Laura Browder and Patricia Herrera

Overview: Building an Archive

A couple of years ago, as we were putting together a documentary theater course on civil rights and education in Richmond, we got to know a local man named Mark Person, whose name we had run across in a book about school desegregation in Richmond, The Color of Our Skin (Pratt 1993). Mark, who is white, told us a story about how his family came to own Nat Turner's bible, after Turner had been baptized in the millpond of the Person United Methodist Church, a family church Mark still attends. For Mark, this bible was more than a historical artifact—it was a metaphor for how he thinks about the history of race in America. Mark was on the verge of sharing this family treasure with a wider audience as a way, perhaps, of inspiring dialogue about the relationships between whites and blacks. Through his tireless efforts to interest community members in our project, Mark became instrumental in the success of our documentary theater production. More than that, he offered us a new way to think about archives—not just as repositories but also as active agents in the process of creating a dialogic community history of civil rights in our city.

We saw our community-based course, Massive Resistance: A Documentary Theater Project, as a way to use theater to teach our students about the rich and complex history of Richmond's educational system, fraught by the legacy of segregation, desegregation, and resegregation. Our students took on different roles—playwrights, ethnographers, actors, archivists, researchers, oral historians, documentary makers, community advocates, and facilitators. The wealth of material they gathered through archival research and interviews, in preparation for collaboratively writing and performing their play, led us to want to create a digital archive that would live on and provide material for future courses.

What we only slowly realized, in working on this digital archive—"The Fight for Knowledge: Civil Rights and Education in Richmond, Virginia"—was that the process of building the archive could help us reconceptualize the relationship between archive and theater—and help us enrich our thinking about both archive creation and documentary theater practices. Elsewhere, we have written about the fruits and challenges of our documentary theater project as an educational endeavor for our students (Browder and Herrera 2012). But here we want to talk about the residue of this course—the multiple archives that have grown out of this project, and the way this has led us to propose a new way of thinking about archives.

Archive-building, and the creation of the community-based learning (CBL) course from which we developed this archive, both require many things, not least a tremendous amount of institutional support. It is not news that many truly worthwhile community-based projects cannot be fully implemented without a high level of fiscal support; we are fortunate enough to be based at a university that sees engagement with the city as central to its mission. In our case, this support is allowing us to team-teach a small course each year for five years and has funded a doctoral fellow for two of those years to design and build our digital archive. The university has also recognized the contributions of our community partners through honoraria, when appropriate.

On a number of levels, this project would never have been possible without the help of the university, most specifically the Bonner Center for Civic Engagement (CCE). Like a number of sophisticated university-based civic engagement centers, the CCE has moved far beyond the model of service learning to focus on, as its mission statement proclaims, "Transforming student learning. Deepening faculty engagement. Partnering with the community to address identified needs," with the aim of "fostering social responsibility in our students and preparing them to lead lives of purpose." These are laudable goals but not unusual in the world of civic engagement programs. One of the distinctive features of our CCE is its faculty fellow program, which provides a stipend for faculty members across the university to gather first for a few days in the summer, and then for a day each month the following year, to develop and implement CBL courses. As fellows, we were able to exchange ideas with a group of faculty from accounting, geography, education, psychology, and the digital scholarship lab, colleagues who proposed to engage their students in the community in a wide range of ways—from volunteering in community organizations to bringing community speakers into the classroom to embarking on study trips.

As part of our fellowship program, we met with different community organizations willing to work with faculty. One of these was Henderson Middle School, an all-black public school whose Communities in Schools site coordinator, Rosemarie Wiegandt, became an important member of the project team. We also reached out to organizations already familiar to us—the racial reconciliation group Hope in the Cities, the Library of Virginia, and special collections at Virginia Commonwealth University's library. The openness and willingness of all of these organizations—facilitated by the reputation in Richmond of both the university and the CCE—helped us keep pushing the boundaries of our course.

The CCE faculty fellowship program made it possible for us to take our course far beyond what we had originally envisioned. What made this program transformative for us was a combination of the practical linkages we were able to form with community partners and the kind of visionary questions that CCE leaders were posing about how to push community-based learning to a new level. At the core of these questions was, how can we as educators help change the relationship of the university to the community? While much of what we learned in the group was practical, the most important question we took away was both philosophical and ethical. One of the conversations that proved most influential in our thinking was about using community knowledge to build academic learning, through a circular model of knowledge flow from community to university and back again. In other words, once our students had amassed knowledge from their community-based research, how would it serve the community? By the end of our first semester teaching the course and participating in the faculty fellows discussion group, we had realized how profoundly our community partners had shaped our course and our approach to studying Richmond history.

Influenced by the CCE's focus on building long-term relationships, we set out to develop a course that would not only go beyond the classroom (like many university–community collaborations) but that would strengthen existing relationships, spawn new collaborations, and initiate related projects that could continue for years to come. We created "The Fight for Knowledge," a digital archive in partnership with area museums and a university library. The class also inspired us to work on new projects: a city-sponsored oral history, photography and sound project about the history of Richmond's bus drivers, a collaborative oral history and photography project with a South African photographer and the VCU Anderson Gallery, and a play that the two of us will write next year for University of Richmond theater and beyond, based on our oral history transcripts from interviews that we've conducted. We wanted our class not only to create art and make meaning of history but also to create a wide range of opportunities for future community engagement and art making. Most of all, we were curious about how far, and in how many media, we could expand this opportunity for understanding the history of race and racism in Richmond.

Why Documentary Theater?

At the foundation of this course was our shared interest in documentary theater. For us, a documentary theater production was a way for our students to give back to the community what its members had shared with them. After all, documentary theater has throughout its history been grounded in questions of citizenship and community building. With its origins in Bolshevik agit-prop (agitation and propaganda), its wildly successful adaptation by the federal government during the Great Depression, its transformation during the 1960s to a focus on personal testimonials, and most recently its productions on Broadway and off-Broadway stages, for nearly a century documentary theater has provided a way for citizens to engage in the social issues of their day.

Documentary theater had its genesis in the living newspapers of the Soviet Union during the 1920s, which sought through performance to bring the news and propaganda of the day to a largely illiterate population. Later, this form spread to the workers' theater of Germany and then appeared in the United States as the living newspapers produced under the auspices of the New Deal–era Federal Theater Project (1935–1939). Borrowing from the overtly agit-prop dramas of the Soviet Union, these productions addressed significant political and economic issues of the day, such as housing shortages and deforestation. All of these plays presented facts—culled from official or government documents and newspaper reporting—in a theatrical context, offering audiences a way to understand their current reality in light of history and economics.

The 1960s and 1970s were a transitional period for documentary theater. The form moved from a focus on impersonal public documents to publicly available personal accounts. Some of the most powerful examples of this type of theater include Martin Duberman's In White America: A Documentary Play (1963), which drew upon letters, speeches, journals, songs, and personal accounts from a range of historical figures, including the famous, such as Booker T. Washington, as well as less known figures: a member of the Ku Klux Klan, an escaped slave, a black teenager integrating a public school in Little Rock, Arkansas, in 1954. Duberman's play relies heavily on archival sources, but unlike those used by the living newspaper writers of the Federal Theatre Project, these sources bring human voices from the past to life.

Similarly, although in a more tightly focused way, Eric Bentley's Are You Now or Have You Ever Been: The Investigations of Show-Business by the Un-American Activities Committee 1947–1958 (1972) was based on the transcripts of House Committee on Un-American Activities investigations of left-wing activity, culled from his anthology Thirty Years of Treason. While some of the trials highlighted in his play had already been televised, many of the transcripts were difficult to access. Thus, while the events of the play had been public at the time of their occurrence, they had been lost to later generations. Bentley's task was to insert these voices back into public consciousness.

Most documentary theater of this period was undergoing a shift from relying on official documents, such as the Congressional Record, to building on personal accounts of historical events, still culled from official archival sources; toward ultimately creating and then performing hitherto unheard accounts elicited directly by the playwright or creative team. This represents a profound political shift. In the new paradigm, personal experience, narrated directly to the creators of documentary drama, seems to be more "true" and valued more than that which comes from archival sources. The new paradigm stresses the playwright's proximity to the moment of revelation and to the emotional truth of that revelation.

This is a major departure from earlier approaches to documentary theater. In the 1930s, the instruction manual for playwrights working on the Federal Theatre Project's Living Newspapers cautioned that

authenticity should be the guiding principle in Living Newspaper production . . . some of the most fascinating and also dramatic statements are to be found in the daily columns of the press. Assemble a wide, firm foundation of factual material and upon this can be built the architecture of good theater. (Federal Theatre Project, n.d., 2–3)

By the 1980s, documentary theater-making had moved toward a valorization of the human exchange between interviewer and interviewee, with the drama coming not from the interplay of historical forces but from the impact of historical events upon the emotional lives of individuals.

Interview-based documentary drama gained popular attention in the late 1980s, after Anna Deavere Smith visited communities in the wake of social traumas (such as the Crown Heights and Los Angeles riots) to interview a wide range of subjects, stitching their words together to create theatrical solo performances. Smith works to perfectly reproduce the words, pauses, and gestures of each interviewee, including commentators not present during the events. The documentary performance is based on personal perspectives rather than official documentation or statistical data.

Documentary theater today is still used to reframe history and expose social injustices. In The Exonerated (2000), playwrights Jessica Blank and Eric Jensen used interview transcripts with death row inmates who had been exonerated of their crimes to create a drama that questioned the use of the death penalty and sparked public conversation about this issue. Another notable example of documentary theater in this period is The Laramie Project (2000), a play about the murder of college student Matthew Shepard, created by Moisés Kaufman and members of the Tectonic Theater Project. This play was based on interviews by ensemble members of Laramie residents in the wake of the tragedy (Dawson 1999; Martin 2010).

We wanted to draw upon all of these traditions but also focus on the interplay between personal testimonies and other forms of historical documentation. Both The Laramie Project and Smith's repertoire center on discrete, dramatic incidents in the life of a city or town, seen through interviews with residents; our approach, by contrast, creates a conversation between the city's archives and the living memories of its citizens—a conversation about events that may still be taking place, like segregation, desegregation, and resegregation.

Unlike The Laramie Project and Smith's work about the Los Angeles and Crown Heights riots, which dealt with recent traumas, our project was to open a conversation about an old wound that has never healed and that festers to this day. Our students would conduct archival and library research, interview community members, and collaboratively create a performance piece about real or semi-real events. Our hope was to inspire critical questions about history, memory, and justice. We wanted to make sense of the lived experience of interviewees through archival materials and make sense of archival materials in the context of personal history.

The tension created within the mutual flow of knowledge from the lived experience to the archive and back again fuels the engine of our documentary theater approach. What would The Laramie Project have looked like if it had used newspaper articles, textbooks, and other materials documenting the previous century of homosexuality and homophobia in Wyoming? What would Twilight: Los Angeles have been if it had incorporated the documentary record of police harassment and urban renewal projects in that city? These questions are not meant to diminish the extraordinary qualities of these works but rather to explore what kinds of histories can be told when different archival forms speak to each other. It is also a way to honor the achievements of those documentary theater pioneers who created works that stirred millions to reconsider the crises of their nation.

Collaborative Archive-Building

The semester passed in a blur of archival field trips, racially charged moments in the classroom, and difficult and eye-opening interviews with community members, all of which our students massaged into their collaborative performance piece. On the night of the show, we experienced a strange kind of prenostalgia as we watched our students enact the drama they had built on these materials, a performance that evaporated as we watched it, as all performances must. We listened as our postperformance panelists recalled their experiences of desegregation and as people came up to us afterward wanting to talk more about Richmond's history of civil rights and education. There had to be a way, we thought, to preserve some of this material in one place—and, importantly, to develop an archive that could continue this discussion with students, community members, teachers, and scholars.

What would a community archive mean? How could we use new technologies, materials, and spaces, both digital and actual, to create a living archive—one that could capture the ephemeral nature of performance, memory, and history by not just collecting objects from the past but also including the stories of those objects' owners as they looked back over a distance of decades? We wanted an archive that would constantly bring past and present, memories and current conflicts and dreams, into dialogue with one another. And we wanted an archive that would be shaped by community needs—in this case, the need to collect the scattered materials of a pivotal time in the lives of many Richmonders who participated in desegregation.

Clearly, this undertaking would require the skills and vision of many collaborators—a digital archive-building team. We first invited Salvador Barajas, a PhD candidate at VCU who had expertise both as a digital archivist and as a sound artist, and whose dissertation involved creating a digital archive about his small southwest Virginia town, which was being transformed by Latino immigrants in the wake of NAFTA. He came to the University of Richmond as a two-year doctoral fellow. We thought we could learn a lot from his expertise in creating community-centered digital archives that are sensitive to the needs of groups that are not always technologically savvy. He created the digital archive "The Fight for Knowledge" as well as recorded the oral history interviews of our students (http://thefightforknowledge.org/).

Katherine Schmidt, a student in the class, had been moved by what she heard from Henderson Middle School students when our class performed scenes from our play there. She wanted to continue the volunteer work she had been doing with Henderson students—but to focus this work on creating an archive of their experiences with segregation in the schools. By including their work in our archive, we hoped to provide them with a way to contextualize the segregation they encountered in their daily lives. It was important to us that this archive be cross-generational in both its production and in its audience. Kelsey Mickelson, another student from that year, created a video that documented University of Richmond students' experience in creating the first year's drama. (Digital stories created by students from Henderson Middle School and the University of Richmond can be found at (http://thefightforknowledge.org/digital-stories).

Connor Dolson was a senior at Bennington College working on a thesis about education and civil rights in Virginia. Contributing to the digital archive by developing lesson plans for high school teachers built on his research interests (http://www.thefightforknowledge.org/additional-resources). We plan to implement Connor's lesson plan in the next iteration of our course, working with a local high school teacher, another way to extend the project beyond its original boundaries.

Finally, we contacted Wesley Chenault, whom VCU had just hired as the new Special Collections and Archives director. He was not only an archivist interested in civil rights history, but also a performer, a member of the collective John Q (http://johnq.org/), which performs queer histories of the South that have been hidden from public memory. Wesley was intrigued by the possibility of linking VCU's substantial holdings in local African American history to our new digital archive. Wesley wanted to build the university's oral history holdings and proposed we create an oral history bank of interviews from our documentary theater project, make it accessible to people, and in the process strengthen our ties to VCU. As it turned out, he and his colleague Yuki Hibben also helped us think about the multiple ways archives are both created and used—how we could not just bring the public to the archive, but bring the archive to the public. One of our ideas is to exhibit the archive we created of Wythe High School, which had been all white and then through busing became almost all black. We then hope to record memories of alums who view this exhibition.

From a Digital Archive to a Living Archive

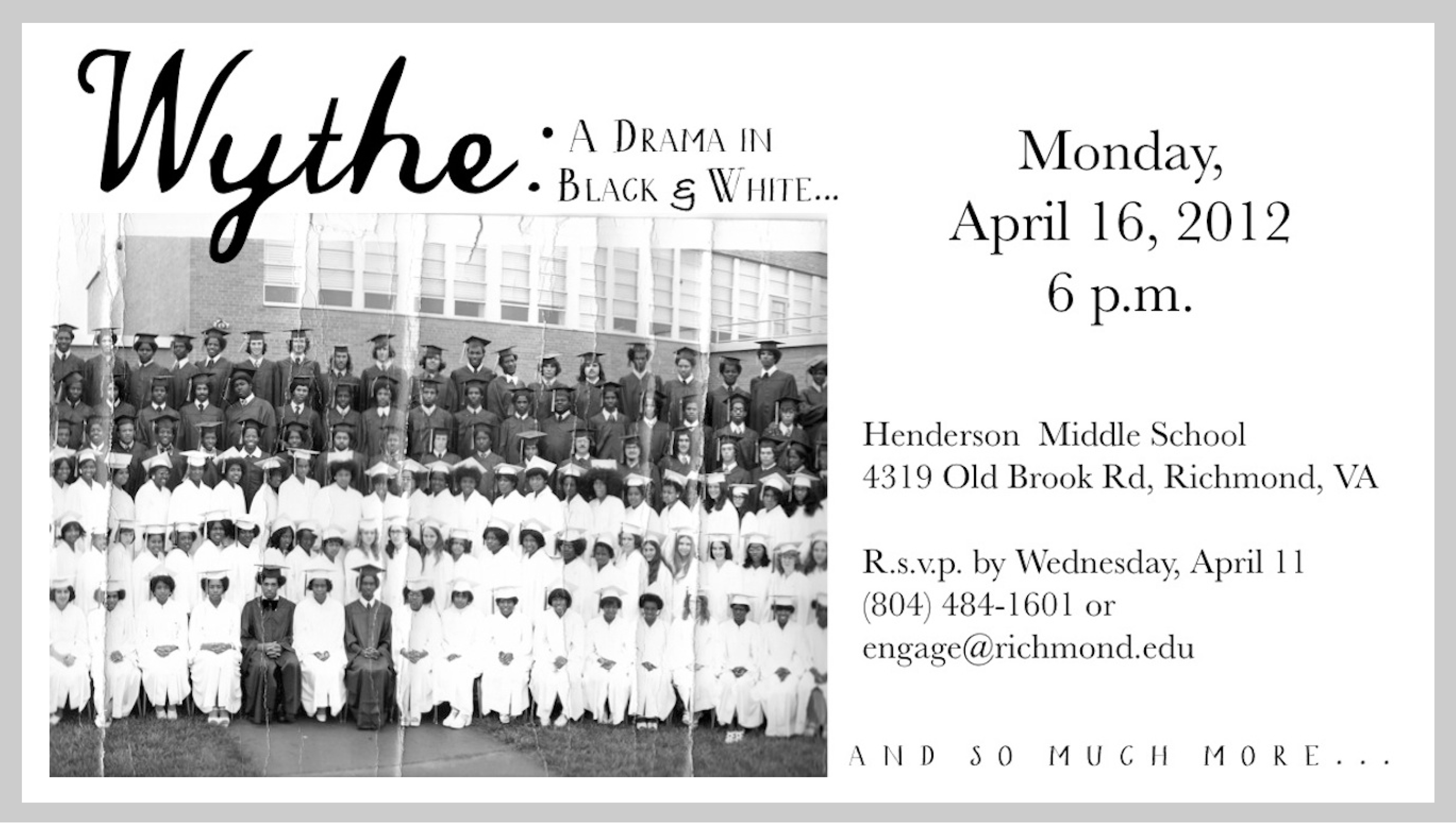

The Wythe archive—and the focus on Wythe—was an idea that came straight from the community. After the first year's performance, two of the postperformance panelists, both Wythe alums, had attracted us with their energy and passion. One of them, Mark Person, was deeply involved with an alumni group focused on helping current Wythe students. He persuaded us to center our second year's course on this one high school (fig. 1). We didn't realize at the time that one of the community's needs was to archive personal materials that had been scattered throughout Richmond.

When our digital archive team met as a group, we kept coming back to Salvador's inability to locate any of the high school's materials in a central archive. What if we used Wythe as the focus for some of our archival efforts—and if we got Wythe alums involved not only in oral history interviews but also in bringing in their memorabilia to share with our students and to have photographed for the digital archive?

Yet as Tee Turner of Hope in the Cities cautioned us when we first mentioned creating a digital archive, not everyone has access to this type of technology. Having a physical archive located in the heart of Richmond would make these materials available to this audience as well—just as our performances would reach Richmonders who may not be tempted to visit our website. Would the alums be interested in having us create a physical archive of their school's experience, which Wesley and Yuki generously offered to house at VCU?

Wesley and Yuki were the only professional archivists in our group, and they were emphatic that we needed to think carefully not only about what we wanted to collect in the Wythe archive but about how and why we would use it. VCU's James Branch Cabell Library would not serve as a repository but rather as a site for a living archive that could spark dialogue about Virginia's past. In its entirety, our new archive would be multimedia, multidisciplinary, and most of all, porous to the community—generated with different groups and institutions, from One Voice Chorus (which provided the music for our second year's performance) to Hope in the Cities to VCU Libraries to the Valentine Richmond History Center to Henderson Middle School. Contributors would range in age from ten years old to over sixty, and their memories would span decades.

The Archive Speaks

What it meant to make these private treasures public became very evident the day of our first group interview. We had invited alums to bring their memorabilia and had asked Wesley to bring donation forms and explain what the new Wythe collection would be all about and all the different ways they could lend or give their materials to VCU special collections.

One of our interviewees, Royal Robinson, brought pictures, a scrapbook, and a yearbook from his time at Wythe, a period in his life that he recalled as transformative. At the end of what had become at times an emotional discussion among the alums about busing, in which participants shared often conflicting memories about what had happened and what the meaning of the experience had been, Royal approached us, and told us that he was going to be praying on whether he should donate his materials. After looking through the yearbooks with our students, and telling them stories about some of the events and people depicted there, he decided that it was important to share these texts with the public.

What had been a purely private experience was now contextualized within the history our students were learning, thus changing the nature of how Royal and we understood the archive. It was the interplay between object and memory, contemporary viewers and contributors that enriched our understanding of the archive. And we were still exploring the link between archive, memory, and performance. Because our project had moved so quickly, developing in a year's time from a single course to a project with a five-year commitment, and a complex archival component attached to the theatrical productions, it was not until the night of our second year's performance at Henderson Middle School that we even knew what questions to ask about the living archive. The clearest example of this living archive centered on a scene in our play that had its origins in a group interview we conducted with 20 Wythe alums in our classroom. When asked to remember watershed moments during their high school years, many recalled the school's first-ever black history day (before it was a week or a month). Jeroyd Greene Jr., who later changed his name to Sa'ad al-Amin and became a polarizing figure in the Richmond City Council, was in the early seventies the lawyer for the Richmond chapter of the Nation of Islam. He referred to white teachers and security guards as "honkies" and "devils." The white alums in our class recalled how uncomfortable they had felt listening to this divisive speech, and the black alums talked about how they had sympathized with their white friends.

When in 1971 Greene injected his separatist rhetoric into this integrated space, in which there were strong bonds between white and black students, the effect on Wythe was profound: a huge percentage of white parents withdrew their children from the school the very next day, and friendships were broken. And in our class, which was evenly divided between white and black students, writing and performing the scene based on this incident brought the idea of black racism (which was very uncomfortable for the black students) to the surface. Not only did our students not know what the word "honky" meant, once they did know, they did not want to say it because it forced them to move beyond a celebratory vision of integration and revealed the contradictions of the civil rights movement.

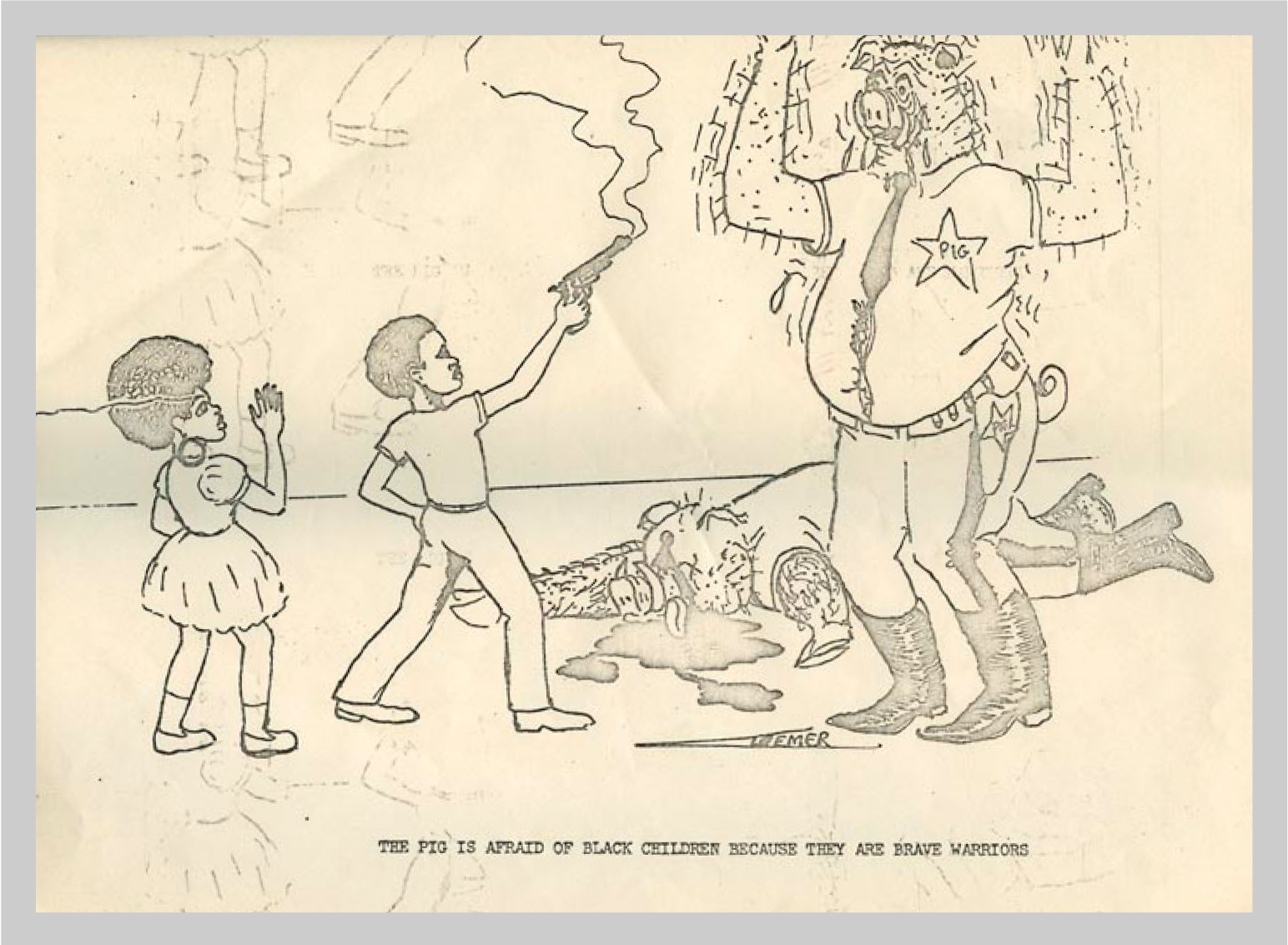

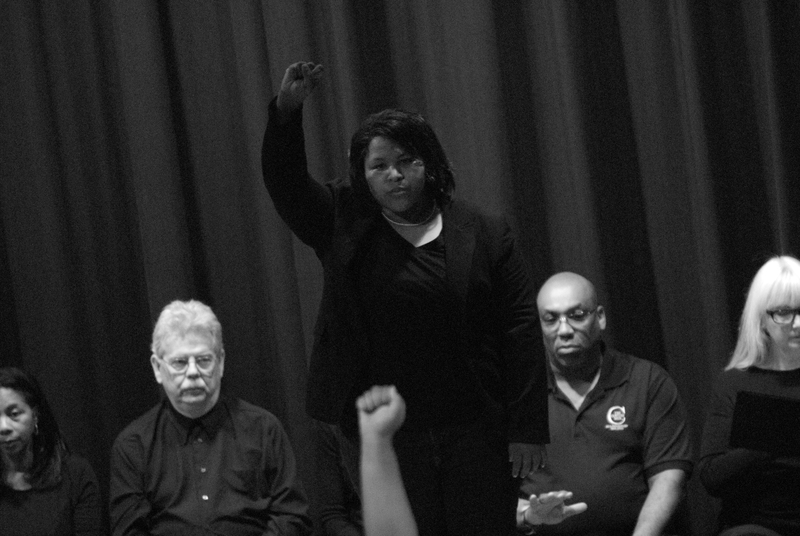

Getting the students to understand Sa'ad al-Amin's anger and the conflicted feeling among black and white students was a big hurdle for them to jump. The African American female student performing the role of Greene was a committed Christian activist for whom integration was an ideal. In the moment that she had to raise her fist in a black power salute, she felt a disconcerting disconnect between her own identity and that of the role she was asked to perform—even though she knew, on an intellectual level, that it was "just" a performance. Perhaps her next archival discovery helped her get over this hurdle: a coloring book ostensibly produced by the Black Panther Party that we found at the Valentine History Center. The illustrations featured black children shooting and stabbing white police officers with the faces of pigs (fig. 2). The coloring book was shocking, but what was more shocking to the students was the revelation that this coloring book had actually been produced by the FBI for the purposes of discrediting the Black Panther Party.

While Greene's anger had seemed to her to have no grounding, now our student understood some of where his rage against the "white devils" was coming from. The black power fist she raised in the performance came to stand for not only fighting for civil rights at that moment but also thinking about students in our current historical moment who are experiencing resegregation (fig. 3).

For the night of the play's performance, Mark Person, who had galvanized the Wythe alums to be part of our project, had assembled an elaborate poster display featuring newspaper articles about Wythe, autographs of team members, and other memorabilia. Groups of alums lingered to leaf through old yearbooks and reconnect with one another, gathered around the evocative objects representing their shared history. In some ways, Mark's was the kind of display that has gone out of fashion in the digital age—this looked almost like a science fair or history project one might have seen twenty years ago in a school corridor, replaced now by the PowerPoints that students more typically present. Yet it clearly moved those who saw it and thus encouraged them to unearth lost memories and recount the stories those memories sparked.

Later, we reflected on this display, and the engagement that participants and spectators had with it. We were struck by how much the poster display—a very old-fashioned kind of archive—had in common with the dramatic performance our students did that night. Both evoked powerful moments in history to bring people together, talking about their shared experiences, filling in gaps in memory, and finding points of disagreement as well as agreement about the issues that had mattered to them most.

All of the archival forms connected with our project—the Wythe collection that Wesley and Yuki created at VCU, the poster display, the digital stories our students had created about their interviewees, the "living newspaper" of our students' documentary performance—were also in dialogue with Nat Turner's bible, the family relic that Mark Person and his relatives had just donated to the Smithsonian's new African American Museum. Was it possible to draw a direct line from the bible of America's most famous slave insurrectionist to the digital story a student created about Mark Person's experience, which continues to this day, of consistently and unselfconsciously being the only white participant in an all-black softball league (http://thefightforknowledge.org/digital-stories)? It seems to us that all of these different archival forms are ways of helping us bridge this gap of nearly 300 years—and that witnessing and documenting the engagement that project participants had with one another and with these evocative objects of the past could help us to unpack Richmond's history in ways we never could have imagined.

How do we speak to an archive, and how might that archive, and its community, respond? By the end of the second year, we were beginning to understand our project as an archive, one to which we could keep adding new projects with new and existing partners. Rather than being a one-off, our five-year course would, we hoped, serve as a kind of living archive, a resource for creating projects ranging from theater performances to digital stories, from sound installations to photography and oral history exhibitions. Just as Mark Person had seen the first year's performance and had pushed us to move the project in a whole new direction—which in turn produced more ideas and projects—the ideas and artifacts that have surfaced during our project have continued to inspire the community around the course.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to our many partners on this project, including The Bonner Center for Civic Engagement at the University of Richmond, especially Amy Howard, Sylvia Gale, John Moeser, Terry Dolson, and Cassie Price; Kim Dean at UR Downtown; the Department of Theater and Dance, especially Debbie Mullin; the Program of American Studies; Hope in the Cities, especially Tee Turner and Cricket White; One Voice, especially Adele Johnson and Glen McCune; Henderson Middle School, especially Rosemarie Wiegandt; Katherine Schmidt for guiding students from Henderson Middle School with their digital stories; Salvador Barajas and Connor Dolson for all of their great work on the digital archive; VCU Cabell Library's Special Collections, especially Ray Bonis, Wesley Chenault, and Yuki Hibben; Meghan Glass Hughes at the Valentine Richmond History Center.

We are grateful for the willingness of many Wythe alums to share their stories, especially Mark Person. Thanks to all of our interviewees: Keith T. Andes, Sandra M. Antoine, Philip H. Brunson III, Fredrick D. German, Janice M. Hassell, Ray P. Kyle, James W. La Prade, Robin Denise Mines, Valerie Perkins, Mark Person, Thomas David Riddell, Royal L. Robinson, Elizabeth B. Salim, Randolph "Randy" Shelton, Claire Spicer, Laura S. Martin Summers, Gary W. Thompson, Anneliese Warriner (Ware), June (Dobb)Wilbert, Maurice Williams, Silas "Elwood" York.

And finally to the students, including Max Baird, Christina Brodt, Camden Cantwell, Kathryn Cohen, Renee Horen, Cheleah Jackson, Jessica Kelley, Amanda Lineberry, Jenna McAuliffe, Kelsey Mickelson, Charlene Morris, Amani Morrison, Michael Rogers, Katherine Schmidt, Danielle Stokes, and Cheyenne Varner.

Works Cited

Browder, Laura, and Patricia Herrera. 2012. "Civil Rights and Education in Richmond Virginia: A Documentary Theater Project." Transformations: The Journal of Inclusive Scholarship and Pedagogy 23 (1): 15–36.

Dawson, Gary Fisher. 1999. Documentary Theater in the United States: An Historical Survey and Analysis of Its Content, Form, and Stagecraft. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1999.

Federal Theatre Project. n.d. "Writing the Living Newspaper." Federal Theatre Collection. Library of Congress.

Martin, Carol, ed. 2010. Dramaturgy of the Real on the World Stage. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Pratt, Robert A. 1993. The Color of Their Skin: Education and Race in Richmond Virginia, 1954–89. Richmond: University Press of Virginia.