Beyond Mass Incarceration: New Horizons of Liberation and Freedom

Editor: Ofelia Ortiz Cuevas

The architect of the largest prison-building project in the history of the world, the US now holds over two million people in cages across the country with over five million people on parole or probation (Wagner and Sawyer 2018). In the 1970s, there were roughly 200,000 people in jails and prisons across the country (Bonczar 2003); this amounts to a 500% growth in fewer than 25 years, which happened through an unprecedented investment and reliance on state security systems in the form of policing, court systems, and prisons. There are now roughly over 7 million people dispossessed from family, work, educational opportunity, and community due to mass imprisonment at a cost of close to 80 billion dollars a year (Wagner and Rabuy 2017) to all of us. And nearly 60% of this population are Black and Brown men, women, and children and almost all working class or working poor (PEW n.d.). It is a significant population of rightless, stateless persons unseen and unheard by those of us on the outside, existing mainly in the imagination as a dangerous, predatory people and a threat to the social fabric of the US. This investment by the state and the public has negated the future and freedoms of entire neighborhoods and communities across the country, and calls into question the very ideals of democracy that the US champions. For 15 years my students and I have been asking these very questions: Why so many prisons? Why in the US? Why in California? And why is the population that fills prisons disproportionately Black, Brown, and poor? And what does this mean for all of us?

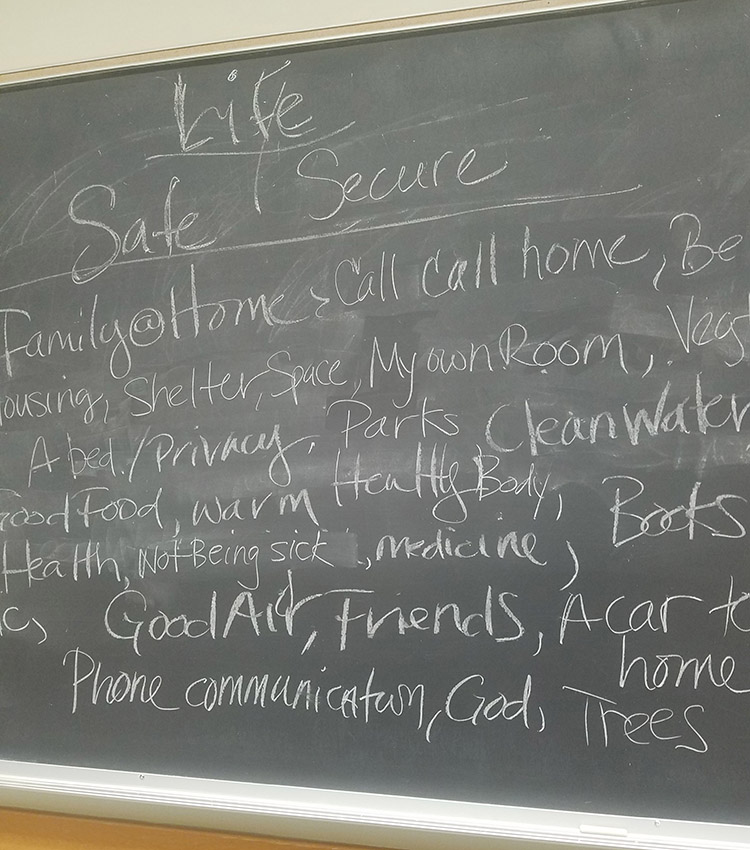

It was on my drive to teach my Race and Prisons course during my first year as a UC Davis professor that an answer came to me—or at least part of one. After many years teaching classes on prisons, policing, and race in the UC system, I finally had a steady gig that would allow me to expand and deepen my course on race and prisons and the contemporary crisis of mass incarceration and start looking for solutions. I was prompted by a lecture several years ago by Robert Rooks, VP at Alliance for Safety and Justice, on the current state of incarceration in the US when he began with a question, “What really makes you feel safe and secure in the world?” It was a revealing and liberating exercise that he ran with the audience and I decided to begin my first UC Davis class with that same question. I have done the same with each of my classes since. Students sit quietly sometimes thinking and then the answers come and I begin to make lists. And like that first lecture, over the next couple of years never once did police or prisons make the list. The top answers were knowing that their family and friends were “home and ok.” That they had a place with some privacy to go home to, school, knowing things, that they could pay their bills and buy the books, that they had clean water and air. That they had food to eat, that they would graduate, and that they had reliable transportation so they could get home. The lists looked something like this:

To teach the history of prison building and race from a historical, materialist perspective in some ways liberated the students from an entrenched understanding of crime and prisons as something natural and unchangeable—“there is no way for there to be no prisons,” students would say. And for those students that had been incarcerated or had immediate family in prison, their lives and futures began to mean something different. There was a spark of hope that I would see when they realized that prisons were built from the ground up, through decisions made by people—the people—just like them. Understanding that prisons were built in real time through real material and political relations, meaning a lot of capital and investment, changed the trajectory of the course to focus more on questions such as, “What else could we do with all that money?” and students’ imaginations took the questions and ran.

The work to undo this investment, emerging over the past 25 years into the public consciousness, has recently been considered by larger, more mainstream political and social structures, such as nonprofit campaigns, foundation monies, academic scholarship, and policy makers, with indignation and sudden alarm. Mass incarceration is suddenly no longer seen as a viable answer to secure the safety of the public by those who acknowledge that we as a nation have exceeded an acceptable amount of state-sanctioned racial violence. It is a “new” moral and ethical acknowledgment that has now, in fact, become a bipartisan movement—politically trendy even—in surprising, yet still dangerous forms. Recently, Vice President Mike Pence stated that criminal justice reform was necessary to ensure more public safety and to help the millions of formerly incarcerated “find a path to success so they can support their families and communities.” Working with Jared Kushner, as well as Van Jones and even Kim Kardashian, who gave council to the President, Pence led the way in passing the First Step Act, hailed as a landmark in criminal justice reform, which amended/repaired the excesses of mass imprisonment. As surprising as these unlikely alliances may appear, they are not so surprising when you realize that the massive prison-industrial complex was a solidly unified political project built by Democrats and Republicans, liberals and conservatives alike. The appeal of the acknowledgment resides in the idea that mass incarceration overreached, exceeding what is an appropriate number of people whose lives are destroyed by it. The move to find a more reasonable number of imprisoned people or to create reasonable conditions—kinder, gentler, environmentally-safe incarceration structures—will, unfortunately, not undo the devastation that has already been caused by the prison-building project. Such action avoids the material and racial entrenchment of imprisonment that resides in the foundation of the US.

To be sure, this acknowledgment is not only confounding but late in coming, as the massive growth in prisons in the last 35 years has changed the very structure of the country, a change that can be clearly seen in California, the state considered ground zero of US prison building. And yet from 1852 to 1983, California had only 12 state prisons. The earliest was San Quentin State Prison, now the largest death row facility in the US. For 130 years the state functioned with these 12 structures. But in 1983, the first of what would become 23 new prisons built through 2010 opened. In the 1990s, California was building almost a prison and a half a year (“California State Prisons Chronology” n.d.).

And during that stretch of time the state built one UC—the University of California, Merced. The logic that undergirded the California prison corridor, the stretch of the central valley where more than half of the new prisons were built in the 1990s, was that prisons would create jobs and revenue in the rural, “rust-belt” towns of the central valley (a model that was replicated around the country) (Pyle and Gilmore 2005). The verdict is out on the success of this plan, and yet UC Merced, as of 2018, has already infused 3 billion dollars into the state economy, 1.6 billion in the San Joaquin Valley in the form of salaries, goods, and construction awards (University Communications 2017). A small city has come alive and the entrenched prison “structure of feeling” is disrupted.1

As Ruth Wilson Gilmore explains, this state prison-building project was a geographical solution to a socioeconomic problem brought on by the crisis of surplus land and labor caused by neoliberal movements of globalization (2007). Prison building managed the excess of people (particularly Black and Brown) and land that had become surplus capital, and was fueled by the remnants of the late 1960s law-and-order agenda of the Nixon administration (that became the War Against Drugs) as well as anti-Black and anti-people-of-color public sentiment. The result was one of the largest state building projects in the history of the world, with devastating effects. The investment in control and containment of whole populations of people in tandem with a disinvestment in public good or social welfare projects and the increasing move to austerity agendas in neoliberal fashion further manifested difference along race and class lines.

The building of structures that control, contain, and cage human beings as a quick solution to a political and economic problem is not so much new as rearticulated and reanimated. This carceral logic is intrinsic to racial structural violence that has taken the lives of millions and has been historically an integral part of US nation building. It is revealing an exercise of racism and racial animus renewed under the continuation of practices of control, containment, and management. The examples are many: Native American reservations, Southern slave-holding plantations, Japanese internment camps, and the policing and repatriating of Mexican-origin peoples (most of whom were US citizens) in the 1930s, to name a few.

The present conditions that arise from this history have been theorized and recognized as points to better understand how the US became the largest incarcerator on the planet and why. The early work of the prison-building project that we now contend with has been explained by scholars who have been writing about this unprecedented prison growth for more than 25 years, and have provided a way to understand and explain this growth as a response to political and economic conditions and choices. Scholars such as Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Angela Davis, Christian Parenti, Steven Dozinger, and Mike Davis began connecting the turn of the century prison-building project to the volatile shifts of late capital and neoliberal globalization. What this scholarship did was provide new kinds of answers to the obvious questions of why there were so many prisons and why there were so many people of color in them. Their answers shifted away from prevailing ideas of crime and criminality as something behavioral or causal and anchored the problems of incarceration in the construction of a material history.

And growing out of this inquiry, the work of Critical Resistance became the central example of people’s recognition of how firmly entrenched was the belief that prisons had become a remedy of society’s ills. Formed in 1997, Critical Resistance brought together over 3,500 activists; academics; former and current prisoners; labor leaders; religious organizations; feminist, gay, lesbian, and transgender activists; youth; and families to challenge what became known as the prison-industrial complex at multiple levels. Critical Resistance made it possible to imagine the unimaginable—a world without prisons—and ask questions about race and state power, informed by the growing body of scholarship at the time. The organizing work of CR intersected and enabled more recent activist scholarship that supported the Critical Resistance abolitionist perspective. The work of Nicole Fleetwood, Dylan Rodríguez, Dean Spade, Rashad Shabazz, and our contributor Martha Escobar, among others, furthered the understanding of the phenomenon of prison building as a history of choices, decisions, and intent by the state that played out not as a response to crime and a need for public safety, but as a way of managing and ordering whole populations of people. This work took on how carceral logic intersected with race, education, gender, and capital in ways that revealed simple reform would not work to dismantle prisons with “the master’s tools” (Lorde 2007).

In this continued work, it became even clearer that the building of prisons and the caging of human beings only ensured the allotment of diminished life chances and the un-projected futures along lines of race, gender, and class difference. This was often the dismal conclusion even for my own students, as they now felt liberated by understanding prison building as something made of human intent. But, as the CR movement empowered us to understand: if it could be made, then it could be unmade. But how?

The light that went on that day now feels late in coming. For so long, I had been explaining to students the basic answer to the question of why so many prisons, why so many Black and Brown people, as something that was constructed and built through a series of political and economic decisions, a history made up of intention and interest; that I was not dealing with the future—their futures. I was providing a historical and material explanation of the present conditions that we all live (increased registration fees, student loan debt, diminishing value of a UC four-year degree, and family members in prisons across the state, meaning their own family money being used to cage their own brothers and sisters) but provided no real tangible solutions according to them. “It just feels hopeless.” “What can we even do?” they would say, or “What does abolition really look like anyways?” “It’s not real.” They wanted something real and they wanted some hope they could put their hands on and they wanted to look forward to the future.

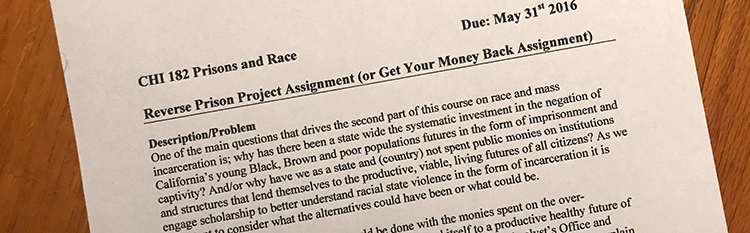

So, in my class I asked them to build us something different—to imagine a structure that would create more safety and security as they understood them for the people of California. The idea was if the people and governing bodies of California decided to invest in many prisons, but only one UC for 30 years, what would you build with the same money if you got to decide? The assignment looked something like this:

And what they imagined was amazing. Students turned prisons into large people-based structures that produced food, provided shelter, expanded knowledge and creativity. Pelican Bay turned into a multi-platform art facility with dance and theater programs, a cutting-edge visual arts department, even a component dedicated to art and healing. Folsom State prison became a massive community garden for the homeless in Sacramento County that utilized energy from the American River. One student project utilized the $13.1 billion yearly budget for maintaining San Quentin to build the San Quentin Marine Discovery Center that utilized 30 acres of unused land to conduct research on the impact of urban centers, nautical traffic, and human activity on wildlife and water quality. The center included a veterinary hospital and medical training for students as well as a childcare facility that was available to all employees (which they estimated at 1,000, between staff and students). There were summer camps to teach families how to interact and engage with nature and the holistic practice of preservation. The students stated that the San Quentin Marine Discovery Center “will strive to place our values before economic growth. We value the preservation of wild and sea life. We value the needs of our human staff. We value the preservation of land this center will be on. We hope this will be a safe place for all involved.”

And it is here that this issue begins—with the human lives affected directly and indirectly by mass incarceration and their resistance to it and their demands for something different. The contributors to this issue have taken on mass incarceration from lived and long experiences with it as scholars, practitioners, artists, and formerly incarcerated peoples heavily impacted by the system of incarceration. They take this issue on as I do—as people related to imprisonment in the everyday spaces they live in. This essay, as you will read in the others, began from the place that I live and work as a longtime scholar of race and imprisonment, as a Californian, and as someone whose life has been directly affected by the decision to build structures of unfutures and unfreedom versus places of viability.

On behalf of the entire editorial team, I hope you will find, through the voices of this issue’s contributors, the value of similar experiences, both individual and collective, for potential transformations of these structures. They build on the rich body of work from the last century that shifted public awareness and academic discourse in important ways, and provided critical frameworks and tools for engaging today’s challenges.

The pieces in this special issue include documentations of performances, discussions about them, and reflections on the power even of viewing them. They present the efforts of academic-community collaborations to share and discuss critical writing and innovative projects that seek to improve life transitions after incarceration. They describe to us new pedagogical approaches and pedagogies tied to groundbreaking research initiatives. And they detail the potentials and challenges of bringing institutional, geographical, and demographic information to a public audience in an effort to raise questions that are too often not asked.

We are honored to host this incredibly rich array of efforts to challenge the status quo of a system as deeply entrenched in our culture as this. We hope you will be as inspired as we were.

Notes

1 Raymond Williams’s concept of structure of feelings “refers to the different ways of thinking vying to emerge at any one time in history. It appears in the gap between the official discourse of policy and regulations, the popular response to official discourse and its appropriation in literary and other cultural texts” (Oxford Reference n.d.).