Abstract

This paper explores and examines the institutional barricades and borderless possibilities that bring people, policies, and programs together in service of social change. Toward this end, I interrogate scholar-activism from three distinct vantage points that inform my vision of cultural justice: the murder of Stephon Clark, the tensions surrounding authentic community-engaged work, and the vivid “call to arms” by the youth of Sacramento. These kinds of arms reach out, grab hold, and do not let go. It is here, inside the collective pulse of our existence and resistance, that the voices of artists, activists, and academics become harmonious chords in the choir of liberation.As an academic administrator, founder of a youth empowerment organization, and a scholar of racial justice, I traverse between drastically different community, university, and school environments. Within an afternoon, I will go from an administrative discussion on campus to a meeting with young people in the hood. Because of the polarities, I often get pulled into spaces where I feel myself becoming a cultural broker and code-switcher. While this can serve to build important institutional and interpersonal bridges, there also comes a time when our tongue and tone can no longer double Dutch. Our warmth becomes complicit, our liberalism part of the lie.

Today is not for the faint of heart; it is not business as usual.

I am sitting in my office grappling with this concept of community-engaged scholarship and how it manifests itself in real time, on the ground, in and around the University of California, Davis. A large part of my work and research contends with moving ecosystems of oppression towards ecosystems of equity. This paper tries to continue the conversation. Here, I am wrestling with the institutional barricades and borderless possibilities that bring people, policies, and programs together in service of social change. Toward this end, I will examine scholar-activism from three distinct vantage points that inform my vision of cultural justice.

Rise in Power

Along the long line of state sanctioned murders of Black and Brown men, women, and children at the hands of the police that continue to plague our society, it bereaves me to add a 22-year-old ancestor to this litany of lost lives. On March 18, 2018, Stephon Alonzo Clark was murdered by the police in his backyard in Meadowview. This neighborhood is a beautiful community that is culturally rich, yet remains a disenfranchised pocket of Sacramento, the capital city of California.

Stephon Clark was killed just 25 miles from the main UC Davis campus that is nestled within a quaint, quiet biking town. Although it is not too far away from Meadowview physically, the gaps between these two neighborhoods (95832 and 95616) are ideological, racial, and economic. Two-thirds of residents in Davis are white, while Sacramento is heralded as the tenth most diverse city in the US. Family income in Davis is about four times as much as that of the poorest adjacent neighborhoods in Sacramento. We may witness the same sunset, yet our horizons are viscerally different on measures of health, access, equality, and opportunity.

It took me 24 hours to find the strength to watch the video footage of Stephon Clark’s murder. Although police brutality is not new, the cameras have added a dimension of witness that further implicates all of us. As I watched the videos (those from the helicopter as well as from the officers on the scene), I could not stop thinking about the long history of state-sanctioned violence. A noose-less lynching: public, legal, brutal, and deadly.

Warning: The police video cam is graphic and traumatizing; however, it is important for us to serve as witnesses to the inhumanity. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VTlZqEsPY78/In the aftermath of Clark’s killing and with the release of the video footage, I felt a collision of conscience. I expected this local atrocity to precipitate all conversations on campus, but for most of my colleagues, they hadn’t even heard what had happened. There was this gap, again, vividly demarcating different realities. I felt trapped inside the ivory tower and grappled with being on the wrong side; I felt useless glued to the computer.

But then, in a serendipitous moment, I opened one of my student’s dissertation proposal. Inside the storm of Stephon Clark’s murder, I began reading the work of Jennifer DeBarros, a doctoral candidate at the University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth. Her research analyzes the culture of memory, police shootings, and public pedagogy. The preeminent carceral state of existence permeated her examination as she exposed the visceral, intergenerational traumas of police brutality. She also shared, at length, about her former student who was murdered by the police in New Bedford in 2012. In her dissertation proposal, DeBarros writes, “Although some cases like this gain publicity in mass media or become the catalyst for mass social justice movements, there is very little research about the ways that individuals who are closely impacted by these traumatic events make meaning of the experience and how such insights may be transformative in designing cultures of care that nurture and engage youth and families, ultimately improving the conditions of the whole community. . . . In this way, Malcolm’s deprivation of life, will serve as a meaningful and valuable contribution to both scholarly and community endeavors through the insights, memories, and stories of those most often silenced, misrepresented, and misunderstood.” As I read these words, my eyes became wet with tears. This is Sacramento—right now.

Scholarship is vital to our lives. As a case in point, I did not just read this dissertation proposal out of a professional responsibility as a committee member; I devoured her emerging scholarship because of its relevancy. Her research served as an intellectual sanctuary of answers to the real-life injustice of this very moment. I realized that even though DeBarros and I are on different sides of the country, our youth work has led us to the same funerals.

The killing of Clark substantiated that low-income African Americans are not safe in Sacramento—not even in their own backyard. Inequity is not just implicit bias that leads a fearful officer to unload a succession of bullets into a young Black man’s back. It is so much deeper than that. This is no longer about what we think as scholars, it is about how we engage as human beings.

Amidst the nihilism of state violence, I yearned for a sense of community. At its best, organizing resuscitates our collective hope—a hope that is kindled through kindness, kin, and connection.

On March 22, 2018, I encircled my family. My mother and brother drove from the Bay Area to be with us, and together, we headed to downtown Sacramento to join with others who were demanding an end to police brutality.

When I arrived, I was met by people I knew. I marched with colleagues from local school districts, the mayor’s office, local organizers, and religious leaders; it seemed like everyone was in these streets. As a colleague told me, “This is a family reunion.” And a young person turned to me during the march and said, “I never felt my city so united. All the hoods are here—as one.” Inside this unity, I, too, experienced tremendous possibility. The act of mourning politically while chanting unapologetically reassured us that we are here and our existence is a form of resistance. Say his name: Stephon Clark!

The momentum of the protest in honor of Stephon Clark continued to build and we headed to the Kings Stadium. Even though we got locked out of the building, it only inspired us to lock arms and form a human barricade to block the sports event. It’s no time to play, reverberated throughout the crowd. Although the momentum was inspiring, I would be remiss and overly romantic if I did not share the other side of the experience.

While my family and I were immersed in the immense community power, I also stood face-to-face with angry Kings fans and disgruntled drivers who threatened us with violence. A white man who appeared to be in his sixties told me, incessantly, that he didn’t care about what happened: “I am comfortable. I don’t need to care.” His stance was so arrogant and, in my opinion, drenched in privilege and ignorance. Another white male, who looked like he was in his late twenties, was irate. He had served this country in the military and kept yelling “All Lives Matter” less than an inch from my face. An older African American man towered over me at about 6’5” and stood toe-to-toe yelling at me that we must “get out his way” so he could get into the game. He proceeded to announce that I needed to google him so that I would know that he is someone important and of high stature. I told him everyone is important and right now we are here to honor Stephon Clark. He said “I know why you are here,” and shook his head. He proceeded, “it’s for . . . what's his name . . . Trayvon Martin.” Hearing this, another protestor jumped in and proclaimed to the onlookers: “Either you are going to stand with us, and march with us, or you are going to get marched over!”

The divisiveness can get volatile—and quickly. These few comments did not deter us. Nor did they distract us; the naysayers paled in comparison to our embodied justice. Nevertheless, I point them out because we are experiencing heightened divisions (Wright 2017). Stark differences are shaping the ways we experience and interpret life, liberty, democracy, and, as will be underscored in the next section, policing and schooling.

Ecosystems of Interdependence

As personified by the protests surrounding Clark’s murder, we might live in the same city, but experience harshly different realities. When we focus exclusively on just one group (often the problems of the marginalized), it limits our understanding of the intersections of injustice and the ways to effectively address and disrupt it (Watson 2018). Thus, it is critical to explore the interlocking functions of inequity.

In an ecosystem of oppression, oppositions are like codependent realities. Inequality is not just about poverty; inequality lives at the intersection of wealth and marginalization. Racism is not just about People of Color; it is fundamentally about whiteness. This is significant because the ideology of othering shapes our institutional belonging.

As an example, law enforcement officers personify the contradictions of the state. While they protect and serve on the one hand, they also prey and attack on the other. In other words, some of us are policed, while others are protected. A person’s response to law enforcement often depends upon their historical experiences with it.

Schools actually represent a similar duplicity.

Education systems play into a divided social system. Far too often schools and institutions of higher education are esteemed as the spaces where our liberal ideals blossom. The messaging around college—much like education propaganda at large—postulates that these institutions are meritocratic equalizers. Yet as a tool of social reproduction, the schooling system plays a unique role in the creation of haves and have nots. The academy is not immune to these plunders; rather, it also reproduces racism, substantiates oppression, and emphasizes elitism. Although this concept might be uncomfortable, it is not inaccurate.

From a historical perspective, Craig Wilder exposes the ways slavery and its intellectual justification are omnipresent in higher education. He writes, “The academy never stood apart from American slavery—in fact, it stood beside church and state as the third pillar of a civilization built on bondage” (2013, 11). Another scholar, Shaun Harper, contends that universities were born racist and they are still racist. He asserts, “Universities didn’t just all of a sudden become racist. They’ve been racist and exclusive from the start. I wanted to call attention to both the problems and the opportunities. When I say the opportunities, I mean the opportunity to actually force higher education institutions to follow through on their commitment to diversity” (Harper 2017).

Building on Wilder’s and Harper’s work, Leigh Patel challenges us to consider “whether an entity borne of and beholden to coloniality could somehow wrestle itself free of this genealogy” (2016, 4). I ascertain that any entity constructed from the hands of human beings can be altered as well. Institutions greatly impact but do not make individuals. That is to say, human beings make systems, not the other way around. But for this type of critical agency to take root and blossom within the academy, a renewed sense of activism needs to be planted.

As a scholar-activist (Apple 2013; Derickson and Routledge 2015; Sudbury and Okazawa-Rey 2016), I strive to align the community, university, and local schools to advance racial justice, but I struggle and often ask myself, What does it mean to embody research that is in service to social change? I am not alone in asking this question. In a recent article, Warren, Calderón, Kupscznk, Squires, and Su also contend with this idea and offer that community-engaged scholarship utilizes the rigors of research to improve society. They argue that it “represents a partnership between researchers and community change agents designed to create knowledge that helps to advance social justice. . . . It critiques systems of inequality and injustice” (2018, 469). The notion of partnership is critical here. However, I would also underscore the need to be in community with people as change agents ourselves. This type of modality demands a pedagogy of commitment (Watson 2012) and long-term relationships that reach far beyond a traditional workday and impact the ways we live, think, and act. We, too, are implicated as members of this larger community and have a responsibility to seek, demand, and collectively create equitable outcomes.

This sentiment was echoed by the President and CEO of a local foundation in Sacramento during a closed-door session following Stephon Clark’s murder. “The Meadowview community was like a keg of gunpowder waiting to go off,” he told us as he shook his head. He was referring to the severe lack of resources, the disproportionate violence, poverty, and preventable death that plagues a disenfranchised neighborhood. In fact, while protesters were striving to hold the police accountable, Stevante Clark (Stephon’s brother) and some of his other family members were demanding social, economic, and cultural infrastructure and services (Willis 2018).1 I was (and still am) advocating that every child in Meadowview who gets into college receive a full scholarship. Sacramento has the wealth to make it happen, but does it have the will to really seed solutions through resource reallocation? And during this turmoil, what is the role of UC Davis? These are our neighbors. And at Sacramento Area Youth Speaks (SAYS), these are our students.

I now turn to the SAYS model of community-engaged scholarship. Through SAYS I have witnessed, learned, and experienced a form of cultural justice that connects artists, activists, and academics; a collective that ignites the imagination and innovates institutions.

Sacramento Area Youth Speaks

Just a couple of weeks after I graduated with my doctorate from Harvard University, I started at UC Davis as the Director of Education Partnerships in the School of Education. I soon realized that to ground my work in the needs of the local area, I would have to get out of my office. Since I was new to the region, I spent my first two months meeting with various superintendents, teachers, and school leaders.

In each of these encounters, I was hearing similar stories about student disengagement from learning. In particular, everyone kept referencing a literacy crisis across the region: low-income youth of color were not passing the writing portion of the CAHSEE, the high school exit exam. As a former high school teacher and community organizer, and now as a scholar, I wanted to find ways to help the youth of Sacramento succeed. So, I created a flyer for a spoken-word poetry workshop. I circulated it to my colleagues in the schools and asked them to personally invite their students, particularly their so-called hardest-to-reach youth.

I planned for 30 youth to show up; only 5 came.

At this inaugural meeting, these five students were adamant that they needed an outlet for their pent-up anger and aggression. They pleaded for help, saying, “We’re starving for social justice out here, this is not the Bay.” In response, I challenged them to seed the solution. I told them to each bring five friends to the next meeting. One month later, 58 students arrived for the writing workshop.

SAYS was born in the hearts of these radical youth who committed themselves to organize one another and lead the way. These students were clearly engaged and committed to SAYS, but the majority of them were disinterested in school. As a former high school teacher, I was dismayed that their grades were dangerously low while their intelligence was so high. We began to have serious conversations about education. “Why should I care about school?” a student argued with me. “School does not care about me!”

Over the next three months, I continued to hold community-based writing workshops. On many occasions, the sessions ended late and I had to drive students home. Each time I met with families, a pattern emerged that I found disconcerting. To my dismay, families expressed a genuine disbelief that a program from UC Davis was taking an interest in their child. In subsequent conversations, I learned that none of the students or their families had ever come to the university—even though it was less than 30 miles away. UC Davis, as an ivory tower, simply felt out of their reach and beyond their worldview.

Based upon my burgeoning partnership with schools, my close relationship with the Sierra Health Foundation, and a newfound ally in the college’s student affairs office, I was able to secure seed funding to bring 350 youth to UC Davis from 8:00 a.m.–10:00 p.m. for the first SAYS Summit College Day. We held it in May of 2009, when SAYS was just five months old. The theme was “school is my hustle.” Check out the short video from that day: https://vimeo.com/8346909.

Although the summit was geared toward the youth, it seemed to have the greatest impact on the teachers. I received a barrage of phone calls that night and over the weekend from educators who told me that they needed SAYS in their classrooms, immediately. They saw their students come alive through this form of grassroots literacy. Eventually, the dedication and persistence of these classroom teachers brought SAYS deeply into schools from 2010 onward.

Networks of Knowledge

Far too often community-based educators are locked out of schools. To put it another way, many of these people rarely have a formal credential, but if you ask around the neighborhood, they are considered the mentors and real models (as opposed to role models) that young people need. It is their local funds of knowledge and cultural wealth (Moll et al.1992; Yosso 2005), organic intellectualism and cultural power (Gramsci 1992; Hall 1996) that earns them the title of educator among the youth. Even though we need these types of partners inside schools, there are systemic barriers that deter their participation. SAYS developed a model to connect the university and community in a way that would improve learning outcomes. Specifically, the university served as a strategic conduit and training ground that allowed me to hire and place community-based educators (CBEs) into classrooms.

To meet the demand from local teachers to bring SAYS into schools, I went back to my research on community-based educators (Watson 2012). I realized we had a unique opportunity at UC Davis to create a model that brings the community into classrooms. Blending together a grassroots community and youth organizing framework (Ginwright, Noguera, and Cammarota 2006; Skinner, Garretón, and Schultz 2011; Taines 2012; Warren 2005, 2014; Warren and Goodman 2018), I designed a training program that would prepare nontraditional educators from the neighborhood to work alongside classroom teachers.

Now in its tenth year, each cohort partakes in a six-week training program in three core areas: critical pedagogy, social-justice youth development, and literary arts. Once the course sequence is completed, the participants can be hired as part-time university employees at $19.00 per hour. Over the years, we have trained over 30 poet-mentor educators (PMEs). The PMEs are all people of color ranging in age from 18 to 50+. They represent a unique mix of spoken-word artists and activists. The majority grew up in the Sacramento region and attended schools in the area; some even dropped out of the very schools in which they now work.

According to SAYS Coordinator Patrice Hill “Some of us are facilitating workshops at the same schools that expelled us. . . . We are these young people! We sat in the same classrooms, went through the same experiences! . . . It’s a lifelong commitment to the uplifting and empowerment of our babies. This calling is indeed the pedagogy of our lives” (2013).

SAYS hires poet-mentor educators because of their poetic prowess and neighborhood knowledge. Inside their classrooms, inquisitive sharing circles and radical writing activities move students’ narratives into the center of instruction. As a result, decrepit, depressing, under-resourced classrooms become radiated with learning that liberates (Watson 2012, 2013, 2016, 2017).

Over the last decade, SAYS has grown from a writing workshop with five students into a movement that reaches and teaches thousands of students each year. Through the training of community-based poet-mentor educators, SAYS brings the community into classrooms, connects the streets and schools, and fosters connections between neighborhood knowledge and the curriculum. As a result, student attendance has substantially improved, high school graduation rates have increased, and so have students’ grades. While these measures are significant, they are not the soul of the story. The essence of SAYS are the unabashed, truth-telling, multilingual voices of young people who are courageously creating spaces that transform lives.

Project HEAL

For the past two years, SAYS poet-mentor educators have been teaching a full-time elective class called Project HEAL (Health, Education, Activism, and Leadership) at Burbank High School. Burbank is just a couple of blocks from Stephon Clark’s family home. Inside the SAYS class, students’ lives are the tableau of inquiry; life is a primary text (Watson 2017).

Today, the students are sitting at four large, rectangular tables that have been pushed together—to form what feels like an expansive kitchen table. It is 5th period and the teenagers start to shuffle into the room, even before the bell has officially rung. “Did you hear that there is a protest at the capitol at 1:00? I want to be there. But I came here,” a 10th-grade student shares with the group. The dialogue meanders and lands on the word legacy. “Stephon Clark did not get to fulfill his legacy,” a student chimes in. The SAYS instructor, an African American woman in her mid-thirties, discusses “dying of unnatural causes” and then asks the young people, “What is your legacy?” This question penetrates through the classroom and leaves the conversation still, and silent.

Reminiscent of Yosso’s (2005) community cultural wealth framework, this theory becomes practice inside SAYS. The instructor proceeds to prod and writes on the board intergenerational curses/struggles on the left and generational wealth/strengths on the right. In rapid succession, the students share a litany of responses out loud. The SAYS instructor is writing each word on the whiteboard.

Sample of the statements on the board:

Generational curses/struggles:

|

Generational wealth/strengths:

|

When the ever-present dangers of trauma weigh heavily on a person’s life, conceiving of a legacy larger then oneself can feel overwhelming. Cognizant of this dilemma, the SAYS instructor carefully scaffolds the lessons to create a word palette of communal and personal strengths and struggles. From this prompt, students begin to pull words from the board and start to write in their journals. The shooting of Stephon Clark is ever-present; the ills of oppression suffocate legacy.

Sample from a student’s journal entry:

Too many crimes in my city.

Always hearing gunshots, crying for pity.

Hoping and wishing things would get better, but that’s like a dollar to fifty.

Cops keep killing my loved ones.

No justice or peace for anyone.

Scared to walk anywhere thinking that it might be your last.

Praying and praying hoping to get passed.

The struggles we are all going through.

Man, when are they going to get it?

Sample from a student’s journal entry:

Ghetto

I call it home,

Next to section eight,

Where most people see bullets penetrate.

Lost souls due to jealousy,

Lost homies to the grave n’ penitentiary,

Goddamn this life is hell.

A beautiful struggle in the background,

Luxuries in the lives we live,

Fast life, we take, but not give.

The students’ testimonies are hauntingly similar from one generation to the next. As another example, in 2012, the rapper The Jacka performed at the SAYS Summit College Day at UC Davis.

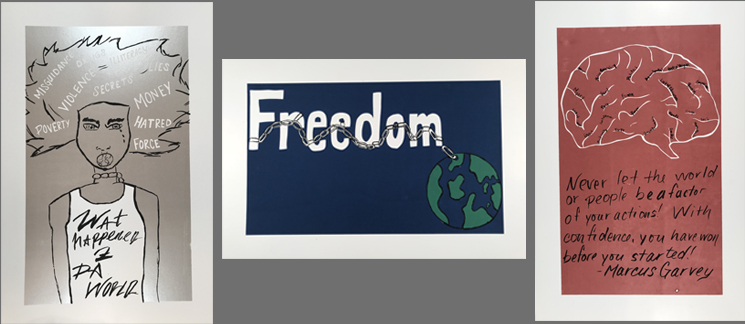

Approximately two years later, The Jacka was shot and killed in Oakland, CA. To honor his passing, at the SAYS Summit College Day in 2015, poet-mentor educator Denisha Bland led the students through a workshop called What Happened to the World? based upon one of Jacka’s albums. During the workshop, students worked in crews to design posters that answered this overarching question. We then passed these hand-drawn posters onto Chicanx Studies students at UC Davis who brought them to TANA and turned them into posters.2 Subsequently, the posters were handed out to students and teachers a year later at the 2016 SAYS Summit. These posters, and others created through this partnership, adorn the walls of classrooms throughout Sacramento as well as at the SAYS Center in Del Paso Heights.

Sample of the SAYS youth posters: What happened to the world?

In the first picture, the person is crying and the world is censoring their voice (picture of the world over their mouth). A chain is wrapped around his throat and inside the mind the following words are depicted: misguidance, poverty, violence, money, hatred, force, secrets, lies, drugs, and illiteracy.

In the middle drawing, the students drew a broken globe that is chained to the word Freedom. According to the students in this particular crew, they wanted to depict that the lack of freedom is oppressing the world and literally tearing it to pieces.

In the final poster on the right, the students from the Marcus Garvey crew utilized one of his quotes at the bottom (“Never let the world or people be a factor for your actions. With confidence, you have won before you started.”) This quote serves as the foundation of the artwork and sits in juxtaposition to a brain filled with words of pain, such as lack of education, politics, guns, money, and police brutality.

This is not art for art’s sake. When I first began SAYS, students were prolifically analyzing the ailments of inequality, the injurious nature of miseducation, and the oppressive nature of policing in their neighborhoods. A decade later, we buried Stephon Clark. Although he is not the first person killed by the police in Sacramento, we are at another defining moment as a society, as a university, and as the capital of California. Will he be the last?

Cultural Responsibility

If we cannot make the university our own, how will we make it a nurturing intellectual environment for our children? At SAYS, we profess that it is not a crime to be who you are. If that is true, then the fullness of our humanity should shine, unapologetically, wherever we are. As Audre Lorde teaches, "When I dare to be powerful, to use my strength in the service of my vision, then it becomes less and less important whether I am afraid" (2007). Our consciousness and commitment to the cause (e.g., hands up, don’t shoot) does not stop when we enter into an academic environment. Quite the opposite. Scholar-activism propels us to connect the personal, professional, and political. Community and belonging is not defined or determined by man-made borders or neoliberal edifices. Wherever we be, we seek to manifest ourselves completely, and, according to SAYS, poetically.

At this year’s UC Davis Equity Summit, I spoke about poetic possibilities. I shared that in many ways, we are living in the haiku era—a unique poetic time. Now why would I say this? Well, this is a day and age when you need a quick tweet, snap, or crackle pop to go viral. To get the word out, a person might become famous through Instagram like Cardi B or take over a presidency (#45, who talks and tweets and thinks in 45 words or less). If we are living in the time of the poet, what is it you want to say?

The essence of poetry is not words, it is activism. Again, it is Audre Lorde who reminds us that “poetry is not a luxury,” it is an action of reclaiming oneself in relation to the world. Self-expression allows the soul to speak; this is irrespective of cultural nuances, language, or loudness (Watson 2013). June Jordan posits that poetry is a medium for telling the truth; poetry reaches for maximum impact with minimal words; and, most importantly, poetry is the highest art and most exacting service devoted to our most serious and most imaginative deployment of verbs and nouns on behalf of whatever and whoever we cherish. In this way, poetry is not a hiding place, it is a finding place. As Freire contends, critical literacy practices are a vital component of self-actualization and agency. “Human beings,” he writes, “are not built in silence, but in word, in work, in action-reflection” (1970, 69).

Thus, there is a recurring utterance that between what is and what could be, there is poetry. Poetry lives at the nexus of legacy and prophecy, pain and hope, death and life. At SAYS, we strive to lift as we climb through a process of collective empowerment. This includes places like UC Davis.

The SAYS story is a narrative of resistance and cultural justice. To help us understand our own work, we partnered with Dr. Natalia Deeb-Sossa (UC Davis, Chicanx Studies) to develop a photovoice project. Since we navigate very different places (university, communities, and schools), testimonios provided a platform for us to embody and codify some of the challenges of community engagement and scholar-activism. Although we often use our words as weapons, fototestimonio painted a picture of the paradoxes we experience as we align ourselves as artists, activists, and academics within and beyond the university.

The visual images capture how our learning unfolds through interaction, through the sharing of time, space, and ideas. They highlight that to be a public intellectual and scholar-activist is to wrestle with the tensions and contradictions between literature and life, theory and practice, being and becoming.

The photographs, especially those taken in the community, remind us that cultural keepers maintain and restore legacies of resistance within and beyond the walls of the institution. Culture is everywhere and it’s alive; as the saying goes: “Cultura es vida.” Culture is the people. Storytelling and imagery are forms of cultural keeping. A person does not need a degree to share a life experience nor take or interpret a picture.

It would be too simplistic to delineate clear-cut polarities between the university and the neighborhood. There are benefits to both institutional settings; the problem is that they seem so far away from one another—like different worlds inhabited by different kinds of people. For SAYS, we intentionally and strategically exist in both locations as bridge-builders and cultural keepers of legacy and liberation.

As an act of healthy disruption, SAYS continues to grow in multiple directions—from a single tree into a forest. We operate a community center in Sacramento where students get free tutoring from UC Davis undergrads, we facilitate in-school and after-school writing and performance workshops, we organize the largest youth poetry slam competition in the region, the city-wide Youth Poet Laureate competition, the MC Olympics, and we continue to expand the Project HEAL elective courses. At the university, we are also gaining traction with our SAYS warrior scholar internship program for undergraduates, the SAYS open mic nights (in partnership with the Mondavi Center), and various courses that I teach that focus on educational equity and community-engaged scholarship. It is noteworthy that every May we now bring 1,000 middle school and high school students from across California to experience a Tier-1 Research University through the lifeline and vision of SAYS. From 8:00 a.m. until 8:00 p.m., we skillfully curate a higher educational experience that is unparalleled; it is infused with youth culture, critical street literacies, and hip-hop. We show the youth—the majority of whom have never stepped foot onto a college campus and who are struggling in school—that they can move from being high-risk to and through higher education. We strive to make these students feel at home in a setting that for generations has excluded them and their families.

We invite you to take a look inside the social justice movement that is Sacramento Area Youth Speaks: https://vimeo.com/135921332.

Radical Reimagining

If UC Davis wants to become a premiere university of diversity and community, what actions fortify this ideal? 1. Since people are the power of institutions, it takes real-life equity warriors who are supported, encouraged, and empowered to enact a social justice pedagogy that revivifies, reimagines, and reconfigures higher education. 2. The function of higher education has some of its own soul-searching to do. People come from all over the world to gain expertise in a specific major and learn the science of their discipline. But while they are with us, are they learning more about themselves, their communities, and perhaps most importantly, about each other? Does coursework explicitly address the vestiges of racism and white supremacy or does college reproduce status?

Given the ethos of our new Chancellor, I am optimistic that UC Davis could go where none have gone before (Star Trek); we could choose loyalty to the force that connects us (Star Wars); and we are poised to reclaim our humanity by addressing and moving away from the sicknesses of whiteness and colonialism (The Black Panther). Although we are not in a movie, we are all actors with tremendous capabilities within and beyond a job title or positionality. If we are the people, then how do we come together?

In my own journey, I have found that staying present and locally committed is challenging, but absolutely essential. Showing up—not just theoretically, but practically—can be inconvenient and time-consuming, yet I contend that as scholar-activists and community-engaged researchers, it is fundamentally about presence. The presence of mind to know what is actually going on beyond the academic bubble and beyond the silos of our disciplines, and the long-term responsibility to put in the work—intellectually, physically, and fiscally.

SAYS is a movement that sprouted organically at UC Davis. It was nurtured by the youth of Sacramento who committed to creating platforms for their voices to be heard. And for many years, SAYS existed almost entirely in schools and in the community. I could walk onto a school campus and ask rhetorically, If you got something to SAY? And the students would shout, SAYSomething! Because of our #schoolismyhustle motto, during school-wide assemblies, I would get on the mic and just utter the word school and the entire auditorium would retort back: hustle. A decade later, the SAYS pedagogy is growing within the academy, our networks are expanding, and our rituals of resistance are taking root.

At this new nexus, the artist, activist, and academic come together on a path towards cultural justice. As Horton and Freire (1990) teach us, we make the road by walking. Words without work is like a theory without practice. Systems-change for social justice takes time, consistence, direction, purpose, and love. It also takes the soulful work of imagining.

The university, community, and schools are all spaces to say her name. To say his name. From New Bedford to Sacramento, we are unlocking legacies by remembering the lives we have lost. We carry our ancestors with us—inside us. We are preeminent warrior scholars on these streets and in these systems, who are striving to create intellectually, study differently, and live more holistically.

So long live Stephon Alonzo Clark. And yes, his initials spell out SAC.

BeLonging

Our Legacy is

Louder than the ivory tower

Older than borders that divided us into being something we are not

Somehow we forgot

To put tongue in rightful place

Use words to transform spaceHear we be

From privilege and poverty

Accepting no praise or pity

Just mouth-full of poetrySo courageous

We transcend the cage

Unapologetically brave

Destroy the master and the slave

Sages on stageCan you hear the rewind?

That reminds us to reclaim repurpose renew

The UniVerse is filled with these eternal truthsVowel breathe and spit // repeat // vowel breathe and spit

Until we be

The future that

calls us forward.

Appendix A: SAYS Guidelines

SAYS Guidelines

1 Mic

Loud-N-Proud

Step Up . . . Step Back

Freedom of Speech . . . With Propriety

Create Community . . . No Snitchin

Standard Is Yourself: Be You and Do You

Respect . . . Self, Others, and the Space

Patience, Perseverance, Participation, and Above All: Love

Below is verbatim how I describe the SAYS Guidelines.

1 Mic: Nas popularized this sentiment, but we use it every time up in here. If one person is speaking, we listen. It’s that simple.

Loud-N-Proud: When you do speak, own your words and speak so that we can really hear you. Raise the roof with the power of your voice.

Step Up/Step Back: If you like to run your mouth like I do, make space for someone else to speak by keeping your mouth shut once in a while. But if you are shy, we genuinely want to create a space for your voice to be heard. So, take a risk and share what you’re thinking. Sharing is caring and a closed mouth can’t get fed.

Freedom of Speech . . . With Propriety: Speak your truth, but remember someone is always listening. Be conscious of what you say and how you say it. Even the grimiest rappers have radio versions these days, so recognize that there is a time and a place for everythang.

Create Community/No Snitchin: Whatever is said in this room, stays in this room . . . No playin.

Standard Is Yourself: Be You and Do You: Raise the bar for yourself and challenge yourself to do more and be more. And if that fails, let your haters be your motivators.

Respect . . . Self, Others, and the Space: Aretha like to sing it, and we are going to try and live it: R-E-S-P-E-C-T/Find out what it means to me/R-E-S-P-E-C-T.

Patience, Perseverance, Presence, Participation, and Above All: Love: Changing the way we teach and learn is hard work and we need to have patience for one another and for this process. But no matter the hurdles, our perseverance and our participation is our collective power. We will make this road by walking, but please remember that this journey is fortified with love, hope, and a commitment to see you grow. I love you. You might know it now, but you can see it in my eyes. Real talk: I love you!

Okay, are there any questions, comments, concerns, or criticisms? I know y’all want to change at least one of these guidelines. They belong to you, let’s talk about it. . . .

Appendix B: SAYS Writing Assignment Sample

Acceptance Workshop Summary

Twelve steps to getting to know a deeper part of our selves and each other:

Step 1: First put “Acceptance” on the board and ask the students: What comes to mind when you think about Acceptance? [Probes: What does it take to be accepted? What does it take for you to accept someone? What does it take to be accepted at school? In your family? Your neighborhood?] Write all responses on the board.

After the board is full, explain that the students created a collective definition of acceptance and a word palette. Read out loud all of their responses that are on the board.

Step 2: Tell students to pick six responses from the board that resonate with them, and write them down on their pieces of paper.

Step 3: Ask them to circle three that appeal to them the most.

Step 4: Ask them to cross those three out.

Step 5: Tell the students the challenge is to use the three remaining words/lines in the upcoming free-write exercise.

Step 6: Explain the rules of the free-write: A hand in motion stays in motion—keep writing! Don’t think too hard, if your mind wanders, it’s okay, but write down your thoughts in real time. For example, if your leg starts to itch, don’t scratch your leg, write about your leg itching. Ask them if they are ready to begin.

Step 7: Finish the following sentence and keep writing using the three words/phrases:

I AM NOT WHO YOU THINK I AM . . .

Have students write continuously for three to five minutes. Pencils down.

Step 8: Have students draw a line on their paper to prepare for the next prompt. Pencils in the air.

Step 9: Write down three specific moments that have made you into the person you are today. What was the year, season? What made this experience so significant? Take us there. Write.

Step 10: Have students draw a line on their paper to prepare for the next prompt. Pencils in the air.

Step 11: Write down three questions in which the answer is you. Be sure to write the question and your full name for each. For example:

1. Whose mom would sing angels into the room when she put her baby girl to sleep each night? Vajra Mujiba Watson

Step 12: Go over the SAYS Guidelines and then ask participants to share what they wrote. Anyone sharing must read what they wrote verbatim (no paraphrasing) and they must read all three sections all the way through.

Notes

1 This is another moving video about the aftermath of the killing of Stephon Clark and the families' demand for resource centers.

2 Taller Arte del Nuevo Amanecer (TANA) is a collaborative partnership between UC Davis, Chicana/o Studies, and the greater Woodland community. TANA cultivates the cultural and artistic life of the community, viewing the arts as essential to a community's development and well-being.

Work Cited

Apple, Michael W. 2013. Can Education Change Society? New York: Routledge.

Derickson, Kate Driscoll, and Paul Routledge. 2015. “Resourcing Scholar-Activism: Collaboration, Transformation, and the Production of Knowledge.” Professional Geographer 67 (1): 1–7.

Freire, Paulo. 1970. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Bloomsbury.

Ginwright, Shawn, Pedro Noguera, and Julio Cammarota, eds. 2006. Beyond Resistance! New York: Routledge.

Gramsci, Antonio. 1992. Prison Notebooks. Vol. 2. New York: Columbia University Press.

Hall, Stuart. 1996. “Cultural Studies and Its Theoretical Legacies.” In Stuart Hall: Critical Dialogues in Cultural Studies, edited by David Morley and Kuan-Hsing Chen, 261–274. New York: Routledge

Harper, Shaun R. 2017. “Fighting Racial Bias on Campus,” interview by Sandra Stevenson, New York Times, February 2.https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/02/education/edlife/fighting-racial-bias-on-campus.html.

Hill, Patrice. 2013. Interview, Grant Union High School.

Horton, Miles, and Paulo Friere. 1990. We Make the Road by Walking: Conversations on Education and Social Change. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Jordan, June. 1985. On Call: Political Essays. Boston: South End Press.

Lorde, Audre. 2007. “Poetry Is Not a Luxury.” In Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches by Audre Lorde. New York: Random House.

Moll, Luis C., Cathy Amanti, Deborah Neff, and Norma Gonzalez. 1992. “Funds of Knowledge for Teaching: Using a Qualitative Approach to Connect Homes and Classrooms.” Theory into Practice 31 (2): 132–141.

Patel, Leigh. 2016. Decolonizing Educational Research: From Ownership to Answerability. New York: Routledge.

Skinner, Elizabeth A., Maria Teresa Garretón, and Brian D. Schultz. 2011. Grow Your Own Teachers: Grassroots Change for Teacher Education. New York: Teachers College Press.

Sudbury, Julia, and Margo Okazawa-Rey. 2016. Activist Scholarship: Antiracism, Feminism, and Social Change. New York: Routledge.

Taines, Cynthia. 2012. “Intervening in Alienation: The Outcomes for Urban Youth in School Activism.” American Educational Research Journal 49 (1).

Warren, Mark R. 2005. “Communities and Schools: A New View of Urban Education Reform.” Harvard Educational Review 75 (2): 133–173.

. 2014. “Transforming Public Education: The Need for an Educational Justice Movement.” New England Journal of Public Policy 26 (1): 11.

Warren, Mark R., José Calderón, Luke Aubry Kupscznk, Gregory Squires, and Celina Su. 2018. “Is Collaborative, Community-Engaged Scholarship More Rigorous Than Traditional Scholarship? On Advocacy, Bias, and Social Science Research.” Urban Education 53 (4): 445–472.

Warren, Mark R., and David Goodman. 2018. Lift Us Up, Don't Push Us Out! Voices from the Frontlines of the Educational Justice Movement. Boston: Beacon Press.

Watson, Vajra. 2012. Learning to Liberate: Community-Based Solutions to the Crisis in Urban Education. New York: Routledge.

. 2013. “Censoring Freedom: Community-Based Professional Development and the Politics of Profanity.” Equity & Excellence in Education 46 (3): 387–410.

. 2016. “Literacy Is a Civil Write: The Art, Science, and Soul of Transformative Classrooms.” In Social Justice Instruction: Empowerment on the Chalkboard, edited by Rosemary Papa, Danielle M. Eadens, and Daniel W. Eadens. New York: Springer International Publishing.

. 2017. “Life as Primary Text: English Classrooms as Sites for Soulful Learning.” The Journal of the Assembly for Expanded Perspectives on Learning 22 (Winter): 6–18.

. 2018. Transformative Schooling: Towards Racial Equity in Education. New York: Routledge.

Wilder, Craig Steven. 2013. Ebony and Ivy. New York: Bloomsbury Press.

Willis, Kiersten. 2018. “Stevante Clark’s Aunt Passionately Fires Back at Criticism Over His Behavior Since Stephon Clark’s Death.” Atlanta Black Star, April 2. http://atlantablackstar.com/2018/04/02/stevante-clarks-aunt-passionately-fires-back-criticism-behavior-since-stephon-clarks-death/.

Wright, Robin. 2017. “Is America Headed for a New Civil War?” New Yorker, August 14, 2017. https://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/is-america-headed-for-a-new-kind-of-civil-war.

Yosso, Tara J. 2005. “Whose Culture Has Capital? A Critical Race Theory Discussion of Community Cultural Wealth.” Race Ethnicity and Education 8 (1): 69–91.