existed and to consider the implications of its absence. Renée Ater of the University of Maryland expanded our conversation about race and public representation by exploring how those themes came together in a recent controversy surrounding a statue of Martin Luther King, Jr., in Rocky Mount, North Carolina. Her talk, like Upton's in the previous session, put the local case in perspective by exploring a related dispute in another contemporary community in the United States. Joining us from the University of Notre Dame, Erika Doss, who has published extensively on public art and public discourse in the United States, shared some of the key ideas and examples from her recent book Memorial Mania. Her analysis of the Clayton Jackson McGhie Memorial, which honors three men who were lynched in Duluth, Minnesota, demonstrated the ways in which a memorial to a painful history, in her words a "shameful" past, could become a place for contemporary healing and remembrance.

In the symposium setting, each speaker had time to share and develop her or his thoughts, uninterrupted. Collectively, the speakers' insights added depth to the local dialogue about E Pluribus Unum. They spoke about sophisticated ideas in an accessible way. Their performance demonstrated that scholars are indeed invested in public discourse: they use it in their research, they study how to make it more effective, and they participate in it themselves. By design, the symposium reinforced the power of dialogue with explicit directions, modeling, and participatory practices. Modupe Labode's opening remarks laid the charge to everyone in the room:

I'd like to share with you the challenges I've posed to myself for this symposium: to listen and speak openly and respectfully; to be patient; to engage in conversation about ideas with someone I meet here; to allow myself to be changed; and to take my experiences and do something with them.

The moderators and presenters similarly modeled active listening and engagement with one another. After each of the three sessions, the speakers returned to the stage and took questions from a moderator and from the audience. In response to the moderator's invitation to discuss what they had learned in the course of the symposium, presenters reflected on the campus–community interaction and the importance of scholarly and community discussions across disciplines. Paul Mullins explained: "Part of what I've been impressed by today […] is that the university has […] to create a welcoming environment to have these kinds of discussions" (Art, Race, Space: Moderated Discussion video 2013, 1:14). In response to Mullins's presentation, Renée Ater stated that

Paul's comments in his paper about the materiality of black subjectivity in the landscape was really important for me to hear today […] the way that you framed it […] made me really think about […] what happens when erasure in the landscape takes place. (Art, Race, Space: Moderated Discussion video 2013, 2:46)

Others expressed excitement that the symposium had attracted such a large audience of people who dedicated their Friday to thinking about public art (Art, Race, Space: Moderated Discussion video 2013, Cooks, 7:46, Doss, 11:48). Mindy Taylor Ross noted, "The biggest fear that I had being a member of this community" was "that the cancellation of the project was in fact a way to not have this conversation" (Art, Race, Space: Moderated Discussion video 2013, 17:25). She hoped that such conversations would continue.

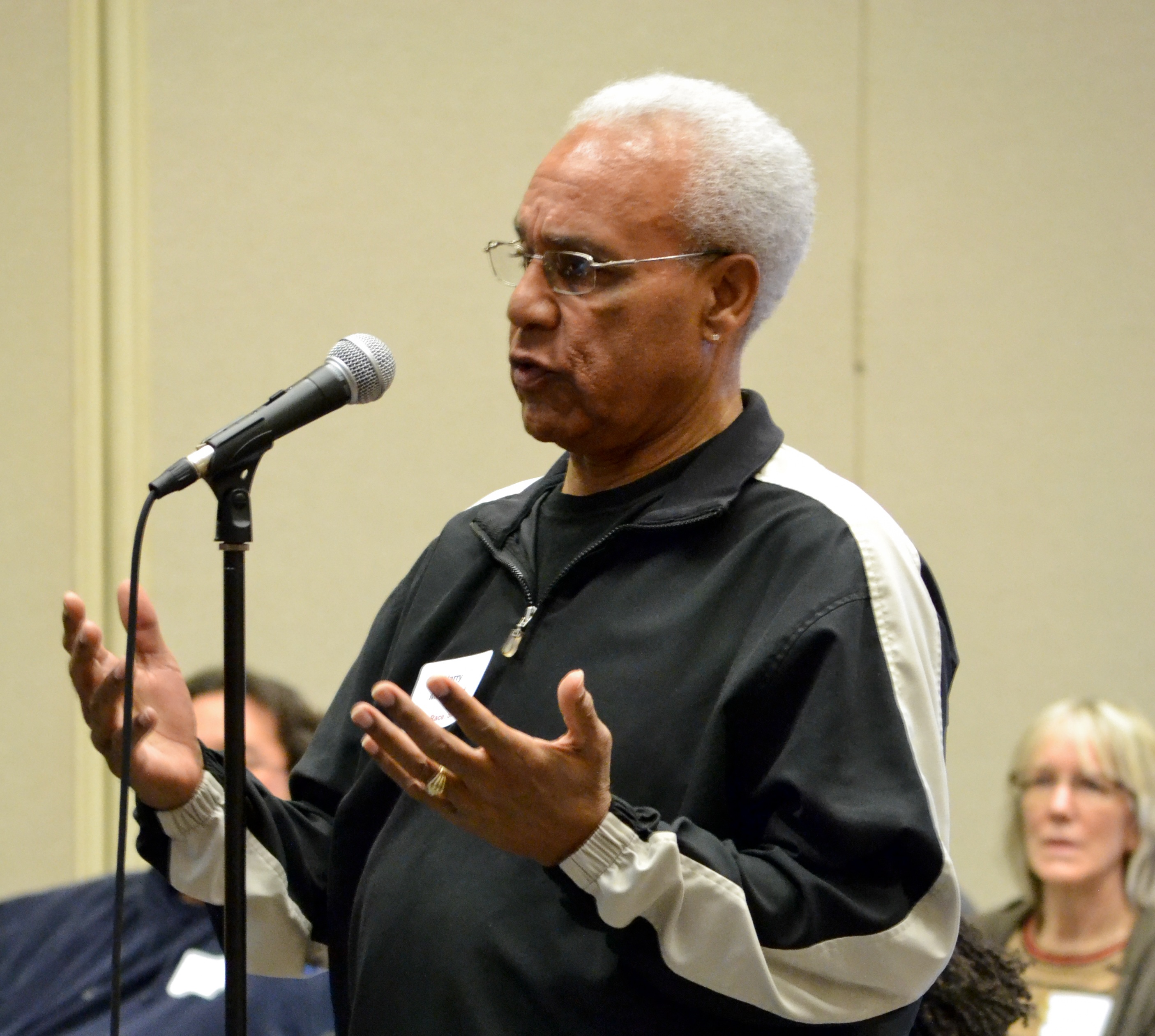

Audience members also modeled respectful and active engagement that reinforced the expectations of civil conversation. During the discussion period following each set of presenters, people came to an open microphone in the center aisle to pose questions, offer reflections, and share experiences, often including why they supported or opposed E Pluribus Unum (fig. 6). People articulated ideas and perspectives that many of those in attendance either had not heard before or had encountered only in distorted forms in the media. One audience member stated that, in his opinion, the process of public art was flawed because "those that are making decisions [about public art] are not culturally competent, meaning that they many not consider other cultures. They see it one way" (Art, Race, Space: Moderated Discussion video 2013, 45:41). Others debated issues of aesthetics, form, artistic craft, and their relationship to the representational and ideological import of the art. Strongly held views were both expressed and heard. Wilson affirmed the value of this kind of candid exchange, stating that intense and deliberate community conversation should occur before public art was selected and that this "dialogue should be so important to the project that what comes out is a reflection of those values and understanding" (Art, Race, Space: Moderated Discussion video 2013, 46:18).

In addition to the traditional academic format of formal presentations delivered from a lectern, we also built the day around a number of informal learning and dialogue activities that we adapted from our experiences with classroom teaching and museum public programs. We complemented question-and-answer sessions, which implicitly position the respondents on stage as powerful experts, with a session of small-group conversations. In a second conference room, we arranged tables that seat approximately ten people each. After the third panel session concluded, we invited symposium attendees and presenters to join us in this adjacent room for round-table discussions. Rather than assigning group numbers to attendees as we might have done in a classroom, we encouraged participants to select their own seats. At each table, participants found one or two discussion prompts such as, "Should public art raise issues/provoke discussion or simply beautify?" or "Do you feel included in the target audience for public art in this city? Why or why not?" These conversations brought out an exchange of thoughtful ideas that we had not previously observed during the E Pluribus Unum controversy. For example, a person in one group articulated a challenging intraracial dynamic at work in the controversy:

I'm not offended by that art at all. It doesn't offend me, but yet I don't want to defend Mr. Wilson because I don't want to offend my African-American people. So my question is, does that make me a racist or a coward? I don't know. (Art, Race, Space video transcript 2013)

A different participant discussed the importance of process in public art, noting that "process is probably equally if not more important than the final product in some cases" (Art, Race, Space video transcript 2013). Perhaps participants felt able to speak candidly because they were in small groups, had shared the common experience of the symposium, or simply felt comfortable with one another. At the very least, the difference between these comments and the tenor of the earlier contentious public gatherings suggests that productive dialogue requires more than simply inviting people to speak at meetings.

In the final session, a local museum professional invited the small groups to share their discussions with the symposium audience. One man noted that his group believed that Indianapolis needed more open discussion. To expand on his point, he shared some of his group participants' observations about the role and limitations of art: "Art is one thing, but to deal with the whole idea of racism and white supremacy, art can't do it by itself. But it certainly can help with some parts of the community as far as self-esteem, and that's important" (Art, Race, Space: Closing Remarks video 2013, 2:38). Although a comment like this one might appear straightforward, it included important observations that had been overlooked during the years of discourse.

We recognized that some participants might be uncomfortable about publicly expressing their ideas about art, race, and space by posing a question to panelists or speaking with the members of their small discussion group. To encourage these individuals to add their thoughts to the conversation, we included sticky notes and a pen in every participant's registration folder. We positioned flip boards around the main conference room and invited attendees to share their thoughts (anonymously, if they preferred) by writing notes and posting them on a board throughout the day. Fewer people took advantage of this component of the symposium than we had anticipated. Perhaps more people would have posted ideas if the boards were in the hall with the refreshments instead of the same room in which the presenters spoke. A different location may have given individuals the anonymity, space, and time to compose their thoughts.

Another symposium feature used social media to reach beyond the physical and temporal boundaries of the event. People who wanted to engage in dialogue with others during the presentations, either from the audience or from afar, could take advantage of the hashtag (#ArtRaceSpace) that we developed for the event. Three volunteers from the Museum Studies graduate program (two current students and one alumna) tweeted live during the symposium from the handle @ArtRaceSpace. They shared interesting snippets from presentations, as well as questions and comments from audience members. The volunteers specialized in various disciplines—anthropology, history, public culture, material culture, social media, and art history. One had followed the debate over E Pluribus Unum closely while working as a research assistant for one of the authors. Their interdisciplinary expertise allowed them to understand the significance of what they were hearing and compose informative tweets (Hayde 2013). Through the website, the registration folder, and announcements, we invited symposium attendees and those who were unable to join the event in person to follow along or to share their thoughts on Twitter.15

Although Twitter offered a platform for visualizing and recording the discourse that the symposium generated, it has limitations, most obviously the text limit of 140 characters per tweet. Further, as one of the volunteers observed, Twitter users, navigating content from a variety of sources and in turn generating their own material, might not be able or willing to engage in debate. One indicated that she felt constrained from participating in the dialogue because of her position as a symposium volunteer:

I felt very self-aware at the conference as a representative of the IUPUI museum studies program and as a participant in the EPU project. Even when I was tweeting from my personal account I felt hesitant to disagree or challenge ideas of the presenters and audience members. I can remember a key instance where I felt like one of the presenters was relying on heavy generalizations to get a rise out of the crowd, and I wanted to call him out for resorting to such tactics to make a point. But I refrained from doing so, instead searching for other audience reactions to retweet.

She concluded, "I felt like we were more 'record keepers' than 'conversation starters' or 'mediators.'" 16

The Twitter volunteers encountered philosophical issues of communication and authority. They quickly debated whether they should preserve the speaker's words, even when the presenter employed academic or arts management jargon, or convey the speaker's intent. The volunteers engaged in extemporaneous discourse analysis as they negotiated how people employed complex terms. One volunteer noted that

even as people both on the stage and in the audience frequently problematized the sometimes overlapping yet distinct meanings of "public art," "memorials," and "monuments," they elided organizations with the individuals representing them […] and referred to images in ways they (not always correctly) assumed were shared […] the variety of ways people described the figure on the Soldiers and Sailors Monument (e.g., "Freedman," "freed slave," "slave image," etc.) really stood out to me and I found myself unsure of how to describe the figure as the "official" online voice of the symposium. 17

While fully cognizant of the limitations of the medium, the volunteers agreed that Twitter was both a valuable form of public dialogue and a record of the symposium, which "could be useful in any context."18 Their comments support observations that the role of social media in promoting access and dialogue is still uncertain (Wong 2012).

Overall, the symposium provided a balance between the researched, theorized, and well-argued positions of the scholars and the experiences, activism, and community-based knowledge of other speakers and many in the audience. The structure guided the exploration of intertwined issues but also provided an opportunity for symposium participants to digest and debate the presenters' arguments. The panels also made connections between disciplines, issues, and places in a way that may have diffused some of the frictions that many have associated with any discussion of E Pluribus Unum.

By blending formal presentations with other opportunities for interaction, we fostered a constructive dialogue among scholars and community members, and across those groups. Community members could experience how the analytical tools of the humanities positioned their experiences and ideas in a larger context. The emphasis placed on interdisciplinarity and the emphasis placed on dialogue among presenters and with the audience facilitated a productive exchange of divergent ideas. One speaker commented that the symposium had been one of the most intellectually stimulating she had been to in years. Presenters also expressed that the range of voices gave them a new appreciation for the cultural and political dynamics that went beyond the media reports of the controversy. The student volunteers whose work supported the symposium experienced the intensity that is often a part of dialogues between the campus and community.

The symposium was an intervention in an ongoing process of understanding the E Pluribus Unum controversy. Neither the organizers, nor the presenters, nor the attendees assumed that the symposium would somehow resolve the underlying issues. Individuals expressed strong opinions; revealed pain, anger, or resentment; and engaged in discussions with others who were situated differently in the debate over the artwork. Many were willing to engage in a dialogue and listen, with the expectation that they, too, would also be heard. Without this engagement from presenters and members of the public, who evinced their willingness to engage with the hybrid forms of discourse, the symposium would have been far less compelling.

Although it is too early to determine precisely how the dialogues that occurred at the symposium will ultimately impact interpretations of art, race, and space in Indianapolis (or farther afield), the symposium set a valuable precedent for future conversations. As scholars committed to civic engagement, we believe that we have a responsibility to create and preserve archives of this significant event. Publishing this article about the symposium's hybrid structure is one component of that effort. Another is harvesting the Twitter feed and making it available to the public. We will preserve that and other recordings of the event on our publicly accessible project website. We are also preparing dialogue kits using prompts similar to those employed in the round-table discussion, which teachers and community members may use to continue engaging with issues of art, race, and space in other venues. In each of these ways, we expect to expand the symposium's practice of facilitating and promoting hybrid discourse. The Art, Race, Space Symposium demonstrates that universities that accept their legacy of both privilege and power can also harness their resources to foster a safe space in which a broad range of constituents can explore complex and contentious issues. Universities can bring together humanities scholarship and community expertise to create knowledge that has public value and relevance.

The Art, Race, Space Symposium was funded by a grant from the IUPUI Arts and Humanities Institute.

Works Cited

Art, Race, Space: Closing Remarks (video). 2013, January 25. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b_5t93HYqhI&list=PLaB-5LB3XNNbykHHp-ED_QW44g_KnsX4E.

Art, Race, Space: Moderated Discussion (video). 2013, January 25. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RCrprxAFyD0&list=PLaB-5LB3XNNbykHHp-ED_QW44g_KnsX4E&index=8.

Art, Race, Space (video transcript). 2013. Indianapolis, IN: IUPUI Museum Studies Program.

Ater Renée. 2011. Remaking Race and History: The Sculpture of Meta Warrick Fuller. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Bartner, Amy. 2010. "Sculptor, Crowd Face Off at Meeting." Indianapolis Star, October 20.

Brown, Amos. 2010. "Raging Emotions and Passions over Black Images on the Cultural Trail." Indianapolis Recorder, October 1.

Central Indiana Community Foundation. 2011, December 15. "Brian Payne's Remarks from Announcement of Fred Wilson Public Art Project." http://www.cicf.org/cicf-news/2011/december/brian- paynes-remarks.

"Citizens Protest Slave Image." 2011. Indianapolis Recorder, August 5, B8.

Cooks, Bridget R. 2011. Exhibiting Blackness: African Americans and the American Art Museum. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press.

Doss, Erika. 2010. Memorial Mania: Public Feeling in America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Finkelpearl, Tom. 2000. Dialogues in Public Art. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Globus, Doro, ed. 2011. Fred Wilson: A Critical Reader. London: Ridinghouse.

González, Jennifer. 2008. Subject to Display: Reframing Race in Contemporary Installation Ar. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Gray, Ralph. 2003. IUPUI—the Making of an Urban University. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Green, Tyler. Modern Arts Notes blog, retrieved from: http://blogs.artinfo.com/modernartnotes/category/e-pluribus-unum/.

Gund, Agnes. 2012. "Art and Argument." Huffington Post, August 9.http://www.huffingtonpost.com/agnes-gund/public-art-and-argument_b_1761239.html?ncid=edlinkusaolp00000003;

Kramer, Jane. 1992. "Whose Art Is It?" New Yorker, December 21.

Labode, Modupe. 2012. "Unsafe Ideas, Public Art, and E Pluribus Unum: An Interview with Fred Wilson." Indiana Magazine of History 108: 383–401.

Lindquist, David. 2010. "Artist Hopes His Work Will Spur Questions." Indianapolis Star, April 12, A11;

McLaughlin, Kathleen. 2011. "Decision Nears on Fate of Freed-Slave Sculpture." Indiana Business Journal, October 7. Mikulay, Jenny. 2011. "Speaking of Influence: A Monument's Invisible Man." Art 21 (blog), February 22. http://blog.art21.org/2011/02/22/speaking-of-influence-a-monument%E2%80%99s-invisible-man/.Mullins, Paul. 2011. Archaeology of Consumer Culture. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

——2003. "Engagement and the Color Line: Race, Renewal, and Public Archaeology in the Urban Midwest." Urban Anthropology 32 (2): 1–25.

Murray, Freeman and Henry Morris. 1916. Emancipation and the Freed in American Sculpture: A Study in Interpretation. Washington, DC: printed by author.

Penner, Diana. 2006. "$15m Gift Paves Way for Trail." Indianapolis Star, October 13.

Pierce, Richard. 2005. Polite Protest: The Political Economy of Race in Indianapolis,1970. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Robinson, Leroy. 2010. Letter to the editor. Indianapolis Recorder, September 20.

Rosenberg, Tracy Jean. 2011. "History Museums and Social Cohesion: Building Identity, Bridging Communities, and Addressing Difficult Issues." Peabody Journal of Education 86: 115–128.

Saahir, Michael, and Donna Stokes-Lucas. 2011. "Sculpture Doesn't Belong on Public Property," Indianapolis Star, August 7.

Savage, Kirk. 1997. Standing Soldiers, Kneeling Slaves: Race, War, and Monument in Nineteenth-Century America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.Scurch, Thomas W. 1994. "Mile Square." In Encyclopedia of Indianapolis, edited by David J. Bodenhamer and Robert G. Barrows, 1007–1008. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Ševčenko, Liz. 2010. "Sites of Conscience: New Approaches to Conflicted Memory." Museum International 62: 20–25.

Upton, Dell. 2008. Another City: Urban Life and Urban Spaces in the New American Republic. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. Vetrocq, Maria. 2011. "Was the Cancellation of Fred Wilson's Indianapolis Project Really a Confirmation of His Principles?" December 21. Artinfo.com. http://www.artinfo.com/news/story/754477/was-the-cancellation-of-fred-wilson%E2%80%99s-indianapolis-project-really-a-confirmation-of-his-principles. Wong, Amelia. 2012. "Social Media towards Social Change: Potential and Challenges for Museums." In Museums, Equality and Social Justice, edited by Richard Sandell and Eithne Nightingale, 281–293. London: Routledge.Notes

1 For the historic context of the kneeling African American as a representative of Emancipation, see Savage (1997). There is little evidence that early twentieth-century Indianapolis residents found the freeman figure on the Soldiers and Sailors Monument remarkable. The important exception is the critique in Murray (1916, 125–28).

2 For public art on the Indianapolis Cultural Trail, see the organization's website, http://www.indyculturaltrail.org/publicart.html, accessed February 14, 2013. For the Indianapolis Cultural Trail's website on Fred Wilson's E Pluribus Unum, see FredWilsonIndy.org, http://www.fredwilsonindy.org/, accessed February 14, 2013.

3 The initial symposium planners included Elizabeth Kryder-Reid, associate professor, anthropology and museum studies and director of the Museum Studies Program; Modupe Labode, assistant professor, history and museum studies and public scholar of African American history and museums; Paul Mullins, professor and chair of the Anthropology Department; and Owen Dwyer, associate professor of geography. Laura Holzman, assistant professor, art history and museum studies and public scholar of curatorial practices and visual art, joined the symposium planning group in August 2012.

4 Fred Wilson has exhibited his work widely since the 1980s, has received a MacArthur Foundation Award, and he represented the United States at the Venice Biennale in 2003. His work in museums and historic sites, of which Mining the Museum is particularly well known, often engages with institutionalized or unseen racism, including the ongoing legacy of slavery. For an overview of criticism and interviews, see Globus (2011) and González (2008, chap. 2).

5 Wilson, Fred. n.d. ca. 2007. "Artist's Statement: E Pluribus Unum." In possession of authors.

6 One group, Citizens Against the Slave Image, organized lectures and protests against the work, including an "anti-slave" rally on July 30, 2011. See "Citizens Protest Slave Image" (2011, B8) and Saahir and Stokes-Lucas (2011); an online petition against E Pluribus Unum is posted at http://1slave-enough.wix.com/inindy, accessed February 14, 2013.

7 For representative media coverage, see Lindquist (2010, A11), Brown (2010, A10), and Green (2013). It appears that, until learning of Wilson's proposal, many in Indianapolis were unaware of the figure of the freed man (Mikulay 2011).

8 For example, when Wilson noted that it was impossible to change the art at this point because "It's been birthed," someone in the audience replied, "It can be aborted" (Bartner 2010, 2).

9 In other instances, such as Richard Serra's Tilted Arc and John Ahearn's work for the South Bronx Sculpture Park, the controversies that resulted in the works' removal began after public installation (Kramer 1992, 80–109; Finkelpearl 2000, 60–109).

10 Wilson's response to this suggestion is more nuanced (Labode 2012, 397–99).

11 The "Art, Race, Space" website includes archives of the symposium, resources, and curriculum materials: http://liberalarts.iupui.edu/artracespace/, accessed February 14, 2013. On the basis of similar events at IUPUI, we had initially been prepared for fewer than 100 people to register for the symposium. On January 24, 2013, the day before the symposium, 200 people had registered online. We estimate that about 160 people actually attended, despite the snowy weather.

12 Amos Brown consistently covered the developments of E Pluribus Unum. For examples from his radio show Afternoons with Amos, listen to "Amos Interviews Fred Wilson, Designer of Cultural Trail 'Slave' Statue," October 20, 2010, http://praiseindy.com/434401/audio-amos-interviews-fred-wilson-designer-of-cultural-trail-slave-statue/; "Controversial Statue Project Gets $50K Joyce Awards Grant," January 26, 2011, http://praiseindy.com/1109161/controversial-statue-project-gets-50k-joyce-awards-grant/; "'Slave Statue' Project Stopped; Community Input Sought for Public Art," December 13, 2011, http://praiseindy.com/1566031/slave-statue-project-stopped-community-input-sought-for-public-art/.

13 For representative scholarship of these scholars, see Mullins (2011) and Pierce (2005) .

14 For representative work of these scholars, see Ater (2011), Cooks (2011), and Doss (2010).

15 We estimate that 330 tweets were exchanged using the #ArtRaceSpace hashtag.

16 E-mail message from Maggie Schmidt to Modupe Labode, February 11, 2013.

17 E-mail message from Dolly Hayde to Modupe Labode, February 12, 2013.

18 E-mail message from Maggie Schmidt to Modupe Labode, February 11, 2013.