Post-World War II Poland existed in a state of divided consciousness. The fettered sovereignty of the state struggling to its feet after the crushing blow of the war was only partly responsible. The most serious problems had their roots in the fact that the Poles found themselves in a land that did not exactly feel like home. The westward shift of the country's territory had landed Poland in a new space.1 Internal migrations changed the face of even places not directly affected by the geopolitical shift. With the exception of Krakow—and even there a vacuum had been created in the heart of the city, in the formerly Jewish quarter of Kazimierz now emptied of almost all Jews—and to some extent also Poznan, to all intents and purposes none of the country's major cities had preserved their pre-war identity. Uprooted from their own small homelands and hastily regrafted in new, "alien" places, people were burdened with a sense of existential impermanence and uncertainty. Their reality had been consumed by the overlapping fields of influence of two mutually neutralizing forces: the heroic effort to rebuild their homeland, and the superficiality of their bonds with the places of which the "new" homeland was composed. For the world of post-war Poland differed significantly from that of the Poland they had hitherto known.

This is why the relationship between history and memory in Poland has specific geographic roots. In the western part of the country, memory veiled history when former German and Jewish inhabitants were displaced by Polish newcomers transplanted from beyond the eastern border of the Polish People's Republic, the Soviet Union—newcomers who, in the new environment, vividly cultivated the memory of places left behind. In contemporary eastern Poland, history buried memory when its official Polish version excluded the differing viewpoints of numerous national minorities and concealed the memory of its former Jewish inhabitants.

Sejny, at the Polish-Lithuanian border, exemplifies such places. In 1990, a group of friends previously connected with the counterculture movement and alternative theater set off on a journey to the east in search of new horizons for their own explorations, to a place where they would be able to combine their creative work with building social bonds and cultural identity. Brought up on the literature of Czesław Miłosz, Jerzy Stempowski, Stanislaw Vincenz, and Jerzy Ficowski, they longed to discover the borderlands that these authors wrote of, vibrant with many languages, to be found, as they repeated after Konwicki, a meter under the ground. Local, multicultural Poland was as nameless to them as a slate wiped clean; they were lured by the promise of discovering and building a new borderland. A meeting with Czesław Miłosz, who was returning to the land of his childhood after half a century in exile, gave them their answer: the place they elected to live and work was Sejny, a small town near the borders of Lithuania, Belarus, and Russia (Kaliningrad). There the four artists—Krzysztof and Małgorzata Czyżewski and Bożena and Wojciech Szroeder—2established the Borderland of Arts, Cultures, Nations Center, one of the most fascinating and significant laboratories of culture operating in Poland since the 1989 watershed. As their base, they chose the abandoned Jewish quarter: the White Synagogue, the former yeshiva, and the old post office, which in time they converted into Borderland House.

The innovativeness and boldness of the Borderland Center's creators lay in the fact that in deciding to settle and work in Sejny, they did not approach the yeshiva and synagogue simply as attractive venues for their own rehearsals and theatrical experiments from which to travel with their productions around the world, from festival to festival. On the contrary, they resolved to transform the imagined world of art into a very real interpersonal space, and to use it as the subject matter, the raw material, of their work. In calling into being this Center of "cultural practices," they were tapping into a train of paradigms with a strong history of presence in Polish culture: the romantic and the positivist (that of organic work), and into the social paradigm so prominent in Polish art: to start making a real impact, and acting instead of merely posing questions. Of greatest significance, however, was their meeting with Czesław Miłosz, who lent his patronage to their plans from the very outset, and whose partnership in dialogue produced the Center's mission: "to create connective tissue for different people living alongside one another" (Jaszewska, 2005, pg. 144).

"We didn't realise how Sejny was hurting, how badly scarred it was by the memory of the conflicts so fresh in the minds of both Poles and Lithuanians [ . . . ]" (Marecki, 2005, pg. 192), Krzysztof Czyżewski recalls about their encounter with the day-to-day life of the town. The bone of contention was the bloody battles of 1919–1920 fought to decide whether the town was to fall within Poland or Lithuania. And while the parties to the conflict were the two nascent states, the battle was fought by the people of Sejny themselves. Essentially it was a war between neighbors, and when the fierce fighting ended, nobody left, everybody stayed put, and life had to go on. But no one forgot who had shot at whom. The subject was avoided—it was not spoken out loud, and no arguments were had, but it was all remembered as if it had happened yesterday. Other tragedies, many of them even less distant in time—World War II is a case in point—had long been consigned to the history books, but the invisible line that bisected the town seventy years previously, in the battles of 1919–1920, continued to divide "yours" from "ours." Only someone who would dare to go deeper into Sejny's everyday life could possibly realize how very much alive that division still was. This was what the founders of Borderland decided to do, even though it meant going to the very seat of the divide. And that required sensitivity, tact, and patience.

An equally important experience was recognizing the "relegation to oblivion" mechanisms. In the 20th century, borders divided not only states but families, and this latter division proved far more profound and resilient than the former. In Sejny and the surrounding area, this meant becoming either a Polish or a Lithuanian family, which must have hurt in a community with such tangled roots. The secrecy, relegation to oblivion, denial, and veiling of entire swathes of family histories had a damaging impact on the lives of both families and the community, and created a second invisible line that for a long time was even harder to cross than the state border.

The Borderland activists questioned the opinion that forgetting is the best way to lay to rest the demons of the past with which Central Europe is so often dogged. There is only one remedy—precisely because for so many years, people in this part of the continent were subjected to "directed forgetting," to no longer keep running from memory. Their memory needed to be detoxified, though this can be very difficult. Remember that when these activists were exploring the situation in Sejny and implementing their first projects there, a bloody drama was being played out in the former Yugoslavia, and there were voices blaming memory for the whole tragedy. Some said it had all been blown up by the constant references to past injury, while at Borderland the focus was more on examining the consequences of directed forgetting and the danger of forced silence ("Ludzie pogranicza," 2000, pg. 2).

The Community's Reawakening

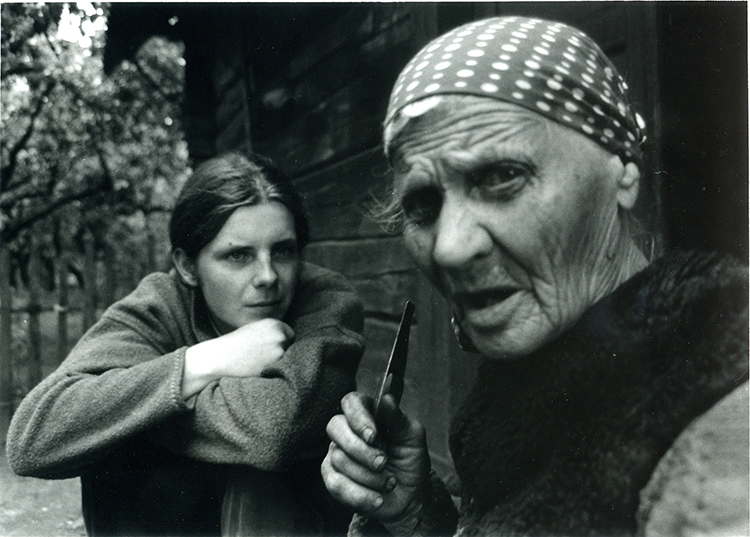

The Center launched its activities with a series of meetings and workshops entitled The Memory of the Old Century. The pivotal element of this project was bringing together young people and their elders. For the first meeting, in the Sejny synagogue, invitations were sent to regional residents of all nationalities and belief systems—Poles, Lithuanians, Ukrainians, Belarusians, Roman Catholics, Greek Catholics, Orthodox, and Old Believers.3 The organizers admitted to being most interested initially in the songs that those gathered would sing, which was what had interested them as artists before they had come to Sejny. They themselves sang Jewish songs to call up those who were no longer in those borderlands—for they were meeting in a synagogue, after all. But in the course of that meeting, as a wonderful atmosphere began to emerge among the people speaking in various different languages all gathered so closely together, emotions came to the fore, and even tears. At the points when the children in the center of the circle carried candles from one group to the next—a theatrical effect involved in that evening—a wonderful silence fell. It was then that the initiators realized that something very special was happening, that they had not expected. These were people who had not sat down together for many years, despite living so close to each other, affected by the same tragic history, but divided by memory, and bereft of the chance to tell each other their experiences.

The drama of that evening is crucial to understanding the further course charted for Borderland's work—the unforgetting made possible through meeting and the experience of its cleansing power thereafter became the foundation for the "practice of memory" cultivated by the Sejny activists.

In time, gatherings of local residents in the White Synagogue, in a circle, with song, grew into a tradition. They happened each year, in late fall, and became called Sejny's "All Souls' Nights." Each such evening was a unique and precious opportunity to awaken a different memory—not a painful memory riddled with wounds and prejudices, which in any case needs no recalling in the borderlands, but a good memory, calling up, at least for a brief moment, the old sense of community. During one of the later evenings the story began to move inexorably towards the tragic moment in the town's history—the internecine Polish-Lithuanian war. The grandson of the Polish mayor from that period told the story of his grandfather, who had grown almost resigned to the constant passing of Sejny from one side to the other, so that he had his pillow and mattress packed and as soon as the Lithuanian troops took the town again, he took himself off to the lockup with his effects. At that, one of the Lithuanians present said that there was a similar story in his own family from those days, of relatives prepared for arrest by the Poles. While these were still painful memories, because they spoke of loved ones who had died from Polish or Lithuanian bullets, they nevertheless also contained a germ of a connection. And stories began to be retrieved from oblivion about shared trading, love and marriages across the divide, joint parties, and so on—stories that are nowhere to be found in the official national canon that hitherto constituted the only information on the attitudes of the two sides (Janowska, 2002, pg. 55). In this way Center activists triggered a process through which, by referring back to this "reawakened" memory, this borderland community began to reclaim its subjectivity.

The generations of those grandparents and parents who had grown up when the nation states were crystallizing, during the two world wars or shortly thereafter, were not eager to forget the wounds inflicted and engage in any sort of accelerated reuniting. The Borderland activists realized very well that it would take time. Top-down methods of managing memory had already been tried, and their efficacy found illusory—hence the importance of not attempting to arbitrarily supplant "bad" memory with "good." They therefore decided to work with the young residents of this borderland region, and to propagate among those they worked with an attitude of respect for these painful memories.

The young people could make use of the experiences gleaned from talking to their elders in creating stage plays or films. One such was the production The Sejny Chronicles, whose script was written by the young people themselves. To do so they dug into their families' archives, and asked questions of their grandparents. And they discovered a world of which they had had no inkling. It suddenly transpired that they had a Lithuanian aunt, or a Jewish grandmother, information that had been kept secret for years. They learned how their grandfather had died at his own neighbor's hands, or how a Jewish child had been taken into hiding in their house during World War II. These stories were vastly important to the older people, too—who for years had not been listened to, had had no one to tell of the things that lay heavy on their minds. These were secrets of a deeply personal, existential nature, and at last the burden was being lifted. It was easier to bare their souls to their own grandchildren. The young people, in turn, through their work on their play or film, exhibition or book, could repay their debt to their elders and take their stories forward, creating a revived history for their town and region.

Borderland has created a community of memory in Sejny. The White Synagogue has become a space for cultivating a common memory drawing on the entirety of the multicultural heritage of these borderlands. The Borderland team even came to speak of a "new public ritual of community" (Janowska, 2002, pg. 55), a forum for intercultural and intergenerational communication.

The focus of Borderland Center activities is using cultural practices to try and formulate principles around which to build the nascent culture of remembering. They do not consider the contemporary renaissance of memory a typical phenomenon for societies freeing themselves from forced not-remembering, as the Poles—or, more broadly, the Central Europeans—currently are doing. Even in the West, "memory was buried in the darkest recesses of the soul and the earth" (Czyżewski, 2005, pg. 228) in an attempt to overcome the trauma of World War II. It was then overlaid by a layer of post-war protection that grew up with the increasing prosperity of the consumer society. This, in turn, gave rise to political correctness, which shied away from awkward questions and deeper penetration in the sphere of interpersonal relations. In the communist East, the counterpart to political correctness was state censorship, which stood guard over its monopoly on ideology; this, in turn, distorted the past and turned remembering into a dangerous, closely policed zone. On both sides, a range of forms of not-remembering was practised, largely precluding the chance to cultivate anywhere in post-war Europe a culture of memory that might act as a catalyst for the tragic experiences of the people in this part of the world throughout last century (Czyżewski, 2005, pg. 228). Europe—a continent that lives through its history like no other—could not last in that state for very long. The collapse of the Berlin Wall, the war in the former Yugoslavia, the new nation states, and the population migrations all released memory, which forced its way onto the arena of public life. Aside from the festering wounds, another source of this renaissance of memory was the "authentic need for a contemporary Odysseus, toiling to return home" (Czyżewski, 2005, pg. 228), as Krzysztof Czyżewski metaphorically expressed the condition of post-modern humanity, evoking a lesson learned from reading Simone Weil.4

Yet today, memory is widely used as a weapon in the "war of cultures" that is being waged between societies. For societies, too, are subject to the rules of the market game, and compete for position and influence. Culture offers great potential in this respect—skilfully wielded, it can touch up one's image, promote, compete, attract tourists . . . Naturally, success also depends on financial resources and market position. This means there is a marked disproportion between the handful of people authentically engaged in honest, profound reflection on the past and the army of scholars, museum workers, managers, directors, writers, and journalists—who are known at Borderland as "memory stylists"—trained and employed in the festival and exhibitions industry and in memory-based institutions. Their efforts, in spite of the grand scale of their activities, may affect superficially. What is even worse, warn Sejny's activists, they easily form a symbiotic relationship with populism and the market. From there they are only a step from feeding resentments and superiority or inferiority complexes, so activating the "war of differing memories" (Czyżewski, 2005, pg. 229).

The culture of remembering the Borderland Center is devising is about less spectacular work. The issues of border regions, including memory, are, as real problems, neither pleasant nor able to guarantee media-worthy success. The Center therefore offers "a cultural archaeology of memory," deliberately accenting the importance of tireless, low-level hard work. The place of artists and scholars seeking to satisfy their own vanity with public applause is taken by "memory workers" who, like archaeologists, uncover scraps of memory, deciphering forgotten names, effaced symbols, discarded traditions. Through their work they familiarize the place and discover that they are not alone there, but share it with people of other ethnicities. There are also those of whom but traces remain, for whose preservation these "memory workers" alone take responsibility. Krzysztof Czyżewski wrote,

It is in this way, locally, in respect of a specific Place and people, in the daily practice of 'geography of Place' that a culture of remembering is developed, building social bonds and cultural identity, but also inspiring exploration and new forms of artistic expression. (Czyżewski, 2005, pg. 229)

This context of place and memory calls to mind Pierre Nora's notion of realms of memory (lieux de mémoire). Where did realms of memory come from? Nora says that our times are marked by a sense that memory has been shattered, and by the awareness that communication with the past (via memory) has been interrupted. In such conditions we start to seek out realms where memory crystallizes and takes refuge. It is only this embodiment of memory that gives us a sense of historical continuity. Lieux de mémoire—realms of memory—exist, Nora posited, because there are no longer milieux de mémoire, true environments of memory, environments in which memory is an authentic part of the everyday experience (Nora, 2009, pg. 6–12; Judt, 2011, pg. 232–258).5 He was prompted into this mode of thought by his observance of the demise of rural culture in France; from today's perspective we might add also the decline of industrial civilization. The France of his day was modernizing and at once, as he saw it, shrinking and dividing. What had once been day-to-day life was rapidly becoming the realm of history; the present was receding into the past, and any moment, Nora predicted, nothing more would remain of the former myths and glory (Judt, 2011, pg. 240).

Do True Environments of Memory Exist?

At the same time that Nora proclaimed his lieux de mémoire, though at the other end of the continent and unbeknown to him, given that the divide was still sanctioned by the iron curtain, a small group of young people had just founded an alternative theater in the village of Gardzienice near Lublin. Before Borderland, its founders, Małgorzata and Krzysztof Czyżewski, were two of the members of that theater, which formulated an innovative program seeking a "new natural environment for the theater," born out of—or rather in defiance of—a similar fear, the death of tradition.

The basic elements of the artistic work of Gardzienice were Expeditions and Gatherings (Machul, 2001, pg. 366–379). Aside from trips to other villages and exploration of the traditional culture still vibrant there, these Expeditions also incorporated a performance and a Gathering. Central to this concept is mutuality, one of the key notions at Gardzienice: the group offers its performance, and in exchange receives songs, gestures, stories, and traces of ritual. The time for expression of this mutuality was the Gathering, a means of meeting people devised by the group, usually as the culmination of an Expedition, but also potentially independent. In every case the genesis of the Gathering was spontaneous—it came after the performance, when the audience had stayed behind, still talking, and after a while singing would begin. Song was at the heart of the Gathering, its "nerve." Zbigniew Taranienko, one of the participants in the Gatherings, has some interesting observations:

The songs that called them [the Gatherings] to life, interspersed with performances of the group's etudes and by music performed by its members and those invited, by colourful tales and often by joint dances, provoked in the people who came to the meetings reactions not released on a day-to-day basis, brought out concealed emotions, revealed profound experiences. Gatherings held in larger venues—in fire brigade or school halls—were often attended by whole villages, from small children, through young people of both sexes and adults, to old women and old men. Sometimes old animosities between them came to the fore, or festering wounds opened up. But they came together in song, which bound up these scenes of the natural 'theatre of life' not expected by anyone into a single whole. (Taranienko, 1997, pg. 96)

A comparison of the "All Souls' Nights" celebrated in Sejny synagogue with the Gatherings practiced by the Gardzienice theatre group reveals many analogies. Most important is probably that bringing people together to an appointed place, and the dramatic effect involved in such an act, is a successful way to "reveal, or project, the truth in the cultural, human existence of a community" ("Rozmowa z Włodzimierzem Staniewskim," 1986, pg. 134–136).

The parallel between the work of Borderland and Gardzienice6—at least in the initial years of the Sejny Center's work as their original method was developing—is essentially self-explanatory. Perhaps less evident is another comparison—between Krzysztof Czyżewski's words in the context of the "All Souls' Nights" and Pierre Nora's inquiries. Both spoke of "awakening memory," but the way they understood this is only apparently similar. Czyżewski spoke of "good" and "bad" memory and of the need to confront these as a condition of the community regaining its subjectivity. Nora was speaking in the context of "decolonialization" and the release of many stifled memories after 1989, yet he registered only the pluralism that memory brings to history, while in fact he was actively opposed to redefinition of history, which could lead to the disintegration of France's national canon. The memory for which Nora expresses his concern is charged with serving the nation and its historically petrified cultural universum. The Borderland Center's concern, on the other hand, is with memory's role in fostering redefinition of the community, and thus also—and even primarily—the nation, but not subservience to it.

Borderland's activists have secured access to something that had prematurely been pronounced extinct. The culture of remembering developed by the Center has confirmed that it is possible to "go deeper," to reach the stream of enduring of which Bergson wrote, the durée7 that is the true repository of the past.

A Laboratory for Modern Culture

The Borderland team have created one of the most original programs for working with history and memory in a specific place and community, and its results and significance go far beyond the local context. Today the Borderland is one of the most important cultural laboratories whose methods and philosophy offer an inspiration and model for other such initiatives all over the world. It was artists who took on responsibility for the community in which they decided to live, and became its activists. They made the extra effort to universalize the experience granted them by their work in Sejny, and created a model for a contemporary "culture of remembering" reinforced by practice.

In the former yeshiva, Czyżewski and his group formed workshops for young people, the primary ones being The Sejny Chronicles, in which three "generations" of students have learned about the past of the town and the memory of its inhabitants, in order to create a theatrical or film story about the former multicultural Sejny, or a historical game that tells about the culture and everyday life of the borderland; and The Klemzer Orchestra of the Sejny Theater, in which three "generations" of young musicians have brought forgotten musical traditions back to life, and who now create music with the most celebrated representatives of the American klezmer revival. (See, for example, The Musicians Raft SejNY). At the heart of the Borderland activities, however, are not only shows and concerts (although these have been presented from the Caucasus to America), but also a re-established community of memory, thanks to everyday work. The White Synagogue has become a space of cultivating this community; there this community finds its expression and an intercultural and intergenerational transfer can be realized.

Thus the once-abandoned Jewish quarter—in the very heart of town—is today revived and considered the "agora of Sejny." The Borderland complex is comprised of three buildings: the White Synagogue, the former yeshiva, and the House of the Borderland, with the exhibition about the former multicultural Sejny as well as the Documentation Center of Borderland Cultures, a library and media center whose collections include materials on almost all "sensitive" borderlands, not only those in Europe.

The Borderland Center's mission is not limited to Sejny. Thanks to the Borderland's publishing house, ideas reach further. Especially deserving of attention are the two series edited by Krzysztof Czyżewski. Meridian showcases the poetry, prose, and essays of many authors from East and Central Europe, such as Mihail Sebastian, Josif Burg, Grigorij Kanowicz, David Albahari, Max Blecher, Norman Manea, David Filip, Gordana Kuić, Mordechaj Arieli, Elias Canetti, and Hannah Arendt. Neighbors began in 2000 with Jan Tomasz Gross's book Neighbors: The Destruction of the Jewish Community in Jedwabne, Poland, which describes the tragedy of 1600 Jews in Jedwabne murdered on July 10, 1941 by their Polish neighbors. This publication prompted an important debate in Poland concerning memory and responsibility after the end of the World War II. Today it is impossible to overestimate the importance of the publishing house's decision for the revision and transformation of the Polish memory of the twentieth century.

The ideas, attitudes, and cultural practices developed by Krzysztof Czyżewski are organized into an original philosophy of the "culture of remembering." In 2014, he was honored with the Dan David Prize for his special contribution in understanding the relations between history and memory, and between contemporary perception and narratives touching the past.

With reference to Nora's realms of memory—and Pierre Nora has been recognised with the same prize as Czyżewski— Sejny has been enriched with a dialogic, super-national dimension, by proposing a more capacious and arguably more contemporary version: realm of common memory. But if we accept, after Nora, that contemporary culture has only artifices of memory available to it, the Borderland Center has an important alternative to offer: the determined attempt to lift the spell on the natural environment of memory—for that is at the heart of the "unforgetting" and the culture of remembering practised in Sejny.

Notes

1 As agreed by the Allies during the Yalta Conference held 4–11 February 1945, the Soviet Union incorporated the lands in eastern Poland (the so-called Kresy, east of the Curzon Line), previously occupied and annexed in 1939. The Allies compensated new Poland with the German territories east of the Oder–Neisse line, parts of Pomerania, Silesia, and East Prussia (the so called Recovered Territories). The entire country thus shifted to the west and resembled the territory of Medieval Poland. Per the Potsdam Conference (17 July–2 August 1945) agreement, several million Germans were forced to relocate to the new Germany. The new western and northern territories of Poland were repopulated with Poles "repatriated" from the eastern regions now in the Soviet Union (2–3 million people). The population transfers included also the moving of the Ukrainians and Belarusians from Poland into their respective Soviet republics. Still the thousands of Ukrainians stayed so in 1947. They were expelled by communist authorities to the Recovered Territories during the Operation Vistula. They were forced to leave the south of Poland, their homeland, and move to the north-east, north-west, and south-west of the country. Adding the Holocaust consequences – emptying up cities, towns, and villages where Poles and Jews used to live together, the post-war Poland differed significantly from the country it used to be.

2 See http://pogranicze.sejny.pl/centre,128.html (accessed 25 February 2015).

3 The Old Believers, also known as Old Ritualists, separated after 1666 from the official Russian Orthodox Church as a protest against church reforms introduced by Patriarch Nikon between 1652 and 1666. Old Believers continue liturgical practices that the Russian Orthodox Church maintained before the implementation of these reforms. In the aftermath of the schism, persecutions began and many Old Believers fled Russia altogether. Many of them took their refuge in the north-east of Poland, e.g., in the Sejny region, where they still live.

4 Particularly the "uprootedness," which Weil diagnosed in The Need for Roots: Prelude Towards a Declaration of Duties Towards Mankind.

5 See also Tony Judt's comments on Nora's conceptions in his essay, "À la recherche du temps perdu: Francja i jej przeszłości." The essay was a review of the three-volume American selection of the works of Nora published as Realms of Memory. The Construction of the French Past by Columbia University Press in the years 1996–1998. Judt's review was printed in The New York Review of Books on 3 December 1998.

6 In 1983, Krzysztof Czyżewski and Małgorzata Sporek-Czyżewska left Gardzienice. They wanted to look for their own answer to Jerzy Grotowski's demand of abandoning the theater and connecting with real tissue of interpersonal relations. The split with Gardzienice was accompanied by their strong feeling that the counterculture movement they were part of was becoming more and more artificial. In the mid1980s, the Czyżewskis met the Szroeders and started to act together. They organized meetings called Wioski Spotkania: Międzyanrodowe Warsztaty Kultury Altrnatywnej (The Village of Encounter: An International Workshop for Alternative Culture) held every summer. They transformed the last workshop, in 1989, into the journey, named after Hermann Hesse's novel, Journey to the East. It lasted a few months and led them to Sejny where they settled down and established the Borderland Center.

7 Namely the inner life of man, which in Henri Bergson's notion is a kind of duration, neither a unity nor a quantitative multiplicity. Durée is ineffable and can only be shown indirectly through images that can never reveal a complete picture. It can only be grasped through a simple intuition of the imagination. That is why Borderland's activists rely on drama and art in their work with the community.

Work Cited

Czyżewski, Krzysztof. 2005. "Powrót do Miejsca. Zamiast posłowia" ("A Return to the Place. Instead of an Epilogue"), in Warto zapytać o kulturę (It's Worth Asking About Culture). ed. Krzysztof Czyżewski. Białystok–Sejny: Pogranicze.

Jaszewska, Maja. 2005. "Opowiedzieć mit pogranicza" ("Telling the Myth of the Borderland"), in Przegląd Powszechny.

Judt, Tony. 2011. ("À la Recherche du Temps Perdu: France and its Pasts"), in his Zapomniany wiek dwudziesty, (Forgotten Twentieth Century). transl. Paweł Marczewski. Warszawa: WUW.

"Ludzie pogranicza" ("People of the Borderland"), 2000. Tygodnik Powszechny. December 10.

Machul, Piotr. 2001. "Mały słownik terminów Ośrodka Praktyk Teatralnych 'Gardzienice'" ("The Little Dictionary of Key Notions of the Center for Theater Practices Gardzienice"), Konteksty. Polska Sztuka Ludowa, 1–4.

Marecki, Piotr. 2005. "Miejsce pisane z dużej litery," in Pospolite ruszenie. Czasopisma literackie w Polsce po 1989 roku (Kraków: Ha!art).

Nora, Pierre. 2009. "Między Pamięcią i historią: 'Les lieux de Mémoire'," Tytuł roboczy: Archiwum /Working title: Archive 2: 6–12.

"Rozmowa z Włodzimierzem Staniewskim." 1986. Pismo, 3: 134–136.

Taranienko, Zbigniew. 1997. Gardzienice. Praktyki teatralne Włodzimierza Staniewskiego (Gardzienice. The Theater Practices of Włodzimierz Staniewski). Lublin: Test.