Abstract

This essay describes an ongoing collaborative effort between my students and me, during the 2014–2015 school year, to meet with the Latin@ community at OSU, surrounding colleges, businesses, and participants’ homes to conduct interviews that document Latin@ life. The video-narratives collected in this venture are expected to generate a narrative glimpse of Latin@ life in Ohio, as well as a historical record of their presence. The collected stories, narratives, and photographs of cultural artifacts give voice to the different heritages of Latin@s in Ohio.Throughout my academic career, I have looked at ways in which authors of fiction rely on personal and family memory to tell the stories of their characters. Writers like Graciela Limón, Gayle Jones, and Denise Chavez link historical realities into their fiction to force the reader to cross-examine the relationship between literature and their historical past. Each of these writers also allows personal and collective memories to exist as voices that tell their own histories and to exist in parallel to written historical documents. In doing so, novels such as Corregidora by Jones or In Search of Bernabé by Limón allow the reader to consider the realities of people who experienced the historical events alluded to. This is what historical fiction is supposed to do. Gradually, in my teaching and research, I became more interested in the impact storytelling has on the reader. I began to study ethnographies and oral histories and incorporated them into my teaching to heighten my students’ understanding of the communities we were discussing: Latin@s in the United States. I wanted my students to know that we are more than numbers, and that our voices are often dismissed.

I felt overwhelmed about how stories about my community focused on criminality and immigration status, and how these stories left out the voices of those whom they were speaking about. I wanted my students to connect and see Latin@s in their (our) full humanity, even before they ventured out into the community to work alongside their Latin@ neighbors. Furthermore, my desire to provide meaningful experiences to my students by combining research and practical experience led my students and me to begin collecting video-narratives of Latin@s in Ohio in the Spring of 2014, as part of my service-learning class, Spanish in Ohio.

In his seminal book, The Voice of the Past: Oral History, Paul Thompson defends the legitimacy of oral history as a venue that can rescue and bring forth the experiences of marginalized communities by “shifting the focus and opening new areas of inquiry, by challenging some of the assumptions and accepted judgments of historians, by bringing recognition to substantial groups of people who had been ignored” (2000, 8–10). While much of the rhetoric of oral historians revolves around the idea of giving voice to the unheard or uncovering secrets, the oral history project of Latin@s in Ohio discussed here has a broader purpose in mind. This project has collected different life experiences along with cultural and language practices of Latin@ life in Ohio, in order to better understand the ways in which they/we negotiate their/our identities in the United States. Michael Frisch, in A Shared Authority: Essays on the Craft and Meaning of Oral and Public History, contends that history is “A powerful tool for discovering, exploring and evaluating the nature of the process of historical memory—how people make sense of their past, how they connect individual experience and its social context and how the past becomes part of the present, and how people use it to interpret their lives and the world around them” (1990, 188). Indeed, this digital collection invites the listener/viewer to witness the richness and fullness of Latin@ life in the area.

This journey began three years ago. I have recorded firsthand narratives of citizens with a digital video camera to produce a rich historical record of the Latin@/a presence in the state of Ohio. As I interview, and a group of students assists with technical equipment and photography, I am reminded of Alessandro Portelli’s words when he talks about how both interviewee and interviewer—and my students as they hear these first-person narratives—are teachers and students, subjects and objects of study, which I have witnessed during the interviews, and afterwards as my students and I discuss what was said. Portelli says, “Fieldwork is meaningful as the encounter of two subjects who recognize each other as subjects;” furthermore, this exchange is also an opportunity to “stimulate others, as well as ourselves, to a higher degree of self-scrutiny and self-awareness; to help them grow more aware of the relevance and meaning of their culture and knowledge; and to raise the question of the senselessness and the injustice of the inequality between them and us” (1991, 43–44). For example, in June of 2015 I interviewed a group of Mexican American men whose families moved to Lorain, Ohio, in the 1940s. Before I began to interview them, they interviewed me. They asked about my heritage and the purpose of this project. I became the interviewee as they wanted to know details of my personal life and of where I grew up. They asked questions like, “Who are we speaking with? Where are you from? Do you want us to answer in English or Spanish? If you are from that Texas border town, then you know where Hotel Brown is, right?” Some of these men, like me, had lived in Texas and nodded along when I mentioned the East Texas border towns in conversation. Their posture, relaxed demeanor, and jokes suggested to me that I had passed a test. Indeed, we recognized each other as subjects who could begin to work together. This exchange also allowed us to recognize each other as people who shared a history, despite our differences in age, gender, and social status.

The narratives and photos collected are edited and transcribed, and they are now part of the Center for Folklore Studies’ internet collection at the Ohio State University, titled Oral Narratives of Latin@s in Ohio. Participants know that these narratives will be available to the general public and that the collection will provide a unique picture of Latin@s in Ohio that is open to the public and on the web. Because digitizing oral history is becoming more and more common, and in order to take advantage of the many ways we can promote such projects and recruit participants, I created a digital story to give a brief introduction and reflection about the project and what has been collected so far.

Figure 1: Oral Narratives of Latin@s in Ohio. Video by Elena Foulis.

This first video offers an example of the kinds of material we have collected. I recorded this video during a digital storytelling workshop at the Ohio State University in August of 2014. The video is an introduction to the oral history project and my personal connection to it. I have been able to share this video via social media1 and email. It is currently posted on the Center for Folklore Studies’ website, giving the viewer/future participant a “teaser” of the project and, perhaps, a bit more information about who I am and why I am conducting this project. I find that putting my own voice, experience, and purpose in the form of digital storytelling engages the audience and builds community, even before I meet my participants.

In addition to the many ways this collection of life stories can be studied, the presence of the video camera and picture taking during interviews—photography, I notice, is a bigger concern than the video itself—leads to studies on performativity and self-censorship. My participants know, and I remind them, that everything they say will be made public. So they decide how much they want to share. At times, we witness how participants sometimes struggle to overcome the cultural taboos that define them as subjects rather than agents in their own life's events. For example, Latin@s are not a unified group and they live life marked by various levels of bilingualism and monolingualism, Catholicism and Protestantism, blackness, whiteness, indigenousness, and a combination of all of this. Surprisingly, after a few warm-up questions, participants seem to forget about the presence of the camera and a few seem eager to see their videos posted on the internet.

Paula Hamilton and Linda Shopes, in their introduction to Oral History and Public Memories, explain that the scholarship in oral history has been primarily focused on methods and practice, and that there is still relatively little done in terms of publication and interpretations of oral history projects. Perhaps that focus on technique versus content has to do with the very nature of oral history, in which we allow the individual to tell his or her story as a form of data, rather than as a study that addresses the everyday narrative constitution of self-identities. My study pays attention to the discursive acts by allowing participants to engage in different narrative styles to make their experiences real—including memory, argument, advice giving, bilingualism, and the richness of storytelling itself. Emphasizing these different aspects of storytelling provides a particularly ample field for investigation into self-portrayal and self-fashioning of Latin@s. Even more, the venue in which this oral history is being conducted—at a participant's home, work, church, or a neutral location like a hotel’s conference room—leads to the construction of the public image by way of video and photography, which, in some fashion, audio and transcription alone cannot do.

“I love Ohio so much, it’s everything to me. I love this state […] we live in a new world, a transnational world … Ohio has many different nationalities […] it’s the center of the map, it’s América en un estado, yo creo. Yo soy puro Ohio y puro Latino.”

—Carlos Lugo is a Mexican American young Latino who grew up in Akron, OH. At the time of the interview, he was a student at the Ohio State University.

“I would like to give a message to my generation now. I have many friends that don’t understand … I think that they lose themselves. We don’t focus enough on ourselves. One of the main issues with teenagers is that they want to rush to grow up. I know that was me at some point and I think my life went a whole different direction. I want them to spend time with their families … You need that support system. You have to find a family …”

—Selina Pagán was born and raised in Cleveland, OH. She is of Puerto Rican descent and is a student at Cleveland State University.

Both Ms. Pagán and Mr. Lugo, the speakers in these two interviews, are young Latin@s who see themselves as a cultural bridge between members of the majority population and Latin@ millennials who want to educate themselves and keep their heritage alive. In fact, some young Latin@s who grow up in rural areas of Ohio come to learn about the diversity of Ohio heritages once they move to bigger cities to attend college.

Hamilton and Shopes also mention the lack of engagement that has occurred in historical memory in the fields of “history, anthropology, sociology, and cultural studies” and oral history, particularly when, in many societies, history and memory are “inextricably entangled” (2008, vii). They find that little has been done to examine how “oral history, as an established form of actively making memories, both reflects and shapes collective or public memory” (2008, viii). Furthermore, they explain that while historians working in memory studies are interested in the social and cultural practices in many forms (blogging, autobiography, etc.), oral historians privilege the first-person account of participants’ experiences and ignore the process of subjectivity shaped by their cultural and social experiences. Oral historians help elicit answers from their participants that allow those studying a given community, or that allow the interviewee, to reflect on the processes of subjectivity. The more self-reflective interviews are, the more useful they will be for further study by researchers in many fields. Participants in my project have told stories that demonstrate a process of self-creation. Most of the time quite unconsciously, that self-creation is informed by their daily interactions with family, peers, language, and the micro and macro society in which they live. For example, a couple I interviewed talked about moving to Celina, OH, for work. They were agricultural workers who later became interpreters and advocates for migrant workers, as they saw new families moving into the area. In allowing these histories to be revealed, the oral historian (or me in this case) is both the data collector and historical researcher. As such, the oral history of Latin@s in Ohio highlights the presence of Latin@s in the community. Their stories become both data collection and a space that opens up for conversation and understanding of a culture that has shaped the Midwest for generations.

Me: What were some challenges about moving to Ohio?

Participant: Family. I grew up with my tios, tias, primos, I grew up with my grandmother so at various times, there would be an uncle or aunt living there.

I learned to cook, I learned to make tortillas … [when her daughter started school] … I created a slide show of Mexico, Mexicans, and went into schools and spoke about the Mexican culture. I would make tortillas for the kids… . I was just trying to get the word out … I was a Baptist so my church was not real familiar with Hispanics and Mexicans in particular, so I started introducing things. The first time they asked what a taco was, I knew I had my work cut out. So then we started doing things that would encourage education of the Hispanic and Mexican culture….

—Grace Ramos is a Mexican American woman who moved to Dayton, OH, from Iowa in the 1970s.

Me: You mentioned music a lot. As part of your growing up, was there any particular song or songs or stories that you remember from your childhood that are part of you and your family?

Participant: I don’t know like that artist or the particular song but I just remember … I don’t remember the music but for me the music’s always been tied to dance; they’re very intertwined in my family and in Dominican culture as well. You can’t dance without any music, you can’t have music without dancing, so everyone know both, right?

—Ms. Shoenhals is a young professional of Dominican and German descent. She grew up in Mt. Vernon, OH.

Ms. Ramos’s story allows us to understand what life was like for Latin@s in the 1970s. She also reminds us how initiatives to preserve culture and teach others are often deeply personal. Ms. Ramos, and others like her, made it their personal mission to teach others and bring awareness about the limited resources—both in services and goods—available for this growing population. Shoenhals’s story is more personal: her desire to connect to her Dominican culture was influenced by her mother and her frequent trips to the Dominican Republic. Her memories of music and dancing reveal a profound connection to her identity.

When interviewers ask questions and make these interviews available for others to see, the videos expose viewers to different perspectives and personal accounts of how the experiences of these individuals might have or have not been shaped by the macro culture and of how each interviewee was affected by the experience of being a newcomer to relatively small towns in Ohio. In doing so, Michael Frisch explains, oral history “creates its own documents, documents that are by definition explicit dialogues about the past… . The centrality of this project [collecting oral history], I believe, offers some important resources for public presentation and community-based programming” (1990, 188). For example, this oral history has been publicly exhibited digitally online, in an exhibit at the Latino Festival in downtown Columbus, at the Ohio State University, at the Lincoln Library in the west side of Columbus, and at Case Western Reserve University during Hispanic Heritage Month in Cleveland. The iBook version of this project, Latin@ Stories Across Ohio, is being used in my Spanish in Ohio class. Furthermore, the six chapters of the book—“Adaptación,” “Las Activistas,” “Los Profesionales,” “Generaciones,” “Las Fuertes,” and “Los Jovenes”—are grouped by themes which allow readers to choose the topic they want to explore further (Foulis 2015).Documenting Latin@ life in Ohio helps us understand the collective and individual identity of people that have shaped the community they live in and have been shaped by the community, as well. Even more, the breadth of the questions being asked, experiences shared, and languages used allows researchers to investigate further from a variety of fields such as anthropology, linguistics, ethnography, cultural studies, etc.

So Why Document Latin@s?

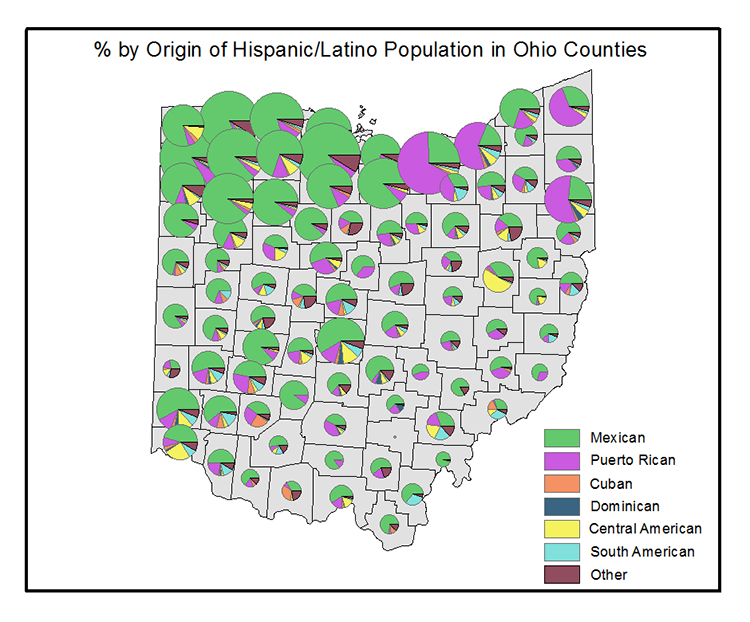

It is important to note the Latin@ population trends and growth that has occurred within the last two decades in the United States. According to the 2010 US Census, the Latin@ population increased by 15.2 million between 2000 and 2010, accounting for over half of the 27.3 million increase in the total population of the United States. Between 2000 and 2010, the Latin@ population grew by 43 percent, which was four times the growth in the total population of 10 percent. The population of Latin@s in Ohio grew 63.4% from 2000 to 2010, and will most likely continue to be the fastest growing group. Ohio exhibits a linguistic and cultural profile of Latin@s unlike that found in other areas with traditionally large Latin@ populations, such as Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, California, New York, and Florida. Although Latin@ presence is often mentioned in the above states, less attention has been paid to the growth of Latin@s in the Midwest, unless of course, one thinks of Chicago.

Oral history in the digital era gives polyphony to a map. It captures the many voices of the community, everyday stories that often go untold. It has the potential to bring attention to those groups that are often negatively or incompletely portrayed in the media.

Latin@s in Ohio are a more diverse population than in other parts of the country, where, for example, Mexican Americans (west of the Mississippi), Puerto Ricans (from Philadelphia to New England), or Cubans (Miami) are the majority groups. There are two large, well-established Spanish-speaking communities in Ohio: the Mexican American population of Toledo, Celina, and other rural areas in the northwest, and the Puerto Rican community of Lorain, Cleveland, and other parts of the industrial northeast. In areas such as Columbus, Dayton, and Cincinnati, meanwhile, we can find a mix of Spanish-speaking heritage of Cuban, Mexican, and Puerto Rican communities. A large number of Central American students, professionals, activists, and other members of the middle and lower classes have given way, in less than a decade, to an even richer cultural heritage that has not been thoroughly documented. The immigration and migration of Latin@s in the state has resulted in culture and language mixing, and sometimes loss. This oral history project documents this moving, shifting, and shaping of an ever-diversifying culture that emerges out of the immigration and migration experience. The sparse scholarship on the languages, cultures, and identities of Latin@s in Ohio makes the digitization of oral history all the more valuable, as this venue can often be visually attractive and quite interactive. The viewer/listener of these rich oral histories can learn that Latin@s are more than restaurant owners or workers, migrant agricultural workers, and part of the industrial labor force. Many of the interviews in this collection demonstrate that Latin@s are fully invested in their community by way of activism, policy making, and cultural events meant to celebrate their heritage.

For example, Lilly Cavanaugh, originally from Costa Rica and now the Ohio Commission of Latin@ Affairs’ executive director, recalls her first years in Ohio and what motivated her to start her first company:

“When starting a company that deals with translation and interpretation, I realized that there was a lot of need for people from other countries. There weren’t many people from Costa Rica but a lot of need for other people, from other countries, and really the people here did not quite understand international people. So I started doing a lot of volunteer work in the community and tried to organize the community, and that was a very good experience too.” (Interviewed in Columbus, Ohio, April 2014).

Similarly, Gabriela Pickett, a Mexican artist living in Dayton, OH, talks about her life as an activist. Her political work is informed by the experiences she had growing up in Mexico and also the experiences she had in Ohio as an advocate for undocumented immigrants.

“It was truly interesting for me. I began to get requests from immigrants [undocumented] to aid them during an emergency. Little by little, we began to help them and more kept coming. Without intending to, I began to speak on their behalf. At first, I felt a little awkward because I felt it was not my place to speak for the undocumented immigrant, especially since I did not share their experience, journeys, and things they had felt. But, if I didn’t do it, who was going to do it? They have no voice, many do not have it, so I decided to do it. I have participated in protests, writing letters, giving speeches, and helping them directly […] [I]t really has been quite satisfying for me because they [undocumented immigrants] have so much to contribute, they have a lot to give to this society, and I hope they get to do it without fear, right?”

—Gabriela Pickett lives in Dayton, OH, and organizes a Dia de Los Muertos parade and celebration each year since 2010. She is an artist and a curator. She is originally from Mexico. She was interviewed in May 2014.

Ms. Pickett’s interview, like our larger oral history project, provides a narrative snapshot of Latin@ life in Ohio, as well as a historical record of Latin@s’ presence. Video oral history has the potential to reach a much wider audience than audio and transcripts, because it is quicker to edit and upload a video onto a website and easy to access. It can also be “carried” in a phone or iPad, linked to an email, or embedded into other sites. Scholars, community leaders, and everyday people can make use of this oral history collection in the future. As Doug Boyd explains in “Achieving the Promise of Oral History in a Digital Age” (2010, 291), when he talks about the demand to digitize oral history, the collected stories, narratives, and photography of cultural artifacts give voice to the different heritages of Latin@s in Ohio and respond to the questions that are being asked of archivists of oral history: “When will your collections be accessible online?” Online collections facilitate users’ searches by categories, and the use of video and photography engage the viewer and encourage connection to what is being said by and about a person or a collective. For example, transcripts alone cannot inform the reader of everything that was said in the interview; body language, pauses, hand motions, and facial expressions are also part of those stories. In the case of pairs or groups, when we watch the video interviews, we witness how participants exchange looks, touch hands, and offer visual comfort when talking about a tender memory. We see how they interrupt each other mid-sentence and finish each other’s thoughts. It is through videos that we witness these interactions and have a more complete picture of, for example, the dynamics of generations, couples, and family storytelling—much of which may be informed by cultural practices.

It is important to note that it is often the oral historian and archivist who are charged with making these materials user friendly and efficient in this digital age. Digitizing oral history increases accessibility in this globalized era. In globalizing the local, we not only add to the understanding of Latin@ identities in the Midwest and across the country, but we also make connections across Latin America, because some Latin@s are immigrants or have family ties abroad. The local collection of Latin@ life informs those who see and hear the stories about the group’s cultural practice and identity, but viewers in this digital era can be from beyond our local and national borders. Digitizing oral history allows for the incorporation of many tools that make the collection more interactive, for example, mapping links to cultural artifacts for further definitions, such as descriptions of cultural artifacts, personal poetry, and music.

This audio is a recording of Yolanda Zepeda’s father. He wrote this song for her mother when he met her for the first time. This audio was included in Zepeda’s video. It is an example of how digital technology allows us to incude participants’ personal pictures, recordings, music, etc.

Figure 8: Audio sample from Yolanda Zepeda. Audio provided by the Zepeda family.

This digital oral history provides a more complete view of Latin@s in Ohio, their historical presence, their involvement in the community, their challenges as a minority group within this Midwest context, and their interest in maintaining their language and culture while also adapting to the new society. Many times, minority groups are not well-represented in the media, or only present a uni-dimensional view. Since the study of Latin@s in the US can no longer be limited to the local, it provides a much-needed conversation about the evolving nature of Latin@/a culture and identity with a transnational perspective. My project pays attention to the role the cultural heritage of individuals and groups plays in how Latin@s negotiate their identities in mainstream US society, and it is a resource for service- and community-based initiatives and opportunities that involve Latin@s in Ohio. But given the diversity of this State, these digital narratives also benefit the general public and community-based organizations by building pride and understanding throughout Ohio’s rich immigrant communities. While it is my intention that this archive will attract researchers in many fields, these video-narratives can also serve as an informational resource for other Latin@s moving to the Midwest, since these interviews cover a wide variety of topics. The visibility of this project, via touring exhibits of the video-narrative and photograph collection and an iBook, titled Latin@ Stories Across Ohio, challenges those that perceive the Midwest as a region with little diversity. This oral history project shows that the Latin@ presence has shaped and influenced the region’s culture, politics, education, and aesthetic landscape.

By the time this essay is published, we will have a new president. Needless to say, the Republican candidate’s position on immigration, immigrants, or in essence, people of color is problematic—not to mention his views on women and Muslims. Not only do his positions open the door to blatant intolerance, discrimination, and aggression; they also threaten to erase the country’s rich immigrant history. The stories of Latin@s, young and old, first, second, and third generation immigrants, and citizens and undocumented people demonstrate human agency and the push for social change. We Latin@s are an integral part of the everyday fabric of life, and not just in terms of being part of the labor force; we are students, teachers, doctors, patients, church leaders, church goers, writers, musicians, artists, entrepreneurs, government officials, mamás, papás, y abuelitos.

Notes

1 There are many video projects out there that look more like a popularity stunt rather than oral history. I am not interested in promoting Latin@ business, or personal agendas. I am, however, interested in providing an alternative version of Latin@ life not always available to our communities. I am interested in providing a historical record of Latin@ life, the adjustment periods, the individual and collective progress of each region of Ohio, their participation in all aspects of life, and the use and loss of the Spanish language.

Work Cited

Boyd, Doug. 2010. “Achieving the Promise of Oral History in a Digital Age.” In The Oxford Handbook of Oral History, edited by Donald A. Ritchie. New York: Oxford University Press.

Foulis, Elena. 2015. Latin@ Stories Across Ohio. Columbus, OH: The Ohio State University. iBook. https://itunes.apple.com/us/book/latin-stories-across-ohio/id1013119968?ls=1&mt=13.

Frisch, Michael. 1990. A Shared Authority: Essays on the Craft and Meaning of Oral and Public History. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Hamilton, Paula, and Linda Shopes, eds. 2008. Oral History and Public Memories. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Portelli, Alessandro. 1991. The Death of Luigi Trastulli and Other Stories: Form and Meaning in Oral History. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Thompson, Paul. 2000. The Voice of the Past: Oral History. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.