The Museum as Part of an Engaged Campus

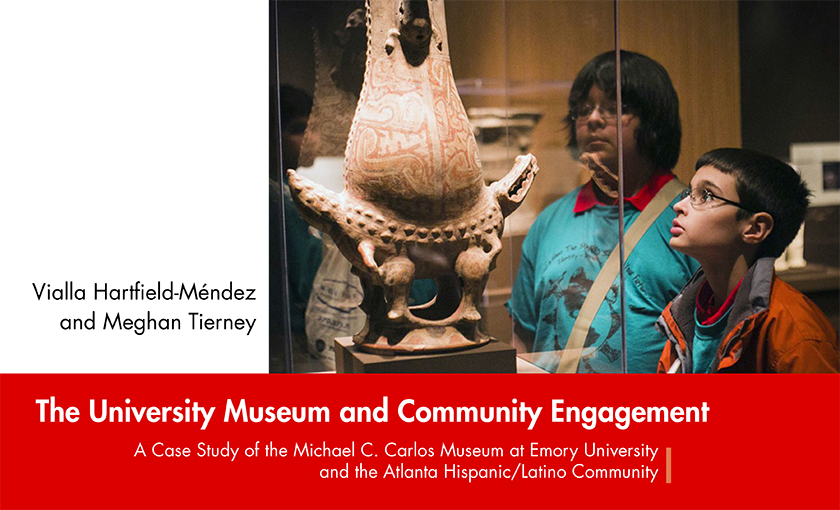

In a recent publication, "Campus Art Museums in the 21st Century: A Conversation," the Cultural Policy Center (CPC) at the University of Chicago examines the role of the campus museum in a rapidly changing higher education environment. For the museum administrators involved in this conversation, campus museums are uniquely situated in environments that both allow for freedom of innovation and require attention to many constituents. All have in common the need for "implementing effective strategies to engage faculty members, reaching out to students, and advancing multiple university-wide priorities" (CPC 2013, 6). In the CPC's framing of the campus museum, community engagement is viewed primarily as service to local community constituents, not as equitable community engagement and partnership. However, if the university or college in which a campus museum is housed aspires to be an "engaged campus," how can a campus museum such as the Michael C. Carlos Museum (MCCM) on Emory University's campus fully participate in that vision? To productively pursue this question, we take as a case study the MCCM's engagement with the Hispanic/Latino community.(1) We examine how the MCCM currently serves as a nexus for community engagement, interrogate the role of mediators within MCCM-campus collaborations related to engagement with the Latino community, and consider future actions that would move the museum toward even more inclusive partnerships.

Emory University aspires to be and in many important ways is an "engaged campus," as envisioned by Beere and others in their recent volume with that very title (Beere, Votruba, and Wells 2011). In fact, Emory's vision statement could be read as its "engaged campus" statement. (2) Following the Carnegie Foundation's definition of community engagement, Emory has collaborations and partnerships with its "larger communities (local, regional/state, national, global)" that are meant to be mutually beneficial and reciprocal. Importantly, in Emory's vision, as articulated by the Center for Community Partnerships (CFCP), engaged scholarship, learning, and service are linked and inform one another. (3) The MCCM has been an important locus on campus for these collaborations and partnerships. The museum's Education Department creates and administers numerous programs that attract visitors from the Atlanta area and well beyond. As a result of these and other efforts, the museum enjoys more than 100,000 visitors per year and through school programming receives around 30,000 schoolchildren annually. As we will discuss, the museum has also played an integral role in community-engaged learning courses that include its collections as part of interaction with community members. Yet in some ways, the museum has only begun to embody the vision of the "engaged campus."

We may think of the engaged campus as a woven whole, with activities, programs, offices, and partnerships creating a full tapestry that makes sense to the various parts of the campus as well as to community members beyond. Clearly, not every aspect of engagement with community or engaged learning is in lockstep with every other aspect; rather, they should be coherent, intentional, and consonant with the educational mission of the institution. In the aspirational engaged campus, campus constituents are aware of the institution's positioning and intersectionality in relation to the surrounding community and beyond. Thus, community-engaged learning, scholarship, and service are part of many conversations on campus rather than considered and developed in discrete pockets. All members of the campus—students, faculty, staff, and administrators—should be able to recognize and own their roles in community engagement. Similarly, community partners can be connected to many different parts of the campus in multifaceted and complementary relationships that develop and freely evolve over time.

What, then, is the role of a university museum within such a framework? For example, if community-engaged learning is an important pedagogical innovation on campus, what role might the museum play in this pedagogy and what are the implications for the museum's own positioning with regard to local communities? What is the role for mediation by other campus partners between the museum and local communities, such as mediation by offices for community partnerships between museum staff and community members or organizations? Is there room for direct collaboration among campus and community partnerships associated with the museum? How does the museum define community engagement and how might its definition be reexamined in light of the university's commitment to equitable and mutually beneficial partnerships? More important, does each division of the museum understand how equitable community partnerships can benefit and fit within the structure of their mission? To what degree does this resonate with the university's stated mission with regard to community engagement? Is the structure of the museum set up to meet these goals? Finally, what is the relationship between the museum's collections and the multiple communities who might engage with those collections?

To begin to answer these questions in the context of Emory, we begin with the MCCM's mission statement: The Michael C. Carlos Museum of Emory University collects, preserves, exhibits, and interprets art and artifacts from antiquity to the present in order to provide unique opportunities for education and enrichment in the community, and to promote interdisciplinary teaching and research at Emory University. The museum also announces itself as "a portal where the University and community meet, physically and intellectually" (Michael C. Carlos Museum 2013). While responsible to the vision of the university, the MCCM's mission requires that it also strive "to provide unique opportunities for education and enrichment in the community" (Michael C. Carlos Museum 2013). These statements offer a point of departure for community engagement beyond service to the community and outreach. A review of how this has played out with the Hispanic/Latino community in Atlanta, especially in relation to the Art of the Americas collection, offers a model for university/museum community engagement. It also reveals significant challenges, and both aspects are the focus of this essay.

The Civically Engaged Museum: A Nexus for Community Engagement

As Stephen Weil has pointed out, at its inception in the European context and recently in the United States, a century and a quarter ago, the museum's relationship with the public was created and maintained as "one of superiority" (Weil 2002, 195). Museums were understood internally and by the general public to be institutions dedicated to the study of objects meant to inspire wonder and amazement for their visitors. By the end of the twentieth century, however, the role of the museum began to shift away from a strict adherence to the mission to collect, to preserve, and to study toward "a transformed and redirected institution that can, through its public-service orientation, use its very special competencies in dealing with objects to improve the quality of individual human lives and to enhance the well-being of human communities" (emphasis added; Weil 2002, 29). This idea of extending a service toward a public audience, while clearly reorienting a museum's focus from an inward and rather insular gaze to a more outward and open one, nevertheless does not fully address the transformation that must occur for a campus museum to participate in and support the aspirations of an "engaged campus." Complicating the picture is that campus museums, positioned as part of a broader academic structure, are accountable to accrediting bodies such as the American Alliance of Museums, their university/college community, the objects they hold, the cultures and contexts from which those objects originate, and to other constituents, such as their supporting members. Service to all these constituencies is a seemingly impossible task as budgets are slashed and the humanities compete with STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) programs for support and attention.(4)

From a broader societal perspective, the role of the museum was reimagined further in a series of essays presented at the 1990 Museums and Communities Conference at the Smithsonian and published in a collection with the same title (Karp, Kreamer, and Lavine 1992). Especially useful to our discussion here is the distinction of the "dialogic museum," explored by John Kuo Wei Tchen. At a moment leading up to the quincentenary of Columbus's encounter with the Americas, Tchen challenges humanities institutions generally and museums in particular to consider how to include those groups that have not been traditionally implicated in "We the People" (Tchen 1992, 287). One approach is through the practice of dialogue, or the intentional creation of dialogic spaces facilitated by the museum, that depend on the full inclusion of community. This could be at the heart of any museum's approach to community engagement. Tchen observes:

a resonant and responsible way of engaging any community in the interpretation of its own history needs to balance local, intensely private uses of history with the larger-scale understanding of why and how life has become the way it is (Tchen 1992, 295).

In The Participatory Museum, Nina Simon (2010) argues for a renovation of the museum experience (and a revival of museums themselves) through "inviting people to actively engage as cultural participants, not passive consumers" (ii). She defines "participatory institutions" as "meeting grounds for dialogue around the content presented" (Simon 2010, iii). Thus, "instead of being 'about' something or 'for' someone, participatory institutions are created and managed 'with' visitors" (Simon 2010, iii). There are significant intersections between the idea of a dialogic, or participatory museum, and the organizing principle of the engaged campus and community-engaged learning, as both call for equitable and mutually beneficial partnerships. Both ideas are at play in the activities at the MCCM that are described here, though there is ample room for developing these aspects further. Many of the activities designed for the K–12 school programs are squarely aimed at making the museum "participatory" in the sense that Simon intends. And the community–campus partnerships in which the MCCM is an important player are intentionally structured as mutually beneficial and mutually informative. They are multifaceted and have short- and long-term consequences for the communities and for the university, including the museum. Yet, as we will see, these connections are more mediated than direct, and the possibilities for meaningful dialogic exchange are only beginning to be explored.

With this framework for the museum in mind, it is also helpful to consider campus museums within the rubric of civic engagement as defined by Campus Compact, which along with the Carnegie Foundation's definition of community engagement and others is a national leading organization in the field of community engagement, and of which Emory is an institutional member.. Using this lens, the museum might envision itself as an integral part of a university that: (1) "must provide students with the knowledge and commitment to be socially responsible citizens in a diverse democracy and increasingly interconnected world"; (2) has "important civic responsibilities to their communities, their nation, and the larger world"; (3) understands that "civic engagement involves true partnerships, often between the institution and the community in which it is residing, that serve mutual, yet independent interests, thereby honoring the integrity of all partners"; and (4) works toward partnerships that "can best serve society and the academy when connected directly to academic work, courses and activities" (Campus Compact 2013, 2). These are the goals for the engaged university; in its role as one piece of the university constellation, the museum can use these goals in planning internal programming, involving student projects and interests, and in seeking out collaborations with faculty and staff. The MCCM's mission and the university's vision are aligned in the pursuit of civic engagement and the university recognizes its museum as a point of leverage for community connecting. Notwithstanding, there are still significant gaps in the museum's (and the university's) ability to fully engage with parts of the Atlanta community that have been traditionally marginalized or that are recently emerging, such as the Latino population.

The linkage between the research mission of the university and the public good is clearly stated in the Summary Report from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation's College and University Art Museum Program (CUAM), which included Emory's MCCM. The report cites an Emory administrator: "One of the distinctive qualities of a research university is dealing with material culture. We need to persuade people why universities are worth investing in. They are not a 'private good;' the art collection is a broader public good. It is a way the university can translate its mission to individuals beyond its own alumni" (Andrew W. Mellon Foundation 2013, 21). At the same time, the focus of the Mellon Foundation's CUAM program was on curriculum, and for this reason, participant campus museums were encouraged to limit their scope to address their "primary" constituents, interpreted as those on the campus. This approach is inherently problematic, since it assumes that the campus and its curriculum are separate from the "public good." It is worth noting, however, that the MCCM was responding to these reduced parameters and that the CUAM program thus encouraged an inward-looking stance, focused on the campus, and did not encourage the museum to move beyond the notion of "service" to the public toward full engagement and dialogue with community members. Thus, while the museum does have a significant number of visitors, an impressive array of educational programs, and reaches out to thousands of schoolchildren per year, less attention has been paid to understanding the role of community in the museum. This is especially true for the more marginalized and traditionally less active segments of the community, especially with the Hispanic/Latino population in Atlanta.

The 15-year CUAM study of campus museums assessed outcomes on many levels. Regarding internal changes, the survey was conducted at a time when many museums were "adrift or at a turning point." In Emory's case, the "museum had just received a major infusion of collections, space, and funding, but had based its identity on international projects with little benefit to the campus" (Andrew W. Mellon Foundation 2013, 12). If there was at that time "little benefit to the campus," the connection to the larger community was even more tenuous. In the span of about a decade, an important new collection of early indigenous objects from Mesoamerica, Central and South America was integrated into the MCCM, the Latin American/Hispanic/Latino population in Atlanta grew exponentially, and the university energetically committed to community-engaged learning, scholarship, and service. The convergence of these three elements created the opportunity for the MCCM to connect with the Hispanic/Latino community through other campus entities, in mediated partnerships. In other words, the connection with this community would not have happened, or at least would not have happened in the period in which it did, without other campus initiatives and activities. Nevertheless, the foundation provided by the school programs and related events created by the MCCM's Education Department paved the way for engagement with this community. In the process, groundwork has been laid pointing toward the possibility of more reciprocal engagement. The MCCM has begun to move beyond the parameters of the CUAM review and to embrace an identity as an integral unit of an "engaged campus." As a result, Emory students can be better served in their learning process as they encounter the complexities of contemporary Atlanta. With an expanded notion of community engagement, community members can access a space of learning and culture that resonates with and considers their own experiences.

The MCCM's associate director affirms that the museum has for more than a decade made the case that, rather than having a "dual function" (one prong focused on service to the university community through research and teaching, the other on "outreach" to the local community), there is a "unified function"; these are not unrelated but are rather intimately related if for no other reason than the fact that members of the university community are also members of the local community.(5) For this reason, administrators have made significant efforts to maintain the educational programming division and further develop "outreach" to local, regional, and state K–12 schools. Use of the term outreach remains problematic, and small changes in language might serve as a starting point for transformation toward an equitable partnership or fully engaged model. Still another critical question is how to measure and fully understand the effects and results of actualizing this "unified function."

Connecting the Museum to the Latino Community: Understanding the Role of Mediators

The MCCM operates as an entity of Emory University; thus, the museum's relationship with Atlanta generally must be understood with the context of the university's relationship with the metropolitan area. Emory has a longstanding history with the founding and leading families of the Coca-Cola Company, with major gifts from their associated foundations marking many of the university's significant stages of growth. Among these is the Goizueta Foundation (created by Roberto Goizueta, Cuban immigrant and former CEO of the Coca-Cola Company). Through this and other similar relationships, by 2000 Emory had established strong ties with representatives of the earlier migration from Cuba. It had much less contact with the newest members of the Hispanic community, the recent immigrants mostly from Mexico and Central America who had become important players in the construction and service industries after the 1996 Olympic Games. Even in the MCCM, the acquisition of a major collection of ancient Central and South American had very little to do with the Hispanic community, since the objects were in a collection put together over many years by a native Atlantan in his travels. At the same time, in several Emory programs in area schools, students and faculty were increasingly encountering children who spoke Spanish (and numerous other languages), but even in the department of Spanish and Portuguese, there was limited contact with local representatives of the Hispanic and Lusophone cultures. There was, however, at the university, college, and departmental levels, a welling up of support for better understanding this part of Atlanta's contemporary reality and for establishing relationships with newer immigrants.

Just prior, in 1988, the museum acquired a collection of over thirteen hundred significant works of art from the ancient Americas, especially Costa Rica, from William C. and Carol W. Thibadeau (Stone-Miller 2002, xi). This gift coincided with plans to expand the museum at the center of the Emory campus. With this new collection installed into expanded galleries, the museum's Education Department began reaching out in significant ways to area schools and communities, though with very little connection with the Latino community. It bears noting that the Art of the Americas long-term exhibition occupies a prominent gallery space. In this regard, the MCCM stands in sharp contrast to typical placements of objects from cultures outside the dominant Western sphere in secondary and tertiary spaces. As a visitor passes through the main entrance, he or she is greeted with a spatially and visually orchestrated equal choice to begin a tour of the museum through the Art of the Americas or through the Greek and Roman collection. The acquisition also precipitated the hiring of Dr. Rebecca Stone as a Mellon postdoctoral fellow. Ultimately, Stone's role evolved into a dual appointment as professor in the Art History Department and the museum's curator of the ancient Americas. It was this scenario that provided a point of departure for collaboration among the MCCM, the Department of Spanish and Portuguese, the Center for Community Partnerships, and several other university units to create programming aimed at local schools with large Latino populations while also engaging Emory students.

Recently the museum has accepted a large donation of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Guatemalan textiles, including men's and women's traje (traditional dress) and ceremonial paraphernalia such as altar cloths and clothing for small santos (saint) figures. Since the 1993 installation of the Art of the Ancient Americas galleries, several individuals, including an Emory student, have donated molas (stitched dress panels) to the museum as well. Two Guatemalan huipiles (tunics) and two Panamanian molas are now installed in the current installation of the Art of the Americas galleries (opened in February 2013). The change in the gallery name reflects both the inclusion of these modern artworks and the addition of a gallery dedicated to ceramics made by North American Indian artists. With these additions, the exhibition now includes objects relevant to vibrant present-day cultures and to the individuals for whom that cultural connection resonates most personally. Moreover, the notion of what constitutes art in general and art from the Americas specifically is expanded across time and space. All of these points open up unexplored possibilities for engagement with not only members of the Latino community but also all the visitors to the museum.

With support from the newly created Office of University-Community Partnerships (recently renamed the Center for Community Partnerships), in 2002 the Department of Spanish and Portuguese offered its first service-learning course in Spanish (Spanish 317, "Writing, Context, and Community"), creating strong partnerships with nonprofit organizations and nearby schools with high percentages of Hispanic/Latino students. These partnerships were strengthened by a full integration of the students' engagement with the organizations into the fabric of the course and by writing projects designed to benefit those organizations and the communities they serve. By 2003, the department was looking to expand the service-learning opportunities in the curriculum and saw an obvious partner in the MCCM. Visits to the museum were designed to respond to the state-mandated school curriculum, which for the fourth grade includes the history of the Americas, to offer significant experiences for the schoolchildren. The visits included tours of the ancient Americas galleries, lunch sessions that offered bilingual reading time, and hands-on workshops, such as constructing a quipu, the Inka recording and storytelling devices made from a complex series of colored and knotted strings. Quipu making (in this case recording the number and gender of family members that live in your house) by both schoolchildren and Emory students alike, provides an efficacious means to elicit connections and active learning as they share and encode into their quipu a piece of their personal narrative. An e-mail from a fourth-grade educator whose class participated in a recent trip to the MCCM described how the day after the museum visit the "students wore their knotted necklaces and were 'reading' each others[']."(6) While a potential connection exists between the ancient American art and the cultural heritage of the schoolchildren, the museum visits were viewed as a first step in learning to be in a museum and on a college campus, as well as understanding objects connected to their cultural heritage as subjects of study, interest, and import.

Emory undergraduate students facilitated quipu making and bilingual readings, and assisted museum docents in the galleries. A requirement for student participation was attendance at an orientation that included information about the new Latino immigration patterns to Atlanta and Georgia, guidance about how to interact with children of different ages, information about the MCCM's ancient American collection, and training for specific activities. This was the beginning of a series of highly productive interactions between the museum and Atlanta's Latino community, in collaboration with (and mediated through) the Department of Spanish and Portuguese and other campus entities, especially the CFCP. Other departments and programs participated, incorporating these experiences into courses in linguistics and Latin American and Caribbean studies as community-engaged learning components.(7) These school trips developed within the context of the museum's educational programming for K–12 students generally but immediately took on a different character.

Concurrently, partnerships with organizations beyond the schools emerged. Thus, the university context within which the museum operates was becoming more intimately linked with the Latino community and opened further opportunities for the museum's engagement. Some of these opportunities are:

•The undergraduate admissions office stepped up recruitment efforts for Latinos, implementing a Latino visit day, "Éxito Emory," during which the MCCM's reception hall was used as a gathering space, and the galleries included in a tour for prospective students and their parents.

•The Department of Spanish and Portuguese, with support from various campus entities, partnered with the Mexican Consulate and DeKalb County Schools to create a monthlong Mexican Summer Cultural Immersion Program for elementary school children of Hispanic heritage, facilitated by an Emory faculty member, a graduate student, four undergraduate interns, and two elementary school teachers from Mexico. The museum's Education Department provided access for the children to the ancient Americas collection and related hands-on workshops.

•The Mexican American Legal Defense and Education Fund (MALDEF) was a partner in bringing Latino parents to campus, with a trip to the museum as a featured component.

•The Hispanic Health Coalition of Georgia partnered with the Center for Community Partnerships and the Rollins School of Public Health to produce a report on Latino health and to host a related summit at Emory.

•Most prominent, Emory's Office of Community and Diversity has partnered with the Latin American Association (LAA ) to host the LAA's annual Latino Youth Leadership Conference for the past two years. In fall 2012, about 1,400 Latino students from grades 6 to 12 from across Georgia, along with some 400 parent chaperones, teachers, and other school officials and college student volunteers, participated in the daylong conference, with multiple age-appropriate breakout sessions. The conference coincided with the temporary exhibition, For I Am the Black Jaguar: Shamanic Visionary Experience in Ancient American Art; and the museum's education staff worked with the organizers to host sessions for the teachers as well as gallery visits and workshops for approximately 300 sixth and seventh graders.

In each of the cases in which the museum has been involved with these activities, they have been mediated relationships; another unit of the university has been the lead entity in engaging the Latino community. As we have seen, this can be very productive but what might be possible if the partnerships were more direct? Would there be more opportunities for a real dialogue between members of the Hispanic/Latino community and the museum about its collections? Might there be opportunities for creating small "loan" exhibitions within community settings, for example? Would there be a more compelling and salient need for translation of museum materials into Spanish (or perhaps indigenous languages)? These are all questions that can now be posed because beginning steps have been taken. The challenge will be to see clearly what is next, while continuing the productive campus partnerships already in place.

What are some of the results for the members of the Hispanic/Latino community who have visited the museum? Perhaps the most significant and immediate result for Hispanic/Latino schoolchildren (a large majority of whom are Mexican or Central American) is that they find themselves acting as "cultural participants," encouraged to interact with objects that are part of their cultural heritage and that carry contemporary positive valence. For example, the 500- to 1,500-year-old ritual metates (grinding stones) in the museum bear a striking resemblance to contemporary versions and molcajetes (mortars and pestles) used in Mexico and Central America. A majority of the children in these schools or their parents are themselves migrants. Their countries of origin still very much culturally inflect their families' social habits, especially with regard to food. There are moments of instant recognition with the museum metates followed by a sense of possible integration into the museum and the university. A description from a paraprofessional in a local middle school illustrates the importance of this experience:

I just wanted to say how wonderful the day of activities was and to share some of the students' reactions during our discussion. I don't think some of the students realized how much they connected to and identified with their experience at the museum until we begin to discuss what they had learned. Everyone shared their favorite part of the trip and were fascinated by los metates and los chamanes. We even had several of the students who are usually the most challenging to engage running to the board to draw the different models of metates and explaining the function of each. They absolutely identified with what they saw! . . . I also had a lot of students ask how one can apply and be accepted to Emory.(8)

The result is an inversion of conventional teacher/learner roles, a concept in line with the "dialogic museum," in which Hispanic/Latino K–12 students become informers to Emory students, their teachers, museum docents, and others about their cultures because of their interaction with each other around a particular object in the collection. Generally, K–12 teachers set the expectations for a visit to a museum with roles divided between teachers (those imparting knowledge) and learners (those gaining knowledge). Yet, at certain moments, the children share their knowledge of how objects like these are used and thus become the voice of authority. For example, during the first several visits to the museum, the faculty and staff realized that many of the children recognized the grinding stones and indicated as much both verbally and with gestures. Some said "molcajete" (referring to the mortar and pestle used in many of their homes), and others made grinding motions with their hands. Engagement with the metates on view became the space for the children to take on the voice of authority on the objects, in an unexpected reversal of roles with the docents and Emory students. When this was recognized, one of the faculty members went to the largely Hispanic neighborhoods where these children live and purchased a molcajete, which is now used as a teaching tool in the metates exhibit area so that the schoolchildren can have the hands-on experience of demonstrating how it is used. Those early experiences also illuminated for the museum staff members and for the curator of the exhibit the contemporary cultural resonance of these objects for at least certain members of the Hispanic immigrant community in Atlanta.

Just as important for our discussion, however, is the effect of this engagement with the Latino community on the museum itself. There are several concrete ways in which the MCCM has responded to the presence of Spanish-speaking Atlantans, and therefore has a different narrative of its recent history than would have been otherwise possible.

•The MCCM has an active volunteer docent program that was initially one of the key components of the school visits with Hispanic/Latino students. The service-learning program with Emory students and these particular K–12 students has become a favorite among the docents but has required that they reconfigure their tours to include Emory student assistants and to interact with Spanish speakers and "heritage" learners. One docent learned Spanish over a period of several years to better engage these learners. This same woman, who facilitates the Inka quipu workshop, explains how she has gained, through interactions with the schoolchildren, "a whole new perspective in ways of thinking, seeing, and understanding." As a longtime Atlanta resident, she came to see the "mosaic of different peoples and cultures" in the Atlanta metro area, of which she was previously unaware: she was amazed to discover "that right here by Emory, just a few miles away, we have our own little Mexico."(9)

•The guided tours in the museum as well as workshop activities have been reconceptualized as a result of these visits. An example, as noted above, is the museum staff acquiring a volcanic stone molcajete because of Latino students' interaction with the ancient metates.

•The MCCM's educational programs department has long facilitated summer camps with different art themes. As a result of the partnerships with the schools with high Hispanic populations, specific camps have been run for certain schools, and scholarships have been provided for children to participate in other camps, including funds provided by docents who had been impressed with the children's responses to the ancient Americas galleries.

•The Education Department staff at the MCCM has also long been aware of transportation as an access barrier, since Emory is not easily accessible through mass transit. With the economic downturn and cuts to arts programs in the K–12 public schools, bus transportation from schools was often one of the first budget items to be eliminated. For two years, the MCCM was awarded grants from the Center for Community Partnerships to provide transportation for K–12 generally, and the CFCP continues to provide funding for two schools with large Hispanic populations as a support for the associated community-engaged learning courses. These grants make it possible for schools to participate in MCCM programming, allowed the museum to make the case to several donors that funds for transportation, however mundane that support might appear to be, is critical to the museum's goals.

•One result of collaboration with other areas of campus is that the museum has the opportunity to connect with events organized by these other entities. In 2008, the Schatten Gallery hosted an exhibition of Latin American posters from the University of New Mexico. Co-sponsors included the Latin American and Caribbean Studies Program, the Department of Spanish and Portuguese, and the Theory Practice Learning Program in Emory College. The Latin American posters exhibition and related workshops were included in the annual field trips to the MCCM from area schools with Hispanic/Latino populations. The staff of the MCCM helped to plan the integration of the exhibition into the usual activities in the MCCM, with the result that the K–12 school visitors and the Emory student assistants experienced the MCCM as fully integrated into the life of the university as the schoolchildren moved from tours in the museum to workshops in the Schatten Gallery and back to the museum. On another occasion, school tours to the MCCM coincided with a conference of international cartoonists at Emory that included a panel of cartoonists who addressed the issue of "Cartooning and Freedom of Expression in Latin America." Two cartoonists from Latin America led a workshop on their art form for the schoolchildren, assisted by Emory students, in the reception hall of the museum.

•Museum spaces have been opened to the Latino community beyond the school visits. The MCCM reception hall facilitates this integration of the campus with the community and is frequently used for concerts, public lectures, and other collaborations already mentioned. The most recent example of opening of the museum to the Hispanic/Latino community is the participation in the Latino Youth Leadership Conference.

•An important aspect of engagement with Hispanics in Atlanta and in Georgia is the necessity of communication in Spanish, especially since this population includes many recent immigrants whose first language is still dominant. Inclusion of Emory students who speak Spanish or who are improving their Spanish skills is one of the ways in which the museum space can be transformed into a welcoming space for Spanish speakers. The MCCM translated the "family guide" for the ancient Americas collection into Spanish, working with an advanced student and a professor in the Department of Spanish and Portuguese. As the collection has been recently reconfigured and curated, there is currently a need for new materials, resulting in a need for more translated information.

Expanding the Museum's Narrative: Further Questions and Next Steps

Despite the success of a long-standing relationship with the Hispanic/Latino community in Atlanta, the MCCM has discovered that "change in the museum's narrative or content as a result of engagement in temporary exhibitions or activities is often short-lived" (Keith 2012, 52). While short-term topical exhibitions often attract members of communities whose interests and/or heritage relate to exhibition content or subject matter, according to the MCCM's director of communications and marketing, the museum has few ways to measure the learning outcomes of these visits or even whether visitorship is repeated. The effects of the permanent exhibition of the Art of the Americas might be better understood through the success of the programs mentioned above. This in turn points to the need to ask different questions and to acknowledge and build on the programs that create transformational programming and moments not typically considered within the rubric of success. The participants in the "Campus Art Museums in the 21st Century" conversation perceive a unique capacity of university museums that derives from their connection to the educational mission:

Because an important function of campus museums is to encourage innovative forms of pedagogy across disciplines, […] risk-taking is valued and "failure" is perceived as both more informative and less threatening than it might be in other kinds of museums. Further to that point, the core mandate of campus museums—making a curricular impact—was seen by participants as allowing them to use different (or at least additional) metrics of success than the overall number of attendees, which is how most other kinds of museums have traditionally gauged success (CPC 2013, 5).

Within many campus museums and certainly in the case of the MCCM, "museum personnel have learned that by specifically collaborating with students and faculty in departments not usually associated with visual arts, they are able to extend the reach of the museum" (Glesne 2013, 164). The Mellon CUAM program found that in fact "at Emory, faculty were encouraged to seek "out of the classroom" teaching activities; they found the museum a ready participant—sixty faculty used it in 2004–05" (Andrew W. Mellon Foundation 2013, 9). The MCCM sees its mission as a unified one that builds connections to the campus and to the Atlanta community through its Education Department. As Emory pursues an engaged campus model, a vision that understands and engages with community broadly is fundamental. The MCCM, like many campus museums, must continue to prove itself an integral piece of the university mission or risk becoming marginalized within the university structure.

The museum has in the past and continues to serve the university in its aspiration to be an engaged campus by full participation and investment in that mission. To build on its successes, the museum might envision a reformulation of how it defines "service to the campus." Using as a framework the pedagogy of service learning or community-engaged learning, in partnership with academic departments, the museum can compellingly argue that it provides a locus of innovative pedagogy that serves the university students by facilitating connections with the community. The measures of success within this framework are quite different from the traditional measure of counting attendees. The museum might consider qualitative measures of success and create partnerships with academic programs on campus that could facilitate both qualitative and quantitative evaluations of specific educational programming. To measure success or impact in innovative ways may contribute to the creation of a "culture" shift within the museum, which in the case of the MCCM moves from one focused inward toward Emory's campus to one directed outward into the greater Atlanta community. In the pursuit of the engaged campus vision, the challenge becomes how to make these outcomes visible and valuable if they are not being measured and to find meaningful ways to measure and report them.

Campus museums such as the MCCM are faced with many challenges, not the least of which is how they define their relationship with the communities surrounding the university or college they were designed to primarily serve. Most campus museums have defined their relationship to surrounding communities as secondary, understanding their first allegiance and responsibility to campus constituents. Nevertheless, the participants in "Campus Art Museums in the 21st Century" conversation noted that the "multi-layered, multi-stakeholder environment is part of what makes campus-based museums unique among cultural institutions" (CPC 2013, 13). On the basis of the experiences with the MCCM and the Atlanta Hispanic/Latino community over the last decade, it is clear that forging and fostering on-campus partnerships centered on engagement with community allow for seemingly competing constituencies to converge. Thus, community engaged learning, especially in the context of a university or college that has made a commitment to the notion of the "engaged campus," offers campus museums an innovative context in which to reimagine their roles, both on campus and in our society. These same community-engaged learning opportunities require collaboration with other entities in the university, which can result in less direct partnerships with marginalized communities and therefore less opportunity for a dialogic relationship with them. This is the next challenge that campus museums such as the MCCM, other university units, and the community must face together.(10)

We are indebted to the following for their assistance and conversation: at the Michael C. Carlos Museum, Bonnie Speed, Director; Catherine Howett Smith, Associate Director; Elizabeth Hornor, Director of Education; Julie Green, Senior Manager of School Programs and the Docent Guild; and Priyanka Sinah, Director of Communications & Marketing; and at the Center for Community Partnerships, Maureen Sweatman, Director of Operations.

Work CitedAndrew W. Mellon Foundation. 2013. Summary Report: College and University Art Museum Program. Accessed February 20. http://mac.mellon.org/CUAM/cuam_report.pdf.

Beere, Carol A., James C. Votruba, and Gail W. Wells. 2011. Becoming an Engaged Campus: A Practical Guide for Institutionalizing Public Engagement. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Campus Compact. 2013. "Center for Liberal Education and Civic Engagement." Accessed on February 21. http://www.compact.org/wp-content/uploads/clece/CLECE-brochure.pdf

Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. 2013. "Carnegie Classifications." Accessed February 20. http://classifications.carnegiefoundation.org/descriptions/community_engagement.php.

Cultural Policy Center of the University of Chicago. 2013. "Campus Art Museums in the 21st Century: A Conversation." Accessed February 20. http://culturalpolicy.uchicago.edu/campusartmuseums/.

Emory University. 2013. "University Vision Statement." Accessed February 20. http://www.emory.edu/president/governance/vision_statement.html.

Glesne, Corrine. 2013. The Exemplary Museum: Art and Academia. Edinburgh: Museums Etc.

Hartfield-Méndez, Vialla. 2013. "Community-Based Learning, Internationalization of the Curriculum, and University Engagement with Latino Communities." Hispania 96 (2): 355–68.

Hodges, Rita Axelroth, and Steve Dubb. 2012. The Road Half Traveled: University Engagement at a Crossroads. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press.

Keith, Kimberly F. 2012. "Moving beyond the Mainstream: Insight into the Relationship between Community-Based Heritage Organizations and the Museum." In Museums, Equality, and Social Justice, edited by Richard Sandell and Eithne Nightingale, 45–58. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

Karp, Ivan, Christine Mullen Kreamer, and Steven Levine. 1992. Museums and Communities: The Politics of Public Culture. Washington DC: Smithsonian Books.

Michael C. Carlos Museum. 2013. "History & Mission." Accessed February 20. http://www.carlos.emory.edu/about/history-mission.

Simon, Nina. 2010. The Participatory Museum. Santa Cruz, CA: Museum 2.0.

Stone-Miller, Rebecca. 2002. Seeing with New Eyes: Highlights of the Michael C. Carlos Museum Collection of Art of the Ancient Americas. Atlanta, GA: Michael C. Carlos Museum, Emory University.

Tchen, John Kuo Wei. 1992. "Creating a Dialogic Museum: The Chinatown History Museum Experiment." In The Politics of Public Culture, edited by Ivan Karp, Christine Mullen Kreamer, and Steven D. Lavine, 285–326. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Weil, Stephen E. 2002. Making Museums Matter. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

1 The use of both terms is intentional. As a cultural construction that emerged in the United States, "Latino" is fully embraced by many people of Latin American, Hispanic, or Spanish-speaking heritage yet is also a term that sits uneasily for many immigrants, who, on entering the United States, discover a new, imposed identity as "Latino/a" that actually serves the dominant culture better than it does the multiple and multifaceted groups to which it attempts to refer. "Hispanic," while generally referring to those who come from a Spanish-speaking heritage and for some is more familiar, is also broad; in fact, many immigrants actually prefer to self-identify as from their home countries (Mexican, Colombian, etc.). The use of both terms gestures toward, though of course does not resolve or fully elucidate, these complexities.

2 "Emory: A destination university internationally recognized as an inquiry-driven, ethically engaged, and diverse community, whose members work collaboratively for positive transformation in the world through courageous leadership in teaching, research, scholarship, health care, and social action." Accessed April 16, 2013. http://www.emory.edu/president/governance/vision_statement.html.

3 Along these lines, and in addition to this inaugural year of the Imagining America Graduate Fellowship at Emory, the dean of the Laney Graduate School has now committed to funding the position for at least two more years in anticipation of Emory's role as host institution for the 2014 Imagining America National Conference.

4 In the specific Emory context, for example, recent announcements of cuts and program suspension included the elimination of the Visual Arts Department, a natural campus partner of the MCCM.

5 Catherine Howett Smith, personal communication with authors, February 6, 2013.

6 Ingrid S. Del Real, fourth-grade educator, Montclair Elementary School, DeKalb County Schools, e-mail message to Meghan Tierney, April 12, 2013.

7 For a fuller description of these curricular developments, please consult Hartfield-Méndez (2013).

8 Rachel Kotler, e-mail message to Vialla Hartfield-Méndez, March 9, 2005.

9 Vanessa Wardi, letter written to Vialla Hartfield-Méndez, April 9, 2013.

10 Elizabeth Hornor, MCCM Director of Education, personal communication to authors, February 6, 2013.