Abstract

In times of crisis, unforeseen factors can emerge in conducting public scholarship and research, especially in marginalized communities. Given the current political climate, it is imperative we bring attention to how crisis creates barriers which can hinder, obscure, and complicate public scholarship, and how crisis is endured by the communities with whom we seek to collaborate. This paper reflects on the experiences of three 2017 Mellon Public Scholars: Mayra, who works with Latino farmworker parents of children with special needs; Roy, who investigates the role of citizenship/legal status in the lives of undocumented Asians/Pacific Islanders; and Alana, who seeks to identify how the homeless population is and isn’t being served by a county’s food bank’s services. Through this discussion we hope to make more salient the challenges of doing public work in underprivileged communities, so that future scholars can better prepare for the dynamic situations they will navigate as they tackle their own projects.Introduction

Fear, anxiety, outrage, anguish, and disgust have beset the public in the last couple of years. The election of United States President Donald J. Trump has highlighted and intensified frictions and inequalities nationally and globally. We live in a time of crisis defined by intense instability, difficulty, troubles, insecurity, and danger. Politics are greatly polarized, dividing the public and agitating more hate and hostility. White supremacy has flared up, fueling fierce white US nationalism. Bigotry and violence against Muslims, Blacks, immigrants, LGBTQ+ groups, and other targeted groups has spiked. Misogyny and sexual assault are normalized. Trump impulsively terrorizes the world with nuclear war threats. War, increased militarization, and more violence are proposed as solutions to a myriad of problems. Neoliberalism and corporatocracy have consolidated power and wealth in the hands of a few elites. Post-truth politics rampantly deceive and spur chaos, undermining a sense of democracy and trust in political institutions. Scientific knowledge is disparaged. Threats of anthropogenic climate change doom us, yet are denied and worsened by those in power. Precarious living conditions are intensified as we see through the housing crisis, health care crisis, and so forth. While structural forces have sedimented the current situation over years, Trump’s election has surely transformed the social and material world. How we perceive this crisis, nonetheless, across uneven spaces of power and privilege, is configured in its situated geographies and histories. We reflect on how the Trump era has created a heightened sense of crisis which has galvanized scholars within our own liberal academic spaces, triggering us to study how the supposed inherent troubles and insecurities are experienced in communities not too distant from our university where we carried out our projects.

As scholars committed to producing timely and meaningful scholarship that approaches these pressing issues, we raise the question, What does it mean to do public scholarship during a time of crisis?

The three of us were each selected to be members of the second cohort of Mellon Public Scholars (MPS) from the University of California, Davis. Drawing from our own individual experiences as scholars across three different sites in California, we share our reflections on how the current crisis mattered (or not) to the public with whom we worked, and how it impacted the process of doing such scholarship. The MPS program consists of a select cohort of graduate students across the arts, humanities, and humanistic social sciences who learn about the intellectual and practical dimensions of collaborating with members of a public (outside the academy) through scholarship. The program supported our development of a community-engaged project under the supervision of a faculty advisor. The main purpose of this program is to bridge the university with the public. An objective of MPS is to build spaces for dialogue and inquiry regarding public scholarship while shedding light on the value of this kind of work in the academy.

By looking at how vulnerable groups experience everyday life and some of the troubles that come along with it, we emphasize how crisis is relational. In particular, we pay attention to the extended and pervasive temporalities of the hardships and structural violence they have confronted. We bring up ethical issues that come up as we work with communities who experience the harsh realities of living in the margins. We assert that the current crisis did not emerge from a stable, equal, non-troubled world. On the contrary, this crisis emerged in a society already struck with vast social inequality, an insatiable capitalism that has produced clashes between classes, legacies of (neo)colonialism, and human-accelerated environmental deterioration over the last two centuries. We question how these widespread “crises” are experienced in the periphery, rather than in the center where we often find ourselves as scholars.

Mayra: Ordinary Troubles among Farmworkers in California’s Salinas Valley

Roy: At the Intersection of Legal-Status Issues and Public Scholarship

Alana: The Collision and Intersection of Crises

Mayra: Ordinary Troubles among Farmworkers in California’s Salinas Valley

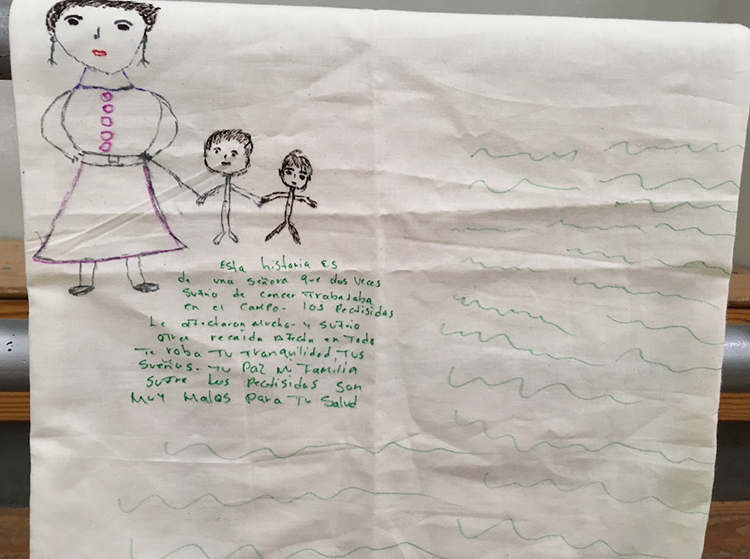

A couple of years ago, I met Estrellitas, a parent support group for children of special needs that formed as a response to the lack of resources in their small town of Gavilan. They were a relatively small and nascent group who met regularly, invited guest speakers, built community, and organized various family events. All the members were Mexican migrant farmworkers, both Spanish-speaking mestizos and members of indigenous groups. Nearly all were women. The group wanted to share their stories more broadly in order to bring visibility to the atypically high rates of disabilities among their children and the absence of resources and services in their communities. As part of my MPS project, I worked closely with Laura and Teresa, both mothers of children with autism, in setting up their organization’s website and social media, as well as organizing the annual free conference for families of children with disabilities who live in the southern region of the county. Collaborating with Laura, Teresa, and other members of Estrellitas, sharing conversations, and observing how they continuously confront structural hardships in their ordinary lives, and work to serve and transform their community has helped me grasp their worldviews and become more sensitive to the matters they care about.

I have travelled the 400-mile round-trip between Gavilan, a small Latino-majority agricultural town in the deep Salinas Valley, and my hometown of Davis many times. I have moved in and out of different realities and tried to conceptualize what I saw in the field with what I learned in the academy. In an effort to produce scholarship that is attuned and responsive to this time of crisis, I question what it means to do public scholarship in times of political and environmental crisis. There is a sense that although times are extraordinary and temporary, there can still be a sense of hope. Rather than taking for granted the scope and form of the urgent crisis that has recently surfaced through Trump’s rise to the presidency, I ask, What does this crisis look like within the community of my project? How do we render perceptible troubles that are invisible, silent, and difficult to capture? How do we consider communities’ experiences with intense difficulties, injustices, pain, and suffering over a longer temporality beyond the transience suggested by the invocation of “crisis”? And ultimately, how do we look for hope amid crisis?

The day I met Laura, she expressed to me her belief that the high incidence of children with special needs in her town was caused by agricultural pesticides. As part of a silent, invisible, and dispersed socioenvironmental crisis that primarily affects farmworkers and their children, the residents of Gavilan are continuously exposed to the tonnage of pesticides dumped in the Salinas Valley. Although pervasive and insidious, this toxic exposure is part of a slow violence that lacks the spectacle or explosiveness of a catastrophic or critical event (Nixon 2011). Last year was critical for the regulation of chlorpyrifos, a neurotoxic insecticide linked to autism and learning disabilities (Marks et al. 2010; Shelton et al. 2014) heavily used in the Salinas Valley to “protect” the high-value crops of Monterey County’s $9 billion agro-industry (Langholz and DePaolis 2015). After the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) under Trump refused to ban this chemical, in July 2017, farmworkers and activists rallied for a state ban at the California EPA, but members of Estrellitas could not attend. Doing community-engaged scholarship on environmental justice, I was hoping Estrellitas would join and speak for themselves on how they have been affected, and potentially network with other organizations, activists, and families with children with disabilities across the state. Laura was interested in participating, but she let me know it was too difficult for her and other parents to deal with. Among the many complications she listed, she was worried about finding proper care for their children with disabilities or diverse behaviors. Furthermore, while other Gavilan residents have organized for further pesticide regulations near their city’s schools, Estrellitas has not been involved with those projects. They do, nonetheless, continue to meet and support each other in their daily challenges to care for their families with their limited resources, hoping to make a difference.

Povinelli, who is “interested in forms of suffering and dying, enduring, and expiring, that are ordinary, chronic, and cruddy rather than catastrophic, crisis-laden, and sublime” (2011, 13) helps me engage with the violence folded into the ordinary burdens in zones of dispossession. Moreover, along with other feminists (Stein 2004), I also noticed that it is working-class women of color, like the members of Estrellitas, whose unseen and devalued labor involves carrying the brunt of structural and environmental violence by caring for the well-being of their families and communities. Our public scholarship should appreciate the undervalued work and alternative ways in which unevenly burdened communities are already confronting their troubled lives—particularly during prolonged “crisis.” Thus, it is important to question how we define “community engagement” and “activism” to bring social and environmental justice, and to work to raise the unheard voices who are continuously exposed to harm, overwhelmed and exhausted with ensuring their own survival.

Yet, I expected Estrellitas to have engaged more actively with the evident “crisis” surrounding Trump’s election. On January 21, 2017, I joined over a hundred local community members at the Estrellitas conference in Gavilan, while millions worldwide participated in the historic Women’s March a day after Donald Trump’s presidential inauguration (Jamieson, Slawson, and Khomami 2017). While elsewhere protesters aimed their outrage towards Trump’s politics and victory, to my surprise, the conference went on as planned, with no mention of the ongoing political climate. The topics discussed revolved around practical knowledge for families, such as legal rights for children with disabilities, technologies best suited for their children’s needs, immigration, and health. Given the direct connection between the federal government’s environmental and immigration policies and the experiences of the group, I was befuddled by the group's lack of engagement with the national political events unfolding—which, in my view, were difficult to ignore.

As I attempt to understand the group’s silence around national politics that day, in contrast to the frenzy erupting throughout the liberal media, academy, and my social spaces, I pause to think about “crisis” as relational, and how history shapes people’s subjective experience of the duration and intensity of troubled times. Working with this farming community for several years, knowing their broad history, and as a Mexican myself, I wonder how the layering of structural violence may have contributed to the silence regarding Trump’s election and national politics. I think about their precarious lives as farmworker migrants from Mexico, the long history of colonialism, state neglect, and violence in Mexico—particularly in Oaxaca, the most marginalized state where most of these migrants come from (CONEVAL 2015). Similarly, I wonder if a diminished or threatened sense of belonging to the US—a country that has exploited their labor and treated them as dispensable, excluded them for being undocumented, and discriminated against them for their indigenous and Latino ethnicities—shaped their engagement in national politics. In other words, the subaltern experience of those in the periphery is not represented by the outspoken fear and fragile sense of insecurity and danger I witnessed and felt with others in more privileged spaces of power. Furthermore, Laura told me she avoided expressing joy at the conference as a sign of respect to the recent pain and loss the community suffered. A couple of weeks before the event, a leading group member had suffered a serious stroke. Another community member passed away in an accident, leaving her children with special needs behind. In this way, Laura prompted me to be sensitive to the other troubles and pains that mattered in that space that day, rather than those I had assumed had mattered, coming from a more comfortable and privileged position.

At this year’s 2018 conference, which again coincided with the Women’s March, Laura invited Judith, a local political representative, to speak at the event. In her position, Judith has fought the use of toxic pesticides around her community and has been active against the use of chlorpyrifos. Laura asked Judith to speak on any topic. “Anything but politics. Things are so ugly, and I don’t want her to talk about politics. I want people to be happy this year.” Although Judith could have talked about one more "ugly” thing, this year Laura wished for her community to feel joy and cheerfulness amid adversity and nasty political times. I like to think that people were happy, not only because they danced and sang, but because they transformed these ugly times into a place that fostered inclusion, equity, solidarity, and perhaps hope.

In attempting to produce scholarship in this time of crisis, I have learned to not anticipate what a “crisis” looks like in my field. In order to analyze the interrelation between power, politics, space, and time, it is useful to think of the relations that hold things together rather than imposing notions from the center. Slowing down, looking carefully from within, making time to know the interrelated histories, places, peoples, and concerns that matter is “critical.” Even in a time of crisis, it is important to consider how in doing public scholarship that aims to render injustices perceptible and bring about change, we must use caution to not add more burden or labor to those most affected, and to be sensitive to the lived experiences of pain and suffering. Lastly, doing public scholarship in a time of crisis matters for its potential to help us find hope for better futures and alternative worlds.

Roy: At the Intersection of Legal-Status Issues and Public Scholarship

As part of the second cohort of the MPS Program, I conducted a public works project with Migrante Napa-Solano (or more affectionately known as Migrante 707), a community organization working on the issues facing the Filipinx diaspora based in Northern California. I proposed creating an archive of oral histories from undocumented Filipinx migrants, whose stories are largely left out of the narrative on undocumented immigrants in the United States. Asians and Pacific Islanders (API) constitute more than 10 percent of the undocumented population in the United States (Teranishi, Suárez-Orozco, and Suárez-Orozco 2015), with Filipinxs making up one of the largest subgroups (Ramakrishnan et al. 2017). As such, I believed it was extremely important not only to document their lived experience, but also to create a tool which could be used to advocate for their rights. These oral histories could also be used to let other undocumented Filipinx migrants know they are not alone, and that there are others out there sharing the same struggles.

I knew from the outset this would be a difficult project. After all, how would I convince a person who has spent their life shying away from direct attention to not only let me, who was for all intents and purposes a complete stranger, conduct an interview and share the intimate details of their lives? What I didn’t anticipate, however, would be the additional difficulties stemming from the political climate which directly affected the people to whom I was reaching out for my project. On September 5, 2017, United States Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced the end of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrival (DACA) Program, an Obama-era executive order which provided a renewable two-year deferment of deportation to undocumented individuals who migrated to the United States as minors. After this announcement, many of the individuals with whom I was scheduled to conduct interviews asked to withdraw their participation from my project, noting that they no longer felt comfortable revealing more information about themselves when the news and media outlets kept pushing the anti-immigrant narratives espoused by the federal government.

Let it be said that none of the people I was communicating with at the time actually had the protection of DACA. But despite the fact that for these individuals the end of the DACA program had no direct bearing on their lives, they still felt (as I might point out, legitimately so) attacked. Despite not being United States citizens, (and potentially because of their status as noncitizens), they were well aware of the anti-immigrant stance taken by the White House, and reacted accordingly by expressing hesitance to participate in the project. However, I felt that it was extremely important to collect their narratives, especially given the scarcity of information concerning undocumented Asians and Pacific Islanders. Further complicating matters is the additional dimension of my own positionality. I am an undocumented migrant of Filipinx descent. When I set out to do this project, I desperately wanted to be the one to tell our story—and beyond that, to also have the chance to tell my own story. Sharing certain aspects of my identity as an undocumented Filipinx scholar enabled me to reassure my interviewees that to a great extent, I understood what they were going through. I knew of the gravity of their situation, and beyond that, I knew of the consequences should I fail to uphold my end of the bargain to protect their identities as they participate in my work. Ultimately, it required a bit of reassurance regarding my stance on confidentiality issues. By reiterating my professionalism and my diligence as a researcher and empathizing with their experience, I instilled in them the confidence that I would protect their identities. They would not be exposed through this project.

The point of this reflection, though, is not to go into the intricate details of my MPS project. Rather, it is to highlight the additional challenges that publicly oriented scholars have to overcome as they pursue this type of work—challenges which are not only made more salient, but are also realized in times of crises. Despite the identity I share with the undocumented Filipinx community, I failed to recognize the magnitude of the disparity between my experience and that of those who I sought to work with, and the differences soon became apparent. I had the advantage of being protected by DACA, while many of those I interviewed were not eligible for the DACA program. I have an extremely supportive family—a privilege which enabled me to pursue an American education—while for many of the participants it had been years since they had spoken to their family back in the Philippines. I grew up in the United States, in contrast to those I interviewed who migrated to the US later in their adulthood. In a time of political crisis, I had options and they did not.

Many public scholars conduct work which involves communities already in the margins of society—those who have slipped through the cracks and find themselves without a safety net. In this case, I worked with a group of immigrants, specifically those who identify both as undocumented and as Filipinx—in a sense, those who live in the margins of the margins of society. Filipinxs have been largely overlooked in the discussions surrounding undocumented immigration, but the current political crisis has changed the dynamic of the conversation to one in which they feel they are being targeted. Undocumented immigrants are living in a time of extreme crisis—one in which an organization as large and as powerful as the federal government has them in its sights. And while these executive orders and anti-immigrant policies may not name any particular individual as their target, their impact can be felt at a personal level for those who are the least likely to have the tools and ability to fight back.

So what does this mean for public scholarship? First, we must understand that these times of crisis are not happening to us in the same ways in which they are happening to the people with whom we work. Even for myself, what emerged from this experience was not only a reification of the necessity of community-based scholarship for and by those who themselves identify as part of a marginalized group, but also a new awareness of my own “in-between-ness,” of my role as a scholar with my intersectional identity. I have the privilege of being a scholar, I have the ability to express myself in my writing, and I have the opportunity to have my voice heard in arenas which others might not. As academics, this privilege enables us to live and work in positions of relative stability—positions which, to a certain extent, protect us from the shifts in the political climate. Marginalized and underserved communities, however, have no such protections. The precarious nature of their lives make them vulnerable to the subtle (and not-so-subtle) changes in national-level policies to the point in which they can feel it personally, severely, and continuously.

To be sure, I am not saying that as scholars we are immune to the instability and crises which originate at the national level. I am simply expressing that we experience them differently, and that we must recognize this difference so that we can better serve these communities. Within my own project, I became aware that my goals were in direct conflict with what my participants wanted; I wanted to pursue a project which made more salient the struggles of undocumented Filipinx migrants, but given the overarching political crises, increased attention was the last thing they felt they needed. This tension is something all public scholars must navigate, and it is imperative that we make decisions informed by the needs of the communities we serve.

My stance is predicated on an assumption that as public scholars, we do this type of work because we care. And for a great many of us, we care because we are a part of these communities ourselves—the part which has the opportunity, training, and motive to speak out and be heard. But we can’t do our jobs properly if the communities and people we seek to work with disengage out of fear or worry, because even our own experiences are limited by our positionality in academia. We must be cognizant of the very real local- and individual-level impacts of abstract, national policies, and adapt accordingly. We must go the extra distance to make sure that the people we work with understand the value of the type of work we do, and instill in them the confidence of knowing that we will not disrespect them by treating the experiences and stories they give us lightly. Their lives, and the lives of their children, friends, family, and neighbors, can depend on our ability, as scholars and academics, to protect them from any repercussions which might arise from their engagement.

What I’ve said in the context of this paper is far from original, yet it must be reiterated time and again. I must also point out that these are values and ideals that we should always uphold when working with people regardless of the crisis at hand. While it is during these times in which these responsibilities become more conspicuous, we should always be diligent in our work. In doing so, when faced with these precarious situations, we will not approach them as something novel and unfamiliar, because the truth of the matter is that for some of the people we serve, crisis is never really new, it is perpetual.

Alana: The Collision and Intersection of Crises

As part of the MPS Program, I was partnered with a Central Valley county’s food bank, assisting them in assessing gaps in their “emergency food system” in order to “identify populations and areas within the county not receiving/accessing food assistance resources” and “barriers that prevent food-insecure residents from accessing services.”

Initially, I understood that crisis would play a role in the project since a food bank is supposed to provide people with food during a time of intense instability, difficulty, troubles, and insecurity—a crisis. While I suspected that crisis would be central to the project, I did not yet understand the extent to which the food insecurity crisis would be enmeshed in a plethora of other crises for my interviewees, as they experience intense instability and insecurity in multiple aspects of their lives.

As we worked to identify a starting place for the project, the food bank was worried about reaching two populations of interest: immigrant farmworkers and people who are homeless.1 Being a university scholar who was enmeshed in an academic setting concerned with Trump’s rhetoric and executive orders around immigration, I was concerned about the unfolding political crisis and how it would affect immigrant populations’ access to services. I worried how the crisis associated with Trump, that was often discussed within the liberal university setting, would affect food insecurity in the populations I was trying to help. Much attention within the university focused on the claims Trump made in regards to immigration and the effect his inauguration would have on immigrants. Therefore, I was initially surprised when the food bank decided to focus my research on how they could better serve the homeless population. However, working on the project led me to see more clearly how crises can intersect as people’s experiences of homelessness collided with Trump America, in which the president has emboldened neo-Nazis and encouraged police brutality (Beirich and Buchanan 2018; Berman 2017).

As my work progressed, the homeless population’s state of crisis became visible to me, although their crisis was not being widely discussed in the news or the academy. Both food insecurity and homelessness share the key underlying cause of poverty, with homelessness considered to be a severe form of material deprivation (Coleman-Jensen and Steffen 2017). These material deprivations impinge on people’s human rights, as the “Universal Declaration of Human Rights,” Article 25 says:

“Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services, and the right to security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age or other lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond his control.” (UN General Assembly 1948)

The people that I interviewed experienced serious human rights violations as they were deprived of housing and food, and many also faced lack of access to clothing, adequate medical care, and security. This series of serious human rights violations is certainly a crisis given the associated intense instability, difficulty, troubles, insecurity, and danger.

Beyond the experience of the homelessness crisis, the magnitude is incredible, too. The community I worked with had a homelessness rate close to California’s rate of 34 per 10,000 people, which is twice the national rate. California also has the highest rate of unsheltered homeless people in the country at 68% of the homeless population, which was reflected in the absence of a homeless shelter in the town with which I predominantly worked (Henry et al. 2017). The two examples below show how the crisis associated with the current political moment interacts with people’s experiences of the crisis of homelessness.

Civil Discourse, Trump, and Homelessness

When I was interviewing William2 about his experience trying to access food assistance while experiencing homelessness, the multifarious nature of the barriers he faced surfaced. William is a devoted protestor, which has not come without a price. In one instance of doxxing3, he described being targeted by neo-Nazis as retaliation for his activism against Trump. William recalled the retaliation as follows:

“We have a lot of people also down there that don’t like us because of our protests, and they key our vehicle every night. Then, they grab their cell phone, and they do a selfie or have someone else take the picture. And we’ll see the flash, and they’re then posting it on their Facebook page, and their friends look for us. . . . Everybody knows where we’re at because of Facebook and they come on a regular basis all night long. Sometimes I’m awake, sometimes I’m asleep, and you can just hear them, and this is people who say, they put their flag out on the Fourth of July, and say they’re good Americans, but they’re not. There are, there are people who love to hate and I can’t understand that, I don’t.”

William’s account showed how his experience with the current political crisis and homelessness interacted. He felt compelled to protest Trump’s presidency in the face of hatred; however, Trump’s presidency has also led many hate groups to feel empowered, leading to the retaliation that he experienced (Beirich and Buchanan 2018). This retaliation also affected his experience being homeless, as he must carefully pick where to park his vehicle and must sleep lightly each night knowing that violent people are stalking him. When I shared this excerpt with William, he said, “It’s sad that we have to live this way” in the “land of the free, home of the brave.”

Police Brutality and Homelessness

One day, I noticed Raven, one of my former interviewees, walking along the side of the road. Raven is an insightful woman of color, who was struggling with mental health issues and homelessness. She was very invested in the project and would frequently tell me new insights she had on how the food bank’s programs could be improved. We had planned to meet up later that day, so I stopped to confirm our meeting. I learned that she had just been pepper sprayed and left on the street by a police officer. Visibly in pain from the event, she expressed her regret that she was unable to get the officer’s badge number, only his name. I fumbled to assist her, trying to locate more water, a first aid kit, milk, and a restroom.

My academic studies of people in crisis had done little to prepare me to help a person in the moment of experiencing multiple severe crises. In fact, my studies had not prepared me to help a person actually experiencing one crisis. Instead, I had learned how to face the structure that causes crisis, not the actual experience of it. My own response to this emergency was quite clumsy despite the many resources at my disposal, such as a working vehicle, sufficient financial resources, a smartphone, a first aid kit, and my privilege as a white, female graduate student. In contrast, Raven managed to remember the officer’s name and locate a source of water, while travelling by foot, experiencing physical and mental trauma, and navigating the social stigmas of being a homeless women of color.

While I attempted to assist her, I thought: What options does a homeless person have when they are pepper sprayed? How does the crisis of police brutality interact with the homelessness crisis? How were these circumstances extenuated by her being both homeless and a woman of color? While her race, housing situation, and mental health issues likely increased her chances of being pepper sprayed, her housing status also affected her experience leading to and after the incident, and her race and mental health likely could have affected the treatment she received afterwards had she been alone. With no bathroom, car, cash resources, Internet, or medical supplies readily available, she faced very few options for stopping the severe pain on her own.

Reflection

These examples depict just two of the ways the current political crisis affected my interviewees’ experiences with homelessness, and they highlight the importance of considering the multifaceted and simultaneous nature of crises. Public scholars should reflect on their understanding and experience of crisis both within the university and outside of it. Within the university, the crises in the news often seem to dominate discourse, which is an effect of the university’s entrenchment in larger societal systems of oppression. Therefore, I view part of my responsibility as a public scholar is bringing discourse on these less visible crises into the academic narrative. In contrast, I view my role as a public scholar within the community that I work with as one of listening and informed advocacy. Through my engagement with the community, I have learned many lessons on how to confront crises and about how interlocking systems of oppression appear as they are experienced. I hope that I have learned enough from the community in order to effectively contribute to efforts to dismantle these systems of oppression, although I know I still have much to learn. Therefore, I view the role of the public scholar within the communities we work with as a student who is then tasked with using their relative position of power granted to them by the university, as well as any other privileges they may hold, in order to assist the communities in breaking down systems of oppression.

Notes

1 Although these populations are not mutually exclusive, my understanding was that the food bank conceived of these as two different projects, as we discussed how I should narrow the scope of the project.

2 The names of people, the organization, and the site have been changed to protect people’s privacy.

3 According to Merriam-Webster, dox is defined as “to publicly identify or publish private information about (someone) especially as a form of punishment or revenge.”

Conclusion

Our MPS projects took place during a time of national political crisis. Through working with our respective communities, we each came to know the meaning of crisis to our community in different ways. Through our discussions, we saw how the concept of crisis was both relevant and distant to our communities. The continued troubles that vulnerable groups experience in their daily lives differ from the current widespread rhetoric of crisis. We emphasize that these hardships and injustices, which are tied to an unprecedented social inequality, have not erupted suddenly—rather, they have formed over years of structural violence.

As scholars in positions of power and privilege, it is important how we frame the magnitude of the instability and insecurities faced by the communities with whom we work. We must challenge dominant notions of our current “crisis” that ignore the experiences of those in the margins who endure longer, more permanent troubled times, because it is in the act of questioning our preconceived notions that true scholarship emerges.

We hope that through our experiences, readers see how crises can be interpreted subjectively, and can begin to consider how crises may be affecting the communities at the core of public scholarship. As scholars, we must prioritize awareness of the crises facing communities, outside of the framework of academia, in order to better engage with these communities and empower individuals to develop their own solutions and creative forms of resistance.

Future Directions

Mayra: I am still in contact with Estrellitas and will continue to support them with organizing their annual conference. Through my relationship with them, I have been learning how to cultivate close relationships that are supportive, and yet respectful of their time, interests, and processes. I have also learned with them that social transformation takes place in many ways, oftentimes through “small” and slow changes—which are not always visible to or appreciated by us who are part of the fast-paced, metric-oriented, neoliberal university (Mountz et al. 2015). At the same time, I am still reexamining what it means to do public scholarship, and what we define as “community-engagement,” as I continue my work through research projects.

Roy: My work with the undocumented Filipinx community has just begun. More than anything, I am aware of the delicate balance I need to pursue between my goals and what is right for the community as I chart a path forward. My experience is just that—my experience, and I carry with me the understanding that the perspective I put forth in my writing is but one of many, unique in its perspective, but ultimately just a small part of the whole. This opportunity started with the MPS program, but the connections I have made have opened up new avenues for future research and other public work. My positionality as an undocumented Filipinx scholar opens up many possibilities for what I can accomplish, and I hope that through my career I am able to meaningfully serve my community. Moving forward, I will pursue projects that not only add to the conversation regarding the literatures on being undocumented and the API (specifically Filipinx) experience, but also push the boundaries of what can be accomplished with public scholarship in academia and beyond.

Alana: Since completing the MPS program, I continue to work with the food bank and the community that it serves, furthering this project. I aim to work with the food bank to make meaningful changes in their programs in order to reduce the barriers to accessing their services, especially for the most marginalized members of the community. Moving forward in my career, I hope to continue to do engaged scholarship. Studying inequitable food systems, I view it as my responsibility to work with the communities experiencing inequities to dismantle these systems of oppression.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to the communities and organizations we worked with, Dr. Robyn Rodriguez, Dr. Erica Kohl-Arenas, Dr. Rachel Reeves, Davis Humanities Institute, Imagining America, the Mellon Foundation, our faculty partners, and our fellow Mellon Public Scholars.

Work Cited

Beirich, Heidi, and Susy Buchanan. 2018. “2017: The Year in Hate and Extremism.” Intelligence Report, February 11. https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/intelligence-report/2018/2017-year-hate-and-extremism.

Berman, Mark. 2017. “Trump Tells Police Not to Worry About Injuring Suspects During Arrests.” Washington Post, July 28. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/post-nation/wp/2017/07/28/trump-tells-police-not-to-worry-about-injuring-suspects-during-arrests/?utm_term=.d21695c7e14e.

Coleman-Jensen, Alisha, and Barry Steffen. 2017. "Food Insecurity and Housing Insecurity." In Rural Poverty in the United States, edited by Ann R. Tickamyer, Jennifer Sherman, and Jennifer Warlick, 257–298. New York: Columbia University Press.

CONEVAL (Consejo Nacional de Evaluación de la Política de Desarrollo Social). 2015. Índice de Rezago Social 2015: Presentación de Resultados. Accessed May 2016. https://www.coneval.org.mx/coordinacion/entidades/Oaxaca/Paginas/Indice-de-Rezago-Social-2015.aspx.

Henry, Meghan, Rian Watt, Lily Rosenthal, and Azim Shivji (Abt Associates). 2017. The 2017 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development: Office of Community Planning and Development. https://www.hudexchange.info/resources/documents/2017-AHAR-Part-1.pdf.

Jamieson, Amber, Nicola Slawson, and Nadia Khomami. 2017. “Women's March Events Take Place in Washington and Around the World – As It Happened.” Guardian, January 21. https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/live/2017/jan/21/womens-march-on-washington-and-other-anti-trump-protests-around-the-world-live-coverage.

Langholz, Jeff, and Fernando DePaolis. 2015. Economic Contributions of Monterey County Agriculture: Leading the Field through Diversity and Technology. Salinas, CA: Monterey County Agricultural Commissioner. http://montereycfb.com/uploads/Monterey%20County%20Economic%20Contributions%20of%20Ag%202015.pdf.

Marks, Amy R., Kim Harley, Asa Bradman, Katherine Kogut, Dana Boyd Barr, Caroline Johnson, Norma Calderon, and Brenda Eskenazi. 2010. "Organophosphate Pesticide Exposure and Attention in Young Mexican-American Children: The CHAMACOS Study." Environmental Health Perspectives 118 (12): 1768–1774. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/22869.

Merriam-Webster. s.v. "dox." Accessed March 18, 2018. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/dox.

Mountz, Alison, Anne Bonds, Becky Mansfield, Jenna Loyd, Jennifer Hyndman, Margaret Walton-Roberts, Ranu Basu, Risa Whitson, Roberta Hawkins, Trina Hamilton, and Winifred Curran. 2015. “For Slow Scholarship: A Feminist Politics of Resistance through Collective Action in the Neoliberal University.” ACME 14 (4): 1235–1259. https://www.acme-journal.org/index.php/acme/article/view/1058.

Nixon, Rob. 2011. Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Povinelli, Elizabeth A. 2011. Economies of Abandonment: Social Belonging and Endurance in Late Liberalism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Ramakrishnan, Karthick, Jennifer Lee, Taeku Lee, and Janelle Wong. 2017. “National Asian American Survey (NAAS) 2016 Pre-Election Survey.” Riverside, CA: National Asian American Survey.

Shelton, Janie F., Estella M. Geraghty, Daniel J. Tancredi, Lora D. Delwiche, Rebecca J. Schmidt, Beate Ritz, Robin L. Hansen, and Irva Hertz-Picciotto. 2014. "Neurodevelopmental Disorders and Prenatal Residential Proximity to Agricultural Pesticides: The CHARGE Study." Environmental Health Perspectives 122 (10): 1103–1109. https://ehp.niehs.nih.gov/1307044/.

Stein, Rachel, ed. 2004. New Perspectives on Environmental Justice: Gender, Sexuality, and Activism. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Teranishi Robert T., Carola Suárez-Orozco, and Marcelo Suárez-Orozco. 2015. In the Shadows of the Ivory Tower: Undocumented Undergraduates and the Liminal State of Immigration Reform. The UndocuScholar Project, Institute for Immigration, Globalization, and Education, University of California, Los Angeles. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5aa69fbe8f51307aa7d7cdcb/t/5aa6c5718165f57981de21d6/1520878966718/undocuscholarsreport2015.pdf.

UN General Assembly. 1948. “Universal Declaration of Human Rights.” UN General Assembly Resolution 217A. Paris.